Overview

This guide investigates how "the South" has been an ideological and experiential focus for the development of distinctive religious forms and how some of the forms of religion identified with the South—evangelicalism, fundamentalism, pentecostalism—have dispersed throughout the nation.

Introduction

Hope Mills Rapid Lube Sign, Hope Mills, North Carolina, March 20, 2014. Photograph by Flickr user Gerry Dincher. Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 2.0.

Religion has been a formative experience for those living in the US South. "It's just there," said William Faulkner in explaining why religion appeared so often in his novels and stories (Glynn and Blotner, 1959, 41). It was not a matter of whether Faulkner or other southerners were necessarily believers themselves, but it was a tangible part of the landscape of places where many people were passionate and open about their faith. By Faulkner's time, evangelical Protestantism had already long dominated the South as a whole, and this proselytizing religious tradition believed in publicly testifying about the faith by whatever means necessary, making its public presence especially widespread. Historian John Lee Eighmy coined the phrase "cultural captivity" to suggest that the South's predominant churches reflected a culture of "southernism" shaped by economic and racial elites, but at the same time, churches themselves shaped the institutional and personal development of the South and its people. (Eighmy, 1972) Often theologically and socially conservative, religion in the South also provided the rationale and organization for progressive reform. Religion advanced the cause of slavery, yet it also inspired slave rebellion. Religion comforts and sustains suffering people, and a South of slavery, Civil War, poverty, racial discrimination, economic exploitation, ill health, and illiteracy surely needed that crucial support. As the South went through the slow and sometimes agonizing process of modernizing, religion provided justification for the wealthy to profit from economic development, but it also gave meaning to those bearing the burdens of economic change without proper recompense. Throughout such changes, religious organizations remained central institutions of southern life.

A consideration of the regional contexts of religion in the South directs attention to the geographic, environmental, demographic, economic, social, and cultural factors of religious development. Spatial and social places mattered. Commonalities existed across social barriers but experiences varied depending on whether you were a Mississippi Delta man or an Upcountry woman, black or white, rich or poor, Southern Baptist or African Methodist Episcopal, Episcopalian or Pentecostal. From early settlement, religious forms adapted to a stratifying social reality but also enabled southerners to give voice to yearnings that transcended hierarchies. Time, as well as place, mattered in understanding southern religion. Religion in the colonial period was considerably different from that in 1830, and subsequent generations experienced dramatic social changes that would affect religion. Evangelicalism came to dominate the religious life of southerners, in ways distinctive to the nation. Although embodied in a myriad of denominational forms, evangelical Protestantism has served as an unofficially established religious tradition, powerful in worldly resources, institutional reach, moral authority, and cultural hegemony.

Demographics was as fundamental as place and time in creating a regional religion in the US South. Indigenous peoples had their own religious systems that the coming of European Christianity disrupted, but the Native American presence left a spiritual legacy. More tangible influences of spirit-related health practices and site-related sacred spaces linger from this earliest time of Native American habitation. As the South became a predominantly biracial society in the nineteenth century, the coming together of the religions of western Europe and western Africa provided the essential background for the later development of religion in the South. European theology, liturgy, and morality would come to predominate, but not without considerable imprint from African spirituality. Slaves transmitted to their descendents particular styles of worship, mourning rites, and herbal practice rooted in religious systems of Africa.

Although its boundaries have sometimes been hard to pin down and have varied from era to era, "the South" has been an ideological and experiential focus with significance for development of distinctive religious forms. Evangelical dominance developed at the same time as sectional political consciousness crystallized in the early nineteenth century, and religious groups, both culturally dominant ones and dissenters, lived within a society constrained by the orthodoxies of a sectional society often at odds with national expectations. Religious groups in the South sometimes used sectional identification to define themselves against outsiders—especially northerners—who used their own religious language and ideas to condemn the immorality of the South. Indeed, religion in the South typically carried a heavy responsibility of defending "the South" itself because attacks against it were as often based on morality as on economics, politics, or other rationales. Ministers were peculiarly positioned to interpret sectional experience as divinely sanctioned when under attack, and they repeatedly did so.

Region also matters in understanding religion in the South because of the variety of regional contexts that have existed within the geographical South. The Upper South of hill country and mountains nurtured different experiences and cultural forms from those in the Lower South. "The South" has included such specific regions as the Atlantic Coast Tidewater, the Piedmont, the Black Belt, the Mississippi Delta, the Piney Woods, Acadian Louisiana, and the Gulf Coast. The long predominance of evangelical Protestantism in the South has been a crucial backdrop for religious development, but that religious tradition includes many specific groups, often with regional meanings within the broader South.

The Baptists, for example, represent the largest religious denomination in most counties of the South; but their greatest strength reaches from southern Appalachia, into the Deep South states of Georgia, Alabama,and Mississippi, into northern Louisiana and east Texas, and into southern Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma—creating a Baptist domain within the US South, which is itself characterized within the national context as more Baptist than anything else. The mountains of east Tennessee were an important hearth for white Pentecostalism, giving birth to the Church of God, while the Deep South of Mississippi and nearby Memphis nurtured black Pentecostalism through the Church of God in Christ. The Churches of Christ, a theologically conservative and morally strict group that grew out of the Presbyterians, are often one of the numerically largest and culturally powerful religious groups from middle Tennessee, down through north Mississippi, Arkansas, and into central and west Texas, but the group is hardly known in other parts of the South.

