Wherever you live, whatever language you speak, and however you fill your day — that day will be the same as everyone else’s, in one significant way. The sun will rise in the morning and set in the evening. The sun tends to be quite predictable and follows a regular anticipated cycle. We can set our watches by the sun — but a millennia ago, the sun bore a child — the calendar. Here are some interesting facts about the history of the Calendar.

The Nature of the Sun Brought with it Enough Calendar History to Produce a Calendar.

Very few things in this world can be depended on — but the sun is loyal, steady, and true. Its cycle is trustworthy year after year — making its emulation by all people through ages understandable.

At the same time each month, the shape of the moon will change. It will start as a crescent that fills the night sky, then shrinks; a process that takes about thirty sunsets and sunrises. The stars, too, will move across the sky, returning to their original positions after about 365 of those sunrises and sunsets.

Humans have noticed the night patterns for as long as they’ve had backs straight enough to stand and look to the sky. And they’ve tried to predict and measure those movements too, and for good reason. By counting days and the passage of the moon, they could predict changes in the weather.

These ancient people could tell when winter was approaching by when the days would grow longer or shorter. They would know when to plant crops; when to look for particular animals; when their own animals were likely to give birth, and when to give thanks to the gods.

Today, our history tells us to count those days to plan meetings, book vacations, plan events and a host of other things on our Calendars.

Our history depends entirely on the use of a calendar to organize our days, now, in our time. In this guide, we’re going to look at how the calendar has developed and how we use it today.

Calendars in Ancient Times

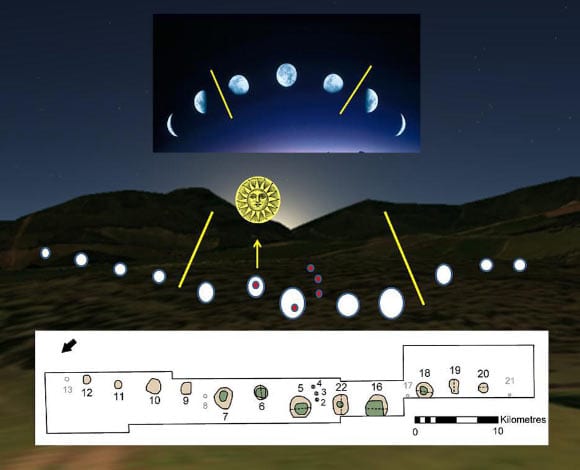

In 2013, British archeologists announced the discovery of what they claim as the world’s oldest calendar. The site at Warren Field in Scotland consists of twelve pits aligned with the southeast horizon. They pointed towards a hill associated with the sunrise on the midwinter solstice. Archeologists believe that hunter-gatherers used the pits to check the height and stage of the moon in order to track time in relation to the sun and the changing seasons.

The calendar in Scotland is about 10,000 years old, which makes the Warren Field in Scotland about twice as old as Stonehenge (discovered in 1978). People are more familiar with Stonehenge sight, an ancient stone circle in the south of England, which also aligns with the solstices.

The challenge with interpreting these sights, though, is that Neolithic people created and built the sights at a time when there were no written records. Archeologists have looked at the shape and alignment of the stones and the contents of nearby burial sights to figure out what other practices were conducted here, and what other secrets the sights may hold.

Stonehenge is more likely to have been a location for performing rituals at specific moments of the year than a way to keep track of time — although the structure is capable of being a calendar, also revealing times of the equinoxes and solstices — (which are not precisely the same thing). Recent findings show the Stonehenge sight was believed to hold curative, healing powers. Hunters might have used the Warren Field (Scotland) not only to give them “times of the year to plant or harvest,” but possibly to tell hunters when they could expect to start looking for particular kinds of migrating animals.

Evidence for some abilities needed to wait for the start of civilization and the first written calendars.

While early man might have used both sights used to mark time, some people say it’s unlikely that they used them to keep track of time permanently. The sights show that Neolithic peoples had a concrete concept of time passing and knew that cycles were predictable over time. Some sights indicate an ability to measure the passing of weeks or months.

The History of the Babylonian Calendar

The first cities were formed between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that originated in the Taurus mountains of southeastern Turkey. The headwaters diverge and run south through Syria and Iraq, and several tributaries are added from Iran before flowing into the Persian Gulf.

Ur, which was founded around 3,800 BC, would once have been a coastal city. Changes to the landscape now place it more than 200 kilometers from the sea; but at one point the Ur III empire would have stretched up through much of modern Iraq, incorporating a number of smaller cities.

Clay tablets marked by cuneiform writing indicate that before Ur incorporated them, those cities would have had their own calendars with their own names for the months of the year. Nippur, for example, had months called “du6-ku33,” or “Shiny Mound,” and “kin-dinanna,” or “Work of Inanna.”

The city of Umma had months that translate as “Harvest,” “Barley is at the quay” and “Firstfruit (offerings).” Each of the cities had a month called, “Extra,” that allowed them to reset the calendar in the same way as a leap year.

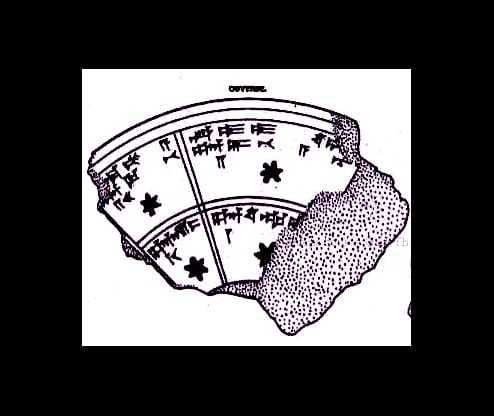

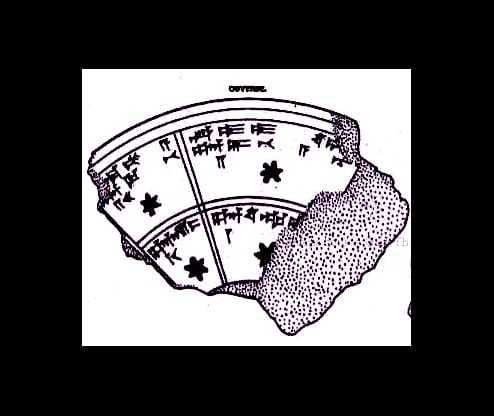

Drawing by Theophilus Pinches (1856 -1934) of Sm. 162 (from CT 33 11) in the British Museum

Image: Calendar fragment from the library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh ( you may wish to view this calendar on a site by the same name).

The conquests of King Shulgi, who ruled in the 21st century BC, united those calendars into the Umma calendar — and that calendar formed the basis of the Babylonian calendar. The Umma calendar, too, had twelve months and a thirteenth month every four years.

The calendar starts in the spring, around March or April in the Gregorian calendar, with Araḫ Nisānu, the “Month of the Sanctuary.” That’s followed by the “Month of the Bull,” which corresponds with the zodiac sign Taurus. The seventh month is the “Month of the Beginning,” and it begins the second half of the year — and is followed by the “Month of Laying Foundations.”

Babylonian weeks would not have been unfamiliar. Each seventh day was a rest day on which officials were prohibited from engaging in certain activities. For the Babylonian calendar — these same activities couldn’t be done on the 28th day of each month, either. On each rest day, Babylonians made offerings to a different god. Perhaps the strangest aspect of a Babylonian month would have been the length of the last week. Each week lasted seven days, but during the lunar cycle, the month, lasting 29 or 30 days, made it so the last week of each month lasted eight or nine days.

The History of the Egyptian Calendar

The Babylonian Empire lasted from around 1896 BC to 539 BC, reaching its peak during the reign of King Hammurabi (1792 BC to 1750 BC). At the same time that Babylonians were looking forward to the lengthy last weekend of the month, the Egyptian empire was growing in the west.

Scholars dispute the existence of early Egyptian calendars based on the rise of Sirius or the presence of a year lasting 360 days. But it’s clear that as early as 3,000 BC, Egyptians were interested in the yearly cycle. What interested them most was the annual flooding of the Nile. Each year between May and August according to the Gregorian calendar, the monsoon brings heavy rains to the Ethiopian highlands south of Egypt. The waters flow into the Nile, causing the river to flood its banks.

That flooding determined the size of the harvest. A system of dams and dikes drove the floodwater into fields to saturate the soil. The water that collected in the fields had to be sufficient to grow the crops through the dry season. A low flood meant a poor harvest.

But the floods also determined the pattern of the year. Egyptians divided their calendar into three seasons. The Flood Season lasted from around June to September and was when the Nile flooded and the waters inundated the fields. “Emergence” lasted from around October to January. Finally, the Low Water or harvest season took place between February and May. During the early dynasties of Egyptian history, the months within those seasons had numbers —“First Month of the Flood,” “Second Month of The Flood,” and so on. By the Middle Kingdom, however, the months had picked up names which have largely survived through the New Kingdom and Greek calendars to the current Coptic calendar.

The Calendar According to the Nile

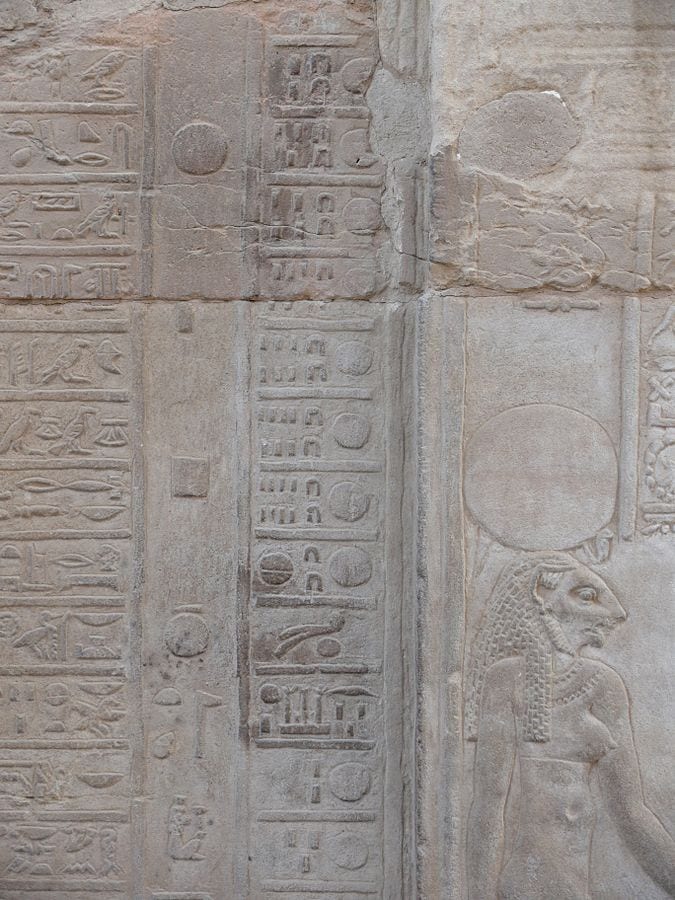

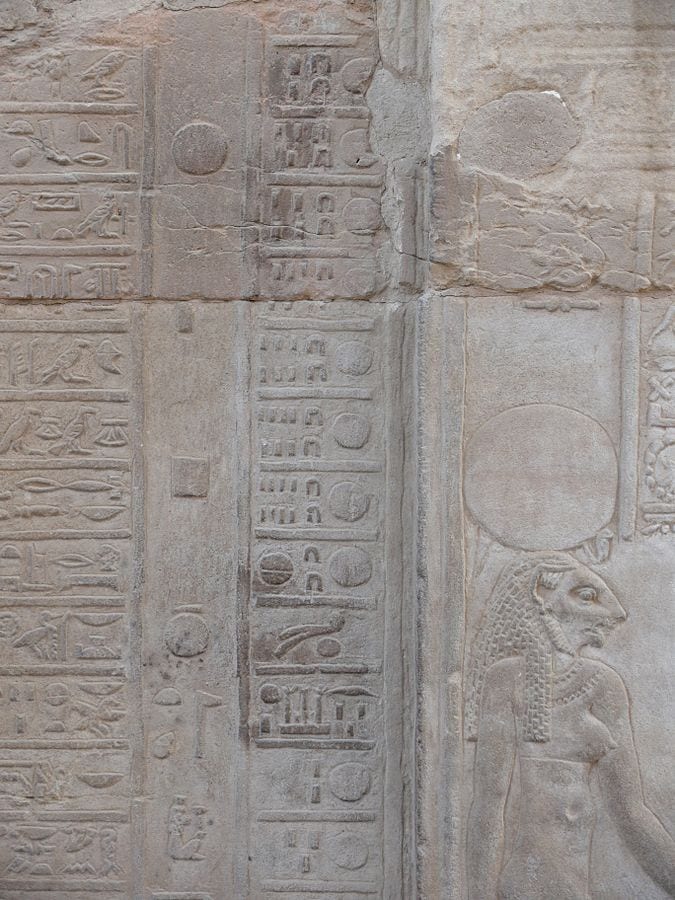

Image by Ad Meskens: Calendar in the temple of Kom Ombo showing the hieroglyphics for the days of the fourth month of the harvest and the first day of the first month of the flood.

The three periods determined by the rise and fall of the Nile formed the year, and they occurred regularly. They were as crucial as migrating birds were to the hunter-gatherers of the Scottish Isles — yet, no more predictable. While the rise and fall of the sun and the moon or the turning of the stars follow a definite pattern, the coming of the monsoon, like the flight of storks, depends on weather systems that vary from year to year.

While the seasonal calendar allowed Egyptian farmers to predict when they should open their dams and plant their seeds. The seasonal calendar was decidedly less helpful at predicting and marking other events that took place throughout the year.

By the time of the Old Kingdom, the period when the pyramids were built, Egypt had also instituted a civil calendar. The civil calendar is likely to have been based on the movement of Sirius, a star which re-appeared in the sky at about the same time as the Nile would start to flood.

The civil year was made up of twelve months of 30 days, and an additional month of five days, creating a year of 365 days. The lack of a leap year meant that the movement of the stars gradually fell out of sync with the names of the month. As the appearance of Sirius fell back through the calendar, the Egyptians created a Sothic Cycle. Every 1,461 Egyptian civil years, Sirius would return to its place in the calendar.

The Roman Calendar

By the time of the establishment of the Roman Empire, we had several millennia of experimentation completed with various calendrical systems and with multiple different ways of marking time. We had stone circles and stone markings. We had the lunar calendars and combinations of solar and lunar calendars.

We still weren’t getting it right. That the amount of time the Earth took to revolve around the sun couldn’t be counted in whole days. When a civilization couldn’t count an entire day, it meant that calendars in different places and times around the world would regularly fall out of sync with the seasons. If a calendar is out of sync with the seasons — it’s out of sync with the stars and the movement of the moon.

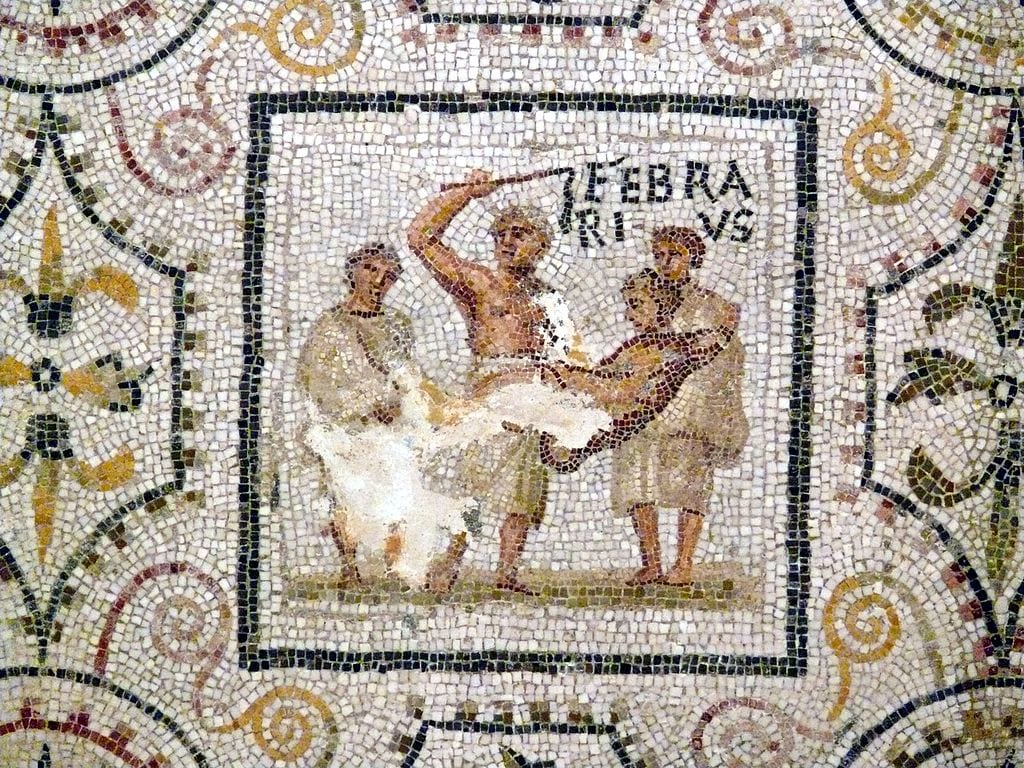

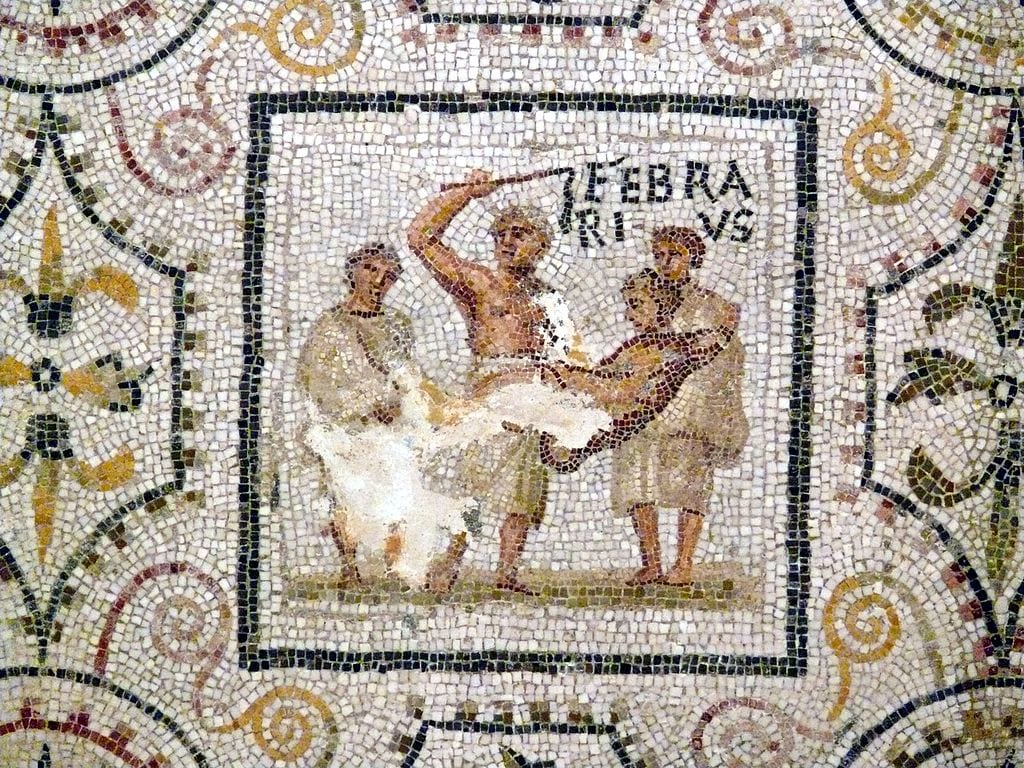

The earliest Roman calendars were little better than most (and look at that tile work!). These calendars, too, started as lunar calendars, tracking the development of the moon over 29.5 days. With the early Roman calendars, they only lost ten or eleven days a year. At the same time, early Rome also had a nundinal cycle derived from the Etruscans. The nundinal cycle was an eight-day week, ending with a market or a festival. Farmers would head to the city to buy and sell goods. Children had no classes on that day, and slave-owners warned their property not to enjoy themselves too much.

Image by Ad Meskens fragment of a mosaic with the months of the year.

A year in early Rome is believed to have been made up of 38 such nundinal cycles, divided into ten months of 30 or 31 days. How the Romans dealt with the remaining days is unclear. Some scholars have claimed that the Romans disregarded them while others suggest that the early Romans practiced intercalation, inserting extra days into the calendar to fill the gap and make sure that the calendar didn’t fall out of sync with the seasons.

Beware the Ides; and the Kalends; and the Nones

The end of the Roman kingdom and the growth of the Roman Republic led to another revision of the calendrical system. Now the Romans were influenced by Greek calendars which divided the year into twelve lunar months, alternating between 29 and 30 days. The Romans, however, gave the third, fifth, seventh, and tenth months of 31 days each. Every other month was 29 days, except February which had 28 days and 29 in each leap year.

Each month, too, was carefully divided. The Romans called the first of the month “kalends,” the origin of the English word “calendar.” They called the day before the middle of the month the “ides,” and the eight days before the ides (or nine days counting inclusively) they called “nones.” Those moments are likely to reflect the calendar’s lunar origins, and mark the sighting of the crescent moon, the quarter moon, and the full moon.

We can begin to see and understand a bit of information about the foundation of the calendar that we use today. In particular, we note the use of an intercalary month in February to keep the months aligned with the seasons. But the Roman calendar did have one interesting difference.

After the establishment of the Roman Republic, control over the intercalation passed to the high priests. By adjusting the number of days in February, they were able to lengthen or shorten the term of office of the consuls they supported. It was as though a political party could determine the length of a year and make the year longer when they were in office. The priests could gerrymander the calendar.

The History of the Julian Calendar

In 48 BC, Julius Caesar proposed a reform to the Roman calendar. The high priests’ willingness to adjust the length of the year in accordance with the rule of their political allies or to skip intercalation if it suited them, meant that the calendar drifted out of alignment with the year. The Second Punic War against Carthage and the Civil Wars, in particular, meant that few people outside Rome knew the current date. Between 63 BC and 46 BC, the calendar had only five intercalary months instead of eight, and none between 51 BC and 46 BC. Historians have called these years the “years of confusion.” Julius Caesar had spent time in Egypt, knew what day it was, and wanted a more conventional way of maintaining the calendar.

After returning from the African campaign in 46 BC, Caesar added two intercalary months between November and December, increasing that year by 67 days. The year had already been increased from 355 to 378 days, so in 46 BC the calendar was now 445 days long.

The reform then added ten days to every year. Two days were added to January, Sextilis (which is now August) and December. Another day was added to April, June, September, and November. February continued to be 28 days. The new calendar removed the previous intercalary month, replacing it with a new leap day placed before the kalends of March. Romans continued to mark kalends, ides, and nones, but the pattern of the calendar that would come to be used by much of the modern world had been formed.

The Naming of the Months on your Calendar

The new calendar spread across the empire and also into neighboring states and client kingdoms, where calendars became 365 days with one leap day, initially every three years but eventually every four years.

The names of the previous months remained mostly unchanged. January honored the god, Janus who symbolizes “new beginnings.” These gods are interesting to study for many reasons, but the god Janus had one head, but two faces. In honor of this god, one face could look forward to the future, and one face looked back to the previous year. Every month had deep reflections, thoughts, concerns, and deliberations to come to a consensus of opinions. The calendar was vastly serious to these people.

February is likely to derive from the Februa festival. March was for the god Mars. The origins of April, May, and June are unclear; but may have been derived from the Etruscan god Apru, and the gods Maia and Juno respectively. An alternative theory is that April comes from the Latin word “aperire,” to open, while May and June are old terms for “senior” and “junior.”

The remaining months were named after their order in the calendar. Quintilis was the fifth month; Sextilis, the sixth; September, the seventh; October, the eighth; November, the ninth; and December, the tenth. The Julian reform pushed the months down the calendar so that December became the twelfth month without changing its name. Quintilis, however, the birth month of Julius Caesar, became Iulius (“July” in English), and Sextilis became Augustus or August.

Other emperors tried to rename months too. Caligula tried to call September “Germanicus” to honor his father. Nero wanted to April to be called “Neroneus.” Domitian wanted October to become “Domitianus.” These names didn’t stick.

The History of the Gregorian Calendar

The Julian Calendar worked pretty well, but it wasn’t wholly accurate. The calendar assumed that a year had precisely 365.25 days in a year. The Earth takes 365.2422 days to revolve around the sun and that difference of eleven minutes every year was enough to push the calendar out of alignment with the equinoxes by about three days every 400 years.

By the eighth century, Saint Bede, an English Benedictine monk, had already noticed that the calendar had drifted by three days. Five hundred years later, Roger Bacon figured that it was a good week or so out of alignment; and by 1300, Dante talked of the need for complete calendar reform.

The drift of the calendar proved a problem for the church. The celebration of Easter was determined by the date of the spring equinox which the church had established fell on March 21. By the sixteenth century, the equinox fell about ten days earlier.

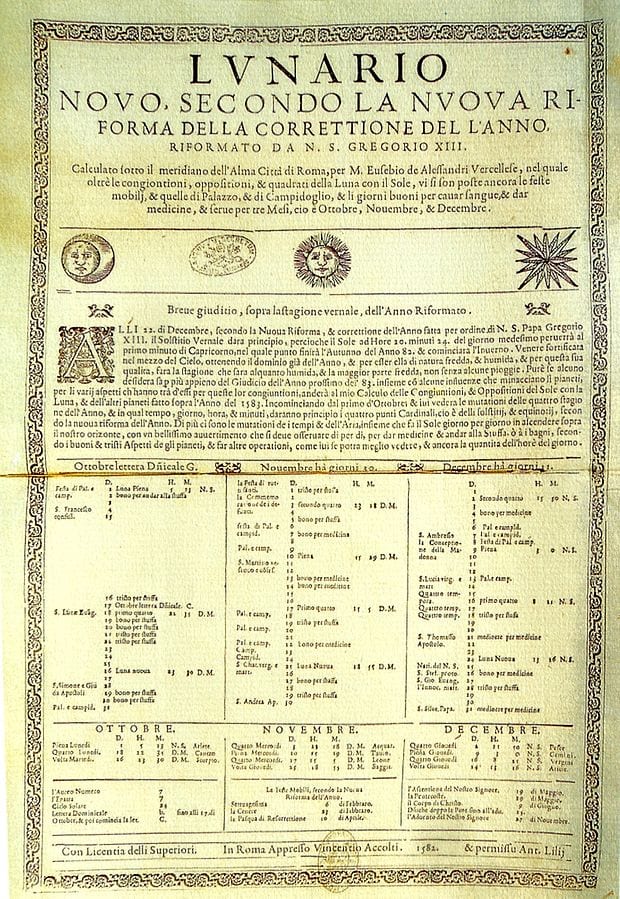

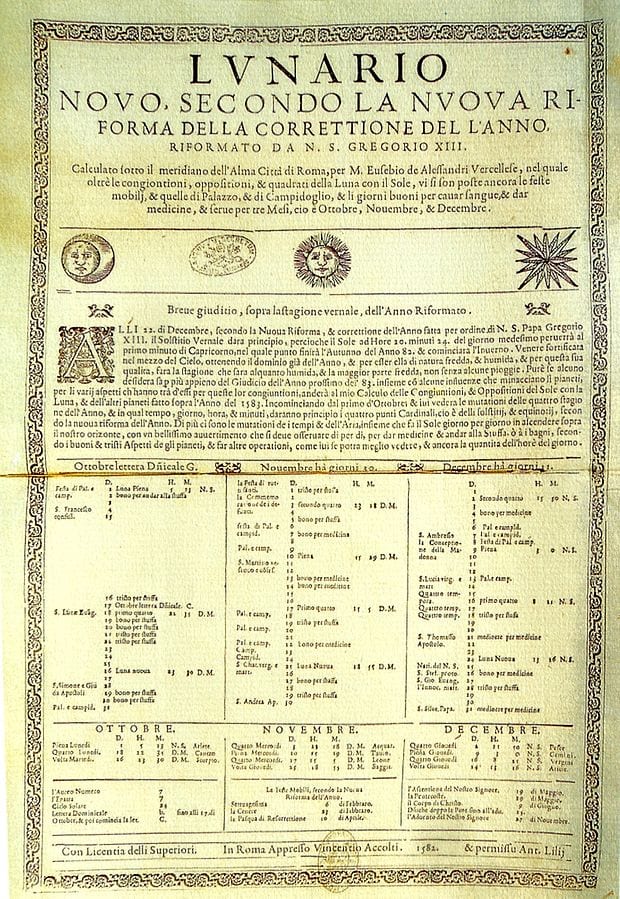

Image: Vatican Library

In 1545, work on changing the calendar got underway. The Council of Trent authorized Pope Paul III to adjust the dates so that the spring equinox matched once again the equinox at the time of the First Council of Nicaea in 325. The Nicaean Council also asked for a new way of keeping time to prevent Easter from drifting through the calendar again.

Aloysius Lilius Fixes the Calendar

Whatever the faults of the calendar, work in the sixteenth century took an incredible amount of time. It wasn’t until 1577 that the reform commission asked mathematicians for their contributions. The winning proposal came from Aloysius Lilius, an Italian doctor and astronomer. He suggested the leap year should first be canceled for the next forty years, allowing the equinox to catch back up with the calendar. He then suggested a new formula to stabilize the calendar.

Instead of adding a day every four years, if a leap year fell on a year divisible by 100, a day would only be added if that year were also divisible by 400. In the year, 1600, one day would be added and would become a leap year, but not in 1700, 1800 or 1900. 2000 was a leap year, but 2100 will not be a leap year. The result would be the addition of a leap day on only 97 days out of every 400, instead of a leap day added every 100 days. These additions and subtractions ensured that the calendar was regularly brought back into alignment.

The new calendar was adopted on Friday, October 15, 1582, during the papacy of Gregory XIII. The previous day, according to the Julian calendar, was Thursday, October fourth. Spain accepted the new calendar immediately, followed by Spain, Portugal, France, Poland, Italy, the Catholic Low Countries, and Luxembourg. The Kingdom of Bohemia adopted the calendar two years later. Prussia accepted the calendar in 1610. Protestant countries were slower to adopt the calendar, concerned that it would bring their countries closer to Rome. Britain didn’t choose the Gregorian calendar until as late as 1752. Greece waited until 1923 to adopt the calendar, and Turkey until 1926.

The Gregorian calendar repaired the Julian calendar’s error of one day every 128 years, replacing it with an error of one day every 3,030 years. Sir John Herschel, a nineteenth-century English mathematician, suggested increasing the calendar’s accuracy by not making the year 4000, and its multiples, a leap year. He was ignored.

Local Calendars Still in Use

We’ve moved through several thousand years of history. We’ve seen calendars change from stone arrangements used to mark the solstice and predict the return of migrating animals; through the tracking of the stars and the counting of months. Mostly what we’ve seen through the metamorphous of the calendar, is various cultures and empires struggling to produce a way of counting days and months in a year. Their difficulty was taking into account the extra quarter-day that the Earth uses to get back to its starting point. Without taking that time into account, they’d see the calendar slip through the year. We’ve also seen some creative names for the months those calendars have come up with.

The introduction of the Gregorian calendar set the seal on the calendar’s development. Lilius’s correction, introduced during the papacy of Gregory XIII, meant at last that the year was always accurate and never needed correcting—or at the very least, only occasionally. The calendar’s spread across Christendom, and from there around the world, means that the globe now shares a single way of marking time.

The Continued Use of the Julian Calendar

The calendar is not the only way to mark time. The Gregorian calendar isn’t the single calendar still in use. While everyone might be able to find the same date on the same calendar, around the world, people still use other calendars. Even in Europe, the Gregorian calendar didn’t reach everywhere. On the autonomous province of Mount Athos in Greece, the Julian calendar still reigns supreme. The province is made up of twenty Orthodox monasteries, and entry is forbidden on the island to women.

Orthodox churches, if not Orthodox countries, remained with the Julian calendar. These countries even rejected a lunar calendar that would match the Gregorian calendar until the year 2800. The calendar was suggested at a synod (congress, committee), in Constantinople in 1923. Apart from the Estonian and Finnish Orthodox Churches, Orthodox churches continue to celebrate their Christian festivals according to the Julian calendar, and not the Gregorian calendar. Other areas and religions have also stuck with their traditional calendars.

The Hebrew Calendar

Israel uses two calendars: the Gregorian calendar; and the Hebrew calendar. The Gregorian calendar will be used for all secular activities, for fixing the time of the school breaks, for arranging business meetings, and for celebrating birthdays. But the dates of religious festivals — and there’s a Jewish holiday almost every month — are determined by the Hebrew calendar. Similarly, the Jewish calendar is used to determine the portion of the Torah to be read each Shabbat. It’s also used to fix the dates of memorials to commemorate the death of a relative.

The Hebrew calendar is strongly influenced by the Babylonian calendar, a result of the Jewish exile in Babylon which ended in the sixth century BCE. The Bible suggests that before the exile, the Hebrew calendar consisted of ten months of thirty days each. The Bible only names four months: Aviv (which means “spring”); Ziv, Ethanim, and Bul. These names are believed to be Canaanite. After the Babylonian exile, the names of the months more closely matched the names of the months of the Babylonian calendar.

One notable difference between the Gregorian calendar and the Hebrew calendar is how the days are measured. The Hebrew calendar regards a day as beginning at sunset. Shabbat starts when the sun sets on Friday evening. The Shabbat day ends when the sun sets the following day.

No less important though is how the months are measured. The Gregorian calendar is solar. It’s based entirely on the relative position of the sun to the stars. The Hebrew calendar is a lunisolar calendar, meaning that the months are based on lunar months (taking into consideration the phases of the moon) — and the years are based on solar years. This calendar has twelve lunar months that last either 29 or 30 days.

The Buddhist Calendar

Also adhering to the lunisolar calendar is the Buddhist calendar, primarily used in mainland Southeast Asian countries of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand — with many many variations and versions in countries around the world. The traditional Buddhist calendar is mainly used for Theravada Buddhist festivals, and there is no longer an official Buddhist calendar status anywhere.

The Buddist calendar keeps track of the movements of both the Moon and the Sun, and mostly follows the Hindu calendar. This calendar is somewhat inaccurate when reflecting the length of a solar year and the onset of the seasons because of the “sidereal year,” and the 19-year cycle use to determine the distribution of leap years based on the length of a tropical year.

The Metonic Cycle

A solar year is eleven days longer than the twelve lunar months. These eleven days put the Hebrew calendar out of sync with the solar calendar. Without correction, the holidays would drift out of alignment with the seasons. The solution came with the addition of leap months. The Hebrew calendar doesn’t add leap months every four years, like the Gregorian calendar, but seven times every nineteen months.

The Metonic cycle is the work of Meton of Athens in the fifth century BC. Following the Babylonians, Meton noticed that nineteen years is almost exactly equal to 6,940 days. Adding the seven additional months, over nineteen years would be enough to correct the calendar.

Using the Metonic cycle isn’t the only complication. The calendar can also change to make sure that Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, does not fall immediately before or after Shabbat. The month of Kislev can lose a day, and the month of Cheshvan can add a day. The result is a reasonably complex calendar that many people generally ignore. The Hebrew dates will appear at the top of newspapers, but otherwise, people basically use these calendars to mark Jewish holidays.

The Islamic Calendar

The Jewish Calendar goes out of its way to remain in alignment with the solar calendar. The calendar also adjusts the lengths of the months. A holiday fixed by month shouldn’t clash with a holiday fixed by week. The Islamic calendar takes a much easier route. It doesn’t correct at all. It consists of twelve lunar months, which together number 354 or 355 days. That will consider the difference to the 365.25 days of the solar year. This calculation means that the Islamic calendar drifts by about ten days every year. The cycle only repeats every 33 lunar years.

The result is that Ramadan, the month of fasting, can take place in the summer or winter, depending on the position of the calendar. That may be why most Islamic countries only use the Islamic calendar for religious holidays and not for civil events. These public events are marked using the Gregorian calendar. The exceptions to the “civil event rule,” are the countries of Iran and Afghanistan, which use the solar Hijri calendar.

The Hijri Year

The Hijri year is also the foundation of the Islamic calendar. This calendar came about in the era in which Muhammad and his followers traveled from Mecca to Medina to form the first Muslim community. That event took place in 622 AD and marks the start of the annual count. According to the Islamic calendar, 2019 in the Gregorian calendar is the year 1440. (The Hebrew calendar makes the year 5779.)

The Islamic calendar contains twelve months, each of which begins with the start of the new lunar cycle. Each of the months also has its own significance. The months of Rajab, Dhu al-Qa’dah, Dhu al-Hijjah, and Muharram are considered sacred. Ramadan is a month of fasting. Shawwal means “raised” and is said to be when camels would be in calf; (with calf), meaning they are pregnant. Sha’ban means “scattered” and marks the time when Arab tribes scatter to find water. Dhu al-Hijjah is when the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, is performed.

Two Countries, Two Months

Another challenge the calendar faces and creates is that most Muslim countries declare the start of a new month by observing the rise of the new moon. Each country will make its own observation. But the sun sets later as you head west, and the conditions may make the moon easier or harder to see in one particular place than another. The result is that two Muslim countries may be in different months at the same time.

There have been plans to try to get around the problem. Malaysia, for example, is one of several countries that start the month not when they see the new moon but at sunset on the first day that has moonset after the sunset. Some representative bodies have declared an intention to use calculations instead of observations to determine the months, but not all associations have agreed, and not all those that have declared an intention have carried the purpose out.

It’s a complicated business, and that means that not only is the Islamic calendar out of alignment with the solar year and the Gregorian calendar. The Islamic calendar is also sometimes out of alignment with other users of the Islamic calendar.

The Chinese Calendar

Image: Karen Arnold

The Chinese calendar is less a way of keeping time than a method of assigning personal attributes based on the date of their birth. The Chinese calendar is a zodiac calendar. The giant celebration that takes place at the start of the year, usually around February, makes this calendar worth mentioning. The Chinese calendar is one that makes more than a billion people stop and take a new year holiday is too big to ignore.

Although the Western astrological calendar matches twelve signs to the constellations that are in the sky at the time of someone’s birth, the Chinese calendar cycles twelve animals through the years. An old story explains the order of the animals.

How the Chinese Calendar Got its Order

The Jade Emperor declared that the first animal to cross a river would be the first in the calendar. The second animal would be placed second, and so on. The cat and the rat asked the ox for a lift. When the ox reached the bank, the rat pushed the cat into the river. The rat then jumped off the ox and came first. The tiger arrived after the ox, followed by the rabbit which had jumped from rock to rock. The rabbit then leaped onto a log that was blown to the shore.

The dragon came fifth. This dragon had stopped to bring rain to a village, then he blew the rabbit’s log to the shore. The horse arrived, with the snake clinging to its hoof. The snake took sixth place, the horse seventh. The rooster had found a raft, which she rode with the monkey and the goat. The goat was eighth, the monkey ninth, and the rooster tenth.

What Happened to the Cat?

The dog had stopped to play in the water, so he only came eleventh, but he still beat the pig which had stopped for a meal then had fallen asleep. But even the pig did better than the cat. The cat had drowned when the rat pushed her into the river.

It’s a beautiful story (except for the cat), and the Chinese calendar plays a role in modern Chinese life. This calendar marks the country’s biggest holiday, and people will know under which animal they were born. What they might not know, though, is that each sign also matches a month of the year and a season of the year — like the Western astrological signs.

The tiger, for example, corresponds with Aquarius and Pisces and runs from early February to early March. The Dragon crosses Aries and Taurus and runs from early April to early May. Even the days of the week align with zodiac animals: Monday with the goat; Tuesday with the dragon and pig; Wednesday with the horse and rooster, and so on. It’s mostly the Chinese calendar that tells you when to light the fireworks and which kind of decorations to put up in February.

Mesoamerican Calendars

So far, we’ve focused on calendars that were created in Europe and Asia, but Mesoamerica also formed indigenous calendrical systems. Some of these calendars are still in use today. Many of these calendars are not widespread, but some groups in the highlands of Guatemala and some regions of Mexico continue to use these ancient calendars.

That’s a problem because the calendar in most common use across different Mesoamerican cultures is a ritual calendar. This calendar lasts 260 days and has no relationship with any farming cycles or astronomical movements.

Image by El Comandante of the Aztec Calendar

The origin of the calendar isn’t clear. Izapa, the site of a 3,200-year-old settlement in Mexico, experiences 260 days between the sun’s two zeniths each year. The site may be one source of the calendar, but it could also be the result of the Maya civilization playing with the numbers thirteen and twenty; which they liked. Another theory associates the calendar with the length of a human pregnancy, but the origin of this practice still isn’t entirely clear.

The Mayans called the calendar “tzolk’in.” They named twenty days which they associated with thirteen numbers. There was no day or month, but each day had a name and a number, and the calendar took 260 days to work through the complete cycle. Each day also aligned with a natural phenomenon, such as a crocodile or death. Glyphs (like a hieroglyph or symbol, or picture) on stone carvings, represent days.

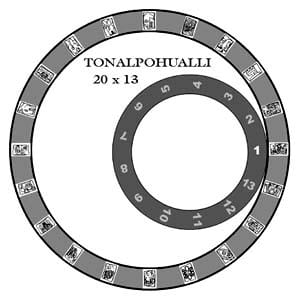

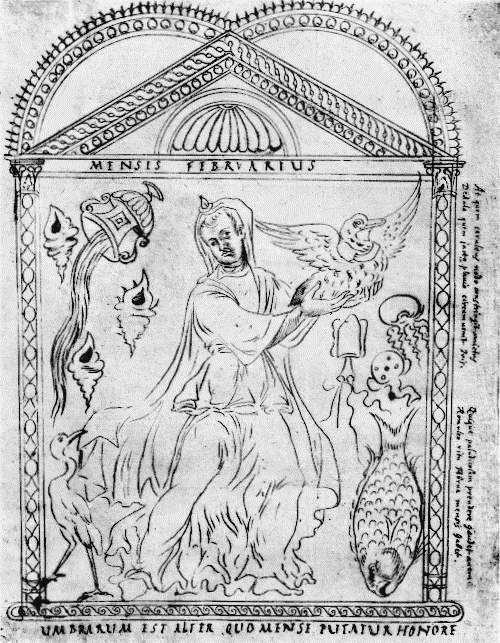

The Aztecs used a similar calendar called “tonalpohualli,” which means “count of days,” in Nahuatl.

Image: Richard Graeber

The Aztec calendar, too, combined a 20-day cycle called “veinenas” with a 13-day period called, “trecenas.” The days had glyphs associated with Aztec deities such as Quetzalcoatl and Mayahuel.

The tonalpohualli contained only 260 days. But the Aztecs had a second calendar that came a little closer to the solar calendar. The “xiuhpōhualli” consisted of eighteen months each lasting 20 days, with a five-day period tacked onto the end. That brought the year to 365 days. Xiuhpōhualli would align with tonalpohualli every 52 years.

Modern Calendars

We’ve seen that there’s been no shortage of calendars over the last few millennia. Calendars have always been important in civilizations wherever they have existed in the world. We want to know what time it is, and where we fit in the universe of time and space. We can see that the Gregorian calendar has become widespread. It’s international and provides a way for anyone anywhere to synchronize times with anyone located anywhere else on the planet. Even though several other calendars have remained in use (about 40 differing calendars), these calendars mostly mark the times of religious events rather than secular occasions.

The format in which all calendars have been presented have changed over time. Early man used the first calendars to mark the solstice and the passage of migrating animals in stone. The stone made their calendars hard to change or adapt to changing circumstances. Stone made their calendars hard to move around. If you wanted to know how close the year was to mid-summer or mid-winter, you needed to make a pilgrimage to Stonehenge or Warren Field. It wasn’t very convenient.

Gratefully, that brings us to today’s calendars and their ease of use. Although some designers have become very creative, using blocks to mark dates, days, and months, most calendars are either paper or digital.

Paper Calendars

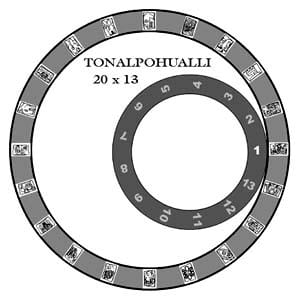

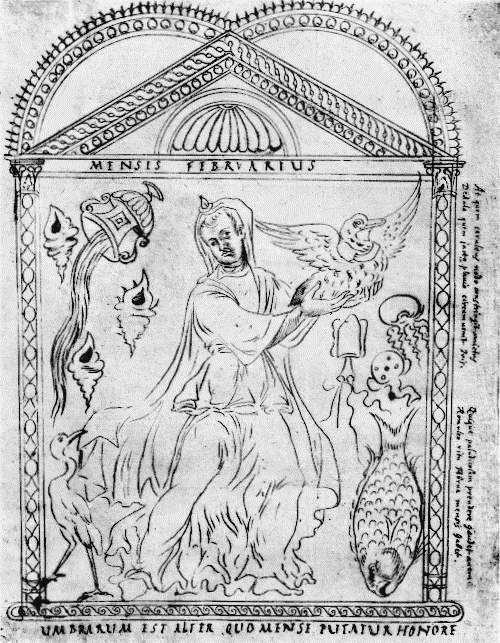

Image: Chronography of 354

The use of parchment, and eventually paper, made creating and using calendars a great deal more convenient. One of the earliest paper calendars is the Chronography of 354. A wealthy Roman Christian, called Valentinus, commissioned Furius Dionysius Folocalus to draw and write the calendar (as they knew it) in the fourth century.

The original didn’t survive, but scribes copied the calendar through to the ninth century, with further copies made in the seventeenth century.

The Chronography of 354 calendar is more of an almanac than a calendar; it lists events that take place during the year and includes Christmas. That holiday inclusion is a notable addition in a calendar produced merely as Rome was shifting from pagan beliefs to a growing Christianity. The calendar is also heavily decorated, with drawings of the emperors; of personifications of the cities of Rome, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Trier. Seven planets and their orbits dot the calendar, and the signs of the zodiac are included. Dates marked in the calendar, other than Christmas, also include the dates of Easter from 312 to 411 AD; and the commemoration dates of popes and Christian martyrs.

The Calendar of Carthage

The Calendar of Carthage was a beautiful piece of work. But it shows that in the paper calendar’s earliest forms, it still marked set events rather than any record personal habits. The same usage of the calendar continued through the centuries that followed. The Calendar of Carthage dates to the sixth century and includes the commemorations of all of the bishops of Carthage from Gratus (c.343-348 AD) to Eugenius (481-505 AD).

The Carthage calendar also contains a long list of feast days for various martyrs, bishops, and saints. The month of May alone has ten such days, while January has eleven. December has a feast for “Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God” on December 25th. But, with so many saints to mark and commemorate, it’s no wonder that the church needed to create almanacs to keep track of them all.

The idea that people needed calendars — or planners — to keep track of their own personal events is relatively new. Many of the earliest calendars would have been almanacs with extra space or pages for people to make their own entries. Most of these relics are lost. Once someone has used an almanac, there’s little point in keeping it.

Washington’s Diary

One of the earliest surviving paper calendars though belonged to George Washington.

His almanac also functioned as a local guide. In addition to telling him the times of sunrises and sunsets each day, it also told him the names of local inns, the postage rates in various locations, and even made predictions about the weather. (It’s not clear how accurate those predictions were.)

Washington, though, would add his own blank pages to his almanac. Each day, he wrote down the names of his visitors, the places he rode, and the people who dined with him. In effect, the almanac had become a diary, a record of what he had done. Although the calendar hadn’t yet become a record or a reminder of future events, it had expanded from a list of religious events.

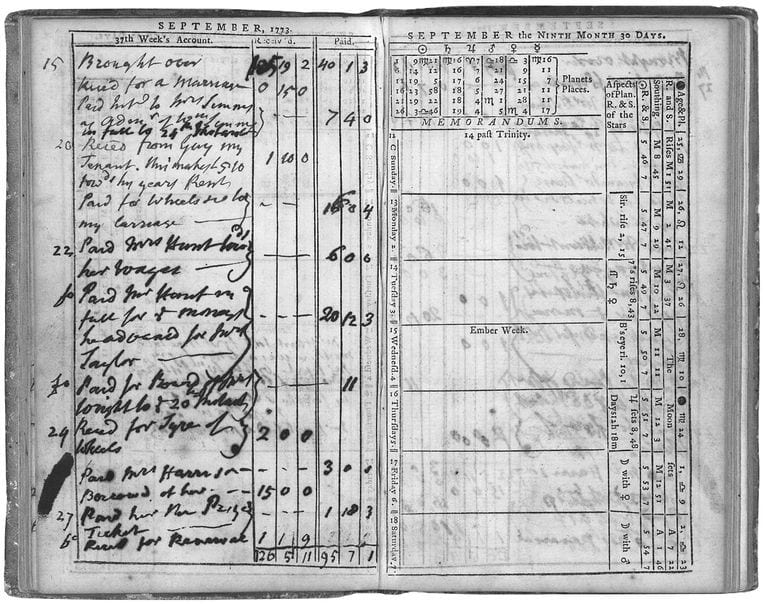

Aitken’s Calendar

Robert Aitken, a publisher in Philadelphia, published the first proper planner in the US in 1773. It looked more like an account book than a calendar. One page had space for memoranda associated with various weeks of the month. The other page left space for the week’s accounts. Customers would write down what they spent and earned each week so that they could keep track of their finances.

Image: Collection of Molly McCarthy

Aitken’s planner didn’t take off, but the ability to scroll through the days and weeks to come and schedule planned events had already started. Aitken’s planner provided a way to record past events. This planner acted as a reminder for regular annual events such as religious holidays, but it also offered space for people to write down the activities or events they would be attending in the future.

By 1850, the ability to plan ahead on paper had become widespread. An 1844 list of taxpayers included one Bostonian with $100,000 in taxable wealth. His job? Manufacturing blank books, like calendars.

The Soldier’s Calendar

Upper-class men with busy lives and lots of riding companions tended to buy those calendars. By the time of the Civil War though, everyone was carrying calendars and planners that they could use to record their activities and organize their lives. The Boston Globe has described Union soldiers carrying their Standard Diary or their American Diary into battle.

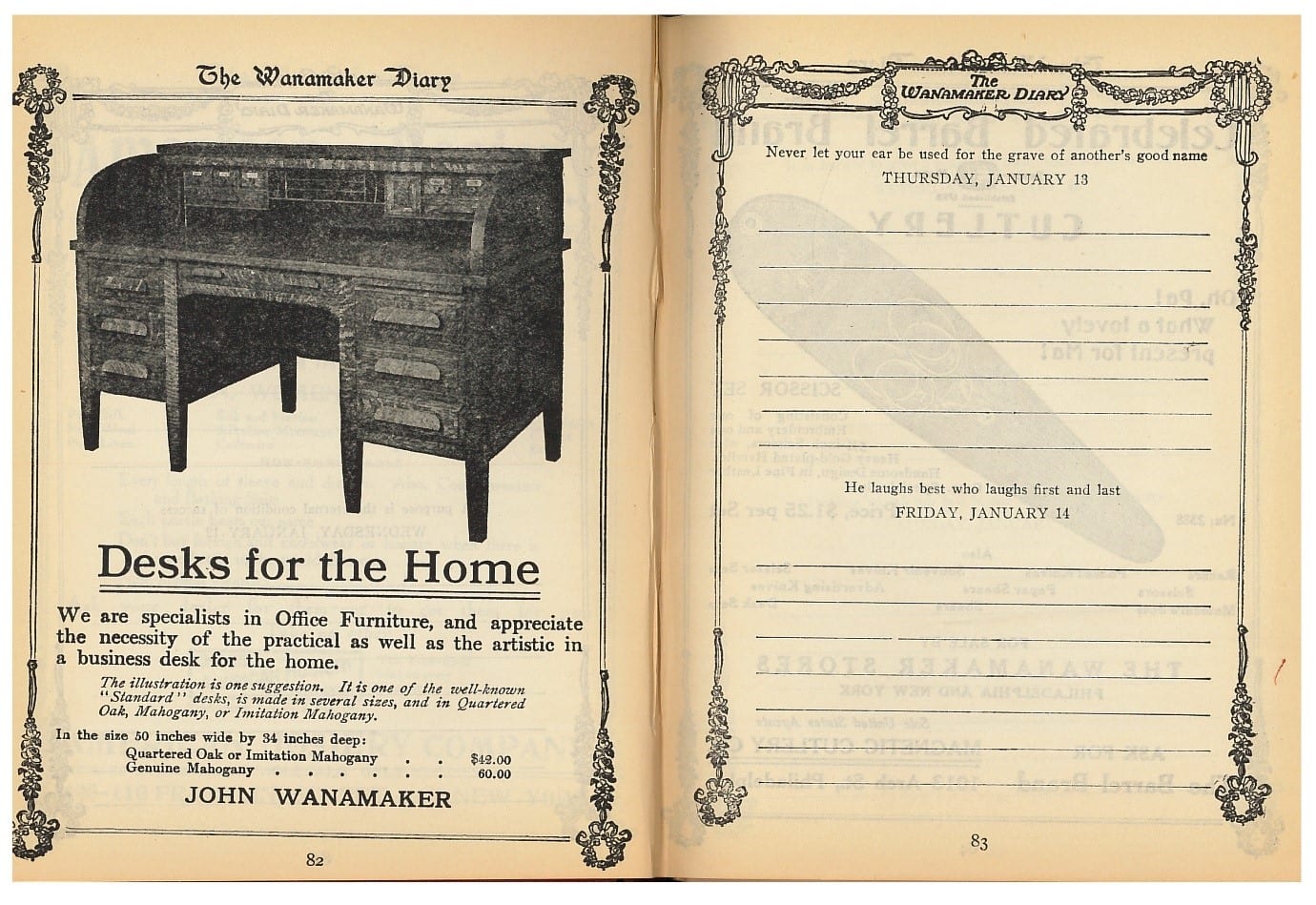

One change was in the purpose of the calendar. By the start of the twentieth century, the calendar had become an essential tool, a way to make good use of one’s time instead of wasting it or leaving time alone — to fill by itself.

So vital had the diary become, and so widespread in its use, that in 1900 department store owner John Wanamaker gave a diary out for free with his catalog. The calendar was surrounded by advertising so that people would fill in their appointments alongside pitches for desks and linen.

The Wanamaker diary also contained a list of events taking place around the world over the coming year and included inspiring quotes for each day. With the Wanamaker diary, the format of the modern paper diary was largely complete.

The remaining development was relatively small. Despite the rise of calendars supported by advertising and branding, stationery stores continued to sell paper calendars and planners. Businesses continued to give away small calendars, and calendars could be attached to magnets that customers could stick to their fridge doors.

The real threat to paper calendars didn’t come from freebies. Nor did it come from a backlash against Pirelli or Sports Illustrated calendars in the workplace. The paper calendar seems to be meeting its demise from the rise of digital calendars which have brought a whole new level of functionality to calendars.

Digital Calendars

Paper calendars have always had their limitations. First, they were single-use. When the year ended, you had to go back to the shop to buy a new one — though, the paper calendar can provide a valuation record. The space inside them is minimal. Although calendars come in different sizes, people need to choose a compromise between cramped writing in a mobile notebook or generous space in a calendar that is difficult to carry.

Most importantly, though, users can’t readily share a paper calendar. There is only a one-off, or one-ever copy available. A group of people trying to organize an event have to pull out their paper calendars, then flick through pages until they all find an empty space.

Digital calendars have solved all of these problems. A digital calendar is permanent, and users can automatically renew their subscriptions. The size of the screen is the only limit, and if the screen is too small, a line will explain how many more appointments have been added. Calendars have become effectively unlimited and non-limiting.

Calendars and Schedules

Digital calendars are actually templates over which people lay different kinds of schedules. These schedules can be religious holidays, sports, games, school events, birthdays, or anything else an individual wants to do for work and life.

A digital can even be other people’s schedules. Digital calendars can be shared, and the amount of sharing can be controlled. Users can choose to let colleagues see their work schedules to make booking meetings easier. A person can show clients only when they’re available without revealing what they’re actually doing. The individual can share everything with spouses so that when one of them schedules a babysitter or makes a restaurant reservation, it’s entered into both partners’ calendars automatically.

Although digital calendars originally came in a variety of forms, most people use one of three platforms.

It’s difficult to say how many people use Google Calendar. The app has been installed on Android devices more than a billion times. It helps, of course, that a version of the calendar comes already installed with every Android device. Anyone with any type of Google account has access to the calendar. For Google itself, the entries made on the calendar can become a giant source of data. It gives the search company an idea of a user’s schedule, what they do, and where they go.

For users, it’s also convenient. Entering events on the calendar is simple both on mobile phones and on desktops. The synchronization is almost instant, and you can also add reminders and even tasks. The synchronization with Gmail means that emailed tickets create events automatically on the calendar. Google Calendar even generates illustrated headers based on keywords in the event. Write “Concert” when you create an event, for example, and Google will give you a pre-made illustration of musical instruments. It’s a little creepy but also quite nice.

Apple supplies a calendar too, but it’s aimed at users of either its iPhones or its Mac computers. Or both. The primary calendar in iCloud is relatively limited. For iPhone users though, and there are plenty of them, the Apple Calendar is a default choice if only because it comes installed in the phone.

But this calendar has plenty of drawbacks. There’s no automatic event creation from emails or iMessages. The design can be challenging to read and use. Inviting people to events that you’ve created can be more fiddly than it should be. You might find that you have to manually add an email address to your contact list before you can share a calendar event. It shouldn’t be that hard.

The only advantage of Apple’s calendar is that Apple doesn’t suck up data. Google gives better functionality on its calendar but at the price of privacy.

If Apple’s digital calendars can be too simple, Microsoft’s are painfully complex. This calendar is built into Outlook or Microsoft Exchange are better thought of as enterprise time management tools. It’s easy to imagine office managers using them to arrange meetings and book rooms. It’s harder to imagine anyone else using them to remind themselves of their nephew’s birthday or to scrawl in anniversary reservations.

Most digital calendars let you layer on schedules. Microsoft also lets you place multiple calendars side-by-side, and create some fairly complex events. The amount of functionality that Microsoft has squeezed into its calendar is impressive. But it’s really a calendar for work not for social use. The absence of a Microsoft phone, in particular, means that it’s really a digital calendar for the workplace on your computer, at work.

Conclusion

The calendar has come a long way over the last few thousand years. Early calendar makers fixed the problem of measuring annual time in a year that doesn’t have an even number of days. We’ve created one calendar that’s universally used even as other people use different calendars for religious and cultural events.

We’ve figured out how to plan ahead and describe events that we know are coming up. And we now have a way to keep our calendars with us at all times, to share our events, and fill them up endlessly, complete with reminders and notifications.

But we’re still not done. While companies like Google and Microsoft have built complex time management platforms, some functions are still tricky. It’s always hard, for example, for people to make bookings with staff at companies or healthcare centers. Finding spare time among a group of friends trying to arrange a time to meet can be a challenge. Selling time slots in a calendar isn’t automatic or available on any of the main digital calendar platforms.

We’ve come a long way from stone circles marking the solstice, but we’re not done with calendar development yet. 2023 shows promise for more technology and advancement in technology.

Updated February 3, 2023

John Rampton

John’s goal in life is to make people’s lives much more productive. Upping productivity allows us to spend more time doing the things we enjoy most. John was recently recognized by Entrepreneur Magazine as being one of the top marketers in the World. John is co-founder and CEO of Calendar.