Abstract

The terms ‘natural rate’ and ‘market rate’ of interest were introduced by Wicksell (1898, 1906) to denote an equilibrium value and the actual value of the real rate of interest. Wicksell applied these concepts to explain the inter-equilibrium movement of money and prices using the hypothesis of maladjustments in the interest rate. Wicksell’s work made the nexus between money creation, intertemporal resource allocation disequilibrium and movements in money income the dominant theme in macroeconomics for three decades. However, Keynes’s conclusions over the saving–investment problem in the General Theory led to the abandonment of the concept of ‘natural’ rate of interest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Credit

- Cumulative processes

- Fiat money

- Forced saving

- Hayek, F. A. von

- Inflation

- Inflation targeting

- Inside money

- Intertemporal resource allocation

- IS–LM model

- Keynes, J. M.

- Liquidity preference

- Loanable funds

- Monetarism

- Money supply

- National income

- Natural rate and market rate of interest

- Neutrality of money

- New classical macroeconomics

- Overinvestment

- Quantity theory of money

- Saving–investment coordination

- Stockholm School

- Unemployment equilibrium

- Wage rigidity

- Wicksell, J. G. K.

JEL Classifications

The main analytical elements of Knut Wicksell’s Interest and Prices can be found in the works of earlier writers. Wicksell was familiar with Ricardo’s distinction between the direct and indirect transmission of monetary impulses. Although unknown to Wicksell in 1898, Henry Thornton had provided a clear account of the cumulative process in 1802, as had Thomas Joplin of the saving–investment analysis somewhat later (cf. Humphrey 1986).

Yet Wicksell did not just coin the terms ‘natural rate’ and ‘market rate of interest’. His development (1898; 1906) of these ideas made the nexus between money creation, intertemporal resource allocation disequilibrium and movements in money income the dominant theme in macroeconomics for three decades until it was submerged in Keynesian economics. His starting point was the quantity theory, understood as the proposition that in the long run the price level will tend to be proportional to the money stock. His objective was to explain how both money and prices come to move from one equilibrium level to another. This inter-equilibrium movement became his famous ‘cumulative process’. The maladjustment of the interest rate was the key hypothesis in Wicksell’s explanation.

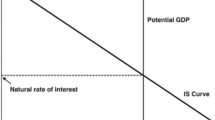

The ‘market rate’ denotes the actual value of the real rate of interest while the ‘natural rate’ refers to an equilibrium value of the same variable. The latter term by itself divulges Wicksell’s engagement in the ancient quest for a ‘neutral’ monetary system, that is, a system neutral in the original sense that all relative prices develop as they would in a hypothetical world without paper money. Wicksell asserted three equilibrium conditions that the interest rate should satisfy; the first of these was that the market rate should equal the rate that would prevail if capital goods were lent and borrowed in kind (in natura). This criterion was later shown by Myrdal, Sraffa and others not to have an unambiguous meaning outside the single input–single output world of Wicksell’s example. The further development of Wicksellian theory, therefore, centred around the two remaining criteria: saving–investment coordination and price level stability.

The interest rate has two jobs to do. It should coordinate household saving decisions with entrepreneurial investment decisions and it should balance the supply and demand for credit. If the supply of credit were always to equal saving and the demand for credit investment, the two conditions could always be met simultaneously. But there is no such necessary relationship between saving and investment on the one hand and credit supply and demand on the other. In Wicksell’s system the banks make the market for credit; they may, for instance, go beyond the mere intermediation of saving and finance additional investment by creating money; the injection of money drives a wedge between saving and investment; this could only be so if the banks set the market rate below the ‘natural’ value required for the intertemporal coordination of real activities. The resulting inflation and endogenous growth of the money supply would continue as long as the banking system maintained the market rate below the natural rate. Wicksell analysed the case of a ‘pure credit’ economy in which the cumulative process could go on indefinitely, but he also pointed out that, in a gold standard world, the banks would eventually be checked by the need to maintain precautionary balances of reserve media in some proportion to their demand obligations.

Wicksell used the model to explain long-term trends in the price level and was critical of those who, like Gustav Cassel, used it to explain the business cycle. Nonetheless, subsequent developments of his ideas went altogether in the direction of shorter-run macroeconomic theory. In Sweden, Erik Lindahl (1939) and Gunnar Myrdal (1939) refined the conceptual apparatus, in particular by introducing the distinction between ex ante plans and ex post realizations and thereby clarifying the relationship between Wicksellian theory and national income analysis. The attempts by the Stockholm School to improve on Wicksell’s treatment of expectations were less successful, however, producing a brand of generalized process-analysis in which almost ‘everything could happen’.

In Austria, Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek focused on the allocational consequences of the Wicksellian inflation story. The Austrian overinvestment theory of the business cycle became known to English-speaking economists primarily through Hayek’s Prices and Production (1931). In expanding the money supply, the banks hold market rate below natural rate. At this disequilibrium interest rate, the business sector will plan to accumulate capital at a rate higher than the planned saving of the household sector. If the banks lend only to business, the entrepreneurs are able to realize their investment plans whereas households will be unable to realize their consumption plans (‘forced saving’). The too rapid accumulation of capital (which also has the wrong temporal structure) cannot be sustained indefinitely. The eventual collapse of the boom may then be exacerbated by a credit crisis as some entrepreneurs are unable to repay their bank loans.

The Austrian ‘monetary’ theory of the cycle has been overshadowed first by Keynesian ‘real’ macrotheory and later by monetarist theory. One problem with it is the firm association of inflation with overinvestment. The US stagflation in the 1970s, for example, will not fit. The reasons lie largely in the changes that the monetary system has undergone. Most obviously, commercial banks now lend to all sectors and not only to business. More importantly, however, inflation in a pure fiat regime does not tend to distort intertemporal values in any particular direction (although it may destroy the system’s capacity for coordinating activities over time): it simply blows up the nominal scale of real magnitudes at a more or less steady or predictable rate. In contrast, the Austrian situation that preoccupied Mises and Hayek in the late 1920s was one of credit expansion by a small open economy on the gold standard. Given the inelastic nominal expectations appropriate to this regime, the growth of inside money would be associated with the distortion of relative prices and misallocation effects predicted by the Austrian theory.

In England, Dennis Robertson and J. Maynard Keynes both worked along Wicksellian lines in the 1920s. The novel and complicated terminology of Robertson’s Banking Policy and the Price Level (1926) may have made the work less influential than it deserved. Keynes’s Treatise on Money (1930), although also remembered as a flawed work, nonetheless remains important as a link in the development of macroeconomics from Wicksell to the General Theory.

In the Treatise, Keynes, like Wicksell, assumes that the process starts with a real impulse, that is, a change in investment expectations. Unlike Wicksell, he focuses on deflation rather than inflation. For Keynes with his City experience, the interest rate was determined on the Exchange rather than set by the banks. Consequently, a deflationary situation with the market rate exceeding the natural rate can only arise when bearish speculation keeps the rate from declining. When saving exceeds investment, therefore, money leaks out of the circular spending flow into the idle balances of bear-speculators. Thus the analysis stresses declining velocity rather than endogenously declining money stock. At this stage of the development of Keynesian economics, the banks are already edging out of the theoretical field of vision and the original connection of natural rate theorizing with criteria for neutral money is by and large severed.

The model of the Treatise still assumes that, when market rate exceeds the natural rate, the resulting excess supply of present goods will cause falling spot prices but not unemployment of present resources. Although the focus is on a disequilibrium process, at a deeper level the theory is still comfortingly classical. As long as the economy remains at full employment, the bear-speculators who are maintaining the disequilibrium are forced, period after period, to sell income-earning securities and accumulate cash at a rate corresponding to the difference between household saving and business sector investment. Automatic market forces, therefore, are seen to put those responsible for the undervaluation of physical capital under inexorably mounting pressure to allow correction of the market rate. And the longer those agents acting on incorrect expectations persist in obstructing the intertemporal coordination of activities, the larger the losses that they will eventually suffer.

In the General Theory, Keynes starts the story in the same way: investment expectations take a turn for the worse – ‘the marginal efficiency of capital declines’; the speculative demand for money prevents the interest rate from falling sufficiently to equate ex ante saving with investment. But at this point the General Theory takes a different tack: the excess supply of present resources, which is the immediate result of the failure of intertemporal price adjustments to bring intertemporal coordination, is eliminated through falling output and employment. Real income falls until saving has been reduced to the new lower investment level.

This change in the lag-structure of Keynes’s theory (‘quantities reacting before prices’) is not necessarily revolutionary by itself. But Keynes combines it with the assumption that the subsequent price adjustments will be governed, in Clower’s terminology, not by ‘notional’ but by ‘effective’ excess demands. For the economy to reach a new general equilibrium, on a lower growth path, interest rates should fall but money wages stay what they are. Following the real income response, however, saving no longer exceeds investment so there is no accumulating pressure on the interest rate from this quarter; at the same time, unemployment does put effective pressure on wage rates. Interest rates, which should fall, do not; wages, which should not, do. From this point, Keynes went on to argue that nominal wage reductions would not eliminate unemployment unless, in the process, they happened to produce a correction of relative prices (an eventuality that he considered unlikely). This argument was the basis for his ‘revolutionary’ claim that a failure of saving–investment coordination could end with the economy in ‘unemployment equilibrium’.

Prior to the General Theory, writers in the Wicksellian tradition had generally treated ‘saving exceeds investment’ and ‘market rate exceeds natural rate’ as interchangeable characterizations of the same intertemporal disequilibrium. The basic proposition could be couched equally well in terms of quantities as in terms of prices. In the General Theory, Keynes moved away from this language. Constructing a model with output and employment variable in the short run was a novel task and Keynes, as the pioneer, was unsure in his handling of expected, intended and realized magnitudes. Thus his preoccupation with the ‘necessary equality’ of saving and investment (ex post) was to produce endless confusion over interest theory. If saving and investment are always equal, the interest rate cannot be governed by the difference between them; nor can the interest rate mechanism possibly coordinate saving and investment decisions. To Keynes, two things seemed to follow. One was the substitution of the liquidity preference theory of the interest rate for the loanable funds theory; the other was the abandonment of the concept of a ‘natural’ rate of interest (Leijonhufvud 1981, pp. 169 ff.)

These were not innocent terminological adjustments. The brand of Keynesian economics that developed on the basis of the IS–LM model had only a shaky grasp at the best of times of the intertemporal coordination problem originally at the heart of Keynes’s theory. The Keynesian position shifted already at an early stage back to the pre-Keynesian hypothesis of money wage ‘rigidity’ as the cause of unemployment. This switched the focus of analytical attention away from the role of intertemporal relative prices (the market rate) in the coordination of saving and investment to the relationship between aggregate money expenditures and money wages. This brand of ‘Keynesian’ theory which excludes the saving–investment problem (that is, excludes the market-natural rate problem) could hardly be distinguished from Monetarism in any theoretically significant way.

Monetarism gained enormously in influence during the inflationary 1970s. But its period of dominance was brief. This was so in part because, in its New Classical form, it was both theoretically implausible and empirically weak. In part, however, it was swept aside by a wave of innovations in payments technology and in forms of short-term credit that undermined the stability of the relationship between the money stock and income which had been the very linchpin of monetarist doctrine.

Most recently, this has led to a return to a basically Wicksellian doctrine of what monetary policy should aim to accomplish and how it should be conducted. Leading central banks are now committed to targeting the inflation rate (rather than the price level) and use the interest rate as their primary instrument for pursuing that goal. This policy doctrine has been elaborated in the book by Woodford (2003) which borrows its title from Wicksell.

Bibliography

Cassel, G. 1928. The rate of interest, the bank rate, and the stabilization of prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics 42: 511–529.

Hayek, F.A. 1931. Prices and production. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Humphrey, T.M. 1986. Cumulative process models from Thornton to Wicksell. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Review 18–25.

Keynes, J.M. 1930. A treatise on money, 2 vols. London: Macmillan.

Keynes, J.M. 1936. The general theory of employment, interest and money. London: Macmillan.

Leijonhufvud, A. 1981. The Wicksell connection. In Information and coordination, ed. A. Leijonhufvud. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lindahl, E. 1939. Studies in the theory of money and capital. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Myrdal, G. 1939. Monetary equilibrium. Edinburgh: William Hodge.

Palander, T. 1941. On the concepts and methods of the Stockholm school. In International economic papers, vol. 3. London: Macmillan, 1953.

Robertson, D.H. 1926. Banking policy and the price level. New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1949.

Taylor, J.B. (ed.). 1999. Monetary policy rules. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wicksell, K. 1898. Interest and prices. New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1962.

Wicksell, K. 1906. Lectures on political economy, vol. 2. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1934.

Woodford, M. 2003. Interest and prices: Foundations of a theory of monetary policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Leijonhufvud, A. (2018). Natural Rate and Market Rate of Interest. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_1216

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_1216

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-95188-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-95189-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences