NPR’s Ari Shapiro reports on lessons learned behind the microphone – and in print

New memoir gives the inside scoop behind the familiar voice from ‘All Things Considered’ news program, the people he’s met during his career and his passion for performing

Ari Shapiro behind the microphone as host of NPR's 'All Things Considered.' (Stephen Voss/NPR)

Ari Shapiro behind the microphone as host of NPR's 'All Things Considered.' (Stephen Voss/NPR) Ari Shapiro (center) on a reporting trip to Colombia. (Ryan Kellman/NPR)

Ari Shapiro (center) on a reporting trip to Colombia. (Ryan Kellman/NPR) Ari Shapiro (third from right) on a reporting trip to Zimbabwe, 2018. (Claire Harbage/NPR)

Ari Shapiro (third from right) on a reporting trip to Zimbabwe, 2018. (Claire Harbage/NPR) Ari Shapiro (right) with Alan Cumming performing in their Och & Oy! show. (Emilio Madrid)

Ari Shapiro (right) with Alan Cumming performing in their Och & Oy! show. (Emilio Madrid)

National Public Radio listeners may not know what Ari Shapiro looks like, but they will recognize his voice. Since 2015 he has been one of the hosts of the media organization’s flagship program All Things Considered. Before that, he was NPR’s Justice Department correspondent, White House correspondent and an international correspondent based in London.

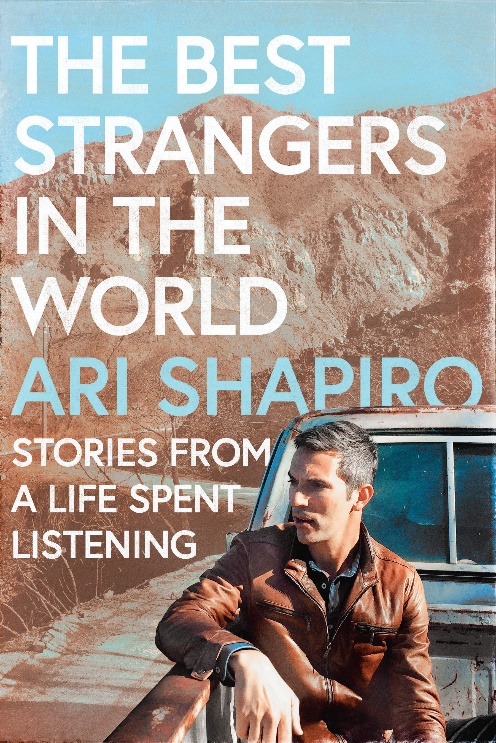

For two decades, Shapiro has pointed the microphone at others. Now he is telling his own narrative in a new memoir titled, “The Best Strangers in the World: Stories from a Life Spent Listening.” It will hit bookstore shelves on March 21.

The book is both a journey into episodes from Shapiro’s life and a meditation on journalism. He weaves the two threads into a colorful and insightful read balancing seriousness with fun.

In an interview with The Times of Israel from his home in Washington, DC, Shapiro, 44, said that upon reflection, he realized that as a translator of ideas and experiences from one group to another from a young age, he may well have been destined to become a journalist.

“When I was a little kid in Fargo, North Dakota, my brother and I were the only Jewish kids in our elementary school. And so from the first grade, I was going from classroom to classroom every December with a menorah and a dreidel explaining what Hanukkah was. And then I was the only out gay teenager at my high school in Portland, Oregon. And so once again, I was trying to be a translator for people to help them understand something unfamiliar,” Shapiro said.

“Eventually, I applied those skills to a career in journalism, where my big discovery was I could use those translation abilities to introduce audiences to people that I had no personal connection to beyond my journalistic interest,” he said.

Shapiro is also a guest singer with the cross-genre, multi-language Pink Martini band. He jumped head first into that gig with an initial performance in front of nearly 18,000 people at the Hollywood Bowl in 2009. Shapiro also performs with award-winning Scottish actor Alan Cumming in an original cabaret called Och & Oy!

Shapiro, who has been married to his husband Mike Gottlieb for nearly two decades, has little experience in print journalism. He always swore he would never write a book, but he decided it was worth giving it a shot. He hopes it will convey how he keeps his sunny demeanor.

“Fans often ask how I stay optimistic in the face of everything that’s happening in the world, particularly as I’m often chronicling some of the worst things going on. The people who you’ll meet in these pages are the people who remind me of all the good in the world, of all of the individuals who are working to make the world a better place, even in the face of adversity,” he said.

The following conversation with Shapiro was edited for brevity and clarity.

Almost every journalist will tell you that they are motivated by curiosity. What is your brand of this characteristic?

Even though I have had experience doing deep dive reporting — five years covering the Justice Department and four years covering the White House — what I love about my job hosting All Things Considered is that on a given day, I know that I’m going to learn about something new. That could be something in the field of science, politics, business, arts, or sports —literally anything.

I have colleagues who live for politics reporting or for national security reporting. That’s not me. I want to know what motivates people. I want to know about people’s experiences. And perhaps most importantly, I want to know how people who may seem very different from us actually have much more in common with all of us.

Why is public radio such a good fit for you? And why do you prefer radio over TV or print?

Let’s start with the public radio answer. I love that we are answerable only to our audience and that at the editorial meeting every day, the only consideration we have is how can we create the best show for our listeners that afternoon. We’re guided by our curiosity. We can be as wide-ranging as the human experience. And so editorially, that’s a really good fit for me.

And in terms of why radio, I think there’s something incredibly intimate about the sound of the human voice speaking to you. I grew up in a family that listened to public radio and so I know firsthand what it’s like to feel connected to a person who you’ve never met. And I don’t just mean the hosts. I mean the people who are sharing their stories. There’s something about bypassing the eyes and going straight from the ears to the brain that I think allows us to access our humanity, emotions, and imagination a little bit more easily than when everything is being provided to us in pictures on the television screen.

There’s something about bypassing the eyes and going straight from the ears to the brain

In the book, you deal with the tension between objectivity and subjectivity when it comes to reporting. Can you elaborate on that?

I think objectivity is important and a worthy goal. At the same time, I think we all bring our whole selves to any story that we tell. And those two things can exist in tension with each other, and that is part of what I wanted to explore in this book.

I do not see myself as a partisan or an advocate. I aspire to give every story I tell and every person I interview a fair shake, and give an accurate reflection of their point of view and where they come from because the stories that I tell — apart from this memoir — are not about me. At the same time, the history and identity that I carry and the person I am inform the stories I tell in certain contexts more than others. And so that push-pull was something that I wanted to explore throughout this book.

Can you give an example of this?

One example that I write about in the book is the [2016 Orlando, Florida] Pulse nightclub shooting. When I was covering that massacre in a gay bar, I knew that I had been to gay bars and those were places that held personal meaning for me. I knew that I had been out to gay bars in Orlando, and made friends with bartenders years earlier. What I didn’t know until the end of that reporting process was that the bar where I had made friends with the bartenders was Pulse nightclub. If you look back at my reporting of that massacre, I think the stories I told were stronger because of the experience that I brought to the project of covering the story. That was actually an asset rather than an obstacle.

Similarly, when I see my colleagues who are people of color reporting on fights over racial justice, or when I see my colleagues who can get pregnant cover fights over reproductive rights, I think their lived experience adds value rather than detracts from their authority.

So you are differentiating between bringing your lived experience, knowledge, and background to a story and putting yourself into it.

Absolutely. I’m not advocating for putting yourself into the story per se.

I think in the vast majority of instances, the person I am and the identity I bring to a reporting project are irrelevant. I’m not the central character in the story. Even when I look at my coverage of the Pulse nightclub shooting, which was very much tied to my own life and history, I was not the main character in any of those stories. What I was able to do was listen more empathetically and ask questions that were perhaps more nuanced and insightful because of the experience that I had.

Was writing a memoir challenging for you?

After 20 years as a journalist, it was deeply ingrained in me that if my storytelling is about me, I’m doing it wrong. I’m always pointing the microphone at someone else. And so this experience of turning it back on myself, and putting myself at the center of the story in this book was a learning curve and was not easy for me to dive into.

After 20 years as a journalist it was deeply ingrained in me that if my storytelling is about me, I’m doing it wrong

Did you feel exposed?

I felt self-indulgent. I felt like I was a vegetarian who sneaks off into the corner to eat a cheeseburger. It felt like I was betraying the guidelines and ethics of my chosen profession.

In the book, you quote what you believe is a German saying about having one leg to stand on and one to dance on. You were referring to your main gig as a journalist and your side one as a singer and performer.

I didn’t succeed in fact-checking that saying, but it’s great if it’s real.

Let’s pretend it is. Or say it’s a Yiddish saying.

It actually does sound very Yiddish.

So why is it important for you to perform with Pink Martini and Alan Cumming?

On a surface level, singing with Pink Martini and touring with Alan Cumming are two of the most fun things I’ve ever done in my life. And I think making room for fun in our lives is crucially important. But to go a level deeper, I thought for many years that the performance side of my life was the opposite side of the coin from the journalism side; that these were two sorts of fractured personalities. Partly through writing this book, I realized that they actually do have a lot in common: The act of listening, connecting with an audience, and helping people relate to one another. There’s a common thread that runs through all of these activities. And so at this point, I no longer feel like these are different personalities. I feel like there are different ways of doing the same thing.

You joked that at the start of your career, you knew you had arrived as a journalist when you got your first hate mail. But on a serious note, have you been targeted as antisemitism has increased in recent years?

I have noticed Twitter is becoming a more hostile place. I don’t know if that is because of Elon Musk or the trend in antisemitism. I have appeared on lists of Jews in the media, but I am thankful that I have not personally experienced the intense, virulent attacks that some of my colleagues have. I am not exactly sure why. But I am aware that this tide is rising and I see it all around, but at least so far I have not personally felt severely targeted by that.

“The Best Strangers in the World: Stories from a Life Spent Listening” by Ari Shapiro

This article contains affiliate links. If you use these links to buy something, The Times of Israel may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

Are you relying on The Times of Israel for accurate and timely coverage right now? If so, please join The Times of Israel Community. For as little as $6/month, you will:

- Support our independent journalists who are working around the clock;

- Read ToI with a clear, ads-free experience on our site, apps and emails; and

- Gain access to exclusive content shared only with the ToI Community, including exclusive webinars with our reporters and weekly letters from founding editor David Horovitz.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel