Flying at low altitude in a small airplane over the city of Puebla, south of Mexico City, Richard Stratton and his associates spotted their truck. They were smugglers. The truck was loaded with about 1.5 tons of cannabis, and it had disappeared off the street. So Stratton and his team took off in an airplane they owned to find it. “I had this guy named José watching the truck for me,” Stratton recalls. “I told him, ‘Whatever you do, do not leave this truck. Guard this truck.’ So the guy goes home for the Christmas holiday, and when he gets back to Puebla, the truck is gone.”

This story originally appeared in Volume 3 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

Now, from overhead, they spotted it. Which was great. Only problem? It was parked in the impound lot at a police station.

This was the late Seventies, the era of glittering disco balls and the so-called Hippie Mafia. The weed in the truck was hidden in a custom-built stash space, a false wall built into the front of the truck’s cargo area. It was then filled with furniture Stratton had purchased as a decoy, so the vehicle looked like any medium-sized moving truck being put to good use.

“The police knew something was fishy, but they didn’t know what,” Stratton recalls. “We paid them off, got out of there, and we were over the American border the next day.”

Stratton was, at the time, building his smuggling empire. He was also a writer with serious literary chops. He would have plenty of time to look back on his smuggling business, what went right and what went wrong. After he was busted in 1982 at the Sheraton Senator Hotel at LAX, Norman Mailer and Doris Kearns Goodwin testified on his behalf at his trial. Nevertheless, he spent eight years in federal penitentiaries.

“What people don’t understand about the smuggling business is how, in a sense, simple it really is,”

says Stratton, today a Manhattan-based documentary filmmaker and author of a trilogy memoir called Cannabis Americana: Remembrance of the War on Plants. “It’s all about taking product and moving it from Point A to Point B without being arrested. It is all about transportation.”

Early on in his business, Stratton invested in an auto body shop in Lowell, Massachusetts. “We had a friend who needed help with money to start his business. So we supported him to buy a building, and he set up a legitimate body shop. But he had a side hustle. He built secret stash spaces into cars and trucks for us.”

Stratton’s fleet started out with six vehicles, all with custom-built stashes. He often preferred Chevy Suburbans, but his favorite smuggling vehicle was a 1968 International Harvester Travelall station wagon that he had fully restored. “It was beautiful, and it looked like a family vehicle so no one would ever suspect it,” he recalls. “It had these big heavy doors. You could take the door panels off, load up the doors, then put the panels back on. You could put 50 to 60 kilos of hash in there.” It was just like the Lincoln in The French Connection, only this wasn’t Hollywood. Stratton used that International wagon to travel back and forth over the Canadian border.

When he started in the Seventies, smuggling cannabis was a small-stakes game, considered by many as a victimless crime. (Stratton never dealt in any heavy drugs like cocaine.) But as Reagan’s “War on Drugs” arrived and his business grew, the stakes went through the roof. The game became all about how to imagine vehicles and how to customize vehicles to stay one step ahead of the law.

The next time you are driving on a highway, take a look around at all those Toyota Priuses and Audi A4s carrying commuters and soccer moms. “About two or three of every 50 vehicles you see on the highway are likely to be carrying illegal contraband,” says a retired Drug Enforcement Agency operative who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “There is no way to stop and search every car. On a good year, law enforcement will bust about 15 percent of what’s coming into this country. And what people don’t realize is that smugglers will always take the path of least resistance. Which means they are likely to be on the same highways as you are. I-80 across the country, I-5 up and down the West Coast, I-95 on the East Coast. The way the bigger operations see it is, if they lose a load, so what? To them that’s like paying taxes.”

The story goes back as far as the automobile itself. Since the early days, cars have been used by the underworld and the law in a constant battle of wits and weapons. During Prohibition in the Twenties and after, moonshiners hopped up their Fords and Chevys and perfected dirt-road drifting techniques, hustling away from whistling sirens, carrying illegal loads of liquor. Al Capone’s custom-built bulletproof 1928 Cadillac Town Sedan became, for car nerds at least, as legendary as Capone himself. (It was up for sale for $1 million, as recently as last year.) John Dillinger—the original “Public Enemy Number One”—reportedly wrote a letter to Henry Ford thanking him for building such a speedy car.

Through the generations, however, no criminal industry has invested as much creativity in vehicle customization as smuggling. To put this story together, we interviewed three former smugglers who have collectively spent 40 years in prison, all of whom now lead law-abiding, family-man lives.

