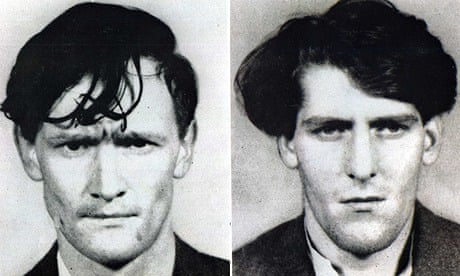

As they were led to the gallows there was little fuss. No public outcry, no headlines indicated that the executions of Gwynne Evans and Peter Allen would be remembered as anything other than run-of-the-mill.

The deaths of the two convicted murderers, hanged with little ceremony at separate prisons at 8am on 13 August 1964, made only a couple of lines in the national press.

Exactly 50 years later, however, the names Evans and Allen – two criminals who bludgeoned a man to death to steal £10 – are a significant footnote in the annals of abolitionist history.

As the last two people executed in Britain, the macabre anniversary of their deaths at Strangeways prison in Manchester and Walton prison in Liverpool is generating more publicity than their crime and punishment ever did at the time.

Evans, 24, and Allen, 21, were unlucky with their timing. Two months after they were executed Labour came to power, bringing a Commons vote to suspend capital punishment for five years in the 1965 Murder Act, a move made permanent in 1969.

At the time of their convictions, the 1957 Homicide Act had already removed the automatic death penalty for all murders, though exceptions included any murder committed for theft.

The criminologist Steve Fielding, author of more than 20 books on British hangings, believes the lack of publicity was due to the fact that, by sensationalist standards, the Evans and Allen murder was "quite low key".

The two jobless Preston men travelled to the Cumbria home of John "Jack" West, a 53-year-old laundry van driver known to Evans, in a stolen car with Allen's wife and two children, on 7 April 1964. The two planned to rob the bachelor, but then killed him.

A neighbour in the village of Seaton, awoken by a suspicious noise, saw the car disappearing down the street. West's semi-naked body was later found in a pool of blood.

Within 48 hours both men had been arrested and charged, police having been greatly aided by Evans leaving his raincoat at the scene. They were convicted in June, and had their appeals against the death sentences rejected on 21 July. A date for execution was set for 13 August.

At Walton prison, Robert "Jock" Stewart, was Allen's hangman. Fielding said: "He [Stewart] mentioned that on the day before the execution, when Allen was visited by his wife for the last time, they were separated by a piece of what was supposed to be bullet-proofed glass. And, as the interview came to a close, [Allen] hurled himself at it.

"He cracked the glass and broke his thumb. So, on the morning of the execution when Stewart went to pin his hands behind his back, he had a big bandage on where he broke his thumb.

"As he was led from the condemned cell to the gallows, he shouted 'Jesus.'"

Some 20 years ago, as part of his research, Fielding travelled to Liverpool to meet the assistant hangman, who has since died. "He said it was a run-of-the mill execution, just like all the others he had carried out. There was nothing sensational about it.

"Of course, they didn't know at the time it was going to be the last execution.

"It didn't get much publicity at the time. Certainly, two guys from Preston who had committed a murder up in Cumbria, it isn't going to get the London media buzzing, is it?"

Abolitionists believe the UK should be proud of the stand it took back then to abandon capital punishment.

"In reflecting on [these] 50 years I think what we would hope people would take from it is, first of all, a sense of pride that the UK is an abolitionist country and has been for such a long time," said Amnesty International's director of global issues, Audrey Gaughran.

Globally, there was a continuous downward trend in the number of executions, she said. Those calling for the reinstatement of capital punishment often saw it as "a quick fix, particularly around elections times", rather than addressing perceptions of crime.

"Among the things we have learned [in the last 50 years] is that convictions are not always safe," she said. That was one of the biggest arguments against it in the UK when it was abolished, "the issue of the irreversibility of the death penalty".

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion