Imagine Walt Disney announced he was shutting down his animation studio immediately after releasing Sleeping Beauty and you’ll have some sense of the grief that animation fans suffered when they heard that Hayao Miyazaki was hanging up his brush and Japan’s vaunted Studio Ghibli might vanish along with him. Miyazaki’s movies left a mark on the last three decades that’s almost impossible to overstate—you can see the influence of Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke in Game of Thrones and the Lord of the Rings trilogy, and his My Neighbor Totoro has raised an entire generation of budding anime aficionados—and with 2013’s The Wind Rises and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, both he and fellow visionary Isao Takahata finished their Ghibli careers at the peak of their powers.

As it turns out, Miyazaki is about as good as retiring as Jay-Z, and the “brief pause” in Ghibli’s output announced after his retirement may end up being just that. He is reportedly already working on another feature under the Ghibli banner. But while Ghibli’s future remains uncertain, there’s Studio Ponoc, a new concern founded by many of Ghibli’s former (and perhaps future) animators, and carrying over many of its traditions.

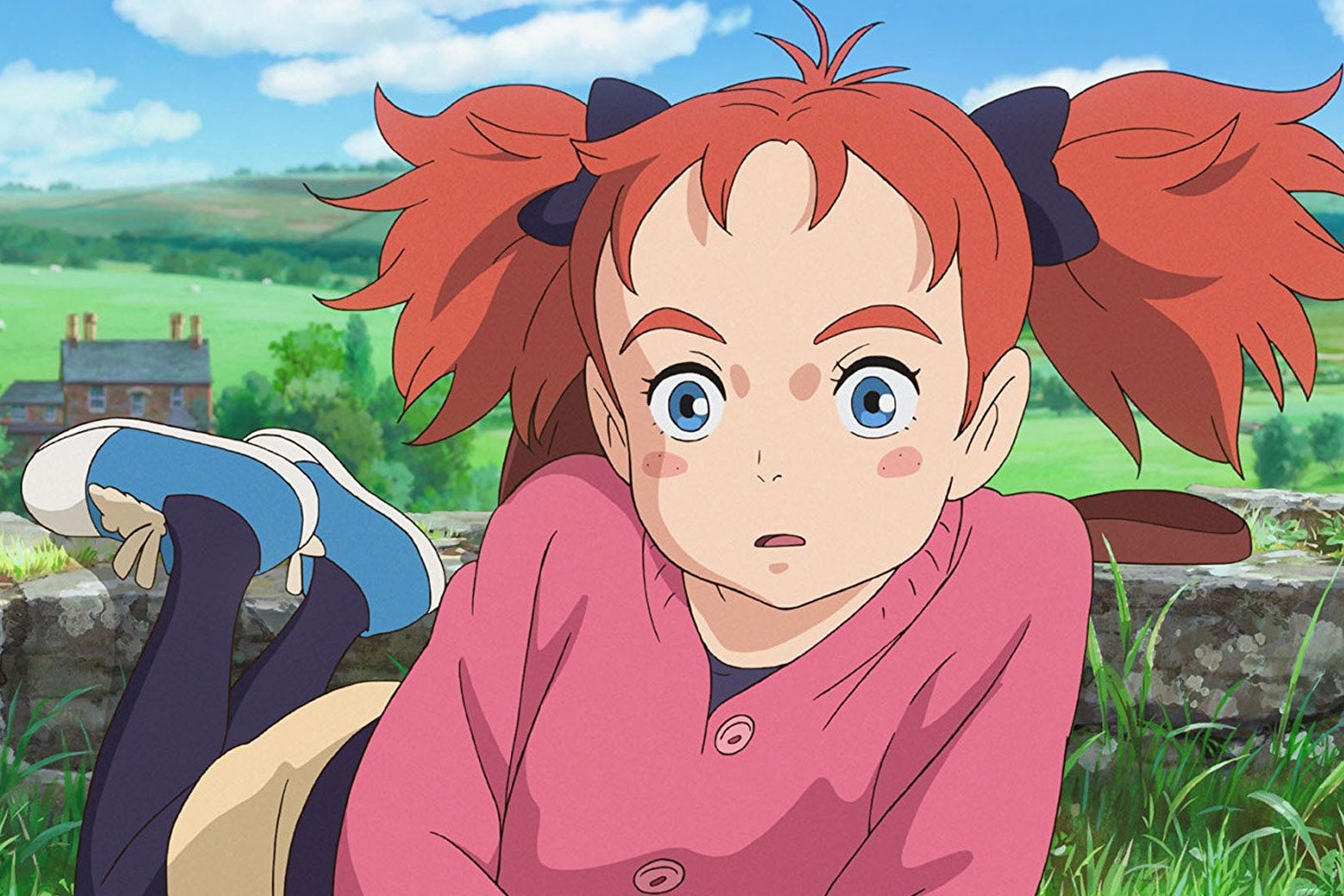

From the middle distance, Mary and the Witch’s Flower, Studio Ponoc’s inaugural release, is almost indistinguishable from a Ghibli film proper. Like many of Ghibli’s movies, it’s adapted from an English-language children’s book—in this case Mary Stewart’s 1971 novel The Little Broomstick—and centers on a young female protagonist (a redhead, even) who discovers that the world is full of stranger things than she ever imagined. There’s the familiar interplay between vivid natural backdrops, which range from impressionistic to almost photoreal, and elastic, cartoony figures.

Even the names are familiar: The director of Studio Ponoc’s first movie, Hiromasa Yonebayashi, was also the director of Ghibli’s last, 2014’s When Marnie Was There, and Miyazaki, Takahata, and longtime Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki’s names turn up in the credits, although you have to watch through the end to see them.

Is it ungrateful, then, to feel that Mary and the Witch’s Flower is a little too much like a Ghibli movie? The story of a young girl (voiced by The BFG’s Ruby Barnhill) who discovers that she has been born into a long traditional of witchcraft, the film—adapted by Yonebayashi and Riko Sakaguchi, with an English-language script by David Freedman and Lynda Freedman—is predicated on a sense of wonder, but so much of its world feels familiar, if comfortably so, like a favorite band playing their old hits. The oozing protoplasm that attacks Mary as she’s whisked off to the magical confines of Endor College—initially resembling a swarm of flying, gelatinous dolphins—recalls Mononoke’s wriggling demonic infections, and Endor College itself feels like a descendant of Castle in the Sky’s Laputa. (That Stewart’s source novel may have itself been plundered for other pop-cultural properties is suggested when Mary catches a glimpse of another novice student, a boy in floppy robes and round eyeglasses, as he fumbles through a spell.) Madam Mumblechook (Kate Winslet), Endor’s headmistress, could be any of the imperious matrons dotted throughout Miyazaki’s oeuvre, and with his bulbous nose and drooping mustache, the eccentric Doctor Dee (Jim Broadbent) looks like a cousin to Spirited Away’s multiarmed Kamaji. And all of this is without mentioning Kiki’s Delivery Service, Miyazaki’s own film about a young witch and her cat. Given that some of Mary’s creative team worked on some of those films, it’s less a matter of copying Ghibli’s style than extending it, but as swoony as some of its deftly painted vistas can be, it’s decidedly lacking the shock of the new.

The world is not so full of beauty that one can wave away Mary’s visual majesty, especially now that its hand-drawn style is nearly a thing of the past. But the flaws in its writing are harder to overlook. The relationship between Mary and the luminescent flower whose berries awaken her powers is not mysterious so much as ill-defined, and her relationship with Peter (Louis Ashbourne Serkis), a fellow Endor student, is even wiftier. (The character himself is barely more than a haircut draped over a cloud of vague pleasantness.) There are interesting ideas knocking about inside the film, including that electricity is also a form of magic and that sometimes the wisest thing to do with power is to reject it. But they fall by the wayside or wriggle away, without the guiding intelligence that might have built them into something greater. One shot after another elicits wide-eyed awe, but eventually it’s like going to a play and spending the whole time staring at the sets. The movie’s incredible to look at, but not always so thrilling to watch.