When Willem Dafoe was a little boy in Appleton, Wisconsin, he shut himself in a closet for two days. Nobody missed him. "It was a big family. My dad was a surgeon, my mom a nurse, and they were always out working. I had five sisters and a brother. They didn't care what I got up to."

Maybe – and it's a theory that would get me evicted from Freudian analysis 101 – the abandoned boy became the inveterate pleaser of adults. Perhaps that early experience of neglect explains why Dafoe has so often been an obliging actor, ready to do anything to accommodate a director's fruity demands. Think Lars von Trier directing Charlotte Gainsbourg to crush his testicles with a block of wood in Antichrist; Madonna, playing a dominatrix, pouring hot wax over his naked body in Body of Evidence ("Not there," said his eloquent grimace. "Anywhere but there!"); David Lynch insisting he wear discoloured, deformed dentures to look more satanic in Wild at Heart; skinning a wallaby in preparation for his role in The Hunter; graduating from Oliver Stone's boot camp to be buff enough to play a Vietnam GI in Platoon; the endearingly weird stage stuff he does with director Robert Wilson (of which more later); and not to mention his TV voiceover as Clarence, the Birds Eye polar bear.

He's nothing if not game, I suggest. "Yes, I am game. I've always been game – maybe to a fault." He tells me of the time in 1995 when the photographer Anton Corbijn, who recently directed him in A Most Wanted Man, took his picture in New York's SoHo. "We walked from the theatre and he found this texture in the wall he liked. He said would you take off your shirt. So I did."

Typical Dafoe: he gets his kit off without compunction, and more besides if he likes where the artist is coming from. Why does he put out so much? "When I give over to somebody's vision rather than have an idea of what I need to do, it takes me to places I wouldn't have got to by myself. I'm always attracted to a strong director." How different from the narcissistic monsters many actors become. "Everybody's different," says Dafoe. "But sure, actors trip themselves up where professionalism is a certain kind of method or approach that they become slave to. A lot of actors get into this profession to be king of the world. I don't want to be king of the world.

"For me the thing is not to have expectations and let them harden. The best thing an actor can be is ready. Be flexible, be ready." Not a bad mantra for a 57-year-old to have.

Did the boy in the closet grow up into the man who would do anything not to feel so neglected again? Apparently not. When Dafoe was locked in that dark closet, he wasn't so much neglected as mastering himself. Manned space flight was a new thing and little Willem, like a pint-sized wannabe Major Tom, wanted to know if he had the right stuff to remain in a confined space for a long time. So he opened the wardrobe door and disappeared into his own private Narnia.

"When I was a kid I was very interested in the idea of the will, finding out what you're capable of. I liked those kind of challenges." Like holding your breath underwater? "Kind of," laughs Dafoe. "But I was more like G Gordon Liddy eating a rat." Eating a what? It turns out that Liddy, the FBI agent jailed over the Watergate burglaries, is notorious for roasting a rat and eating it to overcome his rodent fear as a child.

He's eaten a rat, has he? "Close. I've done lot of things in my time." Dafoe's voice isn't quite as comically sinister as the one with which he ventriloquised the cider-addled, blade-wielding Rat in The Fantastic Mr Fox, but not far off. Hold on. What is close to eating a rat? Did he barbecue and eat that skinned wallaby? "Let's not get into that now."

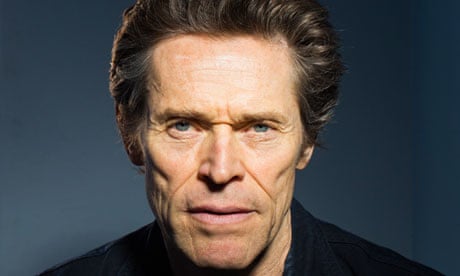

We're sitting in a sunny room in the Teatro Nuovo in the Umbrian hill town of Spoleto. Outside, English tour groups are setting off on archaeological excursions and the sun-drenched, verdant hills are unremittingly gorgeous. Inside, Dafoe is sitting across the table in a grey round-neck sweater and drainpipe jeans, staring deep into my eyes at very close quarters. I'm confronted with the face that years ago the Village Voice described as the "pallidly beautiful embodiment of pure evil". Personally, I'd kill for hair as lush as Dafoe's in my sixth decade or to have a face so craggily characterful. In any case, that pallid beauty was harnessed by Martin Scorsese for one of Dafoe's most memorable film roles, the title part in The Last Temptation of Christ – and Jesus was, unless I've misunderstood the Bible horribly, never an embodiment of pure evil.