Arguably the most common vehicle customization technique is the truck with the false wall. One of the biggest weed smugglers of the Eighties—who was also an IMSA champion back when the series was jokingly called the International Marijuana Smuggling Association—remembers how effective the false wall was for his operation.

“We used tractor-trailers,” he says. “Take a 48-foot semi, and you could create a stash space of several feet up front. Then block that off with a wall. We used to fill up the [trailer] after that with brand-new hot tubs, so if we got pulled over, and the cops opened up the back of the truck, all they would see would be a load of hot tubs straight up to the ceiling. They would not be able to even get to the third wall without a significant investment of time and heavy moving equipment.” This smuggler also used vans loaded with two-by-fours. The boards at the top were standard length, ready for a cop to inspect. But at the bottom of the pile, weighted down by the ones on top, the boards were just 6 inches long, creating a stash space in the center of the vehicle.

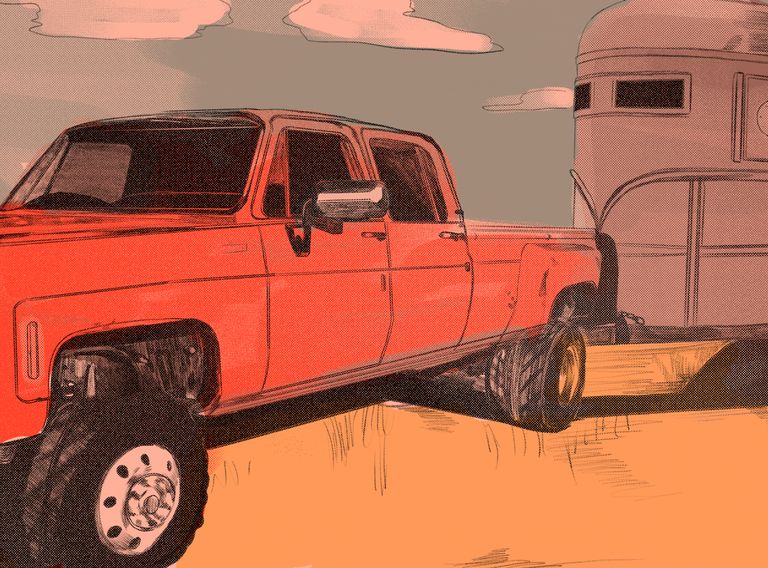

None of that, however, can compete with the cleverness of Richard Stratton’s most successful smuggling vehicle. “I always loved GMC dualie trucks,” he says, “pickups with two sets of dual wheels in back and a crew cab.” Using a 1978 GMC as a hauler, Stratton bought a horse trailer and built a fake floor into it, creating a large stash space. He would load the stash space with product and/or money, and put real live horses on top of it.

“The stash space had to be waterproof,” he says, “because the horses would be pissing all over the floor.” Meanwhile, the stink of manure helped cover the smell of cannabis. “No officer was going to pull us over, pull the horses out of the trailer, and search the thing. And even if they did, they wouldn’t find anything. We lugged horses routinely over the Mexican border [and all the way] to New York City, which was then, and still is today, the biggest cannabis market in the world.”

These days, technology has changed the way smugglers do their business and how the law combats their efforts. However, the most effective weapon the law has on its side has no lasers, nor computer chips. It has four legs and drools a lot. “If the cops had drug dogs when I was in business, I would have been screwed,” says “Bob,” a former Nevada drug smuggler who now lives in Chicago.

He specialized in building off-road smuggling vehicles modeled after the “pre-runner” trucks used by Baja 1000 competitors to scout the course before the race. “The first thing you needed to go into business was a good auto shop,” he recalls. “You needed to have grinders and plasma cutters and welders and the ability to fabricate out of raw steel. At the time, everyone in town knew me for building pre-runners as a hobby. So there was nothing weird about what I was doing. And there was a lot of off-road racing at the time in Nevada, which meant, for me, a steady flow of all the custom parts I needed.”

His most “badass” truck, Bob says, was based off of a 1985 Ford F-150 he built in 1998. “The first thing I did was take the whole thing apart, then rebuild it with long-travel suspension. I built a full 4130 chromoly cage and had all my tools on board so if I got stuck or broke down in the desert, I could fix the truck.” It had stash spaces all over it, including an extra gas tank and jerricans for fuel, all of which had stashes in them. “The stashes were waterproof,” he recalls, “so if the police picked up a jerrican, the can could actually pour out real fuel and the cop would never know there was a stash in the bottom of it.”

Why off-road vehicles? Bob lived in the middle of one of the biggest deserts in the world. Everything he held—product or money—he kept buried in holes deep in terrainless desert, only found by GPS coordinates (this was when GPS first became available to consumers). And, if he ever found himself in a police chase (which never happened), he could make a turn and head off into endless stretches of nothing, something no cop car could do. “Out in the desert,” he says, “that F-150 could outrun a helicopter.”

It all worked beautifully—until it didn’t. Bob did 6 ½ years in prison. Now a father of three, he still builds off-road trucks for fun. He admits that he still has buckets of money buried in Nevada, too. But he never wants to set foot in that state again.

In the never-ending quest to find the perfect customized smuggling mobile, Richard Stratton remembers his all-time favorite.

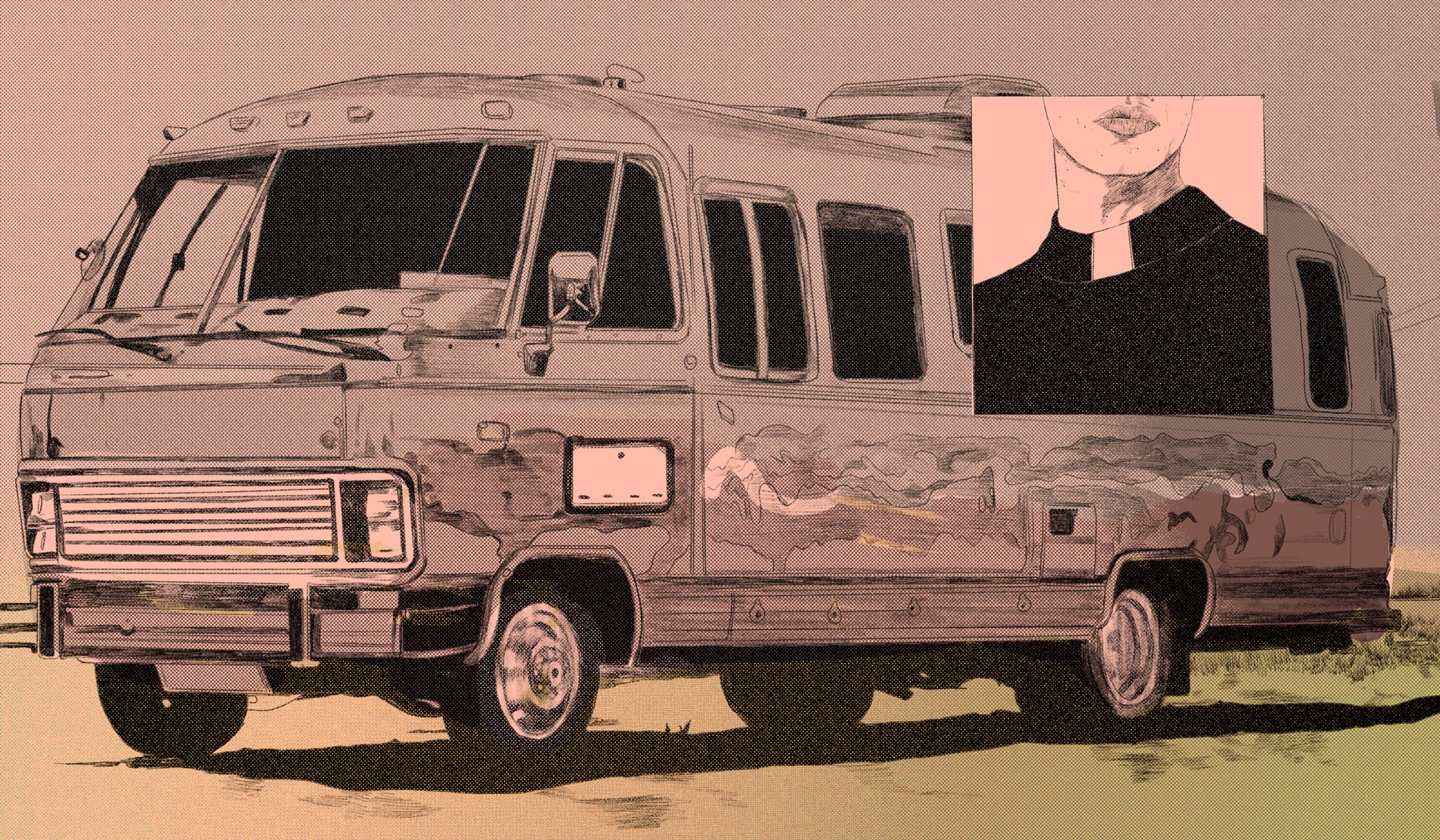

“We were doing a lot of business at the Mexican border,” he recalls. This was the early Eighties. Business was good. “I was insane, buying boats and airplanes and 18-wheelers. We were looking for motorhomes at the time that we could use to transport product up to New York. One day, one of my guys found a motorhome for sale, one of those beautiful silver Airstreams. It had room for four to sleep comfortably and a full kitchen. Only this one had been previously used by a company called Global Evangelism Television, as a traveling bible-belt TV production studio. It had a picture of a Bible and a television camera on the side and the company logo, which read in huge letters, global evangelism television.”

The guy who found the motorhome told Stratton, “It’s in good shape, but we have to have it painted.”

“No way!” said Stratton. “Leave it just like it is. It’s perfect.”

The rig cost about $20,000. Profit from a single trip to New York paid off that bill. “The guy who was driving it for me had this long beard,” Stratton recalls. “He looked like a priest. His name was Foley, and we called him Father Foley. I practically lived on that thing for months.” Stratton and his crew traveled back and forth from Texas to New York in their “Global Evangelism Television Machine” some 30 times, right up until the time that he was busted in 1982. By that time, the War on Drugs was becoming just that—a war. It turned out to be a good time to get out of the business anyway.

Today, the era of the Hippie Mafia has given way to a new one of murderous cartels, innocent victims, and horrifying carnage. But in a sense, the smuggling strategy remains the same. It is still about creating imaginative vehicles to transport product from point A to point B without getting arrested. The smugglers’ vehicle of choice has become the “clone car,” painted to look like an ordinary commercial or government vehicle. Not long ago, police in Texas busted a fake U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service truck packing $1.6 million worth of cannabis, and a cloned Texas Department of Transportation truck carrying nearly a ton of marijuana. They even busted the driver of an 18-wheeler painted to look exactly like a U.S. Postal Service delivery truck. Law enforcement expects, in the future, to see the use of self-driving cars with no human element at all.

At the extreme, there are the Narco submariners, who got publicity recently after a vessel was busted with 12,000 pounds of cocaine last year. For every submarine that gets caught, how many make it through that we never hear about? “A cartel might put up a job listing on the dark web for a nautical engineer for $300,000 a year, for someone who can build submarines,” says the DEA man. “The cartels today have unlimited resources. There is nothing they won’t do. And no one they won’t do it to.”

1968 International Harvester

“I loved it because it looked like a car some old geezer would be driving,” says former smuggler Richard Stratton of his International Harvester. The Travelall, built from 1953 to 1975 to compete with Chevy’s Suburban, was a harbinger of the SUV wave to come, a truck ahead of its time. Stratton’s had some special features.

•Heavy-duty shock absorbers made sure that the truck didn’t sag when loaded up with hundreds of pounds of cannabis and money.

•Custom-built stash spaces in all four doors could hold many bricks of pressed Mexican marijuana.

•Two more stash spaces were custom-built under the back seat.

•A powerful stereo was key for long-distance drives. On heavy rotation: Bob Marley, Neil Young.

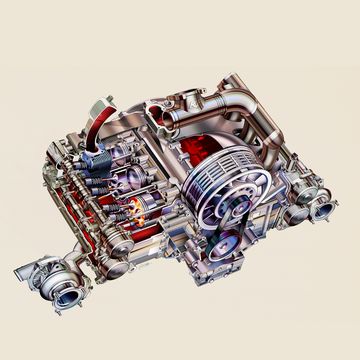

•Top of the line 345-cubic inch V-8. Reliability was imperative: A broken-down car attracts police attention.

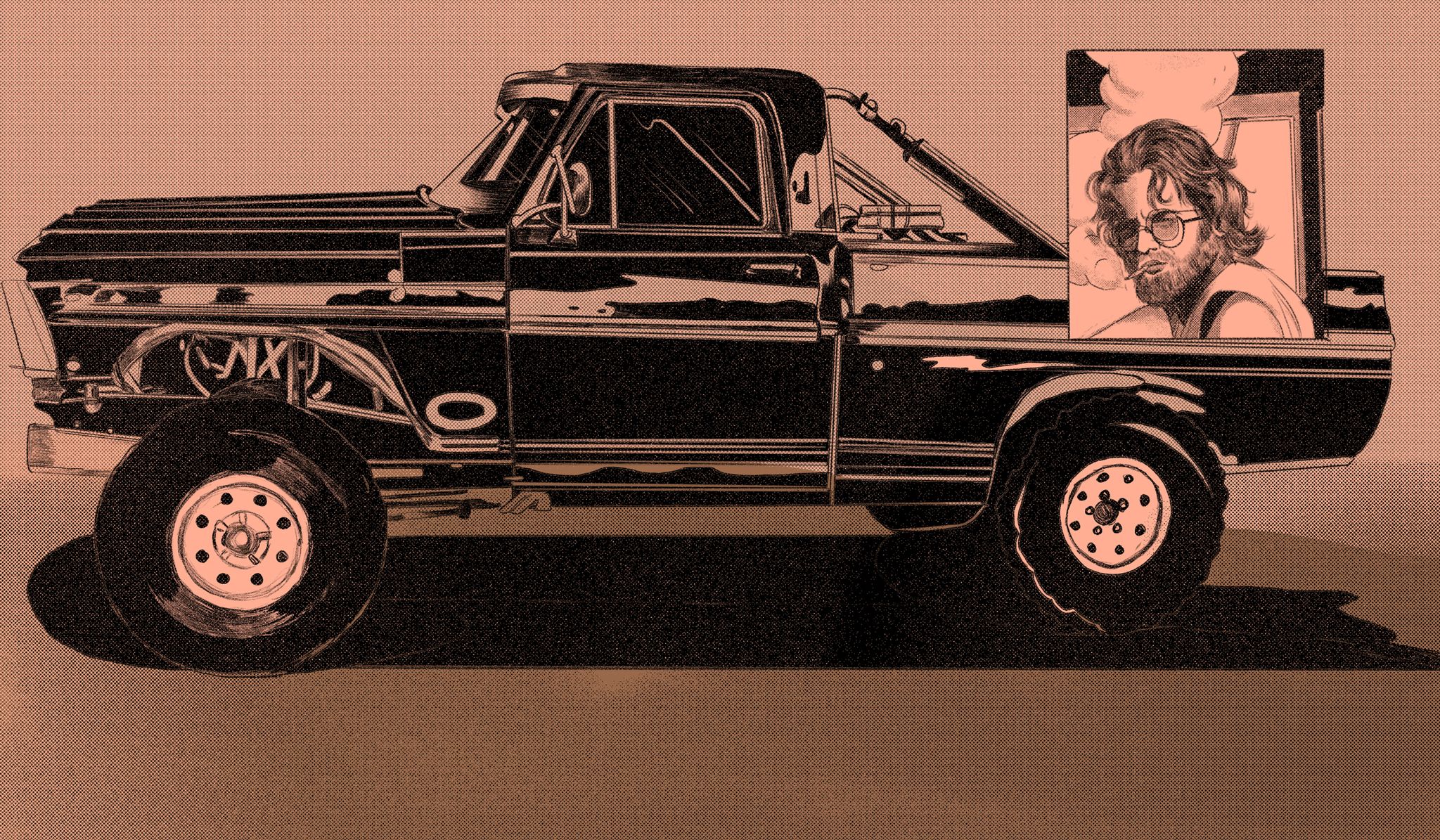

1985 Ford F150:

Off-road racers created a whole new category of custom vehicles: Pre-runners, modified street trucks built to scout a desert race course ahead of the event. Retired smuggler “Bob” built his pre-runners with extra features to carry product and money deep into the desert where no cop car could ever follow.

•Full roll cage built into the interior, mounted on the F-150’s frame.

•Prerunners often have extra gas tanks. This one’s carried more than gasoline.

•Jerricans had waterproof stash spaces built in. If a cop picked one up, he could pour fuel out and have no idea what else might be inside.

•Four shoebox-sized stash spaces were welded into the frame, two on each side of the transmission tunnel.

•Experienced off-road race driver at the wheel, ready for just about anything.

1979 Airstream Global Evangelism Machine:

Airstream started making travel trailers in the Thirties, but in the Seventies, the company launched its own line of motorhomes featuring the same Americana flavor. Ex-smuggler Richard Stratton found the perfect smuggling RV in Texas: a former mobile production studio for Global Evangelism Television.

•Four slept comfortably; so a crew could live on the road and continue working indefinitely.

•A full kitchen kept everyone fed and beers cold.

•Stratton had four custom built stash spaces tucked into the bottom of the vehicle.

•The smugglers left the signage from the previous owners on the motorhome—a perfect decoy.

This story originally appeared in Volume 3 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES