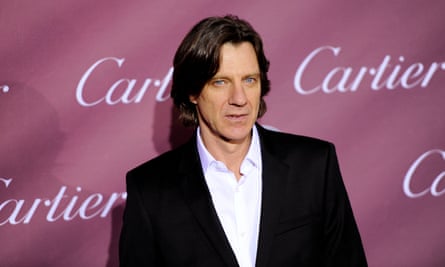

Joshua Oppenheimer

The Texan director’s feature debut, The Act of Killing (2012), and its follow-up, The Look of Silence (2014), explore the aftermath of massacres in Indonesia. Both were nominated for Oscars.

Salaam Cinema, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1995

For this film, Mohsen Makhmalbaf announces a casting call: thousands of people turn up and there’s a riot to get in. Each participant is channelling their worries and hopes into the desire to be in a film. He interacts with them in this dictatorial way, which makes the film ultimately about power and authority. He demands that people cry on command. One woman becomes so frustrated that she does start to cry, so he says OK, you’ve made it. And she’s so happy, but then there’s the disappointment as she realises this was her moment on screen. She thought there’d be a script and a real film to make afterwards. It’s a devastating, beautiful film.

Close Up, Abbas Kiarostami, 1990

A man pretends to be Mohsen Makhmalbaf, the director of Salaam Cinema. He insinuates himself into a family’s life out of loneliness, to make friends. At one point the family realise he’s not really the director and have him arrested. The film follows this man’s trial in an Iranian court, and then the real Mohsen Makhmalbaf meets the man and takes him to the family.

The impostor’s fragility ultimately embodies what it means to be poor and struggling in life, and through that you feel how sad it is that we live in a world where people are measured by wealth and power, and the cruelty that any human being could ever feel insignificant.

Gates of Heaven, Errol Morris, 1978

This was Errol Morris’s first film. He was taking his time with it so Werner Herzog promised “If you finish this film I will eat my shoe,” which he did. It’s about two families in California who run pet cemeteries, and it looks at humans’ relationships to their pets. It’s an odd mystery, a pet. We eat animals, we use them for labour, but then we keep them in our home as objects upon which we project love that we maybe lack elsewhere. Morris has these carefully crafted tableaux: there’s one continuous shot where a woman has a 15-minute lament, complaining about aspects of her life, and that’s where the film becomes something altogether greater and more mysterious.

Loss Is to Be Expected, Ulrich Seidl, 1992

This was made shortly after the fall of communism in eastern Europe and it looks at two communities on either side of the Czech-Austrian border. There’s an elderly man in Austria looking for a new wife, and he meets a lone single woman on the Czech side of the border.

There are these amazing scenes where they go on a date to a funfair and then to a sex museum. She’s much more sexually comfortable than he is, which is a source of incredible comedy. But it’s about desire and love and the fulfilling of our quotidian needs and the necessary, wilful blindness towards our deeper needs because ultimately, to contemplate those needs is to contemplate our own mortality.

The Hour of the Furnaces, Octavia Getino and Fernando e Solanas, 1968

This is a furious, angry film about neocolonialism in Argentina, and it’s the most devastating look at colonialism I’ve seen in nonfiction films. The sections about Argentina’s oligarchy, and the exploitation on which they thrived, are so poetically rendered that you relate to the horror of dictatorship purely through your emotions.

It was made secretly and was screened at illegal opposition meetings, in defiance of the authoritarian rule. People were arrested for screening it. I imagine that seeing it at the time you would come out feeling like you’d have to do something about the situation. There are sections of The Act of Killing where I surely had this film in the back of my head. KB

Lucy Walker: ‘The Up series showed me what the medium was capable of’

British director Lucy Walker has been Oscar-nominated twice, for Waste Land (2010) and The Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom (2011). She is currently working on a follow-up to Buena Vista Social Club.

Hoop Dreams, Steve James, 1994

Hoop Dreams follows two very talented African American boys in Chicago who get a basketball scholarship to go to a prestigious, predominantly white high school. It follows them for five years and it’s a spectacular example of a longitudinal documentary where you get to glimpse the machinery of life. You get a real sense of time unfolding and the big forces that act on us. The twists and turns are subtle, nothing much happens, and yet it feels incredibly dramatic and compelling because it’s so well crafted and the characters are so beautifully rendered. I watched it repeatedly when I was making my first film, Devil’s Playground, because it follows young people through this pivotal period in their lives, and I was trying to understand how you could get so much narrative, emotion and character into a film. There’s a scene where the mum is icing a birthday cake for her son’s 16th birthday. It’s an interview, in the sense that the film-maker is asking her questions and she’s talking to camera, but it doesn’t feel like one, it’s so much more cinematic and compelling and the activity is so perfect.

Streetwise, Martin Bell, 1984

This film had its beginnings in a photojournalism assignment for Life magazine by the photographer Mary Ellen Mark about a group of street kids living in Seattle. She persuaded her husband, Martin Bell, to make a film about them. It’s just so intimate that it’s hard to believe the film-maker is actually in the room with these kids. It’s like he’s put on a cloak of invisibility. I could have chosen any number of cinema vérité masterpieces but for some reason this moves me. I’ve made quite a few films with young people and it’s fascinating because the plot of their lives is so close to the surface: one conversation can change the course of your life when you’re young in a way that is rare when you’re older – and you can capture that nano-second when the course of a life’s direction is altered. When you put a camera and a film crew into a room, the observer’s paradox is almost always true – you can’t capture life because you’re in the way of it. But these kids seem unaware of the camera and they’re behaving in a way that feels like life unfolding. The filmmaker is so present with them, you can’t help but understand what they’re going through, and to understand is to feel empathy and to want to help.

The Five Obstructions, Lars von Trier and Jørgen Leth, 2003

In this underrated film the iconoclastic Danish director Lars von Trier challenges experimental film-maker Jørgen Leth to remake one of his earlier films, The Perfect Human, five times, each time with a different creative constraint. The first “obstruction” imposed by von Trier, for example, was that the film had to be made in Cuba, using shots of no more than 12 frames. Another was that it had to be made as a cartoon. It’s basically these two creative egos going up against each other and it gives a fascinating insight into the film-making process, what goes on in a director’s head and how you cope with stress and constraint and challenge. It’s delicious and playful and there’s never a dull moment watching these two maestros needling each other.

The Gleaners and I, Agnès Varda, 2000

This film was made during the early days of the hand-held digital camera, when for the first time you could capture something high-quality enough to show on a big screen on a camera that would fit in your handbag. It’s an essay about the people who pick through other people’s leftovers, whether it be the remains of the harvest in the countryside, or in cities. It’s very casual, but Varda is so astute and the quality of the film-making is such that it becomes something very beautiful, a meditation on life. We’re having this golden age of documentary right now and it’s being driven by technology. In the past you would need to write a script first because the editing process was so laborious but now you can shoot a whole bunch of stuff and capture life in a way that you couldn’t before and this film, shot by a 72-year-old woman using a very low-key format, shows you just what level of artistry is possible.

Up series, Michael Apted, 1964

I’m fascinated by longitudinal film-making and this series, which has followed the lives of 14 British children since 1964, when they were seven years old, showed me what the medium was capable of. This series is head and shoulders above any other attempt to record dramatically a whole human life. And because it’s a whole group of people, you learn not just about the individual but also about the system in which they’re living. I can’t think of any other artefact in our culture that can tell us so much about Britain in our lifetime and how society is evolving as this body of work. It’s illuminating and fascinating and it’s one of the things that inspired me to do the work that I do. JO’C

Alex Gibney: ‘Fake home movies don’t bother me – you might as well object to dreams’

Alex Gibney’s award-winning films include Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005), Taxi to the Dark Side (2007) and Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God (2012). Last year he released documentaries on Scientology and Steve Jobs. He says: “I don’t believe in ‘five best films’. But I do believe in influential films. These are five of mine.”

Night and Fog, Alain Resnais, 1955

What really impressed me about this film was its concision. It’s about the Holocaust, but it has a simple and horrible beauty to it, because it describes the terrifying nature of the Holocaust through a powerful series of images and a narration that was specific, naming the collections of items of the prisoners and survivors. It’s the cruel poetry of detail that is so heartbreaking: the handles of the ovens, the fingernail scrapings on the ceilings of the cells. We see piles of combs, shaving brushes, shoes and a vast mountain of human hair. It took something so horrible but found a way to go to the heart of the matter through simple details.

Gimme Shelter , Albert and David Maysles, Charlotte Zwerin 1970

Here you see the Rolling Stones on tour singing about sympathy for the devil, but their posturing about satanism blows back at them at the Altamont music festival. It’s structured like a detective story: it starts with a murder – a Hell’s Angel stabs somebody who seems to have a gun in the audience – and then you go back in time. Maybe one of the most powerful scenes is of the Stones listening to a playback of Wild Horses in the studio. It’s stunning in its simplicity. That film went way beyond a concert show; it celebrates music but it’s really about a moment in time and how dark forces get unleashed. It’s powerful both in its observation and its analysis, which is a rare combination.

When We Were Kings , Leon Gast, 1996

This is maybe the greatest sport film ever made. It has wonderful cinema vérité footage of the “Rumble in the Jungle”, the famous 1974 fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. Gast has the most magnificent material, particularly in Muhammad Ali on a run, dancing, gooning for the camera, at his most charismatic. And then the brooding figure of George Foreman. But Gast wasn’t able to put that footage together, and in comes Taylor Hackford, shoots some interviews with people who were there, notably George Plimpton and Norman Mailer, and through their recollection you also have a sense of analysis and understanding rather than mere observation. So it’s combining those two things in the film that really is magnificent.

Stories We Tell, Sarah Polley, 2012

This is a detective story that’s very much in the first person. It’s about identity, trying to understand your childhood, and ultimately paternity. Sarah Polley is digging back into the relationship between her mother and father, who she discovers isn’t her biological father. In some quarters she was criticised for using a series of fictional home movies that she manufactured, but it didn’t bother me at all – they might as well object to dreams and memories, because those are everyday recreations. The trick is finding the poetry in them. It’s a very powerful film about memory and exploration and love, because she comes to appreciate her adoptive father in a way she might not otherwise have done.

Waltz With Bashir , Ari Folman, 2008

Part of the small but growing category of the animated documentary, Waltz With Bashir is really a film about repressed memory, and the recollection of Israeli soldiers trying to understand why they’re having these nightmares. The idea of using animation to convey what is mostly going on inside their heads, in their imaginations, is such a powerful one. It doesn’t become clear until almost the end that the soldiers all took part in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp massacre in Lebanon in 1982. And the very end of the film includes just the slightest bit of real footage: a woman wailing in the wake of that massacre. It really is one of the most poignant films about the trauma of war. KB

Kim Longinotto: ‘All the good TV documentaries are on the BBC at the moment’

British film-maker Kim Longinotto tackles themes such as female genital mutilation (The Day I Will Never Forget) and women fighting abuse (Sisters in Law). Her most recent film, Dreamcatcher, is on Chicago women trying to leave the sex industry.

Sherman’s March, Ross McElwee, 1986

I saw this at film school, then watched it again at a festival a couple of years ago and thought it was so charming, so good. It has a very simple premise. The director is meant to be making a film about General Sherman’s march through Georgia during the American civil war, but he falls out of love with the idea. Instead, the film becomes about his attempts to find a girlfriend, shot as a kind of video diary – an approach that was completely new at the time. It’s so candid and affectionate and lovely, and everyone at the festival loved it. Not many films bear rewatching, but this one does.

Tales of the Grim Sleeper, Nick Broomfield, 21

Nick Broomfield has become much more serious and political in recent years and this is a difficult and committed film. It’s about a man who was arrested in 2010 for killing as many as 100 prostitutes in Los Angeles over a period of 25 years. What’s extraordinary is how he managed to get away with it for so long – the police didn’t pursue because his victims were mostly black prostitutes. It’s a very timely film, in terms of Black Lives Matter and police abuses in the US, and I thought he got it just right. It’s also a really good crime story.

Solar Mamas, Jehane Noujaim and Mona Eldaief, 2012

This is a film about Bedouin women trying to get solar energy in their village in Jordan. It follows one woman travelling to a college in India to become a solar engineer. I like it because it’s not saying, “Oh, look at these poor women.” Instead, it shows women actively changing their lives and I found that very inspiring. So many documentaries tell you what to think. This one doesn’t – it puts you straight into the story and you get to know the characters just by watching them. It was part of a very good BBC series on poverty. That’s where all the good TV documentaries are at the moment: on the BBC.

Virunga, Orlando von Einsiedel, 2014

I watched this in the cinema, which was good because it’s very beautifully filmed – a real spectacle. It’s set in a reserve in the Congo, which is home to the last mountain gorillas on earth and it follows the people who are trying to save them, as well as the corrupt people trying to get the land to drill oil. There’s a moment when the people in a neighbouring village are attacked. It was filmed so well, I don’t know how they did it. You’re right in the thick of it and you feel so angry, because you know it all comes down to corruption and greed.

Five Broken Cameras, Emad Burnat, Guy Davidi, 2011

This is about a Palestinian man who films the destruction of his village’s olive groves by the Israeli army. His cameras keep getting broken by the Israelis, hence the title, but he just kept filming. I think he was feeling: “There’s an incredible wrong being done to my people, I’m going to film it, even if I die doing it.” Then he linked up with an Israeli film-maker, who edited the footage. I remember people saying he shouldn’t have worked with an Israeli, but I thought it was so great that they came together and made something very powerful which showed us what is really going on in Palestine. KF

James Marsh: ‘In my view there should be no boundaries to film-making’

James Marsh is a British film-maker, best known for the Oscar-winning documentary Man on Wire (2008) and the acclaimed Stephen Hawking biopic, The Theory of Everything.

Man with a Movie Camera, Dziga Vertov, 1929

This was the first truly subversive, playful documentary. It’s notionally a day in the life of a city in the Soviet Union and so it has, on a purely sociological/historical level, great value. But what it does beyond that is to show you the means of production: the filming, the cutting room, the editing – all the things that are going into the making of this film. It’s way before its time, the Tristram Shandy of documentaries, if you like. It’s so inventive and it has techniques that, 87 years later, still look pretty revolutionary: the freeze frames and slow motion. It’s just full of inventive and brilliant formal ideas as well as being a very beautiful film to watch. And it’s informative too, showing us the Soviet Union in a halcyon period before Stalin’s terror, when you felt that things were still possible in a new political context. Of course we now know that Vertov suffered in the Stalin era, as many other independent artists would have done, but there’s a sort of optimism and a playfulness to it that you wouldn’t expect from a Soviet documentary from 1929.

Le Sang des Bêtes, Georges Franju, 1949

This is a documentary about an abattoir that was made in Paris just after the second world war. If the film had been shot in colour it would be unwatchable, it’s so gory and weird and disturbing, but it’s in black and white and so it becomes a bit more abstract. There are images in that film that I think are some of the most powerful I’ve ever seen. There’s a surreal sequence where lots of sheep have been beheaded and they’re all dancing without their heads on this conveyor belt. It’s like a bit of choreographed horror, but it’s all real. The director Georges Franju went on to have a career doing very artistic horror movies in French cinema, most famously a film called Les Yeux Sans Visage.

The War Game, Peter Watkins, 1965

In this film, Watkins takes a possible scenario – a nuclear attack on London – and shows you very carefully, each step of the way, what is likely to happen. It was banned by the BBC for many years because it was just too harrowing a depiction of a reality that everyone at that time was very concerned about: this was in the middle of the cold war and at the time there were dozens of warheads pointing at us. It’s like a documentary made by Brecht – you’re staging something to flush out a reaction in the audience, and that reaction is one of utter horror. Some people would say this is not a documentary because everything was staged, but it’s a speculative documentary – the director is saying: “This is how it could be and I’m going to show you this in a way that’s very truthful.” It’s very responsible, even if the imagery is very disturbing: you’re seeing bobbies firing at people in the street, people with their clothes burned off. His information is sourced directly from the government and based on scientific fact, so the bed of it is factual, and people responded to it as if it were a real documentary.

It’s a brilliant and bold piece of film-making. He’s reinventing the documentary and subverting it. In my view there should be no rules and no boundaries to film-making, and the impact this film had shows you how much he got right.

The Battle of Chile, Patricio Guzmán, 1975, 1976, 1979

This is a trilogy of films that chronicles the coup against the democratically elected leftwing government of Salvador Allende. It shows you the breakdown of a society and the triumph of the greater evil once there’s a political vacuum, so it’s a very strongly political film but it’s also, dare I say it, incredibly exciting. For me, this is the first great example of a film-maker being there while it’s all actually happening and there are moments in it that are utterly heartbreaking. Notoriously, there’s one point where they are filming a demonstration and you hear a gunshot and you see the camera just fall down and tip over and the cameraman has been shot and killed. That shows you the terror of these situations, where no one is safe from the forces of darkness, but also the commitment of the film-maker to document this, to extract a proper historical document from these terrible events. It’s a work of great bravery and definitive historical significance.

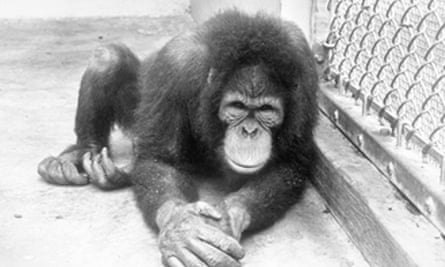

Primate, Frederick Wiseman, 1974

Wiseman is probably my favourite film-maker in fiction or nonfiction, and Primate meant a lot to me because I made a film [Project Nim] that emerged from some of its ideas. It’s a portrait of a primate experimental laboratory in Texas and there’s imagery that you cannot forget. You see operations on animals that are still alive, their brains being looked at while they’re still twitching around, so it’s very disturbing and upsetting. It’s an interesting window on the hubris of science, which does things for its own sake because it can do them. A lot of the experiments done in this laboratory seem utterly pointless.

Wiseman is a purist. He doesn’t use commentary, he doesn’t use music, he doesn’t use interviews, he just observes things and then finds a rhythm in his cutting room to show you the reality, usually of an institution, and the human fallibilities of institutions. Primate is really about the humans, not the animals. The animals hold a mirror up to people in that institution, and we don’t pass that test very well. J’OC

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy: ‘Documentaries can change the way people look at things’

The journalist and film-maker Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy was born in Karachi, Pakistan. Her films Saving Face (2012), about acid attacks in Pakistan, and A Girl in the River (2015), which tackled the subject of honour killings, both won Oscars for best short subject documentary.

Amy, Asif Kapadia, 2015

It’s so rare that someone’s life has been so well documented. From when Amy Winehouse was very young right up to the time she died, people were filming her: her family, her friends, the media. I absolutely loved the way Asif Kapadia told her story using all that footage – as if he was with Amy her whole life. As a viewer, you really get to know her and understand what she went through. You’re cheering her on, hoping that she does get over her addiction, does beat the paparazzi, does come out on top. The film made me realise how much of her life was not in her hands.

Iraq in Fragments, James Longley, 2006

I was amazed that this film was shot on a camcorder, because it was so beautiful and it showed Iraq in a completely different light. All the images coming out of Iraq at the time were images of war. This showed what everyday life felt like – it was almost as if the director was shutting the war out. You felt the violence, but he doesn’t show it. The film records three different perspectives. One storyline follows a young Sunni boy without a father in Baghdad, another shows you the followers of the Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr in the south, and in the third you’re with a Kurdish family in the north who are happy the Americans are there. It also tracks how Iraq has changed from one generation to the next.

Buena Vista Social Club, Wim Wenders, 1999

Cuba was a mystery to many people when this film was made. It was under sanctions and closed off to the US. With Buena Vista Social Club, it was as if Wim Wenders put aside the sanctions, the politics, and played with the language of music. These musicians and their stories moved people, whatever their politics. The film put you on the streets of Havana, you saw how people ate, how they interacted with each other, the way they danced and sang. Even without being political, the film is political, because it shows you what life was like inside Cuba at a time when the only perspective you got on the country was through a news lens.

The Thin Blue Line, Errol Morris, 1988

This film showed me that documentaries can change the way people look at things. It’s centred on a murder that took place in 1976: a young man stole a car, picked up a hitchhiker called Randall Adams and later a policeman was shot and killed by someone in the car. Adams was given a life sentence for the murder but Morris’s documentary showed, by exploring the testimony and the way the police put the case together, that he had been wrongly accused. A year after the film came out, Adams was released from prison. That was the bit about the movie that really shook me. It oscillated between art and activism. It was a gripping drama but it also had an impact in the real world.

Bowling for Columbine, Michael Moore, 2002

This was a landmark film for me because it made documentaries popular – people who didn’t normally watch documentary films watched this. It tells the story of the Columbine high school massacre and the investigations that followed, but more than that it tells you about the National Rifle Association, about gun violence, about how schools in Michigan had become battlegrounds. His interview with Charlton Heston, who was the NRA’s president at that time, was very powerful and I remember the scene where he goes into a bank and gets a free hunting rifle for opening an account. On the way out, he asks: “Do you think it’s a little dangerous handing out guns at a bank?” He told the story beautifully and he asked the questions a viewer would want to ask. KF

Franny Armstrong: ‘By the end of Some Kind of Monster, I quite liked Metallica’

Franny Armstrong is the UK director of The Age of Stupid, a reflection from 2055 on climate change, McLibel, about the McDonald’s court case, and Drowned Out,, on the fight against the Narmada dam.

Global Report, Peter Armstrong, 1981

This was a BBC documentary made by my father in the 1980s. I remember he took me on a trip to New York when I was eight years old and I ended up watching it over and over again. It just really blew my mind. I’d never been out of the UK and suddenly I was seeing this extreme wealth on show in New York and at the same time being hit by the extreme poverty in my dad’s film. I’ve chosen it because I think that’s where my whole drive to change things for the better came from. It shows five different stories from different parts of the world. It’s a bit similar to Unreported World, but back then it was considered groundbreaking. It was telling the stories that the rest of the media weren’t telling and the one that stuck with me was the story about a little boy my age in India who was having to sell peanuts on the side of the road in order to make money for his family. That was my introduction to the concept of inequality.

The Queen of Versailles, Lauren Greenfield, 2012

Inequality is obviously one of the key issues of our time and I think this is the best film I’ve seen on the subject. The film-makers were following this mega-rich American family, the Siegels, who were building the biggest house in the United States – a mansion in Florida inspired by Versailles – and then the financial crash happens and they lose lots of money and they can’t finish it. They’ve got lots of children who are being looked after by a Filipina nanny, who we learn hasn’t seen her own children for years because she can’t afford a ticket to go home. The thing that really stayed with me was when the children’s pet lizard dies because nobody had fed it and it turns out that they didn’t even know they had a pet lizard because they’re so overwhelmed with material possessions. Everyone in the film is unhappy, the ones who’ve got too much stuff and the woman who can’t see her own kids. It’s an amazing example of the story of a major global issue being told in a very small way, in this case through a dead lizard.

Blackfish, Gabriela Cowperthwaite, 2013

This is perhaps an odd choice, because I haven’t actually seen it as I find the subject matter too upsetting, but I’ve chosen it as an example of a documentary that sets out to change something material and succeeds. It’s about Tilikum, a performing killer whale being kept in captivity at SeaWorld. In the last few weeks, SeaWorld has announced that it will no longer breed orcas in captivity or acquire any new ones. It shows how one extremely powerful documentary can work alongside campaigning and holding demonstrations to bring about change.

Lessons of Darkness, Werner Herzog, 1995

Lessons of Darkness is by the far the most powerful anti-war film I’ve ever seen. It was shot just after the first Gulf war, when the Iraqi oilfields were famously set on fire. The film is essentially just a continuing aerial shot of these burning oilfields set to beautiful music. It’s completely mesmeric and beautiful in an apocalyptic way, and it just goes on and on. You can’t believe how big, how many and how endless these oilfields are, or how wanton the destruction is. And just when you’re thinking “OK, I’ve had enough” it cuts to a mother and a child and the mother just tells the story of what happened to her family during the war, and then she says, of the boy who is about five years old: “This child has never spoken again.” And that’s all there is to the film. It’s so bold. You have to be Werner Herzog to get away with that.

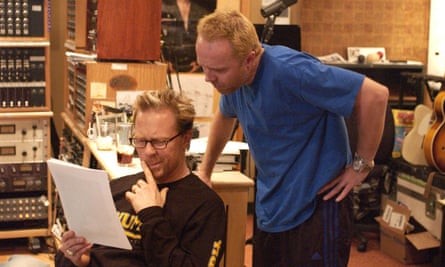

Some Kind of Monster, Joe Berlinger, Bruce Sinofsky, 2004

I’ve chosen this as a bit of light relief, because it’s rip-roaring fun. The film follows the heavy metal band Metallica as they go through group therapy. God knows how the directors ever got permission to do it, but it’s just so incongruous to see these ageing rockers discussing their personal problems in such an open way. What strikes you is the difference between their tough image and music and the pettiness of their squabbles over who gets the most credit on a record. It follows them over a couple of years while they’re rehearsing a new album and searching for a new bass player, but you also get to see them trying to balance their personal lives with being heavy metal performers – you see one of the band members going to his daughter’s ballet class, for example. It’s way more absurd than Spinal Tap, but what’s most strange is that by the end of it I actually quite liked their music and I’m really not a heavy metal fan. J’OC

Khalo Matabane: ‘Some film-makers try to be objective, but Herzog isn’t shy’

Khalo Matabane was born in Limpopo, South Africa. His documentaries include Nelson Mandela: The Myth and Me and Story of a Beautiful Country, a road movie that explores post-apartheid South Africa.

When the Levees Broke, Spike Lee, 2006

I saw this four-part documentary in a single night at a friend’s house in Amsterdam and I was completely blown away. It’s an angry, in-depth look at how the levees failed in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina and what happened in the aftermath. It really moved me and gave me an insight into race relations in the US and what it means to be poor in a developed nation. The images of bodies floating in the water and people trying to save themselves and their neighbours have really stayed with me, and the music by jazz trumpeter Terence Blanchard – who also appears in the movie – is really memorable.

Capturing the Friedmans, Andrew Jarecki, 2003

This felt more to me like fiction than documentary – I remember watching it and thinking, can these people be real? It’s about a father and son in Long Island who were convicted of molesting children in the 1980s. The film-maker Andrew Jarecki discovered that the family had an archive of home movies from the time, documenting how they coped with the accusations and the trial. What amazed me was the access: I’ve always been curious how Jarecki managed to persuade the Friedmans to bare their souls and let him use the videos. The result is a disturbing portrait of a very unconventional family.

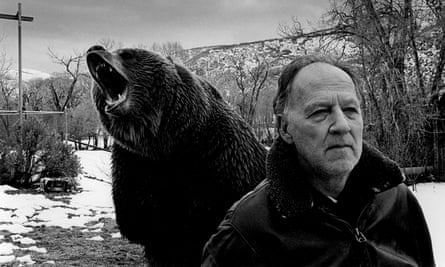

Grizzly Man, Werner Herzog, 2005

What I remember most from this documentary is Werner Herzog’s voice. Ostensibly this is a film about a man called Timothy Treadwell, who spent many summers living among grizzly bears in Alaska and was eventually mauled to death and eaten by an enormous brown bear. Herzog turns it into a much grander meditation on loneliness and man’s relationship with nature. Many film-makers try to be objective and avoid giving their opinions, but Herzog isn’t shy about being authoritative. When he addresses the camera directly in that strange monotone of his, it’s almost like you’re listening to the voice of God.

The 3 Rooms of Melancholia, Pirjo Honkasalo, 2004

I saw this at a film festival in Amsterdam and it had a huge impact on me. It confronts you with images of war from Chechnya, with a particular focus on the children caught up in the conflict (the second Chechen war that began in 1999). It’s incredibly sad but I really liked that it didn’t try to push a war-is-bad message on you, like a Michael Moore film. It just provides testimony and lets you make up your own mind. I was also struck by the artistic nature of the film-making and how images of war and catastrophe can also be beautiful. I’m sure people had problems with that, but it meant the images stuck with me long after I saw the film.

Pina, Wim Wenders, 2011

I didn’t know anything about Pina Bausch or contemporary dance before I saw this film – I only went to see it because Wim Wenders directed it. The fact that I really enjoyed it and didn’t want it to end just goes to show what power documentaries can have. Pina Bausch died just as Wenders was preparing to make a film about her, so instead he filmed her dance troupe in Germany talking about Pina and re-enacting her work. One detail I really loved was the way he disconnected the voiceovers from the images of the people who are speaking. It added to the film’s very strong emotional effect. KF

Molly Dineen: ‘Adam Curtis made us look again at our own world’

Born in Canada and raised in Birmingham, documentary director and cinematographer Molly Dineen won Baftas for her 1993 series The Ark and 2007 film The Lie of the Land, and Royal Television Society awards for 1987’s Home from the Hill and 1989’s Heart of the Angel.

Into Eternity, Michael Madsen, 2010

I saw this when I was on a jury at a documentary festival in Nyon, and it was really unexpected. It’s about Finland burying its nuclear waste in a deep, deep cavern, with two diggers silently burrowing into the bedrock. That’s intercut with interviews with scientists talking about how you can leave a signal for future civilisations not to go into this burial chamber. This stuff is so toxic for 100,000 years, so we’re not talking about any sort of signposting we will understand; there may be whole different ways of communication. There was something really affecting about that. And the interviews are fabulous, because they’re very unpromising – just straight-on head-and-shoulders shots of scientists – but they’re humorous and warm and compassionate.

Le Joli Mai, Chris Marker and Pierre Lhomme, 1963

They showed this to us when I first went to the National Film School and I absolutely loved it. It’s about the beautiful month of May in Paris, and it starts with a voiceover by actress Simone Signoret, saying as only French people could, “It’s the most beautiful city in the world and against this set, 8 million Parisians act out a play.” And it’s this fantastic springboard into a series of observed vignettes: famous people, shopkeepers, passers-by, mothers, sons, black, white, men, women.

It’s like a wonderful complex tapestry – without wanting to sound like a pillock – of life. And this was the first time France hadn’t been at war since 1939, so there’s this beautiful feeling about it.

Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer, Nick Broomfield And Joan Churchill, 2003

This is the last interview with Aileen Wuornos [who killed seven men in Florida in 1989-90] before she’s executed. There’s a very interesting tension as to whose film it is. She sees it as her opportunity to set the record straight, saying it was self-protection – I thought she came across well and I was incredibly moved by her situation. But on the other hand Nick and Joan are making the film about her. At the end it’s very shocking because he asks her a question she doesn’t like and she’s screaming, “fuck you, Nick”, as she’s dragged off to be executed. And yet you feel it’s something he had to ask, because I suppose in a documentary you have to have the film‑maker in charge.

The Power of Nightmares, Adam Curtis, 2004

I think that Adam Curtis is a completely independent voice, and he presents situations and current affairs back to us in a radical way. The Power of Nightmares is a three-part BBC documentary where he addresses al-Qaida and the fact that it’s been very useful for governments to have something to be scared of. In the context of the whole world being terrified of al-Qaida, this made you rethink received opinion; he made us look again at our own world.

I love his delivery and the way he uses archive material and music. His style is so unusual and imaginative and rich and draws on all sorts of other cultural references that we have.

Sisters in Law, Kim Longinotto, 2006

This is about two female judges in Kumba, Cameroon dealing with cases of violence against women. Kim Longinotto and I work in a very similar way, so I think I appreciate her films even more. It’s difficult to immerse yourself in another culture, and in a different language, when to a European this is a very alien community. Kim always puts herself out to the nth degree: she manages to be in the right place and observe and tell the story through character. I think it’s because of her character – she’s warm, she’s humble, she’s sensible – that she relates to people so well, and boy, does it come across here. It’s a brilliant film. KB

Angus Macqueen:‘Television’s contribution to the documentary form has been huge’

Angus Macqueen is a British film-maker whose latest film is The Legend of Shorty (2014), about the search for Mexican drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. Other films include Gulag and The Death of Yugoslavia.

Man on Wire, James Marsh, 2008

This is the story of an event in 1974, when a French tightrope-walker named Philippe Petit decided to sling a wire between the Twin Towers in New York and walk across it. It’s not an easy story to tell on film, but they did an extraordinary job. I loved the decision to shoot it like a heist movie, showing how Petit and his gang staked out the towers and set up the rope without anyone noticing. The director got across the lunatic absurdity of the whole project and the sense that Petit’s walk was not just a physical feat but also an act of art. Too often, documentaries are painful and difficult to watch, but this was a real pleasure.

Little Dieter Needs to Fly, Werner Herzog, 1998

This is one of Werner Herzog’s less well-known documentaries. It’s an astonishing story about a German-American military pilot called Dieter Dengler who grew up in Germany during the second world war, then went to America, enlisted in the air force and fought in Vietnam. He crashed his plane over Laos and was taken prisoner by Laotian troops, then handed over to the Viet Cong. Herzog takes him back to revisit the whole ordeal and meet his former captors. It’s a remarkable piece of documentary film-making. Herzog later turned the story into a feature film called Rescue Dawn, which wasn’t very good. This is the one you need to see.

Shoah, Claude Lanzmann, 1985

This is Claude Lanzmann’s nine-hour film about the Holocaust. My film Gulag was pretty directly inspired by it, though I would never claim to any of its greatness. What’s remarkable about Shoah is its monumentality: Lanzmann wanted to make a monument out of a documentary, and he didn’t care if you thought it was too long because the extraordinary nature of this event – the organised, mechanical destruction of human beings over an extended period of time – cannot be told in 45 minutes or an hour. It’s painful to watch but magnificently made. His meeting with Jan Karski, the Pole who reported what was going on in the Warsaw ghetto to the allied governments, is almost a film in itself. Lanzmann also finds some of the perpetrators and gets them to talk. Once you’ve seen it, it’s impossible to forget.

Pandora’s Box, Adam Curtis, 1992

I think Adam Curtis is in many ways the most important documentary voice on British TV, simply because he puts across mad arguments and compels you to engage with them. This was his first series for the BBC (his best known is probably The Power of Nightmares) and his imaginative use of archive material is completely striking. The subtitle is “A Fable from the Age of Science” and it deals with a lot of things he’s fascinated by – communism, game theory, DDT, nuclear power – weaving them together in a very original way. It’s really worth seeing if you can find it.

China: Beyond the Clouds, Phil Agland, 1994

This is a great documentary series made in China in the early 90s. Agland was an anthropologist and he’d already made a wonderful series in the 80s about the Baka tribe in Cameroon. For Beyond the Clouds, he spent several years in a small town in Yunnan province telling the stories of various characters he met. He focuses on normal people but in doing so tells us about China’s past as well as its present and the monumental change that was coming. It was beautifully shot, because he’s a very fine cameraman, and very memorable. Television’s contribution to the documentary form has been huge and this is television at its best. KF

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion