How the Discovery of Two Lost Ships Solved an Arctic Mystery

The Franklin expedition and all its crew disappeared in 1848.

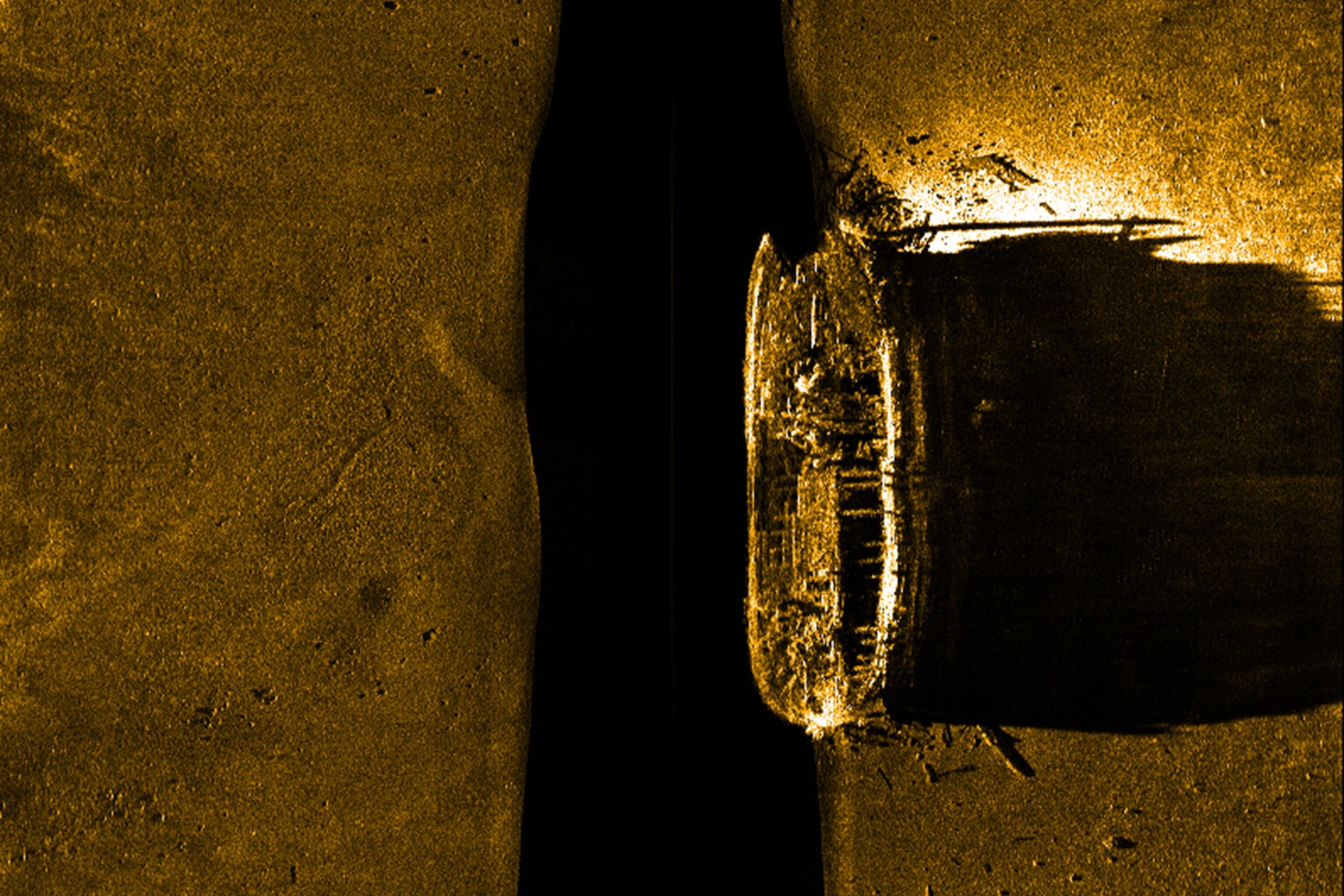

In 1848, the Franklin expedition’s two ships, H.M.S. Erebus and H.M.S. Terror, disappeared with all their crew while searching for the Northwest Passage. Their fate is one of the enduring mysteries of the age of exploration. Numerous expeditions were sent out to find them, numerous theories proposed to explain what happened. Dark rumors of cannibalism only made the mystery more compelling. It wasn’t until 2014 that a Canadian mission, equipped with all the latest marine archaeological equipment, located Erebus. Terror was discovered two years later.

Paul Watson, author of Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition, was on board the lead Canadian vessel when Erebus was found. Speaking from Vancouver, Watson explains why the hunt for lost historic ships was a geopolitical move against Russia, how Lady Jane Franklin combined politics and spiritualism to find her missing husband, and why the Inuit want Sir John Franklin’s body located and sent back to England.

Franklin disappeared in 1848 while searching for the Northwest Passage. Set the scene for us.

In 1845, Franklin was about to turn 60. He had had a terrible time as governor of what was then called Van Diemen’s Land, now Tasmania, where he was politically stabbed in the back and recalled to England by the colonial office, his reputation in tatters. His wife, Lady Jane Franklin, an extraordinary woman, was determined to help him rehabilitate his image and his career. How do you do that? You go back to where you became a hero, and that is the Arctic.

This was his fourth Arctic expedition, his third as commander. He had almost starved to death on an overland expedition, and became known in the press as “the man who ate his boots” because he ate his shoe leather to get out of the Arctic alive. He was an extraordinarily heroic figure but tarnished by politics. So his wife Jane lobbied and begged for him to be sent on one last expedition.

The last time the expedition was seen was as they’re entering Lancaster Sound, which is the eastern entrance of what we now know as the Northwest Passage. His instructions were to sail north. But they ran into ice so came south again. On his way south, he ran into an ice trap—and was never heard of again.

Back in London, Franklin’s intrepid wife Jane begins a campaign for what you call “the longest, broadest and most expensive search for two lost ships in maritime history.” Tell us about this extraordinary woman—and how she mobilized public opinion.

The descriptions of her as a girl are that she was extremely shy. But when she has to deal with Sir John’s disappearance, she’s far from shy. She takes the Admiralty and various other institutions in her way and simply bowls over them. She even took an apartment near the Admiralty building in London so she could watch the comings and goings. She would also hold meetings in that apartment, which was known as “the fortress,” where former explorers and experts would roll out maps of the Arctic.

The Admiralty kept saying, “They have enough food for three years. So we don’t need to worry until at least 1848.” She kept insisting that they search and even began to fund her own expeditions. She even wrote to Zachary Taylor, the president of the United States. It’s an extraordinary letter coming from a woman who has broken protocol by writing as a citizen from London, not through diplomatic channels. Through all of this extraordinary effort and the help of others, including Charles Dickens, she forces the Admiralty to send out search expeditions.

Franklin’s disappearance became what we today call a media circus. It also took a weird detour into the paranormal, didn’t it?

That’s where I got hooked. Among Lady Jane’s nearly two hundred journals and two thousand letters are some that describe her dabbling in the paranormal, going to seers and clairvoyants, to connect to her husband. She was eventually contacted by a Captain William Coppin, a wealthy shipbuilder from Londonderry, Ireland. His daughter Louisa, who was known as “Little Weesy,” died in the summer of 1849. While he was away on business for three months, his children said Weesy was always around. Their description was not like a ghost we would imagine from films but a hovering blue light. Weesy’s brother would see it and run and smash his face against the wall, causing his face to bleed. The children were convinced they were communicating with the ghost of Weesy. One day, Weesy’s aunt said to her daughter, “Why don’t you ask Weesy if she knows where Sir John Franklin is?”

One of the key figures in the modern hunt for Franklin is an Inuit named Louie Kamookak. Talk us through the Inuit stories about Franklin and Louie’s contribution to the final discovery.

As a child, Louie Kamookak heard a story from a woman named Humahuk, who describes going as a girl with her father and discovering some items. One was a knife, which Kamookak thinks from her description was probably a butter knife. She also finds what appeared to be rabbit droppings but was likely the shot for Royal Navy rifles.

That story stayed in Louie’s mind and he became determined to try and figure out where that place was. Eventually, he came to understand that the story was connected to the Franklin expedition. As an adult, he did research into Inuit oral history. As he went around talking to people, he realized he could perhaps also answer some of the mysteries about the Franklin expedition.

This is a key turning point in the modern search because in these converging lines of fate, while he’s doing his research, experts in archaeology and history are also doing theirs. Eventually, the two meet and that is when the pace starts to pick up. If you take Inuit oral history and combine it with modern science, that’s when the breakthrough comes.

Let’s fast forward to 2014 and the Canadian government’s Victoria Strait Expedition. There was a political dimension, wasn’t there?

A lot of the story in Ice Ghosts harks back to the 19th century. Geopolitics is a central part of it. At that time, the Royal Navy was supreme. They believed if they didn’t find the Northwest Passage someone else would, and they meant the Russians. Flash forward to the 21st century, and the Arctic is still about competition between Russia and the West. In 2007, the Russians took a titanium flag and, using a remotely operated sub, planted it on the seabed near the North Pole, in a part of the high Arctic where there are competing claims.

This sent a shiver through the Canadian political establishment. So in 2008 Stephen Harper, the Conservative prime minister, decided to launch a new search for the lost Franklin ships. It was a crafty way of packaging a political agenda with the shiny wrapping of an adventure that speaks to the heart of Canadian nationalism.

Harper demanded strict control over all federal science. So when the 2014 expedition found H.M.S Erebus, it was the best-kept secret in Canada. No one was allowed to tell even the captain of the Coast Guard icebreaker, the lead vessel on the expedition, until they had gone through a step-by-step protocol notifying federal officials up the line, all the way to the prime minister. It was several days after the discovery that I found out, even though I was living aboard the Coast Guard vessel and was a cabin mate with the head of the Parks Canada marine archaeology team, the first people to set eyes on the wreck.

H.M.S Erebus was discovered in relatively shallow water and almost perfectly preserved, except for the stern, which had been bitten away, probably by ice. The stern is important because that’s where Franklin’s cabin was. Inuit stories dating back to the period shortly after the ships were abandoned speak of Inuit boarding one of the vessels and finding a large man seated in a dark room, obviously dead, with a huge grin on his face. Experts suspect this was the rictus grin you see on a corpse as the lips and gums recede. Because so much else of what they describe of the location and the ship itself has turned out to be correct, the possibility that there actually was a dead man in the cabin of H.M.S. Erebus is an intriguing possibility.

We know that Franklin died on board because a note was found saying he died before the ships were abandoned. Whether it was Franklin that was described as dead, sitting in a dark room, nobody knows. But it is certainly a possibility.

A final “mystery within a mystery,” as Louie Kamookak calls it, remains: the location of Franklin’s grave. What do we know about it—and why is it so important to Louie to find it?

It’s anyone’s guess whether Franklin is, in fact, buried up there. But Louie certainly believes he is. He told me that he was never just interested in finding the ships. What he wanted to find was Franklin’s grave.

There are stories about a cairn-like structure with a big, flat top. Inuit also described a kind of liquid rock, which sounds like a rudimentary cement. With someone of Franklin’s stature, you would want to build a tomb to preserve him, so that you could come back later and take him home to bury at Westminster Abbey, or something. There are also descriptions of what sounds like a rifle salute, which you would expect for the funeral of a high-ranking person like Sir John. The wonderful thing, if they do in fact find a grave, is that there might be some documents in there, which may answer more questions about what happened.

There is also a spiritual dimension. Louie and other Inuit believe that King William Island has been cursed ever since Franklin’s expedition ran into trouble and everyone aboard died. What Louie told me is that he seeks peace for himself, for his people, and for the land. If he can find Franklin, and send him home, that peace will come. The disturbed spirits, which have caused so much trouble for his people, will be silent.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security

History & Culture

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

Science

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

Travel

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park

- Spend a night at the museum at these 7 spots around the worldSpend a night at the museum at these 7 spots around the world