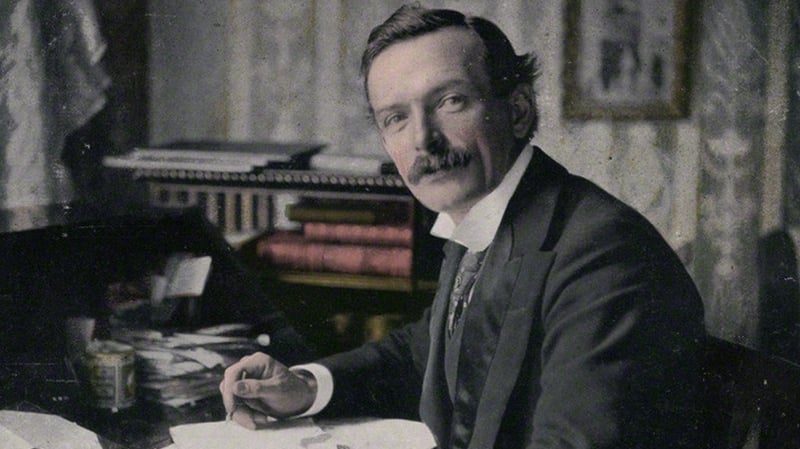

She was the radical who was hailed as one of the most beautiful women in the world, and now she's one of the subjects of a new documentary, Forgotten: The Widows of the Irish Revolution, which you can watch here. In this entry from the Royal Irish Academy's Dictionary of Irish Biography, Margaret O'Callaghan & Caoimhe Nic Dháibhéid tell the story of Maud Gonne Mac Bride.

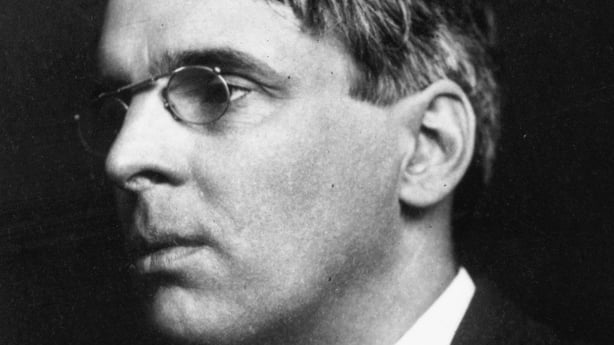

(Edith) Maud Gonne MacBride (1866–1953), advanced nationalist, political activist, and subject of most of the love poetry of W. B. Yeats, was born 21 December 1866 at Tongham Manor, near Farnham, Surrey, England, eldest daughter of Captain Thomas Gonne (1835–86) of the 17th Lancers and his wife, Edith Frith Cook (1844–71). Her father's family were wealthy importers of Portuguese wines. Maud later claimed that their origin was Irish, and produced some paperwork to prove it. The Cooks were prosperous London drapers. Both families were of considerable social standing.

Childhood and nationalism

In April 1868, at a time of high government alarm regarding the Fenian threat, Thomas Gonne was appointed brigade major of the cavalry in Ireland and was stationed at the Curragh military camp in Co. Kildare. Maud's sister Kathleen Gonne (d. 1919) was born in September 1868. The family seem to have lived at Airfield, near Donnybrook, south Dublin. Their neighbours were the Jamesons, the distilling family, whose daughter Ida was Maud's friend.

Edith Gonne, suffering from tuberculosis, gave birth in London to her third child, Margaretta, in June 1871; she died and the child died some months later. Tuberculosis was to shadow Maud and her sister Kathleen for most of their lives.

The family returned to Ireland, and the children and their nurse were moved first to the Curragh and then to a cottage on Howth Head, Co. Dublin, for health reasons. Howth remained a sacred place for Maud.

When Maud was six this idyll ended: she and Kathleen were sent to live with her mother's aunt, Augusta Tarlton, at 24 Hyde Park Gardens, London, and from there to Augusta's brother Francis Cook at Doughty House in Richmond Park, which housed the family art collection, including works by Velasquez and Van Eyck. In 1876 Major Gonne was appointed military attaché to the Austrian court, and the family left for the south of France. For the rest of her life Maud was as comfortable in France as in Ireland or England, and was as fluent in French as in English.

Returning from a position in India in 1879, Thomas Gonne travelled around Europe with Maud till he was posted to Dublin as assistant adjutant-general at Dublin castle in 1882. Maud claimed to have reserved seats at the window of the Kildare Street Club to see the state entry of the new lord lieutenant on Saturday 6 May 1882, the fateful date on which the Phoenix Park murders took place.

She seems to have kept the season of 1886 at Dublin castle; the season began with the levee after Christmas and reached its highlight with the attendance of the prince of Wales at the St Patrick's night ball. This period is described by Gonne in her 1938 memoir A Servant of the Queen, one of the many texts through which she is mythologised, in this instance by herself.

By 1886 Maud Gonne had become a nationalist; she claimed to have recited Emmet's oration, from The Spirit of the Nation (1845), at a public dinner at which her father was present. She spent time in France and Germany with her great-aunt Mary, widow of the Comte de Sizeranne, who hoped to launch her as a professional beauty. Colonel Gonne intervened and took her to Bayreuth for the Wagner festival.

According to Maud, on their return to Dublin, he told her that he would resign his commission and become a home rule MP, apparently identifying with her horror at evictions they had both witnessed. She appears to have been in Dublin from January 1885 to November 1886, perhaps with intervals on the Continent . Colonel Gonne died on 30 November 1886 from typhoid fever, leaving both of his daughters orphans.

Maud and Kathleen Gonne spent an unhappy time in London under the guardianship of their uncle William Gonne. Unaware that she would inherit a fortune on her majority, Maud Gonne tried to become an actress, but became ill with the tuberculosis that stayed with her throughout her life; in the summer of 1887 she went to the French spa town of Royat in the Auvergne to recover.

Here she met Lucien Millevoye (1850–1918), a married journalist with fervid right-wing politics, a supporter of General Boulanger, and a revanchist, later a deputé. Millevoye was sixteen years older than Maud; at the age of 20 she seems to have begun a passionate affair with him within a year of her father's death.

Financial independence and political activism

In December 1887 Maud Gonne inherited trust funds in excess of £13,000 and an unentailed sum from her mother's estate. She was a very wealthy woman and was free to live as she pleased. She travelled early in 1888 on a clandestine Boulangist mission (of which we have a contemporaneous account by Princess Catherine Radziwill) to Russia, where she met the notable Pall Mall Gazette editor W. T. Stead, who wrote of meeting in St Petersburg 'one of the most beautiful women of the world' (Review of Reviews, 7 June 1892).

Her relationship with Millevoye was both sexually and politically driven; he would redeem France by regaining Alsace-Lorraine, her mission was Ireland, and together they constituted an alliance against the British empire. Her sense of self was one in which the personal and the political were fused.

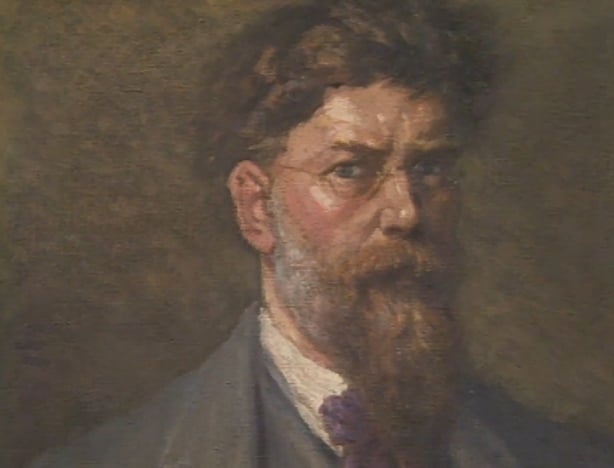

She returned to Dublin later in 1888, where Sarah Purser painted her portrait, which she hated. Staying first with the Jamesons at their house ‘Airfield’, she soon established herself in an apartment over Morrow's bookshop in Nassau St.

Unconventional

Her independence was highly unconventional in the Dublin of that time. With Ida Jameson, daughter of a staunchly unionist family, she exchanged rings on which ‘Éire’ was inscribed, as a testament to their shared commitment to home rule. Together they arranged to meet the Trinity academic and home ruler Charles Hubert Oldham, and they were both invited by him to the meetings of the Contemporary Club at 116 Grafton St.

She soon established herself in nationalist circles, becoming a friend of the old Fenian John O'Leary and his sister Ellen, and a friend too of Dr George Sigerson, J. F. Taylor, T. W. Rolleston, George Russell, and Stephen Gwynn. She spent much of her time at the O'Leary house in Rathmines, consulting the canonical texts of the nineteenth-century written nationalist tradition.

Gwynn wrote years later:

‘Since she was by our standards rich and immensely tall, and of the most surpassing beauty, there was a buzz of gossip, through which she moved, amused rather than indifferent’.

Douglas Hyde wrote in his diary on 16 December 1888:

‘to Sigersons in the evening where I saw the most dazzling woman I have ever seen: Miss Gonne who drew every male in the room around her . . . We stayed talking until 1.30 a.m. My head was spinning with her beauty’.

On 30 January 1889 she met William Butler Yeats in London, having been given an introduction by John O'Leary.

Maud Gonne's great beauty stunned Yeats – tall, bronze-haired, bronze-eyed, and with a 'complexion . . . luminous, like that of apple-blossom through which the light falls'. He loved her with an unrequited passion thereafter. He wrote overtly about her in over fifty poems, though arguably her presence pervades all of his work. They engaged on the ground of theosophy, the spirit world, and Irish nationalism.

On 11 January 1890 in Paris, where she had an apartment at 61 Avenue Wagram, Maud gave birth to a son. She was just 23. Millevoye was the father and they named the boy Georges Sylvère. She had sufficient means and resourcefulness to keep the child, though she never spoke of him to her Dublin circle. He belonged to the French part of her life.

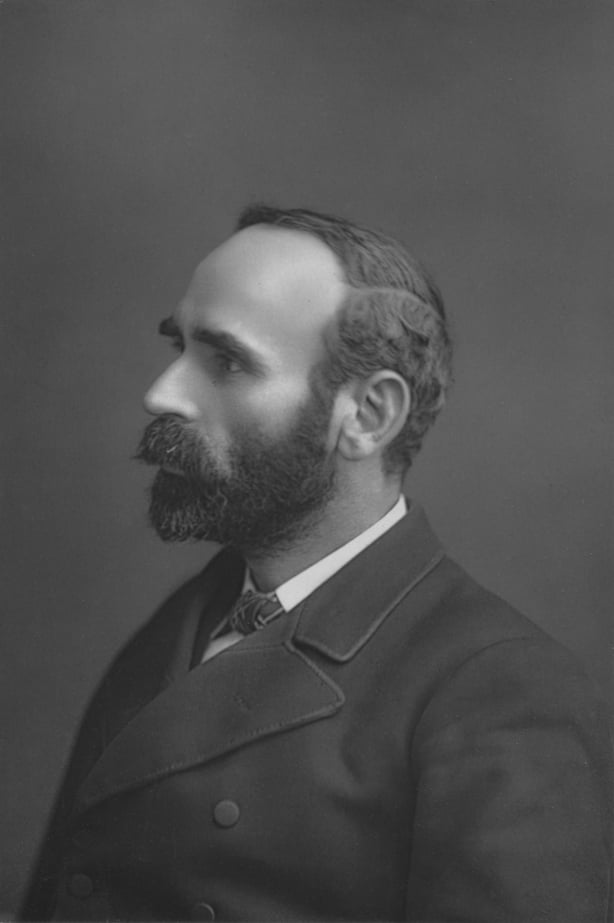

Both before and after the birth of her child she was involved with the Plan of Campaign in Donegal and other locations, and in amnesty campaigns in Britain, much to O'Leary's disquiet. She had earlier secured introductions to Michael Davitt, who was suspicious of her, and to Timothy Harrington, who saw her propaganda potential and gave her introductions to key figures in the Plan of Campaign disputes in Co. Donegal.

She took her cousin and close friend May Gonne and her giant dog Dagda with her in 1890 to the Olphert estate in Falcarragh, where she dined with the bishop and parish priests, and galvanised local opinion.

Although she was refused membership of the Celtic Literary Society, the National League, and the IRB on the grounds of her gender, she largely stood outside the rules for other women of her generation, marked out as free by her beauty, her wealth, her style, and her passions.

She campaigned with Harrington on the electoral platform for the home rule candidate D. Duncan at Barrow-in-Furness, Lancashire, in June 1890. She lectured on the horrors of eviction to English audiences, and visited long-term Fenian prisoners in Portland jail. Yeats spoke of her as ‘the new Speranza'.

Fragile health

The daily grind of campaigning did, however, affect her always fragile health. George Sigerson was her Dublin physician, although she seems to have rejected his regime for dealing with consumption, while cooperating with him in arranging for the publication of Ellen O'Leary's poems. She went to the south of France to recover and to spend time with Millevoye – and with her child.

In 1891 Maud Gonne spent part of the summer in Ireland in the company of Yeats but was called back to Paris, where her child was seriously ill. Georges Gonne died, apparently of meningitis, on 31 August 1891 and she wrote Yeats a letter of ‘wild sorrow’ telling him that an ‘adopted’ child had died.

By a strange coincidence, she travelled back to Dublin on 11 October, on the boat to Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire) that carried Parnell's coffin home; she was wearing deep mourning for her son, and it was believed that she was theatrically grieving the lost leader.

Yeats and Maud Gonne were possibly briefly engaged, they were certainly very closely together, and in November 1891 she was initiated into the Order of the Golden Dawn in London. Her political leanings were complicated. She was moulded by her right-wing Boulangist associates and shared in their anti-Semitic and anti-masonic conspiracy theories; under Millevoye's influence she became a vehement anti-Dreyfusard.

A strong supporter of the Amnesty Association of Great Britain, she moved between Dublin, London, and Paris but also lectured in provincial France, Holland, and Belgium on the plight of evicted tenants in Donegal. She published ‘Un peuple opprimé’ in La Nouvelle Revue Internationale and also published a series entitled ‘Le martyre de l'Irlande’ for the Journal des Voyages. She cooperated with Yeats in the National Literary Society and attended its inaugural meeting in 1892.

In 1893, hoping to reincarnate their dead child, Maud Gonne and Millevoye had intercourse in the crypt of the mausoleum which she had built for Georges. The birth of her daughter Iseult Gonne in Paris on 6 August 1894 ended Maud's sexual relationship with Millevoye. She remained politically associated with him, however, and when he became editor of La Patrie he published many of her articles.

After her pregnancy she rapidly returned to work for various nationalist and political organisations, notably the Amnesty Association, and became aware, through her frequent travels back to Ireland, of the new radical nationalist Belfast journal published by Alice Milligan and Anna Johnston (‘Ethna Carbery’) as the Shan Van Vocht. In May 1897 she started her own journal, L'Irlande Libre, to present the Irish cause to continental Europe, and also formed L'Association Irlandaise, the Paris branch of the Young Ireland Society.

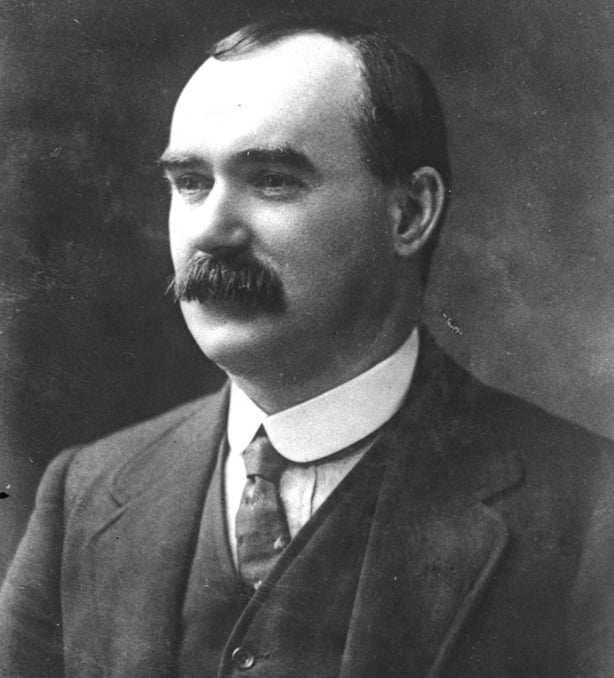

Her activities brought her into the sphere of James Connolly, in whose company she spoke from the platform of a socialist meeting on 20 June 1897, after a torchlight procession through the streets of Dublin headed by a hearse, the coffin inscribed ‘The British empire’.

From October to December 1897 she toured the US to raise funds for the Amnesty Association and for the Wolfe Tone memorial. On her return she threw herself into the 1798 centenary commemorations with Yeats and John O'Leary. This commemoration was one of the key events in which the new nationalism drove and sought to set the agenda for the established parliamentary nationalism over the next few years.

Fighting for tenants

Parallel with public meetings about the renewal of the spirit of ‘98, Gonne became involved with the plight of the poorer tenants of the west. At public meetings in Mayo she attacked the government, building on anti-jubilee rhetoric of Victoria as ‘the famine queen’. With James Connolly again she wrote and distributed The Rights of Life and the Rights of Property. This was her most intense period of sustained political activity.

Impressed by the Shan Van Vocht, she supported her close friend Arthur Griffith and his associate William Rooney in the early stages of their new newspaper, the United Irishman. Arising out of the commemorations, the paper built itself up on the pre-existing subscription list of the Shan Van Vocht, and Gonne provided Griffith with financial as well as emotional support in the endeavour. She also contributed many written articles, the most significant of which was ‘The famine queen'.

At the end of that year she told Yeats the truth about her relationship with Millevoye, and about her two children. She brought Iseult up in France, but did not publicly acknowledge her as her daughter; such an admission would have socially and politically destroyed her. Both she and Yeats dreamed of an astral marriage according to the rites of their shared beliefs, but she refused to marry him in the material world.

She travelled to Belfast with Yeats in September 1899 and met Alice Milligan and the former Shan Van Vocht circle there (the paper had ceased to appear in April 1899). Later that year she and Arthur Griffith founded the Transvaal committee to support the Boers in their war with Britain. This committee encouraged recruitment to the ‘Irish Brigade’, largely composed of advanced nationalists and republicans fighting on the side of the Boers against the British empire. This brigade was effectively led by Major John MacBride, who gained a heroic reputation.

In January 1900 Maud went on a second tour of the US, supporting the stance of the Boers, and collecting funds for Griffith's paper. The main event of that year was the protest against the queen's visit on 4 April. In opposition to the public celebration of the visit with a children's party and free food in the Phoenix Park, Maud Gonne organised a patriotic children's picnic in July. This led later to the extension of the provision of free meals to poor children to Ireland, when she enlisted the help of Stephen Gwynn.

Inghinidhe na hÉireann

On Easter Sunday 1900 she founded Inghinidhe na hÉireann, an advanced nationalist women's movement, later an affiliated organisation to Cumann na nGaedheal which was launched by Griffith and Rooney the following October. She also successfully sued Le Figaro for alleging that she was a British spy.

In the winter of 1900 she met MacBride at the Gare de Lyon; he was returning from the Transvaal to exile in Paris. They toured the US together in 1901 and again in 1902. On her return she travelled around the country setting up branches of Inghinidhe (or ‘the ninnies’, as they were popularly known).

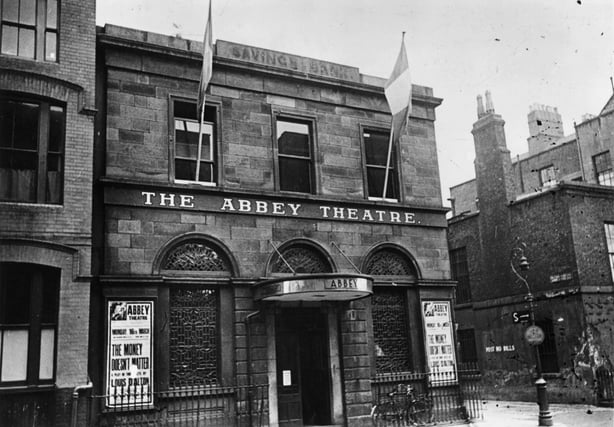

On 2 April 1902 she performed the lead in Yeats's play ‘Cathleen Ni Houlihan’. This play represented the high zenith of Yeatsian revolutionary fervour, and Maud was the embodiment of an Ireland that demanded the blood of her sons. Some months later she decided to marry MacBride, whom she thought vital and honourable; their respective later accounts of their courtship do not tally, perhaps unsurprisingly.

Marriage and its fallout, 1903-1916

Yeats begged her not to marry MacBride, as did Arthur Griffith, who was close to both of them. Undeterred by this and the opposition of both their families, Maud converted to Catholicism on 17 February 1903 and married MacBride on 21 February in Paris.

It seems that from shortly after her marriage she believed herself to have made a mistake. It is clear from later written material by John MacBride that her bohemianism was alien to his style, and that he expected her to cast aside considerable aspects of her past. An indication of the growing distance between the couple is the increasing amounts of time Maud spent in Ireland, where MacBride could not risk a return.

In the summer of 1903 she coordinated Inghinidhe protests around the visit of Edward VII, culminating in the celebrated ‘battle of Coulson Avenue’, where, in mourning the death of Pope Leo XIII, Maud flew a series of black petticoats from her home in defiance of the festive atmosphere of official Dublin.

In October 1903 Maud joined Griffith in nationalist protests against ‘The Shadow of the Glen’ by J. M. Synge, decrying what she saw as the ‘insidious and destructive tyranny of foreign influence’ within the play. She returned to Paris that winter; her second son Seán (Seaghan) MacBride was born there on 26 January 1904.

A definitive break

Towards the end of that year a definitive break occurred between the MacBrides, and Maud initiated divorce proceedings, confessing to Yeats her disgust with ‘a hero I had made’. In the remarkably bitter separation, Maud Gonne claimed that MacBride, quite apart from being drunken, feckless, and uncongenial, had sexually assaulted 10-year-old Iseult, and that relations between MacBride and Eileen Wilson (1886–1972), Maud's illegitimate half-sister, were improper before Eileen's marriage to his elder brother, Joseph.

She also produced sworn evidence from members of her household that suggested sexual assaults on others, and drunken behaviour with an unseemly social circle. In a widely reported case she eventually succeeded (8 August 1906) in obtaining a legal separation and custody of Seán. James Joyce, writing to his brother Stanislaus Joyce on 15 March 1905, said

‘I have read in the Figaro of the divorce of the Irish Joan of Arc from her husband. Pius the Tenth, I suppose, will alter Catholic regulations to suit the case . . .’.

The question of an annulment never seems to have arisen. MacBride's subsequent pursuit of a libel action against the Irish Independent benefited him little financially, or in terms of child custody, but ensured that the case was even more high-profile than it might otherwise have been in Dublin.

The scandal ruinously damaged her position in nationalist circles. In 1906 she was hissed in the Abbey Theatre: a mere four years earlier she had been rapturously received in 'Cathleen Ni Houlihan'. She was never again to be at the centre of advanced politics as she had been in that period from the early 1890s to the end of 1903.

Karen Steele has demonstrated convincingly her centrality to advanced nationalist circles in these years, and in so doing has built on the pioneering work of Margaret Ward. As Padraic Colum wrote at the time, discussing the impact of her removal on Griffith,

‘Maud Gonne's marriage has removed not only an inspiring figure, not only one who brought something of the great world to him, but one who kept him close to notable people . . . The group of intellectuals whom he had mingled with at Maud Gonne's reunions in Nassau St. were dispersed or were no longer on good terms with him’.

In marrying MacBride, whom she does not seem to have passionately loved, she seriously miscalculated. She paid a very high price in terms of almost complete exile from Ireland. She had now considerable forces massed against her, including John O'Leary.

An attempt by R. Barry O'Brien at mediation between herself and MacBride reveals a representative view of Maud as merely wife and mother; as a failed wife, her public space was forfeit. She could very easily have lost custody of her child; the mystique that had protected her from the usual social attitudes towards women had been removed by the separation and her public motherhood.

When she next entered politics after 1916 it was as a widow and a mother; she took care never again to present herself as a free and untrammelled woman. In the Samhain 1905 convention of Cumann na nGaedheal (by now Sinn Féin) she was not reelected as vice-president.

Centred in France

Maud Gonne's life became centred in France, as her separation and its terms were valid only there. Fear of a kidnap attempt by MacBride remained alive for some years. This, however, did not preclude occasional trips to Ireland. She presided at an Inghinidhe meeting where Helena Molony proposed to launch a new women's nationalist journal, Bean na hÉireann, in 1908. She was active in social causes, organising food for poor children and for the families of striking workers in the 1913 Dublin lock-out.

Yeats regularly visited Maud Gonne at her Colleville home in Normandy; they had a brief affair, which began on the astral plane in June 1908 and was consummated in December. She ended the affair in May 1909, but they remained close friends.

In 1910 she was involved in voluntary relief work during the Paris floods. In 1910 and 1911 she spent more time in Ireland on a campaign for the provision of meals to Dublin schoolchildren, which entailed cooperation with other social and national groupings.

Between then and the outbreak of war, she devoted her energies to researching free school meals elsewhere, and in 1914, with the assistance of Stephen Gwynn, succeeded in getting the free meals act extended to Ireland.

The outbreak of the first world war greatly distressed her. With her daughter Iseult she nursed in the Pyrenees and at Paris and Paris-Plage in French military hospitals during the war. The 1916 Easter rising and the execution of John MacBride transformed her life. She wore mourning and called herself Maud Gonne MacBride, a title she had abandoned after the breakdown of her marriage some twelve years before, stating that

‘Major MacBride by his death has left a name for Seagan to be proud of. Those who die for Ireland are sacred’.

Widowhood and republicanism

Yeats proposed to Maud Gonne in July 1916, and on being rejected proposed unsuccessfully to Iseult. Initially prevented from travelling to Ireland under the defence of the realm act, in December 1917 Maud Gonne returned secretly to Dublin.

In May 1918 she was arrested for alleged involvement in a pro-German conspiracy and transferred to Holloway prison in London, where she was interned along with Kathleen Clarke and Constance Markievicz.

After a lengthy campaign spearheaded by Yeats, Joseph King MP and 14-year-old Seán, she was released on grounds of ill health – her tuberculosis had returned – in November 1918 and returned to Dublin.

Her return to Dublin precipitated a terrible row with Yeats: she expected him to honour their earlier agreement that he would vacate the house as and when she needed it; he was unwilling to disturb his wife George, who was pregnant and dangerously ill with pneumonia. Although they eventually patched up their differences, their friendship never fully recovered.

In January 1919 her sister Kathleen died of tuberculosis in Switzerland, a further blow in what was for her the most turbulent of decades. In 1920 Iseult Gonne married the writer Francis Stuart, whom Maud Gonne thought vicious and unstable.

This marriage was troubled from the beginning, with violence and furious arguments on both sides. The couple briefly separated, to Maud's relief, but reunited after the birth of their daughter Dolores. When this child died of meningitis in July 1921, Maud supported Iseult through her grief, and took the family to the Continent to recuperate.

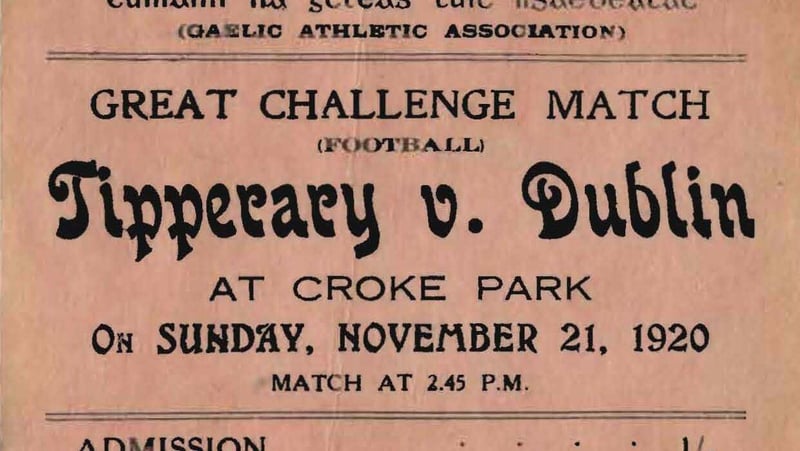

War of Independence

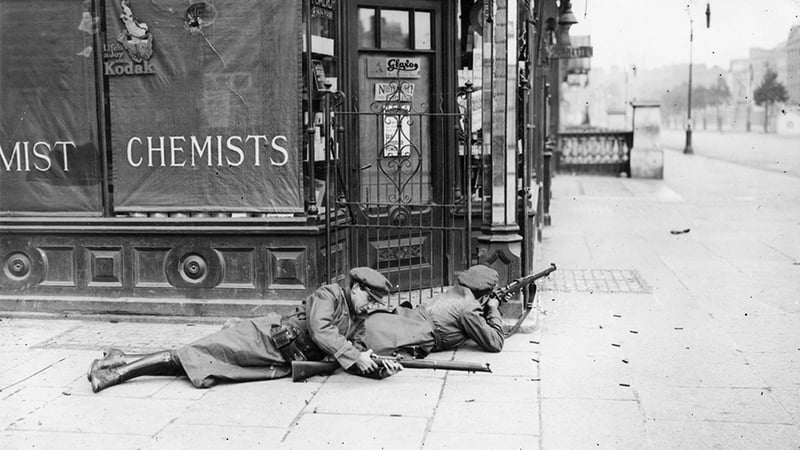

During the War of Independence, Maud resumed some of her political activities. She was generally to be found at the forefront of the crowds outside Irish prisons on execution days, and often supported the families of the condemned men.

She also became involved in the Irish White Cross, which was established to provide relief for distressed areas. In this she worked alongside Charlotte Despard, sister of Lord French, whom she had met in London in 1918.

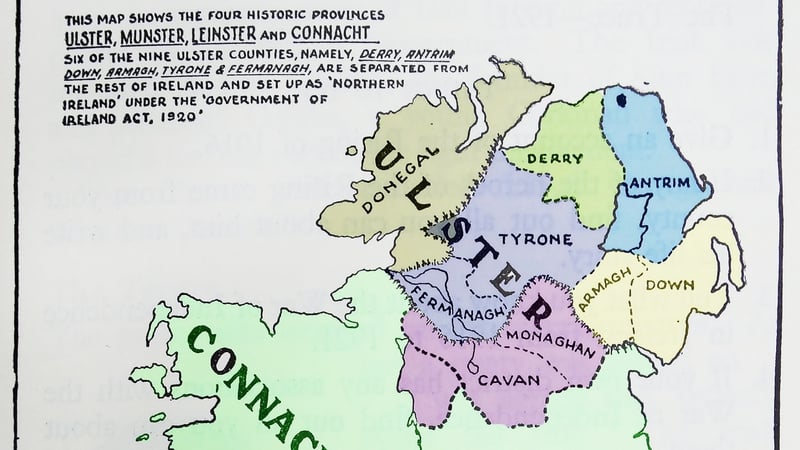

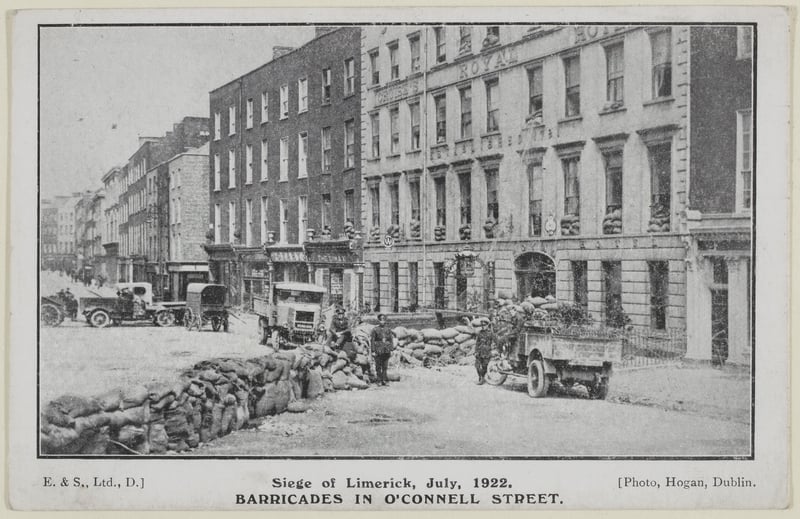

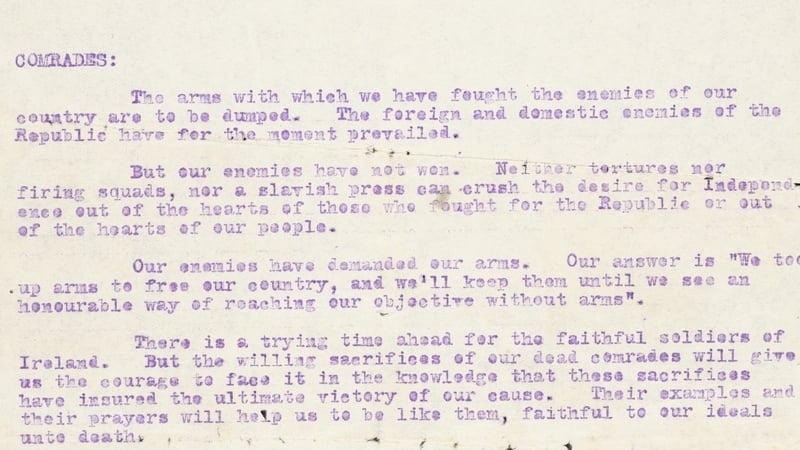

Maud initially accepted the treaty of 1921, partly because of her relationship with Griffith, a stance which for a brief time caused something of a rift with 17-year-old Seán, a member of the IRA. But after Griffith's death she bitterly attacked the Free State government and was twice imprisoned in 1923.

Other close friends, such as Dorothy Macardle and Constance Markievicz, also opposed the treaty. She frequently led public demonstrations against the Free State government, wrote for the radical republican press, and retained her long-standing concern for and engagement with the plight of political prisoners.

She was the driving force in the Women's Prisoners’ Defence League and liaised internationally on prison issues. She was a one-woman powerhouse for a range of political campaigns in the succeeding decades; these remain historically under-researched. Her energy was indefatigable.

She maintained close friendships in the network of republican women within which she operated, particularly with Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and Helena Molony. At Roebuck House, Clonskeagh, which she and Charlotte Despard purchased in 1922, she supplemented her political activities by operating a jam-factory and other cottage industries to provide employment for republicans in need. The house was the subject of frequent raids by the military and civil forces of the Free State.

De Valera's achievement of power in 1932 brought her no satisfaction. Her journal Prison Bars drew attention to the plight of republican prisoners. After the outbreak of war she redoubled her efforts on behalf of republican internees in the Curragh, especially involving herself in the plight of the hunger-strikers who died. Her son Seán MacBride legally represented many of these prisoners.

The Second World War and later years

In international politics Maud Gonne's views were idiosyncratic: in 1938 she pressed what she perceived to be the positive aspects of both fascism and communism as a model for Ireland. But by the outbreak of war in 1939 she was unabashedly pro-German, her reflexive anglophobia combining with her longstanding anti-Semitism, and wrote seeking propaganda material from the Deutsche Fichte Bund.

She was a close friend of Dr Eduard Hempel, the German minister in Dublin, and his wife Evelyn, whom she regularly entertained at Roebuck House.

She was under the surveillance of Irish military intelligence, who suspected her of involvement in the Hermann Goertz affair of 1940, an imbroglio implicating all the adult members of the Gonne–MacBride–Stuart clan. After the war, along with Goertz, Maud Gonne was a founder member of the Save the German Children campaign, which aimed to provide foster-homes for catholic German war orphans.

Maud lived at Roebuck House till her death, with her son, daughter-in-law Catalina (‘Kid’) Bulfin (1901–76), and much-loved grandchildren, Anna and Tiernan. In 1938 she published an autobiography, A Servant of the Queen, which ends with her marriage to John MacBride; a planned second volume of reminiscences never appeared.

She took pride in Seán MacBride's career, both as IRA chief-of-staff (1936) and cabinet minister (1948–51). She remained very close to her daughter, although never acknowledging the relationship. Maud Gonne died on 27 April 1953: her last recorded words were ‘I feel now an ineffable joy’. Georges Gonne's bootees were placed in the coffin at her request, and crowds followed the funeral procession to Glasnevin cemetery on 29 April.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography is Ireland's national biographical dictionary. Devised, researched, written and edited under the auspices of the Royal Irish Academy, its online edition covers nearly 11,000 lives. Read more about the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Forgotten: The Widows of the Irish Revolution aired on May 19th on RTE1 at 10.15pm and you can watch it here. This production was supported through the Decade of Centenaries Programme 2012-2023 by the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media.

The NGI holds a portrait of Maud Gonne in oils by Sarah Purser (c.1889), a pastel drawing by Purser (1898), a pencil and watercolour drawing by J. B. Yeats (1907), and a chalk and charcoal drawing by Seán O'Sullivan (1929). The Hugh Lane Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin, holds a plaster bust by Laurence Campbell and another oil by Sarah Purser. Photographs of Maud Gonne are in the NLI.

Sources

Maud Gonne MacBride, A servant of the queen (1938; new ed. 1994); Mme Gonne MacBride, Bureau of Military History, witness statement no 317 (no date), NAI, Dublin; NLI, Fred Allen papers MSS 29812–17, 29819–20, 29826; W. B. Yeats, Autobiographies (1955); W. B. Yeats, Memoirs, ed. D. Donoghue (1972); Samuel Levenson, Maud Gonne (1976); Nancy Cardoza, Maud Gonne: lucky eyes and a high heart (1979); Conrad Balliett, ‘The lives – and lies – of Maud Gonne’, Éire– Ireland, cxliv, no. 3 (fall 1979), 17–44; M. Ward, Maud Gonne: Ireland's Joan of Arc (1990); A. MacBride White and A. N. Jeffares (ed.), The Gonne–Yeats letters, 1893–1938 (1992); Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, Gender and history in Yeats's love poetry (1993); Frank Callanan, T. M. Healy (1996); R. F. Foster, W. B. Yeats: a life (2 vols, 1997, 2003); Senia Paseta, ‘Nationalist responses to two royal visits to Ireland, 1900 and 1903’, IHS, xxi (1998–9), 488–504; Karen Steele, ‘Maud Gonne and the United Irishman’, New Hibernia Review, iii, no. 2 (1999); Janette Condon, ‘The patriotic children's treat: Irish nationalism and children's culture at the twilight of empire’, Irish Studies Review, viii, no. 2 (2000), 167–78; Karen Steele, ‘Biography as promotional discourse: the case of Maud Gonne’, Cultural Studies: Theorising Politics, Politicizing Theory, xv, no. 1 (Jan. 2001), 138–60; Margaret O'Callaghan, ‘Women and politics in independent Ireland, 1921–68’, Field Day anthology of Irish writing, v (2002), 120–34; Richard J. Finneran (ed.), The Yeats reader: a portable compendium of poetry, drama, and prose (2002); Karen Steele (ed. and introduction), Maud Gonne's Irish nationalist writings 1895–1946 (2004); Caoimhghín S. Breathnach, ‘Maud Gonne MacBride (1866–1953): an indomitable consumptive’, Journal of Medical Biography, xiii (2005), 232–40; Lucy McDiarmid, The Irish art of controversy (2005); J. Kelly and R. Schuchard (ed.), The collected letters of W. B. Yeats, iv (2005); Andrea Bobotis, ‘Rival maternities; Maud Gonne, Queen Victoria and the reign of the political mother’, Victorian Studies, xlix, no. 1 (2006), 63–83; Karen Steele, ‘Voices for Erin: Maud Gonne, Inghinidhe na hÉireann and the United Irishman’, Women, press and politics during the Irish revival (2007), 66–105; Deirdre Toomey, article in ODNB

PUBLISHING INFORMATION

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3318/dib.005110.v1

Originally published October 2009 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography

Last revised October 2009