Religious traditions that are outside the predominant evangelical Protestantism have special significance within particular places in the South. Ethnic groups planted and sustained religious traditions in regional enclaves outside the evangelical Protestant hegemony. Roman Catholics have dominated in south Louisiana, dating from sixteenth and seventeenth century French settlement, creating a unique landscape in the South, but Catholics also heavily influenced life in Hispanic south Texas, Cuban areas of Florida, and along the Gulf Coast with its early French and Spanish settlement. Catholics were also a historic presence in Maryland and Kentucky, even nurturing there a prominent twentieth-century spiritual presence in Thomas Merton. Jews have been small in numbers in the South, which has helped shape their peculiar patterns of accommodation and resistance to the overall culture. The geography of Jews in the South is usually depicted as a predominantly an urban one, to some degree, with notable communities in such cities as Atlanta, Memphis, Charleston, and Miami, but Jews have been a perhaps even more significant presence in small towns throughout the South. Central Texas has had a sizeable Lutheran presence, dating from German settlement in the 1800s, while the Carolina Piedmont had been historic home to Quakers, Moravians, and other Protestant dissenters.

Beginnings to 1830

South side of St. John's Episcopal Church, St. John's Episcopal Church, Hampton, Virginia, March 26, 2007. Photograph in public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons license CCO 1.0. Established in 1610, St. John's is the oldest English-speaking parish in continuous existence in the United States.

Attention to the historical development of religion in the South underscores dramatic changes and ways in which religion has entered into the ideology and experience of southerners. Anglicanism, an American version of the English national religion, was the first dominant religious tradition in the South, but dissenting Protestant sects, Catholics, and Jews were also present in the southern colonies. Virginia was especially significant as the home to Anglicanism, becoming the established church early on. Maryland, in its origins, represented an early version of southern religious pluralism, established as a potential refuge for Roman Catholics but also attracting Puritans, Quakers, and Anglicans. After the Glorious Revolution in England in the 1680s, Maryland adopted Anglicanism as the state church of the colony, as did the Carolina colonies and eventually the rest of the southern colonies. Lay influence made for a distinctive Anglicanism, compared to the Church of England. Without a bishop in the colonies and with the predominant secular, materialistic values of a plantation society, the Anglican church was institutionally and culturally weak, but its presence did provide some degree of unity across the colonies, with ministers holding the main religious worship services in the South through the early 1700s, teaching a common theology and moral values, and operating schools. A distinctive group of French Protestants in South Carolina, the Hueguenots, mostly joined the Anglican church there.

Anglicanism left its stamp on the later culture of the South through its embodiment of an influential social model. Anglican ministers had respected social and political authority and allied themselves with the gentry, and upper-class southerners would long admire the Anglican embrace of social class differences, along with paternalistic responsibilities and benevolence. When the Anglican church was disestablished after the American Revolution, its descendant, the new Episcopal church, would continue to attract members associated with the southern social elite.

Evangelicalism began its rise to influence in the South during the mid-eighteenth century. Evangelical Protestantism is a religious tradition that prizes religious experience over liturgy, theology, and other forms of religious life. Calvinist pessimism about human nature was a crucial progenitor of evangelicalism, giving it a characteristic concern for the inevitability of sinfulness and the need for a strong religious community and discipline to contain human frailty. As evangelical Protestantism developed, however, it came to be equally characterized by the hope of redemption. Its theology came to stress that God's grace made salvation possible for those who accepted it. This recognition encouraged preaching that sought converts, giving birth to the camp meetings and revivalism that would become such a central part of southern life.

Evangelicalism in the South appeared with the rise of dissent within Anglican society. English preacher George Whitefield came to the southern colonies as well as others along the Atlantic Coast, and his preaching helped to fire the enthusiasm of the Great Awakening. He offered the hope of a "new birth," an emotional conversion experience that resulted from intense preaching that moved many people who had been unmoved by Anglican sacramentalism as well as that elite denomination's perceived worldliness. While the impact of the Great Awakening in the South was limited, it did lead northern Presbyterians, such as the Rev. Samuel Davies, to settle in Virginia and establish an evangelical presence. More important than the Great Awakening in changing the Anglican dominance of religion in the South was the movement of increasing numbers of settlers into backcountry areas of Virginia and the Carolinas after 1750. Attracted by inexpensive land, Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, Separate Baptists from the northern colonies, and German Protestants moved into the Piedmont, resulting in a surge of new Presbyterian and Baptist congregations, as well as a new presence of Quakers, Lutherans, German Reformed Methodists, and pietistic Protestant sects. All of these new religious influences appealed to the plain folk of the rural and backcountry areas and resulted in the growing marginalization of Anglicans, which was made complete with the overthrow of English authority during the American Revolution. By the 1790s, religious freedom and denominational competition for members represented a new religious sensibility in the South, as across the new nation.

Pioneers in the great religious reformation of the nineteenth century, ca. 1885. Engraving by John Chester Buttre featuring portraits of Thomas Campbell, B.W. Stone, Walter Scott, and A. Campbell. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, www.loc/gov/pictures/item/98508288/.

The Great Revival (1800-1805) launched the Second Great Awakening in the South, beginning on the frontier, in Logan County, Kentucky. The Cane Ridge Revival was the largest associated with this awakening, attracting 25,000 worshippers in the summer of 1801, to hear extended preaching. Plain folk in the Upcountry found a passionate new religion and Cane Ridge became a hearth for grassroots evangelical growth. The Second Great Awakening was national in scope, as Baptists and Methodists, especially effective at recruiting plain folk, rose to new prominence. They became the center of a more democratic religion complementary to the politics of the early nineteenth century that empowered plain folks in the South and elsewhere.

Evangelicals, as historian Rhys Isaac notes, initiated a countercultural movement to gentry planter culture. They saw religious conversion as a transforming experience that led them to embrace an egalitarian fellowship with the redeemed, whether lowly in societal terms or not. Slaves, women, Indians, and the socially marginalized were welcomed as enthusiastic believers, who embraced individualistic conversion and proclaimed a rigorous moral austerity. The planter way of life with its indulgence and worldliness, became a target for criticism by young evangelical preachers, who were often itinerants and especially suspicious of the powers that be in a hierarchical society. Women prayed, prophesied, exhorted and in other ways exercised their spiritual gifts in unprecedented ways. Evangelicals insisted that converts take up the cross of Jesus, sometimes alienating not only planters but plain folk men with their radical vision that empowered all who put spiritual equality ahead of earthly values. This empowerment was perhaps especially significant in terms of African Americans in the South. Anglicans had been ineffective in efforts to convert slaves, but early evangelicals criticized slavery, sought black converts, and licensed black exhorters. The first black congregation in the southern colonies, founded in Silver Bluff, Georgia, in 1773, was Baptist, and Mechal Sobel has documented dozens of black Baptist churches by 1830. Most slaves worshipped, though, as part of biracial churches that would become even more numerous after 1830.

In time, evangelicals compromised their early social radicalism as part of their accommodation to existing hierarchies of southern life and their attempt to gain greater influence. In the first four decades of the nineteenth century, settlers from southern states moved into the Old Southwest, creating a new Cotton Kingdom and extending familial and ideological relationships across what we would now call the Deep South. Evangelicals were expansive and increasingly successful in this area, as they abandoned their original hostility to slavery and restricted black preachers. Evangelical doctrine increasingly restricted women as well, taking away their right to vote in congregations, limiting their public role and emphasizing family life as a new evangelical ideal. Evangelicalism still focused on aggressively seeking converts, demanding moral discipline, and dominating local congregational communities, but it increasingly influenced discussions of public issues as well, providing moral meaning to a society that was economically and politically in formation.

Emblematic of the evangelical consolidation of influence in the early nineteenth century was the attempt to convert Native Americans. As settlers moved into the Old Southwest, pressures mounted for removal of Indians from their native lands. Long before this moment, traditional Indian religion had evolved through contact with Christian missionaries. This contact had disrupted Native societies and besieged traditional religious identities. A Cherokee Ghost Dance Movement (1811-1813) produced apocalyptic visions that predicted the destruction of whites, but its failure proved to be a turning point in that tribe's history, as increasingly Christianity replaced traditional Indian worldviews. Baptists first sent missionaries to the Cherokee Nation shortly after that, in 1819, with Methodist circuit riders appearing in late 1823. Evangelical stress on spiritual experience over doctrine, an informal worship ritual, the empowerment of Cherokees themselves as evangelists, and congregational-based authority all promoted acceptance of Protestantism among the Cherokees and other Southeastern Indians. When the federal government forced removal of the Five Civilized Tribes to the Indian Territory, the Indians took forms of evangelical religion with them and planted them in what would become a border area of the South.

Becoming a Sectional Religion, 1830–1880

The years around 1830 were fateful ones for a developing sense of a southern sectional identity. While social and cultural distinctiveness had already developed below the Mason-Dixon Line, the Missouri Controversy (1819-21) nurtured a new political significance to differences between a "North" and a "South." The vote on extension of slavery into the West seen in the debate on admitting Missouri to the Union went along strictly sectional lines, North and South, with profound political significance for the division of power within the Union. Two events around 1830 added to the growing sectional consciousness, and both had religious meaning. William Lloyd Garrison's publication of The Liberator called for the immediate end of slavery, making the issue a predominantly moral one. Shortly afterwards, Nat Turner's Rebellion brought a large-scale slave uprising, with Turner acting out of prophetic belief, rooted in the Bible's Old Testament, that he would bring his people out of bondage. After these two compelling events, southern whites used religion to carve out new relationships with northern abolitionists by attacking their morality and with southern blacks, who represented to them internal subversion based in misreading the same scriptures they read.

One white response to these forces was a new mission to the slaves. South Carolina Methodists were most successful in establishing specific missions, while an evangelical alliance led by minister-planter Charles Colcock Jones in Liberty County, Georgia, promoted an idealistic vision of an evangelical biracial community that would lead to the end of slavery. These initiatives were of limited impact, but they symbolized a new willingness among slaveowners to allow white preachers and, sometimes, black exhorters to preach the gospel to their slaves. The gospel that appeared here was one that stressed moral discipline and obedience of slaves to masters, with ultimate hopes for redemption in heaven. White religious leaders assumed new responsibilities for the fate of slave souls, which was a response to their overriding concern to convert everyone, their concern to achieve greater social control of slaves, and their belief that slavery was not an inherently immoral institution.

Blacks responded to the new evangelical message, though, for different reasons than those advanced by slaveowner-sanctioned preachers. The potential for spiritual equality, and even the hope for earthly liberty, could be taken from evangelicalism, and that held a powerful appeal for slaves. Evangelicalism's informal, spirit-driven style of worship could evoke remembrances of the religious ecstasies of African dance religions. Nowhere else in southern society did African Americans find the status that they could achieve in churches. Some African Americans worshipped in separate black churches, but most slave worship was in biracial churches. Black Baptists and Methodists had shaped evolving evangelicalism since the earliest revivals. The generation before the Civil War represented the one moment in southern religious life when blacks and whites shared the same ritual and spatial setting, listened to the same sermons, partook of communion together, and shared church disciplinary procedures. The interaction within biracial churches represented a foundation for later spiritual commonalities among blacks and whites in the South. Slaves also worshipped in secret praise services in the slave quarters—their "invisible religion" (Raboteau, 1978). Here, God stood in judgment of the Christianity of the slaveowners, and slave preachers applied the biblical story of Exodus to their own people, with ultimate liberation a hope. Slave spirituals became the creative group expression of these aspirations. The ring shout was the most distinctive expression of religious worship in the praise service, with African-derived dancing and body movement emphasized. The invisible religion of the slave quarters also included conjure, a system of spiritual influence that combined herbal medicine with magic and sometimes gave surprising authority to slave practitioners who believed they could affect whites as well as blacks.

While slaves saw in the Bible a vision of spiritual liberation, southern white religious leaders increasingly after 1830 used the same scriptures to justify slavery, as part of their defense against abolitionist criticism. One strain of the proslavery argument saw southern society as the last bulwark against an inhumane industrial order that had abandoned Christian orthodoxy. Ministers cited biblical examples of the coexistence of Christianity and slavery, quoted Old Testament approvals of slavery, cited Paul's New Testament letters that taught that servants should obey their masters, and interpreted a passage from the book of Genesis to mean that blacks were descendants of the sinner Ham and destined forever to be bondsmen. Southern writers developed the image of plantations as well-ordered pastoral places, presided over by benevolent patriarchs, an image with deep roots in Western biblical tradition.

Proceedings, Southern Baptist Convention, Augusta, Georgia, May 8–12, 1845. Published by H.K. Ellyson. Courtesy of Baylor University Libraries, Southern Baptist Convention Annuals. Screenshot by Southern Spaces.

Southern religious leaders made a major contribution to promoting southern nationalism by the secession of major denominations. Well before the nation's political parties separated along sectional lines, the churches did so, beginning in the 1840s, when southern Baptists withdrew from fellowship with northern congregations over the issue of whether a slaveowner could be a missionary. Southern Methodists withdrew from other US Methodists after debates on whether a slaveowner could serve as a bishop. One group of conservative southern Presbyterians split from northerners in 1857, and after the Civil War a new Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America appeared. The Episcopalians did not formally divide, but a Confederate Episcopal church did operate during the Civil War years. In the aftermath of the divisions came disputes over who controlled church property in some areas, unleashing fears, angers, and suspicions among religious people and creating disputes over who would control denominational life in border areas. The Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians of the South did not reunite with their northern coreligionists after the war, creating enduring sectional institutions that became perpetuators of a southern cultural identity.

The challenge for Roman Catholics and Jews in the South before the Civil War was to maintain their separate religious identities and yet find ways to accommodate to a biracial society dominated demographically and culturally by evangelical Protestants. Catholics had long been a major presence in the upper South, going back to the founding of Maryland, and in Gulf Coast areas, but the antebellum years saw the coming of Irish and German immigrants who spread the Catholic influence through other areas of the South. Most Catholic immigrants to the United States went to northern cities and formed major communities. This happened in the South also in places like New Orleans and Savannah, but in most places the rural nature of southern life gave a peculiar character to the Catholic church. The small numbers of priests and parishes led the Catholic leadership to spend its resources on building churches, recruiting priests and nuns, and encouraging devotionalism. The leadership also had to cope with interethnic conflicts among French, Irish, and German Catholics. The Catholic Church in the South sanctified the political order of slavery and states' rights, with Bishop Augustin Verot famously delivering a sermon at the beginning of the Civil War that justified slavery in the same proslavery language that other southerners had been using for a generation.

Synagogue, Charleston, South Carolina, ca. 1812. Graphite drawing by John Rubens Smith. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.05439/.

Jews were an early presence in southern colonies, and by 1820 South Carolina had the largest Jewish population in the United States. Early Jewish immigrants to the South were from the Iberian Peninsula, with those from central Europe coming in larger numbers after 1840. They embraced the religious freedom that the nation offered, as well as its economic opportunities. Many became merchants and professionals, carving out distinctive roles in a slave society that did not have a place for immigrant laborers but did welcome their contributions. Jews became active in political and civic activities throughout the nineteenth century, and Jewish elected officials served throughout the South. They justified slavery and became slaveowners; they spoke the language of honor and fought duels to defend it. Despite such assimilation, intolerance of Jews was also a part of southern religious history, with Civil War frustrations leading to Jews' becoming scapegoats for other southerners.

With the inception of the Confederate States of America southern sectional identity became a national identity. Southern religion played a crucial role in buttressing the war effort. For a generation, white ministers had preached that slavery was a divinely-ordained institution, and whatever misgivings many of them had about war, they rallied around the Confederacy and gave moral support through preaching that the southern cause was a holy war. They blessed the troops going off to war and saw victories as God's blessings and defeats as God's chastisements for their failures. Religious institutions declared days of fasting and thanksgiving to encourage understanding of the spiritual nature of the war. Ministers cared for soldiers, preached revivals, led prayer groups, and performed mass baptisms. Behind the lines, women joined with ministers in staging rallies to support the troops, preaching sacrifice for home and God, feeding those in need, teaching the children of veterans, nursing the sick, and leading missionary societies. The war promoted new roles for women in southern religious life, as they took over new responsibilities for praying, counseling, and even conducting home services in the absence of ministers off in the war effort. Because of the disruptions of public worship, religion became more private, and the failure of the Confederate holy war brought a crisis of faith for many white southerners.

The Reconstruction period (1865–1877) brought enormous challenges and major change to religious patterns. War had been disruptive and denominations had to rebuild churches, reincorporate ministers into congregations, and deal with the spiritual traumas among defeated white southerners. Northern religious groups entered the South as missionaries to a benighted people. Northern missionaries wanted to promote reconciliation with southern whites and provide relief and reform for former slaves, but white southerners rejected their efforts, seeing them as an extension of Union armies that had conquered them and wanted to overturn their entire civilization. Whites embraced their sectionally-based evangelical denominations, seeing Confederate defeat as a chastisement from God who was nonetheless preparing his chosen people for coming challenges.

During the era of Reconstruction many Blacks joined northern-based religious groups like the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and they withdrew from the prewar, biracial evangelical churches in which they had once worshipped, creating their own independent churches. This occurred as a result of African American frustration with the unwillingness of white Christians to agree to a truly equal role in participation and governance of local congregations and ecclesiastical associations. The separation of white and black Christians in the South established a pattern of racially segregated worship that has long endured. Blacks now controlled their own religious destinies. Churches became important organizing agencies in the political conflicts of Reconstruction, and afterwards they were among the central institutions of black life in the South. The folk spirituality of the slaves' praise services merged with the denominationalism of evangelical Protestantism to create unique religious institutions.

Religion and the Southern Way of Life, 1880–1940

Defenders of a self-consciously "southern" civilization after the Civil War came to use the term "way of life" to indicate an ideological defense of a peculiar pattern of institutions and attitudes associated with the South. Whites saw their system of paternalistic white supremacy as the essence of a southern civilization, but the "way of life" included countless specific attitudes and customs rooted in cultural beliefs and practices and reified as a constructed social identity. Religious institutions and leaders gave a spiritual gloss on the "southern way of life," infusing it with transcendent significance and blurring the lines between Christianity and southernism. Above and beyond religion's defense of a self-consciously southern ideology, religion in the South was indeed distinctive within national patterns of religion, and it was a central part of life for many people.

From the end of Reconstruction to World War II, a tangible memory of the Civil War experience, increasingly mythologized, haunted white southerners. The spiritual interpretation of Confederate defeat became a sectional civil religion—the religion of the Lost Cause. Its saints were leaders like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, and its ritual celebrations were Confederate Memorial Day and dedications of monuments. Organizations like the United Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy were the epitome of white cultural sanctity, and they regularly used religious language to sacralize the Confederacy. The 1890s witnessed the strengthening of the Lost Cause, with increased organizational and ritual activity, in the same decade as the hardening of white racism. Indeed, the legal codification and institutionalization of white supremacy represented another of those orthodoxies at the heart of the "southern way of life." While white churches often criticized the worst of racial violence, they nonetheless blessed Jim Crow segregation, disfranchisement of black voters, and other manifestations of racism. The second Ku Klux Klan, which appeared after World War I, tapped evangelical moralism as a foundation of its appeal for white purity. Evangelicalism itself stressed individual morality, through avoidance of personal sins, but the churches moved beyond private morality to campaign for laws to regulate gambling, Sunday recreation, dancing, and most importantly, the sale of alcoholic beverages.

After the Civil War these orthodoxies persisted within a developing society that mythologized its past while constructing forward-facing ideology proclaiming a New South. Although most southerners continued to farm, live in rural areas and small towns, and adapt many of their earlier folkways, a sense of change was also a part of southern life. Most notably, the railroad came to symbolize a new freedom of movement and the possibilities of economic development. Developing industries such as textiles, timber, and mining brought southerners off the farms and into new work and business arrangements. Southern religious leaders blessed the wealth that came out of capitalist economic development. Imposing new urban churches began to appear as centers of social prestige, economic power, and cultural authority. Defeat of the southern cause in the Civil War led evangelical Protestants to fear for their future, but their energetic efforts at evangelism and missionary work strengthened their role in southern life by the turn of the twentieth century. While an evangelical worldview had come to characterize much of the South before the Civil War, the postwar period saw rising membership in evangelical churches and participation in church life. The Southern Baptist Convention; the Methodist Episcopal Church, South; and the Presbyterian Church in the United States consolidated their independence as regionally distinctive mainstream churches of the New South.

By the turn of the twentieth century, black church membership was 2.7 million out of a population of 8.3 million, an amazing commitment to churches as the central institutions of southern black life. The Baptists, especially the National Baptist Convention, which had consolidated in 1895, attracted the largest African American membership. The next largest black denomination was the Methodists, embodied in the African Methodist Episcopal church, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church, and the Colored Methodist Episcopal church. Black church doctrine was often similar to that of white evangelical denominations—fundamentalist and biblically centered, otherworldly, fatalistic, and moralistically focused on individual sinfulness. In a racist society, black churches always had the challenge of creating nurturing spaces for their people. Black religion affirmed the equality of the individual, whatever the white society was saying, and the church represented one of the few institutions affirming the ultimate dignity and worth of blacks in the Jim Crow South. Although critics would later deride black preachers as Uncle Toms who assimilated to the caste system, the church provided the base for social dissent and collective protest whenever conditions made it possible in the twentieth-century South. The folk religion of the rural South was at the heart of what W.E.B. DuBois called the “souls of black folk” and would long inspire the musical, literary, and artistic creativity of African Americans (DuBois, 1904).

Sectarian religions, those new religious movements that grew out of dissatisfaction with mainstream churches, burst forth with new manifestations around the turn of the twentieth century. The Churches of Christ, for example, are a Restorationist church, embodying an early New Testament church outlook and local congregational control. Their opposition to musical instruments in worship and to organized missionary societies marked their difference from most southern Protestants, and their strong inheritance of Calvinist theology distinguished them from evangelicals. The Churches of Christ gained early strength in middle and west Tennessee, from where they spread out into influence in hill country regions of the mid-South and into the Southwest. Holiness churches were even more significant, emerging from Methodism as an urgent expression of a religion of the spirit and appealing to the working class and the disfranchised.

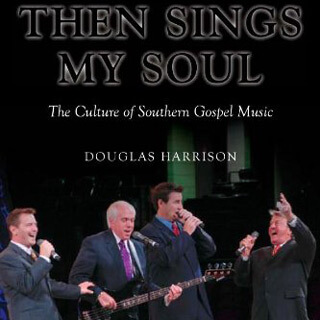

Methodist founder John Wesley had written of a post-conversion second infusion of grace, leading to perfectionism, and Holiness believers stressed this doctrine as a central point of faith. Pentecostalism later emerged out of Holiness, practicing such spiritual manifestations as the baptism of the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues, and faith healing. Pentecostals could be found on the Great Plains and in southern California in the early twentieth century, but eastern Tennessee was one of its hearths as well. A.J. Tomlinson had once been a leader of Holiness members in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee, but he later helped found the Church of God, in Cleveland, Tennessee, one of the most important Pentecostal groups. In 1906 Charles Harrison Mason founded the leading African American Pentecostal group, the Church of God in Christ, in Memphis. Sectarians relied often on charismatic leadership, doctrinaire beliefs, and rigid morality to create separate religious space and to compete effectively for members. The Holiness/Pentecostal tradition—the Sanctified Church in black culture—has been an especially creative force shaping generations of religious and secular music.

In the late nineteenth century, Roman Catholics and Jews entered a new phase of their experience in the South, which lasted until the mid-twentieth century. New immigrants from Italy, Syria, and Lebanon, as well as continued Irish immigration, brought more Catholics into the South at the turn of the twentieth century, although the numbers were far below those in northeastern and midwestern areas. These newcomers energized the church and prompted its efforts to meet their needs. The church worked to preserve a Catholic identity in the South, despite being in an overwhelmingly Protestant culture, through recreational organizations, devotional groups, use of southern-born priests, and especially, parochial schools. The Catholic Church, however, often succumbed to the pressures of the dominant white southern society, even establishing Jim Crow segregation in parishes and schools. Catholics suffered increased harassment in the half century after 1890, and found their political aspirations severely limited.

Anti-Semitism was similarly at its worst in the decades after 1890, and the lynching of Leo Frank in 1915 dramatized the terror that could affect anyone in the South who did not fit the orthodoxies of a closed society. Southern Jews practiced their religion, but they tended to embrace Reform Judaism, with its less restrictive dietary and ritual requirements than Jewish Orthodoxy, making them stand out less from their Protestant neighbors. They sometimes built temples that looked like Protestant churches. Southern evangelicals are people of the Bible, and they often understood the Jews among them as descendants of Old Testament Hebrews. Catholics and Jews became southerners, albeit with differences from the large number of Protestants around them.

Top, The Big Gospel Tent Revival, Shelby, North Carolina, January 1, 2000. Photograph by Flickr user Brittany Randolph. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Bottom, Camp Meeting buildings and tents, James Island, South Carolina, July 4, 2014. Photograph by Flickr user romana klee. Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 2.0.

The church life of Protestants had its own rhythms that reflected and shaped rural and small town life. Religious ties to the southern environment were especially manifest in the common outdoor baptisms in rivers and streams with congregations and onlookers standing witness on the banks nearby. The South remained largely agriculturally based, and a central ritual of evangelicalism, the revival, usually took place in the mid-to-late-summer when crops were in the ground and worshippers could devote their spirits to refreshment. Evangelistic campaigns were major social and cultural activities. Revivalism came out of the predominant concern of evangelicals for conversion of the lost, and revivalists became celebrities. Georgia Methodist Sam Jones, the most famous revivalist of his time, stressed the need for upright moral behavior and preached Prohibition as well as conversion. As more southerners moved to cities, revivalism moved with them, with mass revivals conducted by traveling preachers like Mordecai Ham and J.C. Bishop (the “Yodeling Cowboy Evangelist”) becoming prominent features of urban life. In the late twentieth century, Billy Graham would take evangelistic campaigns out of his native North Carolina into unprecedented international forums.

Modernity was a mixed blessing for southern religious people. They embraced the opportunities it presented for expanding evangelical and outreach projects, through better training for ministers in better-funded educational institutions, larger church facilities to provide more services for their followers, and extended networks made possible by improved transportation and communication. Modern thought, however, raised enormous fears for people rooted in theological and social orthodoxy. Science raised special concerns because of its rising authority in Western Civilization, and scientific evolutionism and higher criticism of the Bible have continued for generations to alienate southern evangelicals committed to a literalist reading of the scriptures. The Scopes Trial, in the summer of 1925, became the most notorious example of seeming southern religious hostility to the forces of modern science leading to the image of the South as the "Bible Belt" to characterize the South and other areas of conservative Protestantism. Despite their theological conservatism, the South’s predominant churches did not provide as strong a home for the national fundamentalist movement as one might have been thought. To be sure, believers who saw themselves as “fundamentalist” fought for control of their denominations in the 1920s, but they lost to moderates. Moreover, southerners kept close allegiance to their sectional denominations, limiting their involvement in interdenominational national fundamentalist agencies. After the Scopes Trial, fundamentalism as an organized movement did slowly mature in the South, embodied in private educational institutions, independent associations, and interdenominational groups.

Reform and Reaction in Sectional Religion, 1940–2000

World War II brought more change to the US South than any other event in its history, even the legendary Civil War. The World War upset traditional patterns of thought and behavior, exposing southerners to new ways of thinking, and it launched economic developments that would overcome the long period era of poverty. It opened a new period in which the South experienced fundamental changes in a social system that had long shaped ideology and experience. Changes in communication and transportation, population growth, urbanization, the end of the one-party political system, consumerism, secularization — all pushed the South toward change. Yet the South retained a self-consciousness promoted by new national acceptance of cultural identities of all shapes, by appreciation of southern cultural traditions by a concern for tourism, by nostalgia, and by the functionality of southern organizations within a national federalist framework. Black southerners became among the most energetic examiners of the mythology of the white South, as well as of their own self-consciousness as southerners. Appreciation of regions within the South has also grown, seen in the emergence of new conceptualizations of those regions, such as the Mid-South around Memphis, Tennessee; a central Texas complex within the larger, traditional Southwestern region; the Atlanta metro region; and a central Florida region anchored by the fantasies of Disney World. Through all the changes, the traditionally-dominant denominations have retained their hold. While a force for spiritual normalcy and often disengagement from the public sphere, religion has also been deeply involved in both liberal and conservative political crusades.

The civil rights movement was a central moral landmark for the South. African American church leaders, such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Fred Shuttlesworth, and Ralph David Abernathy, emerged as the leading edge of reform, and local congregations provided the foot soldiers for the movement’s nonviolent protests and boycotts. The protests drew from principles of nonviolence that King learned from Indian leader Mahatmas Gandhi, but equally significant sources were Christian teachings on social justice and the heritage of the southern black church’s witness against the evils of segregation. The civil rights movement made the end of Jim Crow segregation a compelling moral challenge to the white South. In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. the Board of Education decision, major southern white denominational leaders and regional meetings counseled compliance with the call for desegregation, but most rank-and-file church members rebelled, rejecting the social changes that loomed. Some ministers used the same biblical justifications for segregation as their ancestors had used to justify slavery. Progressive clergymen who advocated acceptance of integration often lost their pulpits; ministers who ignored the issue risked moral irrelevancy. Few white religious leaders came out forcefully against the Jim Crow system. In the end, white church people reluctantly acquiesced to racial change, although their segregated churches and private schools remained retreats from those changes. Traditions of separate black and white worship were deeply held and reflected differing worship styles as well as racial divisions. Southern clergy have been among the leaders of racial reconciliation efforts in the recent South, often working through community groups to promote principles of Christian fellowship across social boundaries.

President Jimmy Carter addressing the Southern Baptist Convention, Atlanta, Georgia, June 16, 1978. Photograph by White House staff photographers. Courtesy of The National Archives, archives identifier 17897.

The traditional evangelical denominations, the Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians, have long been at the heart of the South's religious culture, and they retained their hold during this period of social change. Baptists continue to represent about half of the church-affiliated population of the South, Methodists about a quarter, and Presbyterians ten percent. The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) has been a "folk religion of the South," and yet it has also been the largest US Protestant church, thanks in part to establishing new congregations in the West, far beyond the original southern borders of the denomination in the nineteenth century. Increasingly a corporate-dominated bureaucracy, the SBC has long been closely allied with the South’s power structure, lending its conservative voice to issues of racial and social justice. Fundamentalists have taken over institutional control of the denomination since the 1980s, establishing creeds for the enforcement of orthodoxy, reshaping its educational institutions to narrow the range of teaching options, emphasizing the primacy of the inerrancy of the Bible, and moving away from traditional Baptist support for separation of church and state to support, among other government-enforced social causes, prayer in schools. Many moderates have left the SBC, weakening its numerical strength and leaving a narrow ideologically focused, leadership.

Methodists and Presbyterians also remain dominant church traditions in the contemporary South. Southern Methodists rejoined Methodists from other parts of the nation in a 1939 merger, and in 1968 the Evangelical United Brethren joined with them to form the United Methodist church. Methodists in the South represent about a quarter of the national membership. Unlike Baptists, Methodists have retained their Wesleyan stress on piety above creed. Southern Presbyterians have undergone more recent dramatic denominational change than Methodists, having reunited with their northern coreligionists in 1983. Conservatives had already broken away to form the Presbyterian Church in America because of their fears over the liberalism of mainstream southern Presbyterians, fears only confirmed by the national merger.

Black Christianity has also remained a powerful spiritual force in the latest South. The clerical role in leading the civil rights movement gave churches considerable moral authority, buttressing their historic and continuing efforts in providing fellowship, social services, recreation, sanctuary from the larger society, and a gospel of hope to oppressed people. They have long given a prophetic dimension that few other religious institutions have provided. The National Baptist Convention remains the largest black Baptist group, and the African Methodist Episcopal church is the leading black Methodist body. The movement for a specifically black theology has also had its adherents in the South, dating back to the call for black power in the late 1960s. African American ministers within predominantly white denominations particularly championed black theology as a sometimes militant demand for true spiritual integration. The United Methodist church struggled into the 1970s to desegregate the central jurisdiction into the church’s overall ecclesiastical system, and its failure to adequately do so allowed black Methodist clergymen to exploit the guilt and moral indecisions of white Methodists.

Secularization slowly loosened the hold of religious ideology upon public morals. The new right political movement that began in the 1980s with the Moral Majority saw the rise of the Religious Roundtable and the Christian Coalition, and received a new boost through the presidency of George W. Bush, has attempted to address this slippage. While a national movement, the religious right hopes to impose on society and church institutions a discipline that adherents believe once existed in the small towns and rural society of the earlier South before becoming besieged in the dramatic social changes of the 1960s. The religious right aims to anchor the nation’s political direction in a moral outlook grounded in its biblical interpretation. National leaders of the movement have included many southern figures, such as Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Ralph Reed, and Oral Roberts. The religious right engages those issues it sees as part of an agenda of “traditional values,” including issues related to family definition, as well as abortion, pornography, prayer in schools, and before its defeat, the Equal Rights Amendment. Concern for prohibition of the sale, or even consumption, of alcoholic beverages is not a part of this political agenda, a major departure from the traditional southern ethics of the churches. The new agenda represents, then, a continued belief that fundamentalist, evangelical churches must impose their moral code upon a society in need of discipline.

Religion continues to define the US South as a distinctive part of the United States. It contributes to defining debates on public policy issues and provides on-going organizational bases for political campaigns across the ideological spectrum. It supports a needed infrastructure of social services and educational institutions in southern regions where public agencies are underfunded. It offers a still compelling worldview to the majority of the South’s Christians, giving meaning in troubled times and empowering the poor and marginalized. Southern religion has supported a peculiar variety of religious pluralism within the United States, allowing for religious minorities to flourish. Forms of religion identified with the South—evangelicalism, fundamentalism, pentecostalism—have traveled throughout the nation, a prime example of the “southernization of the United States.” Meanwhile, southerners themselves live in places that often cannot be seen as southern so much as parts of a national or even global network. Recent immigration, especially the arrival of Hispanics in record numbers, has increased the Roman Catholic role in the South. Americans moving southward since the 1970s have brought denominations and traditions once seldom seen in the South, adding to its religious diversity.

About the Author

Charles Reagan Wilson is director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi in Oxford. A professor of history and southern studies, he earned his BA and MA at the University of Texas in El Paso and his PhD at the University of Texas in Austin. His books on southern religious and cultural history include Judgment and Grace in Dixie: Southern Faiths from Faulkner to Elvis (1995) and Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1868–1920 (1980). In addition, he edited The New Regionalism (1997) and Religion in the South (1985), and co-edited Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (1989) and Religion and the American Civil War (1998).

Publication History and Update

In Fall 2015, Southern Spaces updated this publication as part of the journal's redesign and migration to Drupal 7. Updates include a full collection of new images and text links, as well as revised recommended resources and related publications. For access to the original layout, paste this publication's url into the Internet Archive: Wayback Machine and view any version of the piece that predates October 2015.

Cover Image Attribution:

Megachurch worship, Lakewood Church, Houston, Texas, January 12, 2008. Photograph by Flickr user aJ Gazmen. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.Recommended Resources

Ammerman, Nancy Tatom. Baptist Battles: Social Change and Religious Conflict in the Southern Baptist Convention. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990.

Anderson, Jon W. and Friend, William eds. The Culture of Bible Belt Catholics. New York: Paulist Press, 1995.

Boles, John B. The Great Revival, 1787–1805: The Origins of the Southern Evangelical Mind. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1972.

DuBois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches. Chicago: A.C. McClung, 1904.

Eighmy, John Lee. Churches in Cultural Captivity: A History of the Social Attitudes of Southern Baptists. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1972.

Frey, Sylvia T. and Betty Wood. Come Shouting to Zion: African-American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Glass, William R. Strangers in Zion: Fundamentalists in the South, 1900–1950. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2001.

Gwynn, Frederick L. and Blotner, Joseph L., eds. Faulkner in the University: Class Conferences at the University of Virginia, 1957-58. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1959.

Harvey, Paul. Freedom's Coming: Religious Culture and the Shaping of the South from the Civil War through the Civil Rights Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Heyrman, Christine Leigh. Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Women's Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Hill, Samuel S, Jr., ed. Encyclopedia of Religion in the South. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1984.

Hill, Samuel S., Jr. Southern Churches in Crisis. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1967.

Isaac, Rhys. The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

Larson, Edward J. Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate over Science and Religion. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

McLoughlin, William. Cherokees and Missionaries, 1789–1839. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984.

Manis, Andrew M. A Fire You Can't Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham's Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

Marsh, Charles. God's Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Mathews, Donald G. Religion in the Old South. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Miller, Randall M. and Wakelyn, Jon L., eds. Catholics in the Old South. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1983.

Miller, Randall, Stout, Harry S., and Charles Reagan Wilson, eds. Religion and the American Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Montgomery, William E. Under Their Own Vine and Fig Tree: The African-American Church in the South, 1865–1900. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

Newman, Mark. Getting Right with God: Southern Baptists and Desegregation, 1945-1995. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.

Ownby, Ted. Subduing Satan: Religion, Recreation, and Manhood in the Rural South, 1865-1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Raboteau Albert J. Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Schweiger, Beth Barton. The Gospel Working Up: Progress and the Pulpit in Nineteenth-Century Virginia. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Snay, Mitchell. The Gospel of Disunion: Religion and Separatism in the Antebellum South. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Stowell, Daniel. Rebuilding Zion: The Religious Reconstruction of the South, 1863-1877. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Tweed, Thomas A. "Our Lady of Guadeloupe Visits the Confederate Memorial," In Southern Cultures, 72-93. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Wacker, Grant. Heaven Below: Early Pentecostals and American Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Wilson, Charles Reagan. Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980.

Wilson, Charles Reagan. Judgment and Grace in Dixie: Southern Faiths from Faulkner to Elvis. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.