Dafoe is in Spoleto for a rehearsal with one of those strong directors to whom he loves to abandon himself. He and the dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov are working with Robert Wilson on a stage version of a lovely absurdist short story, The Old Woman, by cult Soviet surrealist writer Danil Kharms, which they will premiere at the Manchester international festival next month and then bring back to Spoleto.

When he was sent the script for The Old Woman, radically adapted by American writer Darryl Pinckney, Dafoe noticed that there was no role for the old woman: just two characters, A and B. "So I called Bob and said: 'Is Misha A and I B?' He said: 'I don't know.' So I learned both parts. I only found out later which I was playing."

Is it always like that with Wilson? "Bob's a very strong personality and has a strong aesthetic and you submit to his vision. His theatre is not burdened with personality or manner or psychology. That's the kind of engagement I like. Because when your plate is very full, not with ideas but with tasks, that's when you perform in a purer way. It's like animal instinct. When I feel my most free and have my greatest discoveries is when the world drops away and my attention is based totally on action and balancing and sound, light and music. It's very difficult work."

I'm reminded of what DH Lawrence wrote in a poem: "There is no point in work/Unless it absorbs you/Like an absorbing game." This, no doubt, is what Dafoe gets, at best, from working with Wilson. But doesn't he abandon his will, ego, perhaps even his dignity, as he submits to Wilson's vision? "I do, but I like that. You have to lose yourself to find yourself." He nods at his yoga gear on the table. "That's why I'm a yoga practitioner too."

To try to get a sense of what Dafoe is on about I ask to sit in on a rehearsal but I'm told that won't be possible. Instead, I'm ushered into an editing suite in the theatre with Dafoe's Italian wife, the film-maker and actor Giada Colagrande. He married Colagrande in 2005, a year after splitting up from his long-time partner, theatre director Elizabeth LeComte, with whom he has a grownup son. He now has dual Italian and American citizenship and divides his time between Rome, New York and LA.

Colagrande shows me footage of Dafoe and Baryshnikov rehearsing. I'm not sure which is A or B, but both men perform like a hysterical double act, wearing wigs crimped like swirling ice-creams, and lurid makeup, including painted-on glasses. "He couldn't speak because he lacked a mouth," shouts Dafoe in falsetto. "His arms and legs? He didn't have any. No intestines. He didn't have anything … " In another scene the two actors are sitting like acrobats on a swing – as pert, poised and potty as Gilbert and George, if more gaudily attired. Gestures and expressions are precisely choreographed. I can now see why Dafoe likes this kind of work. There's so much to do, to concentrate on, to lose oneself in. It must be a relief from being in the boring real world. And yet what does it all mean? Dafoe is no help. "It is what it is," he says. "Not something else. Things are more beautiful that way. You aren't pointing at things. I feel more comfortable in this world of physical theatre than anywhere else."

He says he has felt that way ever since he got into theatre. He was thrown out of Appleton high school for making a pornographic film ("It wasn't really pornographic. It was just a film about oddballs, including nudists") and later dropped out of drama school at the University of Wisconsin to join the first of a series of experimental, physical theatre troupes. In 1976 he arrived in New York, where he helped found the Wooster Group. "I was with the Wooster Group for 26 years because it's in that kind of physical theatre that I find my pleasures. In the poetry of things rather than interpreting things."

Two years ago, Dafoe went to Manchester to perform as the narrator in another wild Wilson play, The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic, about and starring the godmother of performance art. Alfred Hickling, reviewing the show for the Guardian, wrote that Dafoe's performance in orange mullet and heavy pan-stick makeup "puts you in mind of Batman's the Joker MC-ing a Berlin cabaret".

It intrigues me that Dafoe appeared in this play since Abramovic surely represents the antithesis of the theatre he likes, one in which everything is defiantly artificial. Abramovic, who became famous anew in 2010 with the 700-hour silent performance The Artist Is Present, for which people queued overnight for a one-to-one encounter with her in the lobby of New York's Museum of Modern Art, once rounded on theatre's artificiality. "The knife is not real, the blood is not real, and the emotions are not real. Performance is just the opposite: the knife is real, the blood is real, and the emotions are real."

Isn't she right? Theatre people are phonies, never really present. "I know Marina well and I have these conversations with her all the time," retorts Dafoe. "In performance art you can get sidetracked by the personality, the risk and the pain, and you can miss the art and poetry of it." Not a bad argument, especially if you consider what happened when Abramovic lay inside a flaming star made of petrol-soaked sawdust for a performance. The fire sucked the oxygen from around her, she passed out and wound up in hospital with burns to head and body. In Wilson's theatre, Dafoe argues, there's little risk of distraction from purely aesthetic, formal moves. "It's through the artificial that you get to what's real."

That said, Dafoe has also found space on his CV for hokum that can't be justified with such aesthetic high-mindedness. He's been in his share of Mr Beans and Spider-Mans, and was nominated at the Golden Raspberries in 1997 as worst supporting actor for his performance as the baddie in Speed 2: Cruise Control. But arguably the worst performance he ever gave was in his first film, Heaven's Gate, for which he was cast in a minor role. He was standing on a silent set and a woman whispered a joke into his ear. He laughed out loud and director Michael Cimino said: "Willem step out."

It's hard to believe a great director would dismiss Dafoe so precipitately now. He's too valuably weird a presence, always ready, always flexible – no wonder he's been sought out recently by Wes Anderson (for The Grand Budapest Hotel). He also cultivates those directors he likes to work with. One day, he wondered how his old chum Von Trier, with whom he had worked on Manderlay, was doing, so he called him up. "I'm terribly depressed," Dafoe reports the gloomy Dane saying. "I've written a screenplay and I don't know if it's any good. Would you look at it?" Dafoe read the Antichrist and wanted to play the role of the husband in a grief-stricken couple whose toddler son plunges to his death while they are having sex in another room. Why didn't he read the script and go: "This is too harrowing! [Spoiler alert!] He gets castrated. She performs a clitordectomy on herself. Then he strangles her and burns her corpse. No way!"

"I thought there are interesting things to do for an actor and there were some things I wasn't clear about what they meant," Dafoe says. "But I'm often not clear what stuff means."

No matter. He has just finished working with Von Trier again on a film called Nymphomaniac, to be released later this year, in which Gainsbourg plays the eponymous lead. Should feyer cinemagoers prepare their smelling salts? "There are a couple of scenes with Charlotte and that's all I want to say. There isn't anything to say, except that it's not as expansive a role for me."

We wander around the bowels of the theatre. Each of the Teatro Nuovo's many boxes seems to have a cell-like room behind it. My guess is they were originally designed to facilitate private slap and tickle for bored theatre-goers. Today the photographer asks Dafoe to sit inside one. The room is tiny, reminding me of Dafoe's childhood closet.

"I'm still doing now what I did then," says Dafoe when I point this out. "I set myself challenges every time I work. Ideally I approach everything as though it's the first time – with a beginner's mind and an amateur's love."

Thesps – you've got to love them. Can anyone else get away with this stuff? Dafoe stares at me hard. "Don't make this into a crackpot profile, please. That's happened before." He's got previous with the British press. "Who's that awful woman?" he asks. Lynn Barber, probably. "That's her! I think she thought I lived by the pool with all these flunkies and her life is very hard so she wanted to portray me as this useless bugger."

My esteemed colleague Simon Hattenstone asked Dafoe if the rumours were true that he had Hollywood's biggest penis. Does he? Dafoe laughs obligingly, before heading off to rehearsal. "I don't really work in Hollywood any more." Which, you'll notice, isn't a denial.

The premiere of The Old Woman is at the Manchester International Festival on 4 July, www.mif.co.uk

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion