Language, Interpretation, and Translation: A Clarification and Reference Checklist in Service of Health Literacy and Cultural Respect

“The first skill of a great translator is humbleness, to be a servant. Once you are a servant, you may be lucky to be called a master of your craft. And, you need the humbleness to understand your original, to be part of it—then also the practical humbleness to get someone who knows more than you to check your work. That collaboration is very enriching and very rewarding—a good way of ensuring you produce a decent translation.”

— Marco Sonzogni, n.d.

“Translation is not a matter of words only; it is a matter of making intelligible a whole culture.”

— Anthony Burgess [8]

Introduction

Language, interpretation, and translation are becoming increasingly critical parts of practicing medicine across the United States. However, these areas often aren’t considered before the patient is sitting in front of the clinician—and at that point, it is too late. Interpretation, translation, and regard for language need to be incorporated across the clinical workflow and deeply considered and planned for well in advance of the patient seeking care.

This manuscript describes complex problems of language, interpretation, gesture, and translation and recommends solutions. Simply providing definitions for the topics discussed does not provide an effective message for understanding the human context of language—especially in medical settings.

Recently, NAM Perspectives published “A Journey to Construct an All-Encompassing Conceptual Model of Factors Affecting Clinician Well-Being and Resilience” [7]. This constitutes an important effort to create a more holistic view of the provider. The authors of this manuscript contend that this same 360-degree model of the clinician could be matched with a 360-model of an interpreter or translator and a 360-degree model of the patient’s stressors. Using these two additional representations could provide a better understanding of all factors at play.

During our careers in linguistics, communication, and interpretation, and from our work in health literacy, it has become clear to the authors that many health professionals lack a clear resource to help them navigate the multilingual reality of health care in the United States. In this manuscript, we offer linguistics, gesture, health literacy, health communication, and cross-cultural experience as lenses through which to consider cross-discipline communication. We also offer a checklist to guide providers when they do not share a common language with their patients.

Scope of Language Challenges

Providing a free flow of accurate information and a clear understanding about how to improve human health and prevent disease depends upon spoken, written, or signed words. Central to effectively sharing this knowledge is knowing how to meet people in a fair and trustworthy way while respecting the complexities and values within and among varying cultures.

A core principle underlies all communication: humans communicate symbolically. Even the languages people speak, write, or sign are, at their essence, symbols. Burke described humankind as a “symbol-using animal” whose reality has actually been “built up for us through nothing but our symbol system” [9].

The issues of language access and effective communication are much more complex and require much more attention than what occurs when people state that they need to “get someone to translate it” or “find someone who speaks some Farsi or Spanish.” Communication is difficult, and communicating about often frightening and overwhelming health issues is even more complex. When a health care provider does not speak the same language as those being treated, relationships can quickly become strained, important pieces of information can be lost, and gestures or turns of phrase can be misinterpreted. These lapses in language can change the course of someone’s life.

The number of languages spoken in the U.S. compounds this complexity. Historically, 39 languages had been tracked through the American Community Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau. But, in 2015 the bureau reported that more than 350 languages are spoken and signed at home in the United States. These data also included more than 150 Native American languages (such as Apache and Yupik) as well as additional information about language use in 15 metropolitan areas. In the release, Erik Vickstrom, a Census Bureau statistician, noted that “in the NY Metro area more than a third of the population speaks a language other than English at home, and close to 200 different languages are spoken.” He added, “Knowing the number of languages and how many speak these languages in a particular area provides valuable information to policymakers, planners, and researchers” [22]. These data also help to give context to the increasing complexity in navigating the health care system.

The challenge and necessity of translation and interpretation in health care are illustrated in Flores’ concrete 2006 New England Journal of Medicine article on language barriers and his systematic review of the impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care in the United States. In this perspective, Flores notes that “the provision of adequate language services results in optimal communication, patient satisfaction, outcomes, resource use, and patient safety” [13].

Flores describes, with direct quotations of the interactions, the problematic exchanges that occurred when a 12-year-old Latino boy arrived at an emergency department with his mother and met with a physician who spoke little Spanish. Since an interpreter was not available, this minor “acted as his own interpreter.”

The physician misinterpreted when the mother stated that her son was dizzy, thinking the mother said that her son looked yellow. When the physician asked the boy about this, his mother responded, “You were dizzy, like pale,” and the boy reported to the physician that his mother said, “Like I was paralyzed, something like that” [13].

The confused communication among the boy, his mother, and the physician presented very real safety issues and could have resulted in, for example, a missed diagnosis for juvenile diabetes. The authors encourage readers to review Flores’ perspective in full. This excellent resource demonstrates the challenges of, errors in, and outcomes of, language services experienced by physicians and patients alike in the medical setting.

The significance of Flores’s paper was recognized in a contemporaneous editorial in Oncology Nursing Forum by Caroll-Johnson, “Lost in Translation” [10]. Carroll-Johnson concluded that “As the world shrinks and our communities become more diverse, we must be prepared to address these dilemmas with real solutions and not rely on middlemen, women, or children lacking in understanding to do our work for us.”

Reporting on an additional medical setting, outpatient practice, Jacobs and colleagues cite and describe the medical and financial impact of one catastrophic missed interpretation [25]:

On his initial medical history, a Spanish-speaking boy aged 18 years, of Cuban descent, presented with abnormal mental status complaining of “intoxicado.” An untrained interpreter understood this to mean that the boy was intoxicated – though in the Cuban dialect, the boy was actually saying that he was “nauseated.” He received care for a drug overdose attributed to substance abuse but developed paraplegia, subsequently found to be due to a ruptured intracranial aneurysm. The case led to a malpractice lawsuit with a $71 million award to the plaintiff. [26,27]

The authors also review current law, regulation, and policy and the comparative costs of interpreter services and systems in outpatient practice.

As our nation becomes more multicultural, the challenges will become only more complex. The time to address language, interpretation, and translation as critical parts of the health system is now.

Interpretation and Translation: Defining Terms

People often believe that interpretation involves spoken language and that translation involves written language. While these definitions may differentiate the two terms in a general way, there is actually a great deal more to each concept, as we describe below.

Interpretation

Interpretation involves two essential characteristics.

First, it involves the rendering of live utterances in one language to live utterances in another language. The “source language” is the language of the speaker (or signer). The “target language” is the language of the receiver of the interpretation. Interpreting necessarily involves one of three possible dyads: (a) spoken source language and spoken target language, (b) spoken source language and signed target language, or (c) signed source language and signed target language.

Second, interpretation, being a live act, necessarily involves an immediacy not characteristic of translation. That is, the interpreter has to process a piece of speech and render it—either simultaneously or consecutively—into the other language, without the opportunity to consider alternative renderings.

Simultaneous Interpretation

In an example of simultaneous interpretation, the patient speaks (or signs) in their source language, and the interpreter speaks aloud (or signs) what is being said in the target language for the health provider. The interpreter is, at the same time, comprehending the next part of the source’s message.

This is complex. Different interpreters will vary in their delay between the uttered (or signed) discussion and their rendering of the message. The interpreter receives, produces, and converts at the same time. In this example, the interpreter will reverse immediately to simultaneously interpret the information from health care provider to the patient. Unlike in most health care settings, informal presentations, such as a conference, this might involve the speaker using a publicly transmitted channel and the interpreter using a private channel that can be heard only through earphones.

In interpretations between a signed language and a spoken language, simultaneous interpretation is common, because the vocal-auditory channel and the gestural-visual channel do not compete. In the health care environment, positioning of the patient, interpreter, and provider are of great importance and should be carefully planned.

Under any conditions, simultaneous interpretation presents linguistic and cognitive challenges. The results sometimes suffer from inaccuracies not found in other forms of interpretation that allow for greater time delay between the produced utterance and the rendered interpretation.

These difficulties occur not only in spoken language interpreting but during sight translation (on-the-spot translation from documents or directions provided during the visit) that are also interpreted to the patient.

In all cases, the quality of simultaneous interpretation will be improved if the interpreter has access to the text or to accompanying electronic media ahead of the actual event. In medical settings, such access may not be possible, so the pace of simultaneous interpretation may need to be slowed to ensure greater accuracy.

Consecutive Interpretation

In an alternative form of interpretation, called consecutive interpretation, the sender produces (or signs) a short utterance (perhaps a sentence or two) and then pauses while the interpreter renders these pieces into the target language. Upon completion of the interpretation, the sender produces the next short piece of language.

Take this example passage: “I am going to explain the side effects of this medication, which include possible shortness of breath, nausea, dizziness, and anxiety. So, if you experience any of these, call me or go to the emergency room.” Consecutive interpretation would create pauses that are helpful to both the patient and the interpreter. “I am going to explain the side effects of this medication [PAUSE], which include possible shortness of breath [PAUSE], nausea, dizziness, and anxiety. [PAUSE] So, if you experience any of these, call me [PAUSE] or go to the emergency room.”

Consecutive interpretation can be more precise and accurate than simultaneous interpretation because it gives the interpreter more time to seek an appropriate rendering and does not involve the cognitive challenge of undertaking the two tasks of listening and rendering at one time (as in simultaneous interpreting). It can also be more time consuming because each communicator must wait for the interpretation to be completed before initiating the next “turn.”

Translation

Translation involves movement between the written forms of two languages. It is important to acknowledge that there exist translations for unwritten languages [e.g., the endangered tribal language of Coeur d’Alene or to American Sign Language]. There are also translations between differing sign languages. Sometimes misunderstood, it is important to note that sign language is not universal.

More precisely, translation tends to involve movement between a recorded form of one language into a recorded—not necessarily the same form— of another language. In this sense, “recorded” could include written text, audio recordings of spoken language, or video recordings of either spoken or signed languages.

The essential characteristic of translation is that it tends not to be “live.” It involves longer time spans between the source production and the rendering into the target language. The time difference provides the opportunity for consideration of alternative translations, research into previously produced translations, assistance from automatic translators by computer, and revision of the final target production. Translation differs from interpretation not because it produces different materials, but because it offers the opportunity to consider the input and output provided since the target production is “unglued” or separated in time from the source material.

As Youdelman notes, “The most qualified translators are those who write well in their native language and who have mastered punctuation, spelling and grammar. Translators know how to analyze a text and are keenly aware of the fact that translation does not mean word-for-word replacement, but that context is the bottom line for an accurate rendition of any text” [24]. The best translators understand the nuance and connotative power of both languages and understand the level of diction that is appropriate to the texts and the audiences.

Sight Translation

Sight translation is the “translation of a written document into spoken/signed language. An interpreter reads a document written in one language and simultaneously interprets it into a second language” [19].

In a health care setting, this usually occurs when a spoken language interpreter is handed a document in the moment during the interpreting assignment. Documents can have varying lengths, and there is often no opportunity for the interpreter to review them before the interpreting encounter. Although this process can be effective for documents that are short and clear, interpreters are sometimes asked to provide a sight translation for longer and more complex documents. These longer documents include such important items as consent forms, forms for advance directives, and detailed educational materials. Such forms should be translated prior to their use.

The challenges associated with sight translation include requiring the interpreter to speak and read in two languages at the same time. Ultimately, this may threaten the accuracy, clarity, and thoroughness of communication for the patient and the health care provider.

Why Skilled Interpreters are Key to Effective Health Care

It is important to point out that—while all interpreters, by definition, are bilingual—not every bilingual person can interpret. Professional interpreters undertake substantial training in both languages and in moving between them. These days, many interpreters have master’s degrees, reflecting the years of practice necessary to become proficient at rendering the product of one language into another in an efficient, accurate, and meaningful way. In addition, for a limited number of languages, national certification programs are in place. However, certification is not available for all spoken languages.

Bilingual ability differs from person to person. Most bilingual individuals have differential levels of competence in their two languages, often more so if they have not formally studied both languages and learned how to translate and interpret in each of the two languages. This requires more skill than being conversationally fluent in two languages.

While it is convenient and not uncommon to use family members, friends, or passersby as interpreters, the appropriateness of this practice diminishes as the stakes of the event become greater. Whereas a person’s sister might function well in assisting in the communication between persons at an informal dinner, the same sister may be seriously unqualified to function as an interpreter in a health care setting. The fact that a patient might feel more comfortable with a family member should not outweigh the need for an accurate interpretation of what the health care professional says and how the patient responds.

Moreover, untrained interpreters may balk at explanations involving bodily functions or critical injuries. Due to cultural beliefs or an age difference between a younger family member and an elder, it might be considered disrespectful for a younger person to present many types of questions to an elder. This is especially true when dealing with personal or sensitive topics.

In addition, legal issues related to privacy come into play when employing an interpreter in a health care setting. Professional health care interpreters will have learned how to discuss these issues in their training.

Finally, it may not be sufficient to have a good interpreter. In many settings, especially those involving very specialized vocabulary (such as clinical settings and research environments), interpreters may need to have special experience with fields of health care, the vocabulary used in those fields, and the indications that are under discussion.

Although appropriate and in-person interpreters may not always be readily available, the authors of this manuscript believe they are necessary for effective communication with individuals who speak a different language from their health care provider. Providers may feel that the absence of an interpreter is equivalent to the absence of effective communication, and the patient, without an interpreter, is not participating in their own health care. No one is served in this situation.

To demonstrate the high stakes of such a situation, Fadiman’s classic study of cross-cultural communication in medical settings, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures, provides an extended description of interactions involving a Hmong child over many years [12].

Interpretation Challenges and Signed Languages

Signed language interpreting and spoken language interpreting have almost everything in common except the channel of the signals. Signed languages, such as American Sign Language, can fully discuss any medical or scientific topic that can be discussed in English or another spoken language.

The primary differences in interpreting between a signed and a spoken language and interpreting between two spoken languages tend to be practical differences. Interpreting an English utterance into a signed language may take a bit more time than the equivalent spoken language interpretation, especially if there is a lot of technical vocabulary. Technical words may have to be spelled out if there is not a sign in the language corresponding to that concept.

In addition, when two spoken languages are involved, it is easy for the health care practitioner to notice when the interpreter’s turn at speaking is finished. It is not always so easy for a hearing person with little experience in such situations to know when the interpreter is finished with their utterance if they are interpreting spoken utterances into sign language.

With a sign language interpreter, there may be a substantial delay between when the practitioner is finished speaking and when the interpreter finishes interpreting the utterance. This can lead to overlaps that hinder the quality of the communication. A certain amount of flexibility and patience may be required of the medical practitioner in order not to overlap excessively with the interpreter.

Lastly, as a clinical event involving an interpreter will almost certainly require more time than one in which the patient shares a language with the practitioner, it is advisable that practitioners adopt flexible scheduling practices to accommodate patients who require interpreters.

Earlier in this discussion, the authors of this manuscript noted the immediacy of the process in which an interpreter takes a piece of speech or sign and renders it—simultaneously or consecutively—into another language without the opportunity to consider alternative renderings. This focus applies to formal interpretation between two differing languages, but differences within the same language regarding health literacy terms should also be considered. The patient and the health professional may both speak English or Spanish or Urdu, but their comprehension may not be equivalent. The specialized medical terminology and complex concepts for describing disease or treatment processes often hamper understanding.

Further, in an interpreted consultation, there are two potential sources of misunderstanding. An interpreter may misunderstand (and misinterpret) the patient, and the doctor (or the patient) may misunderstand the interpreter. Teach-back is a very effective method for identifying trouble spots in interpretation.

Cultural Appropriateness of the Interpreter

Because interpreters are the “voice” of the person for whom they are interpreting, more should be considered than just the technical message to be transmitted. A patient in a medical encounter wants the best, most accurate representation. In general, it is considered appropriate for the cultural and ethnic characteristics of the interpreter to match those of the patient.

Overall, it is important that the individual’s voice, whether spoken or signed, be presented clearly and accurately by a qualified interpreter, especially in clinical and hospital settings, where information must be transmitted accurately and completely.

When scheduling an interpreter, those charged with hiring should consider the nature of the visit and its content. Sharing this information in advance provides the spoken or sign language interpreter the opportunity to prepare. Preparation includes such activities as identifying terms that might not exist in both languages. In addition, recruiters should consider ethnic and gender characteristics, especially when the gender of the interpreter is relevant to the health care visit, such as in reproductive health care for either men or women, or other issues that the individual perceives as intimate, e.g., physical or psychological trauma.

Of course, considering all these factors is not always practical, and at times, the match will not be perfect. For example, because proportionally there are more women in the field of interpreting than there are men, it is not uncommon for a male client to have a female interpreter.

Gesture and Miscommunication

Gestures are movements of the hands, arms, head, and other parts of the body that convey meaning and/or serve interactive functions. Research has focused on spontaneous gestures that co-occur with speech and are beneath the level of conscious recall [17]. Unlike conventionalized gestures, spontaneous gestures do not have prescribed, predictable forms, yet they reveal aspects of thought that are not verbalized.

One finding of gesture research especially relevant for clinician-patient interaction, with potentially the biggest impact on patient health, is back-channeling. “Back-channeling” refers to the recipient’s signals of attention to the conversation. Often, they are verbal and overlap with the doctor’s speech, including utterances such as “uh-huh,” “oh, really,” and similar listening cues.

Equally common gestures, however, include head nods in American and many other cultures [23]. The rate of nodding varies across cultures, and some countries, such as Bulgaria, use lateral shakes (akin to the American head movement for negation) as back channels instead. Cultures use whichever head movement (if any) is associated with affirmation to back-channel.

If the patient is back-channeling using nods associated with affirmation, it can be very tempting for overworked health care personnel to ignore vacant expressions in a patient’s eyes and facial expressions of confusion. Such nods, however, do not signal understanding—they signal only attentive listening.

Research has shown that speakers often request listener back channels by nodding while they themselves are speaking [16]. Listeners often respond with their own nods almost immediately if the speaker is nodding as well. Such back-channel requests are beneath the level of conscious recall, so health care professionals may unwittingly be triggering back-channeling in patients, which is then misinterpreted as understanding or assent. This challenge works both ways.

Additional Challenges for Interpreters

The authors have identified many what might be called traditional or technical challenges for interpreters working in medical settings, but much needs to be learned about the full range of interpersonal challenges for these professionals. In a 2016 qualitative study of the experiences of interpreters who supported the transition from oncology to palliative care, researchers identified the study aims:

Medical consultations focused on managing the transition to palliative care are interpersonally challenging and require high levels of communicative competence. In the context of non-English speaking patients, communication challenges are further complicated due to the requirement of interpreting; a process with the potential to add intense layers of complexity in the clinical encounter, such as misunderstanding, misrepresentation and power imbalances [15].

The sensitivity of this specific example seems to be a likely proxy for all such emotional and complicated interactions. The investigators conclude:

The results suggest that interpreters face a range of often concealed interpersonal and interprofessional challenges and recognition of such dynamics will help provide necessary support for these key stakeholders in the transition

to palliative care. Enriched understanding of interpreters’ experiences has clinical implications on improving how health professionals interact and work with interpreters in this sensitive setting [15].

The authors of this perspective urge attention to the needs of the interpreter in addition to the needs of the patient and the medical team.

Interpreters and Translators in Health Care

It is possible to approach the problems related to interpreting and translating more comprehensively and systematically, but doing so requires strategy, organizational commitment, planning, training, and budget. Two examples of such comprehensive and systematic approaches are those provided by Language Line Solutions and the Health Care Interpreter Network (HCIN).

Language Line Solutions, originally known as Communication and Language Line (CALL) was founded in 1982 in San Jose, California to help police communicate with some 65,000 Vietnamese refugees in the area. Language Line provides interpretation and translation services for law enforcement, health care organizations, legal courts, schools, and businesses.

HCIN was originated by Contra Costa Health Services in California. HCIN is focused on medical interpreting and offers an instantly accessible interpreting network and cost-effective videophone medical interpreting in 38 spoken languages and in American Sign Language. HCIN provides by-appointment video or phone health care interpreting in approximately 60 additional languages.

Both organizations provide continuing education for professional interpreters through online platforms. For example, HCIN Learn offers a three-hour course covering interpreting for prenatal genetic counseling that is described as covering concepts in human genetics, the work of counselors who advise about prenatal genetics and, specifically, guidance on the challenges in interpreting that arise in this setting. The course also provides technical language and practice elements for interpreters.

In the introduction to a manuscript examining HCIN, Jacobs et al. argue that “providing health care in a language that the patient can understand is a moral imperative. Allowing patients with limited English proficiency to receive sub-standard care and consequently be at risk for disparities in care, health, and well-being is unacceptable, especially in light of the breadth of linguistic access services available, even in remote areas” [14]. HCIN has been successfully adopted by Contra Costa Health Services, and is now utilized in 50 health clinics and hospitals throughout the system.

Translation, Interpretation, and Quality Improvement

Quality improvement in all programs dealing with patients and medical staff across languages constitutes an important element of understanding the full impact of language access and services. One model for discussion of the quality of services is based on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s six quality domains of safety, timeliness, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and patient-centeredness [18]. Each of these domains can pertain directly to opportunities to improve the quality of translation and interpretation in medical settings.

As an example of how quality improvement in interpretation can be implemented is provided in a modular resource from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The free and multifaceted TeamSTEPPS Limited English Proficiency module trains health care teams to work with interpreters [2]. It also prompts interpreters to speak up if they discern a safety issue. As the site notes, citing Divi and colleagues, “Recent research suggests that adverse events that affect limited-English-proficient (LEP) patients are more frequently caused by communication problems and are more likely to result in serious harm compared to English-speaking patients” [11].

Teach Back and Interpretation

In Sudore and Schillinger’s article on interventions to improve care for patients with limited health literacy, they operationalize the teach-back method [21], which can also be used to ensure quality during interpretation sessions: “The teach back method is a technique in which the clinician asks patients to restate or demonstrate the knowledge or technique just taught” [21]. A patient-centered strategy includes assessing how well the patient understands the information the physician provides, using a methodical and sensitive approach that requires the medical professional to be alert to the needs of the patient. Important elements of the teach back method include (a) confirmation of understanding, (b) reinforcement, and (c) numeracy and presenting risk information.

The authors note that asking “Do you have any questions?” or “Do you understand?” does not confirm understanding. Instead, the authors recommend asking “What questions do you have?” In an earlier work, Schillinger and colleagues also recommend that the physician destigmatize interactions by putting the responsibility back on themselves, stating, for example, “I’ve just said a lot of things. To make sure I did a good job and explained things clearly, can you describe to me . . . ?” [20]. In that same study, Schillinger notes that the method “does not result in longer visits and has been associated with diabetic patients having better metabolic control” [20]. These techniques also allow the provider to emphasize important health information, conveyed via the interpreter, in a culturally sensitive manner.

Universal Precautions and Health Literacy

The second edition of the AHRQ’s “Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit” describes health literacy universal precautions as “the steps that practices take when they assume that all patients may have difficulty comprehending health information and accessing health services” [4]. The precautions include the following elements: (a) simplifying communication with and confirming comprehension for all patients to minimize the risk of miscommunication, (b) making the office environment and health care system easier to navigate, and (c) supporting patients’ efforts to improve their health.

AHRQ also provides its rationale for this approach:

Experts recommend assuming that everyone may have difficulty understanding and creating an environment where all patients can thrive. Only 12 percent of U.S. adults have the health literacy skills needed to manage the demands of our complex health care system, and even these individuals’ ability to absorb and use health information can be compromised by stress or illness. Like with blood safety, universal precautions should be taken to address health literacy because we can’t know which patients are challenged by health care information and tasks at any given time. It is important to bring this same principle of assuming the likelihood of difficulties in comprehension into any interpretation between language settings. This will help lessen the risk of miscommunication. [4]

Not all medical interactions are in hospitals or offices. In a discussion of patient communication in palliative care and hospice settings, Alves and Meier note: “Doctors practice as we are trained” [6].

The competing and stressful pressures on clinicians are complicated by a myriad of elements, outlined in Brigham and colleagues’ National Academies article “A Journey to Construct an All-Encompassing Conceptual Model of Factors Affecting Clinician Well-Being and Resilience” [7]. This important effort to have a holistic view of the provider might well be matched with a similar model for the patient and for the interpreter. The conceptual model presented in the Brigham paper, which considers clinicians, patients, families and caregivers, and all of the aspects that influence all of their behaviors, provides an important starting place for the effort to provide a holistic view of the provider and the health care system.

Measuring Patient Experiences with Interpreter Services

Since 1995, AHRQ has offered the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) to advance scientific understanding of the patient’s experience with health care [3]. AHRQ has developed a series of resources to be used in medical settings, including specific, freely-available supplemental surveys that assess patient and provider experiences with interpreter services in medical settings [1]. AHRQ data are a rich resource for internal analysis and shared data comparisons. Among other items, patients are asked about their needs for services, the services provided, the timeliness of the services, and the quality of the interpreter. Sample survey questions include

- “How often did this interpreter treat you with courtesy and respect?”

- “Using any number from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst interpreter possible and 10 is the best interpreter possible, what number would you use to rate this interpreter?”

- “How often did you use a friend or family member as an interpreter when you talked with this provider?”

- “Did you use a child younger than 18 to help you talk with this provider?”

Different CAHPS surveys use slightly different questions about interpreter services [5]. For example, Hospital CAHPS includes the question, “During this hospital stay, did hospital staff tell you that you had a right to interpreter services free of charge?”

Pitfalls of Electronic Interpretation as a Solution

The introduction of handheld, speech-driven electronic interpretation devices seems, at first, to address many of the problems that arise when providers and patients do not speak the same language. However, these devices lack the precision and flexibility required for medical interactions. Devices render words that sound alike such as “oral” and “aural)” or “optic” and the suffix “otic”), but have, often critically differing meanings. Words that are said out of context, or words that are unfamiliar can stymie effective rendering of communication. Devices aren’t able to differentiate or understand any miscommunication in the range of meanings of a word such as “PAP,” which can vary from “the common gynecological test of a PAP smear,” to “positive airway pressure,” to “a synonym for soft or baby food” lacking the cues for context. Such a device could also have difficulty relaying like-sounding words such as dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) and dysphasia (a brain injury that complicates communication or makes it impossible). Machines are improving, but they are not the solution in many medical settings.

Looking Forward

Having reviewed the many challenges related to language, interpretation, and translation in health care settings, the authors of this manuscript believe that improving communication via interpretation and/or translation between clinicians and patients depends on (a) strategic preparation; (b) careful and consistent implementation of rules; and, as with any significant effort, (c) commitment to improvement through experience.

Much research is needed regarding the intersections of language, interpretation, translation, and health literacy. Immediate research needs include comparisons across varying methods of interpretation and translation services and the effectiveness of specific methods and tools. The impact of nonverbal cues and gestures in medical settings need greater attention. There is also a need for better understanding of how to bring individuals from differing cultural perspectives into the processes that directly affect them.

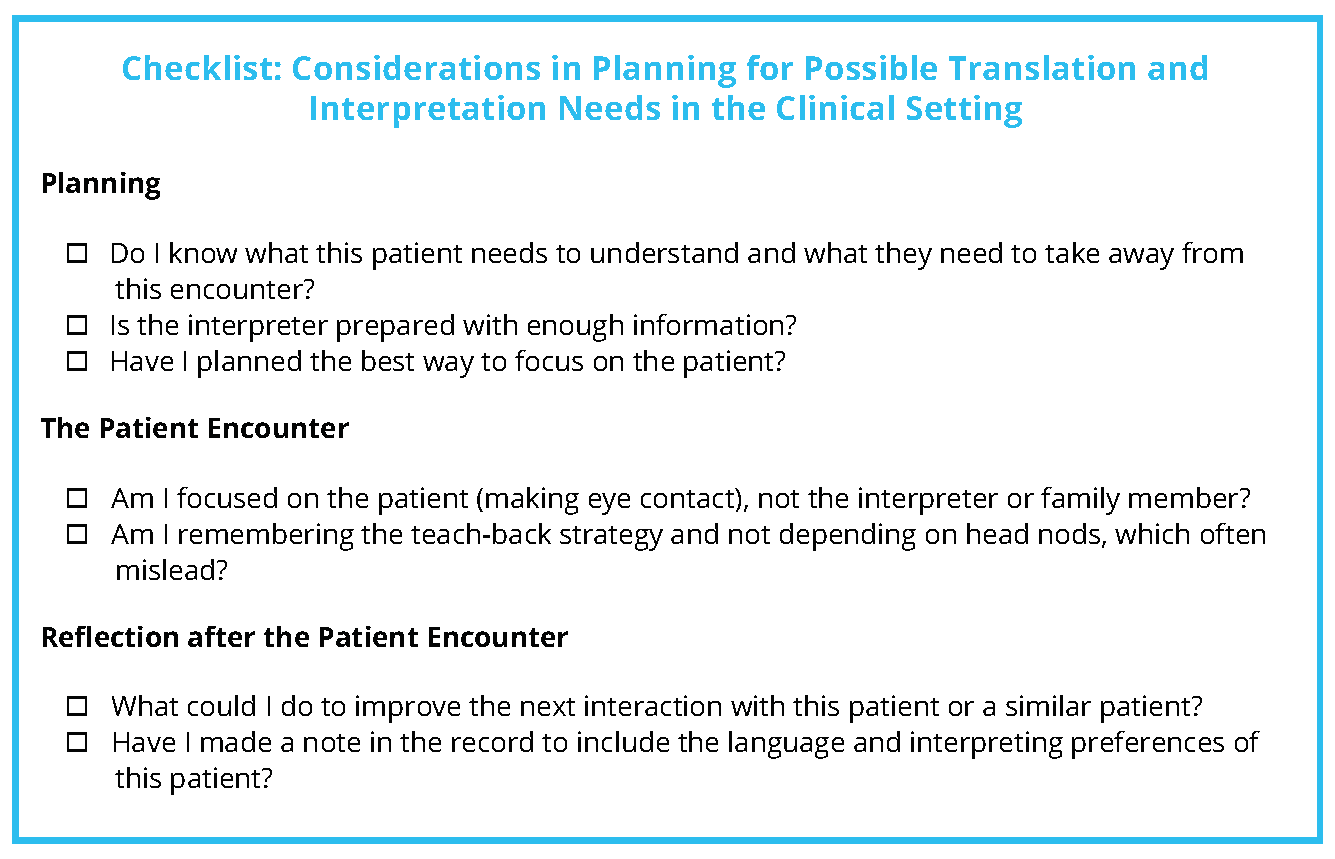

The authors of this manuscript offer below a few suggestions for developing habits that health care providers may find helpful. The suggestions are followed by a short checklist (on the following page) that can be used in the clinical setting.

Planning Ahead: Clinical Setting

If possible, prior to a first encounter with a patient who communicates in a different language than yours, consider: how might my staff and I determine what language preferences and accommodations are needed for effective communication with the individual?

This is also a good time to think about what materials might be provided and how they will be used.

Additional questions to ask yourself and your team are: How will I manage the time in the appointment? Do I have a good resource for evaluating the credentials of any interpreters? Are there going to be any special needs for the interpreter, such as a gown or a mask? Has the interpreter been prepared for the interaction to make the most effective use of their skills? (E.g., the following introduction for an interpreter: “Today, the patient is going to be told he is going to undergo chemotherapy. This fact sheet will be used by a patient who speaks Portuguese, and I will be explaining how the medication works and what to expect.”)

Remember, each time, to look at the individual (your attention is important), not the interpreter.

During the Patient Encounter: Clinical Setting

Focus on the patient. Looking the patient in the eye will help in judging their level of understanding. Ensure that you are talking to the individual, not the interpreter or a family member. This will help ensure that the patient makes their own decisions in the encounter.

Ask yourself: Will embarrassment about topics, culture, age, or the presence of family members in the room keep my patient from telling me the truth? Have I used the teach-back method to confirm my patient understands me? (E.g., “Please, tell me what I’ve asked you to do? How will you take this medication? When do you need to be rechecked?”)

After the Patient Encounter: Clinical Setting

Ask yourself: How did it go? Are there any adjustments I need to make for the next interaction with this patient or any other individual who speaks a different language? Are there any adjustments I need to make in working with an interpreter, either in person or by teleconference?

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! As the US becomes more diverse, language and translation are becoming increasingly critical parts of practicing medicine. The authors of this #NAMPerspectives urge clinicians to consider these issues before they are sitting with from a patient: https://doi.org/10.31478/202002c

Tweet this! As the US becomes more diverse, language and translation are becoming increasingly critical parts of practicing medicine. The authors of this #NAMPerspectives urge clinicians to consider these issues before they are sitting with from a patient: https://doi.org/10.31478/202002c

![]() Tweet this! Authors of a #NAMPerspectives discussion paper make clear that “while all interpreters, by definition, are bilingual, not every bilingual person can interpret” in a call for skilled interpreters to be embedded in clinician-patient conversations: https://doi.org/10.31478/202002c

Tweet this! Authors of a #NAMPerspectives discussion paper make clear that “while all interpreters, by definition, are bilingual, not every bilingual person can interpret” in a call for skilled interpreters to be embedded in clinician-patient conversations: https://doi.org/10.31478/202002c

![]() Tweet this! Electronic interpretation devices seem to address many interpretation problems, but they currently lack the precision and flexibility required for medical interactions. Read about more challenges and potential solutions: https://doi.org/10.31478/202002c #NAMPerspectives

Tweet this! Electronic interpretation devices seem to address many interpretation problems, but they currently lack the precision and flexibility required for medical interactions. Read about more challenges and potential solutions: https://doi.org/10.31478/202002c #NAMPerspectives

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). 2017. Supplemental items for the CAHPS hospital survey: Interpreter services. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/item-sets/literacy/suppl-interpreter-service-items.html (accessed January 14, 2020).

- AHRQ. 2017. TeamSTEPPS limited English proficiency module. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/lep/index.html (accessed May 9, 2019).

- AHRQ. 2018. CAHPS hospital survey. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/hospital/index.html (accessed May 9, 2019).

- AHRQ. 2019. AHRQ health literacy universal precautions toolkit. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/quality-resources/tools/literacytoolkit/index.html (accessed January 14, 2020).

- AHRQ. 2019. CAHPS surveys and guidance: What are CAHPS surveys? Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/index.html (accessed May 8, 2019).

- Alves, B. and D. Meier. 2015. Health Literacy and Palliative Care: What Really Happens to Patients. NAM Perspectives. Commentary, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201512c

- Brigham, T., C. Barden, A. L. Dopp, A. Hengerer, J. Kaplan, B. Malone, C. Martin, M. McHugh, and L. M. Nora. 2018. A Journey to Construct an All-Encompassing Conceptual Model of Factors Affecting Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201801b

- Burgess, A. 1984. Is translation possible? Translation: The Journal of Literary Translation XII:3–7.

- Burke, K. 1966. Language as symbolic action; essays on life, literature, and method. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Carroll-Johnson, R. M. 2006. Lost in translation. Oncology Nursing Forum 33(5):853. https://doi.org/10.1188/06.ONF.853

- Divi, C., R. G. Koss, S. P. Schmaltz, and J. M. Loeb. 2007. Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: A pilot study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19(2):60-67. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzl069

- Fadiman, A. 1997. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures. 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

- Flores, G. 2006. Language barriers to health care in the united states. New England Journal of Medicine 355(3):229-231.

- Jacobs, E. A., G. S. Leos, P. J. Rathouz, and P. Fu, Jr. 2011. Shared networks of interpreter services, at relatively low cost, can help providers serve patients with limited English skills. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30(10):1930-1938. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff .2011.0667

- Kirby, E., A. Broom, P. Good, V. Bowden, and Z. Lwin. 2017. Experiences of interpreters in supporting the transition from oncology to palliative care: A qualitative study. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 13(5):e497-e505. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.12563

- McClave, E. Z. 2000. Linguistic functions of head movements in the context of speech. Journal of Pragmatics 32(7):855-878. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00079-X

- McNeill, D. 2005. Gesture and thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Institute of Medicine. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027.

- National Council on Interpreting in Health Care. 2005. National standards of practice for interpreters in health care. Available at: https://www.ncihc.org/assets/documents/publications/NCIHC%20National%20Standards%20of%20Practice.pdf (accessed May 13, 2019).

- Schillinger, D., J. Piette, K. Grumbach, F. Wang, C. Wilson, C. Daher, K. Leong-Grotz, C. Castro, and A. B. Bindman. 2003. Closing the loop: Physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Archives of Internal Medicine 163(1):83-90.

- Sudore, R. L., and D. Schillinger. 2009. Interventions to improve care for patients with limited health literacy. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management 16(1):20-29.

- US Census Bureau. 2015. Census bureau reports at least 350 languages spoken in U.S. Homes. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/pressreleases/2015/cb15-185.html (accessed May 10, 2019).

- Yngve, V. H. 1970. On getting a word in edgewise. 1970, Chicago.

- Youdelman, M. 2009. What’s in a word? A guide to understanding interpreting and translation in health care. Available at: https://9kqpw4dcaw91s37kozm5jx17-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Whats-in-a-Word-FINAL.pdf (accessed May 13, 2019).

- Jacobs, B., A. M. Ryan, K. S. Henrichs, and B. D. Weiss. 2018. Medical Interpreters in Outpatient Practice. Annals of Family Medicine 16(1): 70-76. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2154

- Ku, L. and G. Flores. 2005. Pay now or pay later: Providing interpreter services in health care. Health Affairs (Millwood) 24(2): 435-444. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.435

- Harsham, P. 1984. A misinterpreted word worth $71 million. Medical Economics June: 289-292.