Boeing is grappling with a profound crisis that threatens to undo the company’s century-old reputation for safety.

The worldwide grounding of the 737 Max, Boeing (BA)’s best-selling product, raises alarming questions about whether the company rushed the jetliner’s development. And even after the first fatal 737 Max crash last year, Boeing (BA) failed to heed warnings from pilots who urged the company to take emergency actions.

The flying public has been shaken by the pair of 737 Max crashes that killed a combined 346 people. Pilots are concerned. Regulators are under fire for approving the planes. Shareholders have lost money. And airlines that were counting on the 737 Max are piling up losses.

To fix the problem, the company’s board continues to rely on the Boeing management team that oversaw the 737 Max’s flawed development.

Boeing’s management team and board of directors are under immense pressure, not just to get the 737 Max back in the air, but to reassure the public about the soundness of the company’s culture and processes.

That will be a difficult task given that the executive team of Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg, a Boeing lifer who’s been with the company for 34 years, is responsible for creating that culture. Boeing faces serious accusations that the plane was rushed into service with new software believed to have contributed to two fatal crashes and without providing adequate training to pilots.

“There is a crisis of confidence,” said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, senior associate dean for leadership studies at the Yale School of Management. “Boeing was captured by its own culture. They have become a victim of that overconfidence.”

Add ‘Sully’ to the Boeing board?

To restore confidence in Boeing’s once-sterling reputation for safety, corporate governance experts and analysts urged the world’s largest aerospace company to take more dramatic steps, including shaking up its board of directors, curbing Muilenburg’s power, owning up to what went wrong with the 737 Max and hiring a credible outsider to investigate.

The board at Boeing, the world’s largest aerospace company, may need a makeover. Current directors include big names like Nikki Haley, former Continental Airlines CEO Lawrence Kellner and ex-Aetna boss Ronald Williams.

“They have excellent people on the board – but so did Wells Fargo,” said Sonnenfeld.

Glass Lewis recommended the defeat of Kellner, head of Boeing’s audit committee, because of concerns that the committee “should have taken a more proactive role” identifying the 737 Max risks.

Boeing, however, supported Kellner staying on the board. He was easily re-elected.

Sonnenfeld urged Boeing to shrink the size of its board and consider replacing Caroline Kennedy, the former US ambassador to Japan. He questioned what Kennedy is bringing to the board and suggested adding instead Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger. The hero US Airways pilot credited with the “Miracle on the Hudson” is “emblematic of public safety and trust,” Sonnenfeld said. Sullenberger has criticized Boeing and the FAA for “conflicts of interest” in the 737 Max crisis.

“He’s the perfect choice,” said Richard Aboulafia, vice president of analysis at the Teal Group, an aircraft industry analysis firm.

Aboulafia urged Boeing to add people with more engineering experience to its board and said the company needs to have an honest discussion about what went wrong.

Lawmakers have criticized Boeing for reports that its own test pilots lacked crucial details in a flight-control system implicated in the crashes.

“Safety deserves priority over profits,” Senator Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat from Connecticut, said in a tweet earlier this month that urged “close scrutiny” of the matter.

Next steps for Boeing

Boeing doesn’t have to look far to find examples of other companies responding to challenges.

Sonnenfeld said the “gold standard” is Johnson & Johnson’s (JNJ) response in 1982 when three people died after taking cyanide-laced Tylenol. Even though J&J didn’t know the cause, the company quickly recalled Tylenol from store shelves, issued a national warning and opened a hotline for customers. That rapid response stands in contrast with Boeing’s.

General Motor CEO Mary Barra was also credited with leading the company’s response to a flawed ignition switch that killed 124 people.

“Mary’s instincts – and the GM board – did extremely well,” said Sonnenfeld.

Wells Fargo (WFC), on the other hand, is still struggling to recover from its own scandal, two-and-a-half years later.

Michelle Lowry, a professor at Drexel University, said Boeing needs to hire a credible outsider to lead an in-depth probe of what happened – and then make the findings public.

“That’s very risky to Boeing. It will expose them to all kinds of litigation risk,” said Lowry. “But how is Boeing going to recover trust and its reputation without real, serious changes?”

Angry pilots

Reports about how Boeing developed the 737 Max and responded to safety concerns has severely damaged the brand. The response, in particular, raises questions about why the board hasn’t acted more swiftly to make changes to the company’s oversight personnel and systems.

In April 2017, Muilenburg bragged about how quickly Boeing brought the 737 Max to market and praised the FAA’s “streamlined” certification process, which Boeing lobbied heavily for. It gave Boeing significant power to ensure the safety of the 737 Max on its own.

“We’re already seeing some benefits there of the work that’s being done with the FAA,” Muilenburg told Wall Street analysts on a conference call.

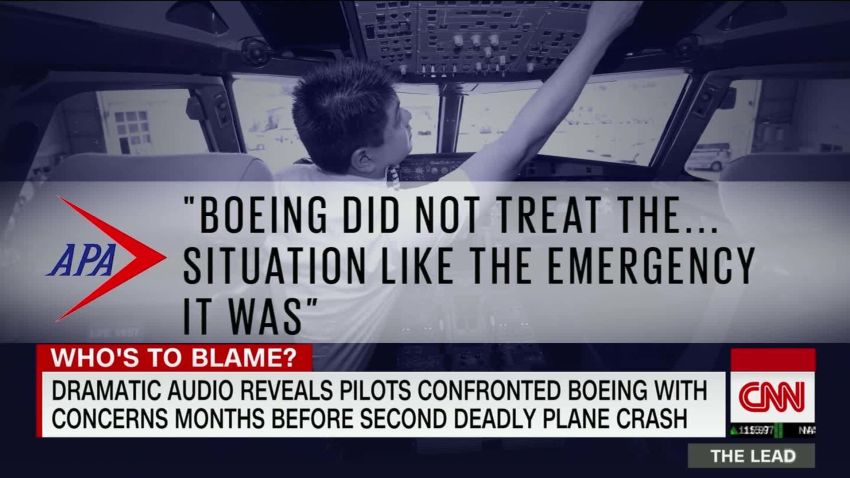

In November, just weeks after the crash of a Lion Air 737 Max into the Java Sea, American Airlines pilots confronted Boeing about a computerized anti-stall system implicated in the crashes, according to audio obtained by CNN and other outlets.

“These guys didn’t even know the damn system was on the airplane,” a pilot says, apparently referring to the Lion Air pilots. “Nor did anybody else.”

A Boeing executive told pilots that software changes were coming to the program, the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, perhaps in as little as six weeks. But Boeing didn’t want to rush a fix to MCAS before knowing what was wrong.

Four months later, a 737 Max operated by Ethiopian Air crashed in Ethiopia.

“It’s just stunning,” said Lowry, the Drexel professor. “After one crash, you would think the board would have been all over this and the company would have taken dramatic actions.”

Last month, Muilenburg announced a new board committee of independent directors charged with examining past and future development issues.

“Safety is our responsibility, and we own it,” Muilenburg said in a statement then. “When the MAX returns to the skies, we’ve promised our airline customers and their passengers and crews that it will be as safe as any airplane ever to fly.”

‘Inherent conflict’ at Boeing

But the latest revelations will only increase calls for Boeing’s board of directors to take further actions, even as the company grapples with multiple investigations from the FAA, US regulators, foreign safety agencies, Congressional committees and a criminal probe from the Justice Department.

“Culture comes from the top,” said Lowry.

Like other major companies, Boeing has a glaring corporate governance issue: Muilenburg is the CEO as well as the chairman of the board. That means he’s in charge of both the management and the oversight of that management.

“There’s this inherent conflict,” said Lowry, who predicted Muilenburg will eventually lose his chairman title.

Shareholder watchdogs Glass Lewis and Institutional Shareholder Services urged Boeing investors to vote in favor of a proposal calling to split those roles at the company’s annual meeting last month. ISS specifically cited the “serious” concerns raised by the 737 Max.

“Any missteps” in fixing the 737 Max issue or “any repeat of the problem” in future problems “could have a devastating impact on the company’s business prospects, its brand and its reputation, for years,” ISS warned.

But shareholder resolutions are difficult to win, especially when the company is fighting them. Only 34% of shares supported the measure. That’s higher than last year but still well shy of the required majority.

If the company decides to commit to change to restore trust with customers, regulators and the public, it will be left to the board to choose a new direction and makeup for the company. So far, Boeing has been slow to take the bold steps required to stop the crisis.

CNN’s Chris Isidore contributed to this report.