Was He Framed for Killing Black Kids to Get the Klan off the Hook?

It is useful to know, if you are unfamiliar with the string of gruesome killings collectively known as the Atlanta Missing and Murdered Children’s cases, that no one was ever formally charged in the killings. The person or persons who, from 1979 to 1981, snatched at least two dozen kids from their families and communities, disposing of their young bodies in local rivers, woods, and long abandoned buildings, never faced charges for those killings even as authorities declared that the cases had been solved and the killer convicted of other crimes.

There are many homicides that police fail to solve, and unsurprisingly, the murders of Black people are statistically far less likely to be cleared than those of whites. So it is perhaps unsurprising that 40 years ago, police quickly closed the books on a case involving the killings of 29 young adults and children — all Black, mostly male, most of them 15 or younger, and many from Atlanta’s poorest neighborhoods — without an arrest, trial or conviction.

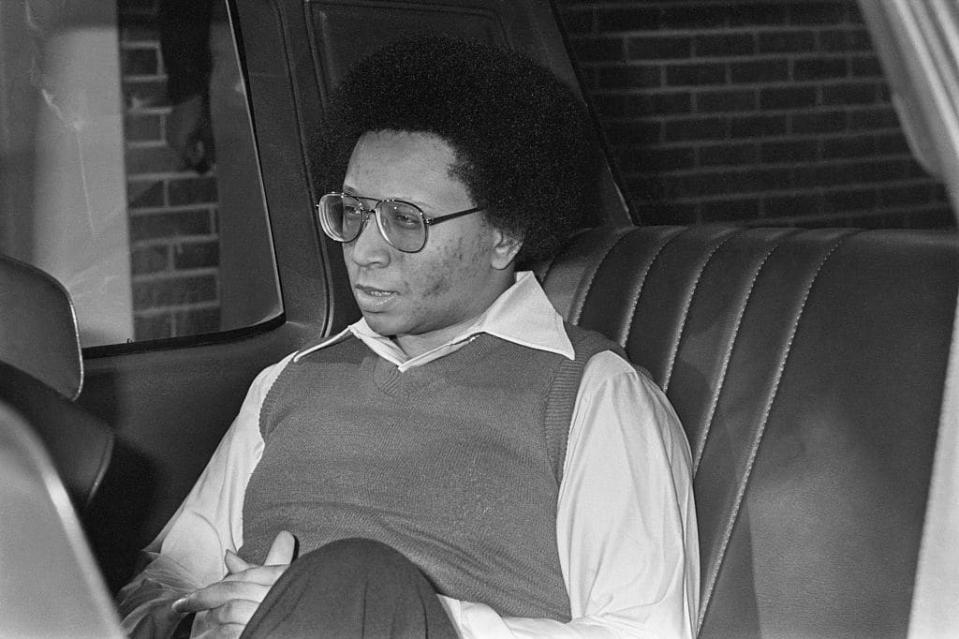

And yet, Wayne Williams has served nearly four decades of two life sentences in prison, partly because police, FBI investigators and prosecutors made him the only public suspect in the murders. Williams — a local Black 23-year-old who had aspirations as a talent scout and photographer — was arrested in 1981 for the murders of 27-year-old Nathaniel Cater and 21-year-old Jimmy Ray Payne. During Williams’ murder trial for those two young adults, prosecutors pulled an unorthodox legal segue, attributing 10 of the child murders to Williams, none of which he was facing charges for.

Pointing to Williams’ conviction for the killings of Payne and Cater as proof that he had also killed 23 children, police quickly shuttered the Missing and Murdered Children’s task force and the FBI folded its investigation.

Atlanta’s majority-Black political class — including the city’s first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, first Black police chief, George Napper, and City Council President Marvin Arrington — could return to claims that Atlanta, rising capital of the New South, was a national hub for black middle-class life. The killings had threatened to tarnish Atlanta’s image, burnished in the motto that it was a “City too Busy to Hate,” as a model of the post-civil rights South — a place where race relations were consistently improving and black folks were safe from white racism and terror. But it was impossible not to recognize the ways race and class impacted the city’s treatment of the crimes, from the initially slow response of law enforcement, which had historically overlapping membership with the Ku Klux Klan, to the media’s inattention to the cases until they could no longer be ignored. Williams’ arrest, for city officials, made all that revenue-threatening ugliness disappear.

“It has been resolved,” Arrington told the Atlanta Journal and Constitution in 1982. “Now we can get back to being the number one city in the world.”

Did the KKK or a Pedophile Ring Murder Dozens of Black Children in Atlanta?

The rest of the city remained skeptical though, including many of the parents whose children had been killed, who believed they hadn’t yet seen justice while their children’s murderer remained at large. Camille Bell, the mother of 9-year-old victim Yusuf Bell and one of the most vocal parent advocates, told a local news outlet at the time that Williams should be counted as “the 30th victim of the Atlanta slayings.”

But last Monday, outgoing Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms tweeted that a private Utah lab specializing in “old DNA evidence” will begin reexamining materials from the Missing and Murdered Children’s cases. The announcement came months after a July press conference when Bottoms said investigators had reexamined about some 40 percent of the copious evidence in their files, though she declined to identify the victims from whom DNA had been extracted in order to protect “integrity of the investigation.”

In the years since Williams was sent to prison, a staggering amount of evidence has emerged that suggests Atlanta officials were less interested in solving the murders of vulnerable black children than they were in ending a PR nightmare. I don’t want to re-litigate the case here, which several books, a podcast, and multiple documentaries have already done. But it’s worth noting that at hearings for a new trial in the early 1990s, Williams all-star legal team of William Kunstler, Ron Kuby, Bobby Lee Cook and Lynn Whatley revealed that police had never looked into a convicted sex offender who several eye witnesses identified as a suspect.

What’s more, multiple key prosecution witnesses have recanted, with one claiming police pressure to identify Williams and another admitting on Nightline that she had “never seen Wayne Williams before in my life” until trial day. A man who testified that he’d heard Williams making murderous anti-Black statements turned out to not only have faked his own identity on the stand but to have been a member of the Klan. In fact, the ‘90s hearings showed, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation had a secret investigation, dubbed “the 8100 file” that had been looking into possible Klan ties to the murders.

“It was more than just running down a leak. GBI convinced a judge they had probable cause to believe the Klan had information on, or had participated in the murders of one or more children. They got a wiretap warrant, which are not handed out like chicken fried steaks at the county fair,” Kuby told me, noting that Williams’ original defense team had been denied information about the existence of the 8100 file, and consequently, so was the Williams’ trial jury. “It was deliberately and consciously suppressed at the time because, we believe, of fear that anyone finding out about potential Klan involvement would escalate racial tensions in Atlanta and around the country to a point where it was dangerous. But you can't trade off people's liberty for a phony sense of racial peace. The entire file should be made public, and there should be serious consideration as to who made those decisions. And whether those types of decisions are still being made?”

The forensic evidence presented in Williams case — carpet fibers, dog fur, hair strands — have since been recognized as junk science. The same FBI lab that analyzed much of the material in Williams’ case was later found to be so poorly maintained that countless samples, in possibly thousands of cases, were likely compromised, and the federal agency admitted in 2015 that a majority of its microscopic hair analysts had “provided either testimony with erroneous statements or submitted laboratory reports with erroneous statements.” Researchers at the Innocence Project have written that “the misapplication of forensic science contributed to 52 percent of wrongful convictions” among those who the organization has freed from prison, many of who, like Williams, were imprisoned before the existence of DNA testing.

“This is why you find that a common phenomenon is newly elected district attorneys, in reviewing old cases, find lots of wrongful convictions. They were sending people to prison based on bite mark evidence in the ‘80s and ‘90s. That's like preventively detaining somebody because of the bumps on their skull. It’s exactly at the same level of nonsense,” says Kuby. “To the extent that physical evidence still exists, it certainly is worthwhile to have all of that retested under modern standards and see if any of the conclusions that were drawn by the so-called experts are supported and reinforced by the new evidence, or are discounted and disproved by the new science. That's just important in terms of Wayne Williams’ life, other people's understanding of the case, and basic principles of justice.”

There’s nothing to do now but wait, a feeling all too familiar to the parents who have spent more than 40 years searching for something that resembles fairness, and a man who may well have had four decades of his life stolen. For Atlantans both old enough to have lived through the era and those who came of age after the killings terrorized the town, the darkness of that era has never fully retreated. The city has long been hailed as an oasis of Black middle-class prosperity, but there is no lack of Black poverty — then or now — and poor Black Atlantans, in particular, have recognized the city’s refusal to fully deal with the horrors of that period.

The record can never be fully corrected, but perhaps this is a step towards amending it and toward a confession of how wrong so many powerful folks got things back then. Kuby has watched the process proceed with a kind of conservative optimism.

“After spending close to a decade trying to get the most minimal scrutiny from law enforcement, and utterly failing, I was very surprised the mayor decided it was time, that enough time had passed and people had passed, that it's now safe to look at what happened. Often it is true, you have to wait for a lot of people to retire, or shuffle off this mortal coil before it's safe to revisit these things when the institutional pressure no longer exists.”

“I was very happy to hear that all relevant agencies, as I understand it, said that they would fully cooperate. Am I skeptical as to what full cooperation means? I am. But more scrutiny of what happened is vitally important for the administration of justice,” Kuby added. “As somebody who in an earlier life was formally trained as both a cultural anthropologist and historian, I think it's very important that we understand this not-so-distant past, why things happened the way they happened. And most important, to make sure it does not happen again.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.