Jump to

- Structure of the Indian Music Industry

- 1. Live Industry

- 2. Recording Industry

- 3. Publishing Industry

- Indian Music Industry Stats: India's Digital Revolution By the Numbers

- Indian Music Industry Analysis: Prospects and Challenges of the Streaming Market

- Continuous Growth of Addressable Streaming Market

- Streaming Alternatives

- Pirate Services

- The problem of Monetization.

- Local Streaming Services vs. International Heavyweights

- Bollywood and Film Music

- Bollywood vs. Regional Music

- The Sound of Indian Film

- Role of Soundtrack and the Place of Non-film Music

- Live Performance and Brand Sponsorships

- Opportunities for International Music

We want to thank Aniket Rajgarhia and Roochay Shukla of the China & India music services company Outdustry for landing their insider's expertise into the Indian market and helping us with the research.

Also, If you want to explore the opportunities of the Indian music market, check out this list of local music companies, — from prominent festival promoters and booking agencies to record labels and live venues — curated by industry insiders for international music community

The Indian market is one of the hottest topics in the industry right now. The news of Spotify and Youtube Music entering the local market, the price war that followed — as we already mentioned, India will probably become the main battleground of the global streaming industry in the years to come. The local market will attract more and more interest in the future, so here we go. Here’s everything you need to know about the Indian music market.

Structure of the Indian Music Industry

With its primarily young, rapidly growing population — currently at 1.3 billion — many music professionals are now looking to India as the music industry’s next great frontier. The revenues of the Indian music industry are on a rapid rise for the last few years — primarily driven by the country's growing online population. However, India’s massive film industry still plays an outsized role in the music business — with 80% of the country’s music revenue reportedly generated by soundtracks for Bollywood films. That is for various reasons, which we'll explore down the road — but for now let’s start with a couple of quick statistics to underline the structure of the market and get everyone on the same page. First, we need to review the revenue of the industry, split between 3 main core business: recording, live and publishing.

1. Live Industry

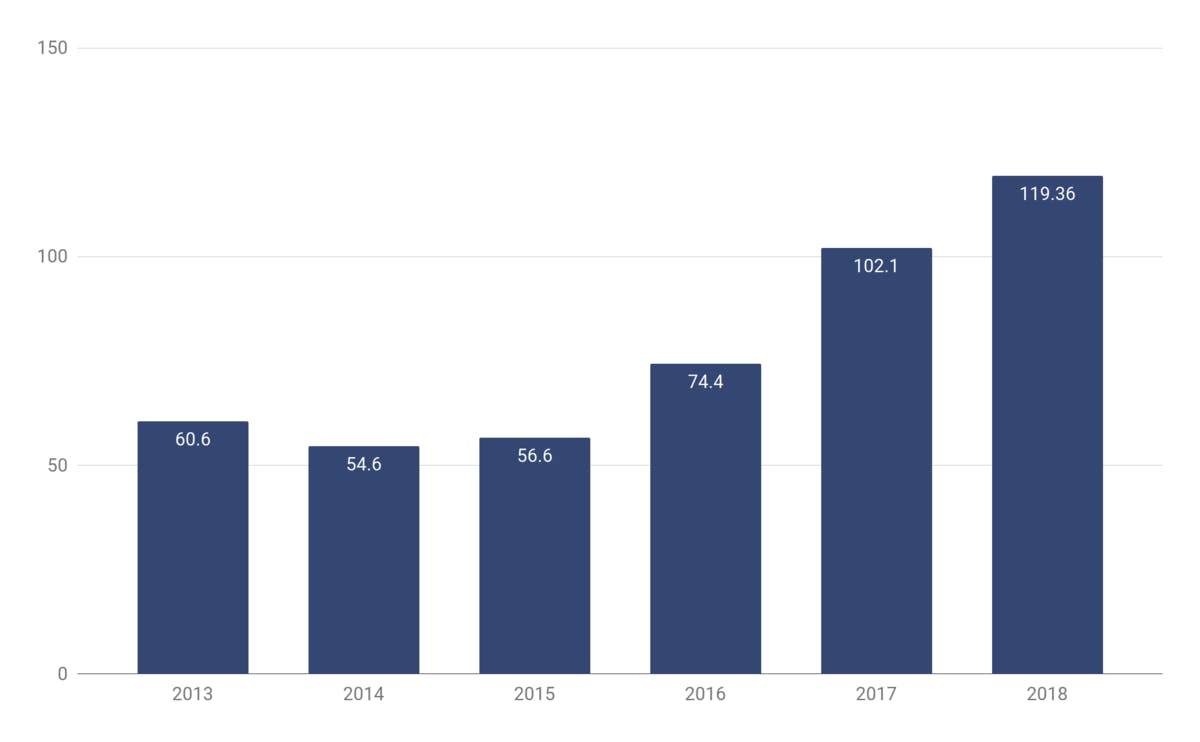

As usual, the estimation of live revenues is by far the trickiest part of sizing the industry. Due to the fragmented nature of the live business, comprehensive, accurate quotes are hard to come by.

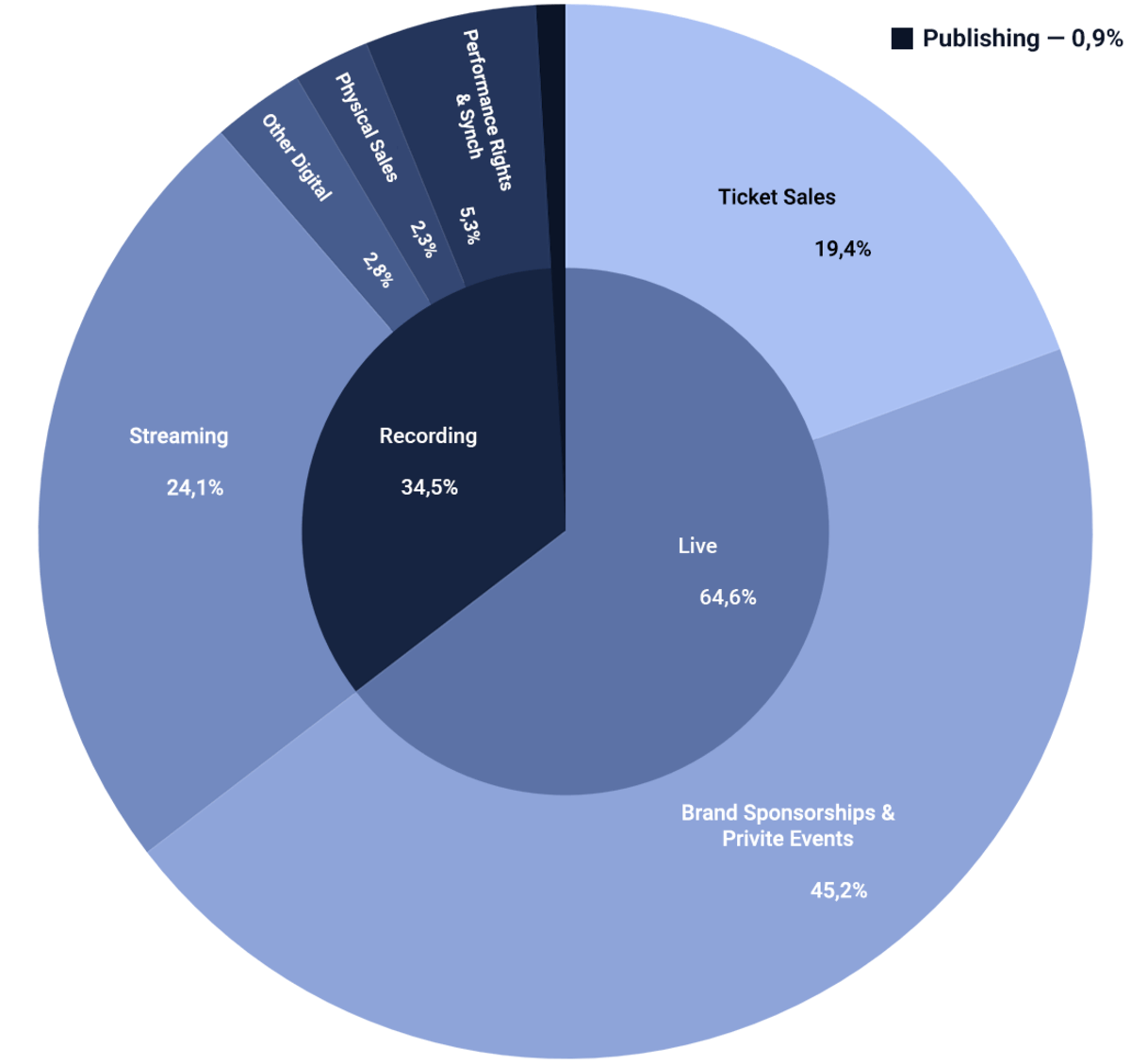

- Drawing on the information disclosed throughout the Indian Music Convention, PwC data, and industry discussions the total revenues of live business can be put at around $280 million

- In line with PwC estimations, ticket sales accounted for 30% of all live revenues, while the rest is split up between brand sponsorships, private events, merch sales, and so forth.

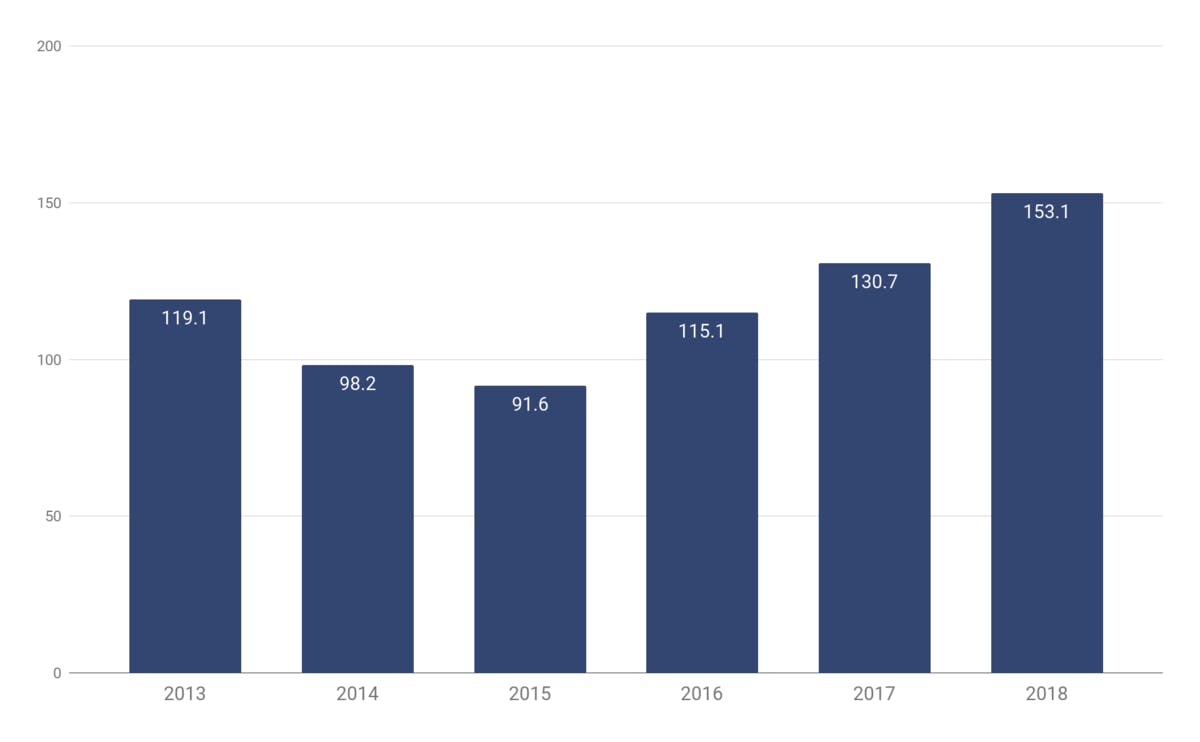

2. Recording Industry

3. Publishing Industry

- The publishing in India is still in its cradle: up until 2012, the Music Copyright Act of India assigned copyrights to film producers instead of the actual songwriters.

- Although the necessary amendments have been made, the publishing pipeline is still extremely underdeveloped, and most of the artists don’t earn any royalties

- Royalties to songwriters and composers made up less than 1% of the total industry’s revenue, or $4 million

Summing up the revenues across the three main sub-industries, we estimate the scope of the Indian music market at $443 million.

Indian Music Industry Revenue by Source, 2018

Sources: IFPI, PwC, VISION 2022, IPRS

With the country positioned 15th in the 2018 IFPI rankings, local music professionals are aiming to break the market into the top 10 by 2022. That means that the industry will have not only to keep up its current growth but accelerate continuously in the coming years. However, what will drive this expansion?

Indian Music Industry Stats: India's Digital Revolution By the Numbers

In 2018, India became the 5th biggest economy in the world in terms of the current GDP. It’s the fastest-growing economy out of the top-10, projected 7% CAGR up until 2023. This almost unprecedented economic growth is powered by the population of 1,35 billion people, which keeps on rising — India is expected to overtake China in total residents and become the world’s most populated country by 2027. At the same time, that population is extremely young: according to the 2011 census, more than 52% of India’s population was under 25 y.o.

Near-record economic growth, young population (and we all know what’s music industry’s primary demographic) — that’s all good news for the Indian music professionals. However, there is a single trend in India that means more to the music business than anything else — the country’s rapid digitalization.

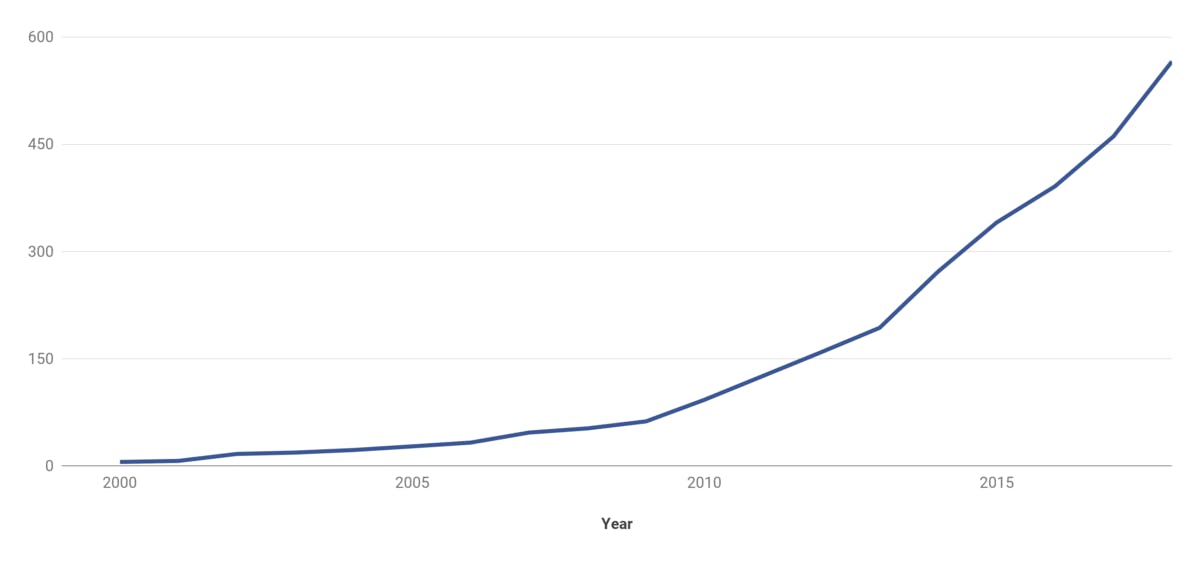

Back in 2016, a new 4G telecom service Reliance Jio has entered the Indian market. Its mission statement was to “provide broadband for every Indian”, mirroring the Digital India initiative, launched by the government earlier the same year. To achieve that, Jio hit the market with an extremely aggressive strategy, starting a price war amongst the local telecom providers.

Just two years later, in 2018, India became the country with the cheapest mobile internet in the world. According to Cable, 1 GB of mobile data in India now costs just $0,26 — for comparison, the average in the US is 47,5 times greater at $12,37/GB. In three years, from 2015 to 2018, the country’s internet population grew more than 60% to 566 million.

Internet users in India, 2000-2018, Million people

Source: The World Bank, ICUBE

Indian Music Industry Analysis: Prospects and Challenges of the Streaming Market

The surge of internet usage created a fertile ground for the streaming services on the Indian market. The two historical players, Gaana and Saavn (known as JioSaavn since the 2018 merger) introduced their offers to the market on the verge of the 2010s — but the first explosion in terms of streaming user-base followed around 2015-2016.

The digital revenues (that were mostly stagnant up to that point) grew 210% from 2015 to 2018. Local streaming services has broken into the mainstream and launched the transition to the new music distribution model. Reportedly, as of December 2018 streaming services counted 150 million users in India. However, that might be just the beginning.

According to company statements, Gaana and JioSaavn, have each amassed 100 million users by April 2019. Furthermore, industry insiders anticipate the streaming user-base to hit 500 million in the next couple of years — and they might not be that far from the truth.

Continuous Growth of Addressable Streaming Market

First of all, while the telecom revolution has opened the door for the online economy, the process of internet adoption is far from over. Current "566 million internet users" still represent just south of 40% of the country’s total population — while penetration rates across developed markets average at around 80%.

With the telecom infrastructure reaching the most remote parts of the country, cheap data plans and governmental support, there’s no reason for the current digitalization trend to slow down. And if it persists India will reach the ≈80% penetration figures quite quickly. That would mean that in the next few years the addressable audience of streaming will double to 1,100 million, potentially creating the single biggest streaming audience in the world.

Streaming Alternatives

According to Nielsen, 94% of the online consumers in India listen to music — and 71% of them say that music is an important (or very important) part of their lives. If that’s the case, however, why the music streaming user base made up only 26% of the country’s online population back in 2018? The point is that streaming services are just one of the consumption channels available to the Indian consumer — and not necessarily the most attractive one.

The most prominent audio streaming alternative is YouTube. Video-streaming heavyweight has become a massive part of the country’s entertainment landscape. Reportedly, YouTube reaches over 80% of the online users in India, and 245 million Indians are accessing the service every month.

The reason behind the platform’s success as a music consumption channel is the significance of video-synced music content in the country. Shaped by a century-long tradition of film music, Indian consumers are used to consuming audio synched to video content and built into the bigger cinematic narrative. At this point, you probably heard of T-Series — Indian record label/film production company and the owner of the most-subscribed YouTube channel in the world.

YouTube is free, visual, and easily accessible. However, it can’t wholly substitute streaming services, since music is an off-screen, on-the-go content — and video-platforms are not cut out for that.

Pirate Services

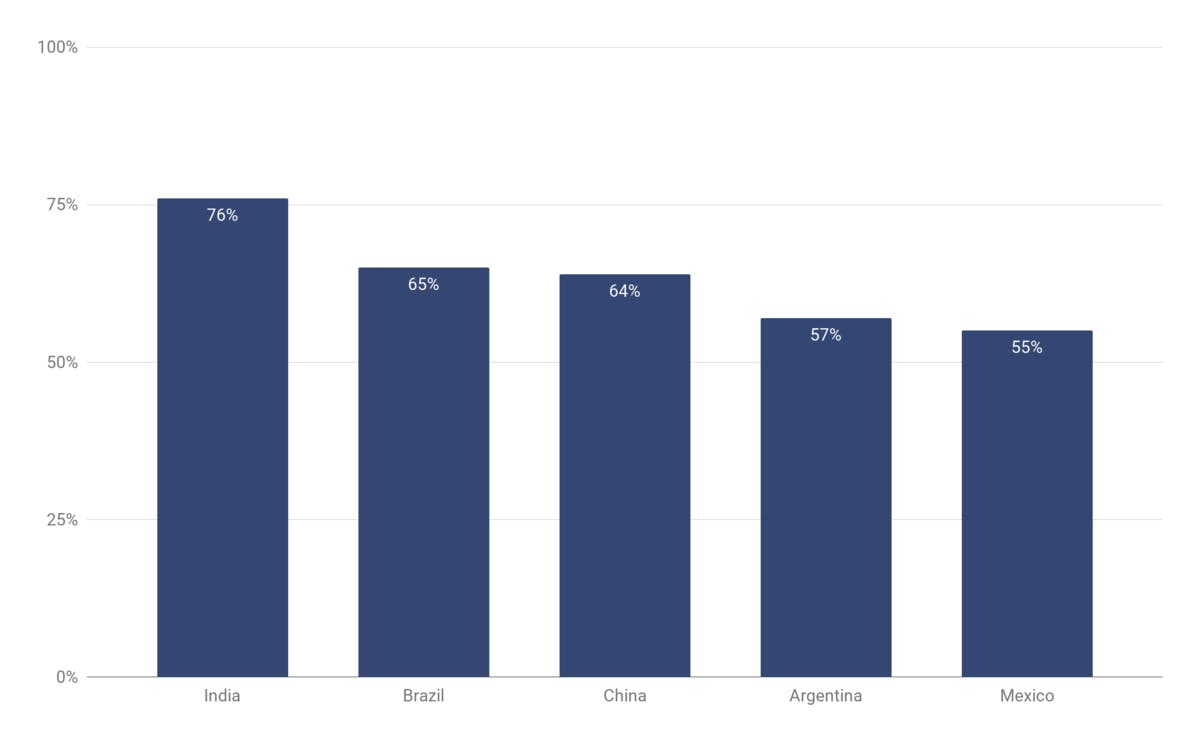

When it comes to off-screen consumption, the biggest streaming alternative is pirate services. Currently, India is the first country in the world in terms of piracy rates. According to the latest surveys, 76% of internet users admit to using pirate services in the last three months — and by far the most popular unlicensed channel are the stream-ripping websites, allowing their users to turn the YouTube links into mp3 files. Then, the mp3 files can be easily “sideloaded” onto the Android-operated devices (which account for over 90% of all smartphones in India) through external SD-cards.

% of internet users, who’ve accessed the pirate services at least once in the last three month, by country, 2018

Source: Digital Music Study 2018

Depending on the source, estimated losses of the recording business linked to piracy range from $130 to $260 million. The impact of piracy is notoriously hard to measure, but even by the most modest estimations, 80% of all recording revenues are lost to the pirates. Unlicensed consumption is undoubtedly one of the main roadblocks on the path to the streaming ecosystem in India.

However, there’s a positive angle to the piracy problem: in the long-run, the legal alternatives are bound to take over. Piracy is still a huge problem today — but it’s nowhere near what it was five years ago, when, reportedly, 98% of all digital music consumption was unlicensed. With the governmental support and marketing budgets of all streaming services that are already on the market, illegal consumption is bound to turn into the ad-supported licensed listening, giving yet another push to the recording revenues.

In that sense, the current situation on the Indian market is reminiscent of the piracy-heavy pre-2015 China — and transition to the licensed streaming music turned the Chinese market into the fastest growing music industry in the world.

To sum up, the Indian market is well-positioned to grow the streaming user-base streaming user base in the coming years. However, as the Chinese market taught us, music piracy has yet another long-term negative effect — it institutes the idea that music should be free, creating a huge obstacle for the development of a subscription-based music economy.

The problem of Monetization.

Sure, “pirates” will eventually convert to ad-supported streaming users — but turning them into paying customers is a massive challenge for the local industry. Another factor that plays into that situation is the price-sensitivity of the Indian consumer in general. Consumers in India are dubbed value-conscious — always keeping in mind the value/price proposition. However, if the music was free for the past ten years, why should you pay for it?

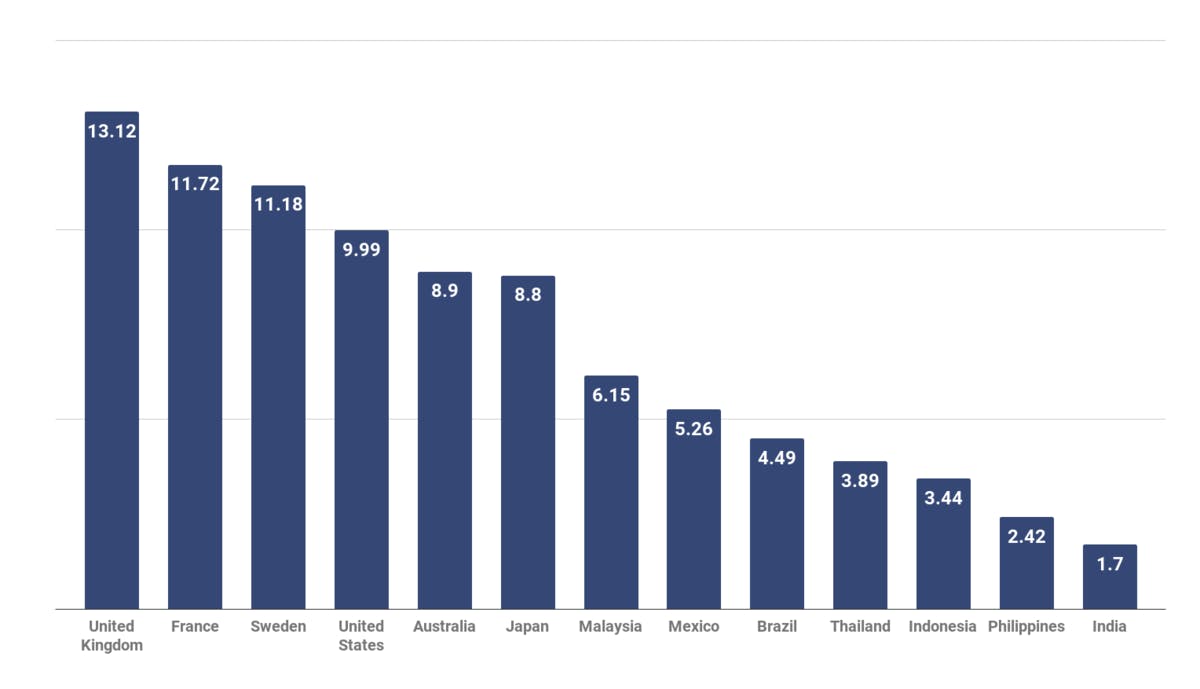

The prominence of video-content, the popularity of YouTube, the history of rampant piracy – all those factors make a conversion to paid streaming extremely problematic, even though the subscriptions are priced extremely cheap. For example, Apple Music in India is now priced at just $1,43/month, with student subscriptions available at a mere $0.71.

Spotify Premium Price in Selected Markets, $US

Source:Music Business Worldwide

However, even with the prices slashed down, conversion remains dismal. To draw parallels with China once again, the average subscription rate there is thought to be record-low at just 3%. Well, if we look over at India, only 1% of all streaming users pay for premium subscriptions directly.

That poses a huge problem for the industry. In line with the freemium model, ad-supported consumption is supposed to be more of a promotion for the premium service. Any sustainable ecosystem has to rely on the premium subscriptions — or figure out the other channels to monetize the user base of free services, as Tencent Music did.

As of today, the most prominent solution to monetizing streaming services are bundled telecom offers. The concept is easy — the premium subscription is offered as a “free” bonus on top of the mobile data plan. That works on two levels. First of all, it allows attracting new paying users into the streaming ecosystem, by selling them a service on a “feels like free” basis. Secondly, streaming subscriptions synergize nicely with the telecom services, since access to the premium raises user’s data consumption.

Besides, it so happens that two of the top-3 local streaming services, JioSaavn and Wynk Music, are owned by (or merged with) telecom providers, Reliance Industries and Airtel, accordingly. Bundled offers create a semi-sustainable financial model for streaming services, even though the market is still very young. Reportedly, on top of the 1% of direct premium subscribers, there are now another 14% of “bundled” users. That 15 % of “paying users account for 55% of all streaming revenue.

However, when it comes to the music industry itself, bundles can hardly bring enough value to turn streaming into a sustainable revenue stream for artists (although some would say that it’s not a sustainable revenue stream even in the US). The cheapest Jio Reliance data plan is priced at just 149 rupees (or about $2,1) a month — and it’s not clear which share of that payment will end up in the pocket of the artist (or at least in the music service’s content pool).

In that sense, bundled subscriptions are more of a short-term solution, a stepping stone on the path to the subscription-based streaming economy. In the long term, however, the streaming market will have to turn to direct subscriptions — and the way it will develop will depend on the competitive landscape of the industry.

Local Streaming Services vs. International Heavyweights

Indian market is the main battleground of the global streaming market. As we’ve mentioned in our Mechanics of Streaming, developed markets like the US are now slowing down in terms of growth — and global services have turned to the emerging market as the primary source of new users.

Earlier this year, Spotify and YouTube Music have entered the Indian market, less than a month apart — and now you probably see why. Counting more than a billion in the potential streaming audience, India is the single largest growth opportunity for the streaming market. Except for China, perhaps — but our guess is that Spotify, YouTube and alike won’t fly with the officials down there.

The global streaming services are met with intense local competition, in the face of JioSaavn, Gaana and Wynk Music, each counting close to 100 million registered users. That is quite a head start, but since we’re talking about a billion-user market, it’s anyone’s guess how it will be split up in 5 years from now. Each of the streaming services has something to offer.

Spotify has its discovery and playlist features and a brand of a global leader, YouTube Music can leverage the 250 million YouTube audience in India, Amazon Music and Apple Music are just a part of a bigger service ecosystem. We’ve laid out the complete classification of the streaming brands and their respective positionings in our Mechanics of Streaming, so check it out if you want to know more.

However; the main question is whether global streaming services will be able to capture the local Indian music context, which is very different from the western canon. As of 2018, international acts accounted for only 20% of all music consumption in the country, and while that share is likely to go up in the coming years, the local catalog will be the key to success in India. And when someone says “local catalog” in the context of Indian music, it means one thing: movie soundtracks.

Bollywood and Film Music

An average Indian movie will feature from 4 to 6 songs fit into the narrative of the film and recorded specifically for that. At the same time, if the US produces around 600 movies per year, India’s output is closer to 2,000 — so that’s around 10,000 original songs produced each year to fit the needs of the film industry.

Approach to film music in India is very different from the conventional movie sync licensing. Here’s how the process works . A movie director and screenwriters will define the song’s place in the script and therefore determine the narrative behind it. Then a music director and a lyricist (or “literati”) will write and compose an original piece of music that fits the setting and the storyline. Then, a professional playback singer will go into the studio to record a song, for actors to lip-synch to in the movie. That’s how film music was produced since the 1930s, and nothing much has changed in that regard.

To understand the role of film music, you need to consider that before the 1990s there was virtually no such thing as non-film music, except for traditional folk artists (which were rarely commercial). The recording industry came about when the vinyl has become widely available and served as a subset of the film industry. It was the secondary market for film music, which was still written as a part of the movie, and not as a standalone product.

That created a 60-year-old pattern of consuming music through film, and that is one of the main factors forming the tastes of the Indian consumer. As Tarsame Mittal of TM Talent Management put it on the Midem Bollywood panel this year:

“If you ask an Indian: “What are the five best songs?” — if they close their eyes, they will visualize the actors that played those songs, not the composers and playback artists”.

Indian consumers traditionally perceive music in its connection with video-content and movie (or at least movie-like) narrative. That fact plays a huge role in the Indian market. However, before we get into it, there are a couple of stereotypes that we’ll need to demystify

Asha Bhosle, one of the most famous playback singers of all time. Throughout her 60+ years career, she recorded over 12,000 songs for over a thousand Bollywood movies

Bollywood vs. Regional Music

First and foremost, Bollywood is just one part of the Indian film industry. The precise definition of Bollywood is “the subset of Indian film industry based in Mumbai and producing movies in Hindi”. At the same time, the Constitution of India officially recognizes 22 different local languages (with Hindi being the most widespread one) and more or less every one of them has its own film sub-industries, with Tamil and Telugu being the biggest ones.

The fact that the word “Bollywood” is often used to signify the Indian film industry can cause a lot of confusion. For example, according to KPMG in India analysis Bollywood music accounted for 50% of all consumption in the country. Another 30% went to regional music, with the remaining 20% attributed to the international repertoire. Comparing the Bollywood’s 50% with 80% from a couple of years ago, it’s easy to conclude that the soundtracks are giving way to independent, artist-centric music model.

Well, that’s not exactly the case. Soundtracks still account for nearly 80% of all recording revenues in India — it’s just that the development of digital infrastructure put the rural music consumer on the map, creating demand for regional music content (literally all music in languages other than Hindi). However, out of that regional repertoire, the lion’s share is still film-music (which is not Bollywood music).

The Sound of Indian Film

Secondly, you have to understand that Bollywood/Film music is not a genre. It’s first and foremost the alternative way of music production, centered around the film industry, which can be applied to all kinds of music. In a way, the top-4 film music companies in India (namely Saregama, T-Series, Sony Music India, and Zee Music Company) are playing the same role as majors do when it comes to western markets.

That is to say, if something is becoming somewhat popular and enjoyed amongst the Indian consumers, soon enough that music will be featured in the Indian movies. So, if you think that Indian film music is all traditional outfits and high-pitched vocals — here’s the lead song of “Gully Boy”, the 4th highest-grossing Bollywood movie of 2019:

Gully Boy, loosely based on the story of Mumbai rappers DIVINE and Naezy, played a huge role in breaking the burgeoning Indian hip-hop scene into the country’s mainstream. Here’s a quick fact: Gully Boy premiered in February of this year. Just six months later, DIVINE, already in a status of a household name in the country, became the first artist signed to the newly opened Mass Appeal India. That case highlights the structure of the Indian music industry.

Role of Soundtrack and the Place of Non-film Music

Some of the articles on the Indian market impose an opposition between the independent and “Bollywood” music industries. That is partially true — the role that Bollywood plays today (and will likely play in the future) means that a significant chunk of the industry is song-focused, rather than artist-focused. Quite often, the artist behind the song (although duly credited) will play a secondary role — much more important is the song itself, the actors that lip-synched to it, the visuals and how it fits into a movie.

However, ask yourself, is it so much different from the increasingly playlist-oriented western streaming context? When it comes to playlists, the artist is also often reduced to just a name in the credits, but the new audiences are well worth it. The truth is that as the digital space grew, Bollywood has become a promotion instrument in the hands of an artist.

Back in the day, people often didn’t even know the names of the playback singers. Today, the performer’s pages are available at JioSaavn at the click of a button. The digital ecosystem has now taken root, and social media created a platform for artists to develop their audiences outside of Bollywood. As a result, the non-film music scene is now on the rise again — for the first time since the pre-piracy era of the 1990s.

However, while digital space has empowered non-film artists to build their story outside Bollywood, the film is still the only channel that can reach the country’s 1.3 billion population. The scope of marketing investment that comes with Bollywood deal is unmatched, so the film remains the destination for any aspiring artist in India. As soon as you spark interest and become somewhat successful in the non-film space, you’re going to get an offer from Bollywood — and artists will rarely say no.

At the same time, you have to understand that film-music is always contracted. Music directors and performers are still just a “work for hire”, and it is the film production company that ends up owning all the rights to the soundtrack. Then, one of the big-4 film music labels will buy the rights from the film company and release it across the digital services.

However, even if playback singers end up stripped of any rights to the song, they will often go to the studio for free. The digital environment allowed for people working on the soundtrack to get noticed, and in that sense, the artist can treat a soundtrack feature as their music video. Just imagine the promotional potential: your clip will be a meaningful part of the movie that will be seen by millions and millions of people, with the actor superstar lip-synching to the song with your name on it.

Film music dictates the current Indian mainstream pop-culture, and work on a major film soundtrack puts the artist’s name on the map — and there are about a thousand different ways in which you can monetize that, from live shows to brand sponsorships to putting out non-film music.

Live Performance and Brand Sponsorships

So, let’s take a closer look at those alternative revenue streams, starting with the live business. The first thing to know is that although the GDP per capita has grown 450% in the last 20 years, the live market has not yet reached the stage where shows can turn a profit off the back of ticket sales alone. Based on our analysis as well as the industry discussions, only 30% of the live revenues are generated by direct ticket sales, and even that can be an overstatement. According to some industry insights, the share of ticket sales might be as low as 10% — and here’s why.

First and foremost, it all comes down to the spending power of the Indian consumer and the price-sensitivity of the market. Promoters have to bring prices down and engage with “buy four tickets — get one for free” type of deals to make the offer a bit more exciting, undercutting the total revenue generated. Whether it be the standalone concerts of the local acts or big festivals, relying on bringing down major international laws (which is expensive in terms of logistics), the amount that consumers are ready to spend on tickets can rarely recoup the costs of putting on a show.

That situation is starting to resolve itself as the ticketing market is getting mature and the customer’s spendings grow, but for now, the live industry has to rely on sponsorships and brand money to sustain itself. Thankfully, live events have a lot to offer to brands that want to associate themselves with artistic values and reach the younger generations of concert-goers. To put it in perspective, the local beer brand Bira 91 planned to put together 50 hip-hop shows in the country throughout 2019 — and that’s just the events directly organized by the brand, while live sponsorships can take all shapes and sizes.

Forming a vicious circle, reliance on sponsorships brings about a second significant factor undercutting the ticketing revenues. Historically, the live industry in India has been influenced by the country’s VIP culture: that is to say that all the people that are somewhat connected with the live show — from officials dealing with licenses to journalists and sponsors — expect to get all the tickets they need for free.

In the end, a considerable share of tickets is just handed out to “important people”, which inevitably makes the people who actually go and buy the tickets seem like second-class citizens. The lost revenues are the smaller part of the VIP malaise — the primary problem is that it makes purchasing tickets something embarrassing. That leads to a paradoxical situation where most of the time the actual paying customers are just an “added benefit”, a secondary market of the live industry.

Quite often a show can do without the tickets sales altogether. Frequently the show will be hosted by a free admission college festival that relies upon sponsorship deals, or, on the contrary, a closed-off private event like a wedding, a corporate show and so on. In either case, the ticket sales are simply non-existent, and that’s how a substantial part of the live shows works.

Crowd At Electric Daisy Carnival India

Opportunities for International Music

Besides, the local market presents a growing opportunity for international artists — and not just the triple-A acts, like Ed Sheeran and Justin Beiber, who’ve been touring India for years now. The market still has its challenges, of course — including its remoteness, lack of spending power, the VIP culture, and so on. However, despite all that, the tier-1 Indian cities have recently seen a wave of successful shows.

In the end, it all comes back to the digitalization of the market. Consider this: in 2018 alone, the internet population in India grew by more than 100 million. 52% of that crowd are under 25 y.o.

Those people are coming online and log into the streaming services, discovering new international acts and new music, and as a result, the local music market is opening-up to many international acts. Following the usual pattern, EDM artists were the first to go on successful Indian tours — and by now Indian audience got a chance to see all of the world’s top-100 DJs.

Now, however, the local industry sees more and more mid-range acts — especially the ones who’ve “planted the seeds” beforehand.

Building upon his trip to India as an opening act for Ed Sheeran’s tour back in 2017, Lauv sold out his Mumbai show in 2019. Jacob Collier’s gig in Mumbai was sold out in under 24 hours — so that promoters had to announce a second night to supply the demand. Just a month ago, Cigarettes After Sex played two back to back shows at the Royal Opera House.

Those are, of course, just isolated cases, but in line with industry discussions, those are the first signs of the new era in the history of the Indian market, where independent international artists can successfully tour the country. For now, in Mumbai — but that’s just a question of time (and economic growth) until more tour destinations sprout up.

The streaming services across the world have already recognized the vast potential held by the Indian market. Perhaps, it’s time the artist and music professionals do the same — the ones who get in there early on might get themselves quite a sweet spot on the 1,3 billion people market.