-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Robert J Collier, Lance H Baumgard, Rosemarie B Zimbelman, Yao Xiao, Heat stress: physiology of acclimation and adaptation, Animal Frontiers, Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2019, Pages 12–19, https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfy031

Close - Share Icon Share

Climate is the biggest single factor affecting animal production.

Acclimatization is a coordinated phenotypic response to environmental stressors and the response will decay if the stressors are removed.

Acclimatization occurs in two phases; short term (acute stress response) and long term (chronic stress response).

The acute phase acclimatization response is under homeostatic regulation and the chronic phase response is under homeorhetic regulation.

If chronic stress persists over several generations, the acclimatization response will become genetically “fixed” and the animal will be adapted to the environment.

Introduction

Climate is the most important ecological factor determining the growth, development, and productivity of domestic animals (Adams et al., 1998). Climate changes impact the economic viability of livestock production systems worldwide (Klinedinst et al., 1993) through a variety of routes. These include changes in food availability and quality, changes in pest and pathogen populations, alteration in immunity and both direct and indirect impacts on animal performance, such as growth, reproduction, and lactation. Lack of prior conditioning (acclimatization) to sudden change in weather often results in catastrophic losses in the domestic livestock industry (Thornton et al., 2009)

Despite uncertainties in climate variability, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report identified the “likely range” of increase in global average surface temperature between 0.3 °C and 4.8 °C by the year 2100 (IPCC, 2014). The risk potential associated with livestock production systems due to global warming can be characterized by levels of vulnerability, as influenced by animal performance and environmental parameters (Hahn, 1995). As production levels (e.g., rate of gain, milk production per day, eggs per day) increase, the sensitivity and tolerance to stress increases and, when coupled with an adverse environment, the animal is at greater risk.

Nationally, heat stress results in total economic losses ranging between $1.9 and $2.7 billion per year (St-Pierre et al., 2003). Although projected increases in ambient temperatures will result in additional financial losses, the extra metabolic heat resulting from the projected increase in animal productivity will have far greater impact, which has been estimated at between two and four times as much as global warming (St-Pierre et al., 2003; St.-Pierre, 2013).

Our understanding of the mechanisms by which environmental stress reduces productivity of domestic animals has greatly improved over the last century (Collier et al., 2017). However, it has been difficult to genetically alter production animals to improve their tolerance to thermal stressors. For example, decades of research using genetically defined populations demonstrated that using conventional crossbreeding approaches to improve resistance to thermal stress in the dairy industry always resulted in lower milk yields in the F1 generation, the same holds true for live weight gain in meat animals (Branton et al., 1974; Frisch and Vercoe, 1977).

Therefore, improving productivity in animals exposed to adverse environmental conditions during the last quarter century focused on modifying the environment and improving nutritional management while applying selection pressure on improving yields rather than improving stress resistance. This approach dramatically increased productivity of domestic animals but also increased their sensitivity (reduced their thermal plasticity) to high temperatures in general because of their greater internal heat load.

The purpose of this review is to define processes by which domestic animals respond to changes in their environment. These processes are critical to survival but often negatively impact productivity and profitability of livestock operations. However, understanding how these processes are controlled offer opportunities for improving thermal stress resistance.

Thermal Regulation

The thermal strategy of mammals and birds is to maintain a body temperature above the surrounding ambient temperature which allows them to dissipate heat through three mechanisms requiring a thermal gradient (conduction, convection, and radiation); collectively referred to as sensible routes of heat loss. When the thermal environment meets or exceeds the animal’s body temperature these routes of heat exchange are lost, and the final/only remaining route of heat loss is through evaporative routes (sweating and panting) which require a vapor pressure gradient and dictate that relative humidity is a major factor controlling rate of evaporative heat loss. Routes of energy exchange (sensible heat and evaporative heat) are fixed by the laws of physics. However, variability among animals in body size, fat deposition, hair coat, functional activity, level of production, and number of sweat glands, as well as the presence or absence of anatomical respiratory countercurrent heat exchange capability, has led to specialization of heat exchange among domestic animals. For example, some use conductive energy exchange (swine) or respiratory exchange (ruminants, poultry), whereas horses have extremely high sweating capability (Collier and Gebremedhin, 2015).

Animals are most productive inside a range of temperatures referred to as the thermal neutral zone. When animals are exposed to conditions outside of the thermal neutral zone (cold or heat stress) they must expend energy to maintain euthermia. The temperatures at which this occurs is referred to as the upper and lower critical temperatures. The upper critical temperature is always below body temperature because of the requirement for a thermal gradient to dissipate heat by sensible routes of heat loss (conduction, convection, and radiation). As shown in Table 1, the upper and lower critical temperature of dairy cattle changes with body size, age, and level of production.

Effect of age and physiological state on critical temperatures of dairy cattle

| . | Critical temperatures . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological status . | Lower (°C) . | Upper (°C) . | Set point (°C) . |

| Calf (4 liters milk daily) | 13 | 26 | 38.5 |

| Calf (50–200 kg, growing) | −5 | 26 | 38.5 |

| Cow (dry and pregnant) | −14 | 25 | 38.5 |

| Cow (peak lactation) | −25 | 25 | 38.5 |

| . | Critical temperatures . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological status . | Lower (°C) . | Upper (°C) . | Set point (°C) . |

| Calf (4 liters milk daily) | 13 | 26 | 38.5 |

| Calf (50–200 kg, growing) | −5 | 26 | 38.5 |

| Cow (dry and pregnant) | −14 | 25 | 38.5 |

| Cow (peak lactation) | −25 | 25 | 38.5 |

Adapted from Collier et al. (1982).

Effect of age and physiological state on critical temperatures of dairy cattle

| . | Critical temperatures . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological status . | Lower (°C) . | Upper (°C) . | Set point (°C) . |

| Calf (4 liters milk daily) | 13 | 26 | 38.5 |

| Calf (50–200 kg, growing) | −5 | 26 | 38.5 |

| Cow (dry and pregnant) | −14 | 25 | 38.5 |

| Cow (peak lactation) | −25 | 25 | 38.5 |

| . | Critical temperatures . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological status . | Lower (°C) . | Upper (°C) . | Set point (°C) . |

| Calf (4 liters milk daily) | 13 | 26 | 38.5 |

| Calf (50–200 kg, growing) | −5 | 26 | 38.5 |

| Cow (dry and pregnant) | −14 | 25 | 38.5 |

| Cow (peak lactation) | −25 | 25 | 38.5 |

Adapted from Collier et al. (1982).

It is clear from Table 1 that although the set point remains the same throughout life and the upper critical temperature drops slightly with age and production, the big change is the drop in the lower critical temperature with increase in body size, insulation, and heat associated with metabolism of production. These factors decrease the lower critical temperature making animals more resistant to cold and less tolerant to heat.

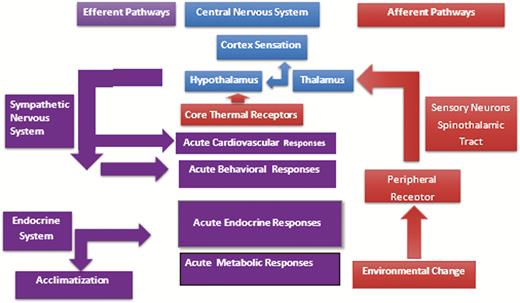

Thermoregulation is a neural process that connects information from the external and internal thermal environment to an appropriate efferent response (e.g., vasoconstriction, raising and lowering hairs or feathers, panting), which permits the animal to maintain a stable internal environment relative to a variable external environment (Nakamura and Morrison, 2008). These efferent autonomic pathways also provide the connection between the external environment and cellular metabolism by directly regulating cellular metabolism and endocrine system activity (Collier and Gebremedhin, 2015; Figure 1).

Schematic of neural integration of environmental conditions with animal metabolism. Adapted from Collier and Gebremedhin (2015).

Thermal Stress

Stress is defined as an external event or condition which produces a “strain” in a biological system. When the stress is environmental, the strain is measured as a change in body temperature, metabolic rate, productivity, heat conservation, and/or dissipation mechanisms. Thermal stress is triggered when environmental conditions exceed the upper or lower critical temperature of domestic animals requiring an increase in basal metabolism to deal with the stress.

Animals mount a response to a stress that involves behavioral, metabolic, and physiological changes at multiple levels of vertebrate organization from subcellular to the whole animal (Collier and Gebremedhin, 2015). The systemic response to environmental stress is driven by two systems—1) the central nervous system and 2) peripheral nervous system and endocrine components (Figure 1) (Charmandari et al., 2005). The central component involves nuclei in the hypothalamus and brainstem which release corticotrophin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin. The peripheral components of the stress system include the pituitary–adrenal axis, the efferent sympathetic adrenomedullary system and components of the parasympathetic system (Habib et al., 2001). However, relative to environmental stressors and acclimatization, the initial phases of the response involve receptor systems at the periphery and central receptors in the hypothalamus. Peripheral receptors include skin thermoreceptors and photoreceptors in the retina which drive autonomic and endocrine responses to the changing environment.

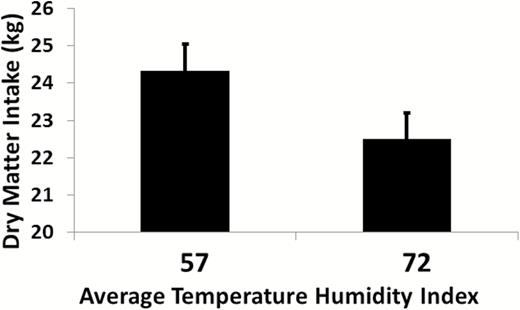

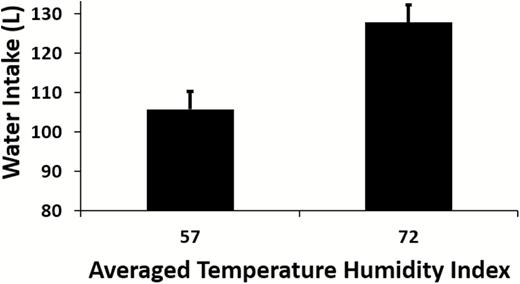

The stress response is divided into two phases, acute and chronic (Collier and Gebremedhin, 2015). These two stages correspond to the two stages of acclimatization to a stress. Acute stress responses last from a few minutes to a few days (Horowitz, 2002). Activation of the acute response to stress is initiated by thermal receptors located in the skin and hypothalamus which respond to changes in the environment (Collier and Gebremedhin, 2015; Figure 1). The afferent pathways for the stress transmit this information to the central nervous system including the thalamus and hypothalamus where setpoints are controlled and to the cortex for perception (Figure 1). These centers then activate various efferent pathways to induce a response to the environment, Figure 1. The acute response is driven by the autonomic nervous system promoting release of catecholamines and glucocorticoids which alter metabolism and activate transcription factors involved in the acute response. The severity of the acute stress response is affected by several factors including level of production, disease, age, body condition, and hair coat characteristics. The effect of acute heat stress on dairy cow feed intake is shown in Figure 2, which demonstrates a decrease in feed intake as the thermal environment increased from a temperature humidity index (THI) of 57–72.

Effect of thermoneutral (average THI = 57) or heat stress (average THI = 72) conditions on feed intake in lactating dairy cows under controlled environmental conditions (N = 95, feed intake decreased 11.5%, P < 0.001). Data summarized from Wheelock et al. (2010); Zimbelman et al. (2010); Hall et al. (2016, 2018).

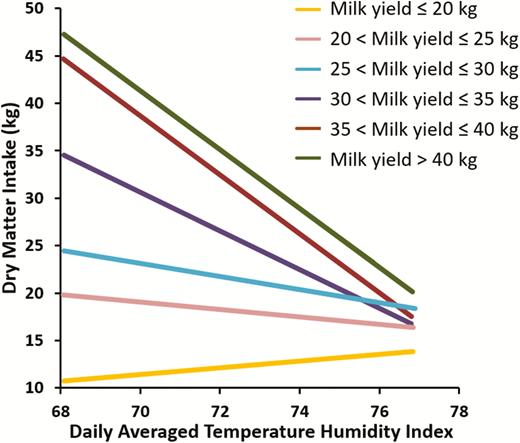

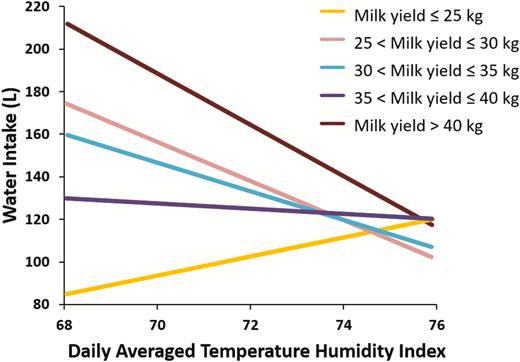

However, if you examine the relationship between production level and thermal stress you see a different pattern. As shown in Figure 3, the higher the milk yield at the onset of acute thermal stress the greater the decrease in feed intake in lactating dairy cows. At low levels of milk yield (e.g., below 25 kg of milk per day), there is little impact of heat stress on feed intake. Furthermore, the strength of the negative correlation between thermal environment and feed intake increases as daily milk yield increases as shown in Figure 3. The accelerated decline in intake of high producing animals is dictated by the need to rapidly decrease heat production to balance thermal load. This clearly demonstrates that high producing dairy cows are most susceptible to acute thermal loads.

Effect of level of milk production on feed intake response to acute (3 days) heat stress. Data summarized from Wheelock et al. (2010); Zimbelman et al. (2010); Hall et al. (2016, 2018).

Water intake requirements are increased in thermal stress to accommodate increased evaporative heat loss requirements. This pattern is shown in Figure 4 which depicts a 21% increase in water intake in lactating dairy cows as the thermal environment increased from a THI of 57 (thermoneutral) to a THI of 72 (heat stress).

Effect of chronic (10 days) thermoneutral (THI = 57) or heat stress (THI = 72) conditions on water intake in lactating dairy cows under controlled environmental conditions,(N = 77, 20.8% increase, P < 0.001). Data summarized from Wheelock et al. (2010); Zimbelman et al. (2010); Hall et al. (2016, 2018).

However, if we also examine the level of milk yield at the onset of acute heat stress we see a different pattern. As shown in Figure 5, at high levels of milk yield (>30 kg milk per day) water intake decreases to acute thermal load as water requirements for milk synthesis are decreased to decrease heat production of lactation. At lower levels of milk yield the water intake does indeed increase in order to meet increased water requirements for heat loss. Thus, acute heat stress drives down milk yield by multiple mechanisms which include rapid decreases in feed and water intake in conjunction with reduced milk synthesis. The local factors regulating reduced milk synthesis have not yet been elucidated.

Effect of level of milk production on water intake response to acute heat stress conditions. Data summarized from Wheelock et al. (2010); Zimbelman et al. (2010); Hall et al. (2016, 2018).

Acclimation, Acclimatization, and Adaptation

Animals have developed coping mechanisms to minimize the impact of these environmental stressors on their biological systems. These responses are termed acclimation, acclimatization, and adaptation. Acclimation is defined as the coordinated phenotypic response developed by the animal to a specific stressor in the environment (Fregley, 1996) while acclimatization refers to a coordinated response to several simultaneous stressors (e.g., temperature, humidity, and photoperiod; Bligh, 1976). Adaptation involves genetic changes as adverse environments persist over several generations of a species. Generally, there is hardly ever an example under normal environmental conditions where only one variable is changing. Therefore, typically an animal is undergoing acclimatization to a changing environment. Acclimation and acclimatization are induced by the environment and are considered phenotypic and not genotypic change and the responses decay if the stress is removed. Acclimation and acclimatization act to improve animal fitness to the environment. In many cases, the response is induced by sudden environmental change, such as heat or cold stress. In other examples, the acclimation response is driven by slower seasonal changes in photoperiod or other environmental cues such as the lunar cycle which permit the animal to “anticipate” the coming change in the environment leading to seasonal acclimation adjustments in insulation (coat thickness, fat deposition), feed intake, or reproductive activity in advance of the actual environmental change. However, in every case, the process is driven by the endocrine system and is “homeorhetic”; meaning metabolism is coordinated to support a specific physiologic state (Bauman and Currie, 1980). In this case, the specific physiologic state is the “acclimatized animal.” If the environmental stressors are present for prolonged periods of time (e.g., years) these metabolic and physiologic adjustments can become “fixed genetically” and the animal is considered “adapted” to the environment.

Acclimation and acclimatization are therefore not processes which involve evolutionary adaptations or natural selection, which are defined as changes allowing for preferential selection of an animal’s phenotype and are based on a genetic component passed to the next generation. The altered phenotype of acclimatized animals will return to the prior state if environmental stressors are removed, which is not true for animals which are genetically adapted to their environment (Collier et al., 2006). Acclimatization is a process that takes several days to weeks to occur, and close examination of this process reveals that it occurs via homeorhetic and not homeostatic mechanisms. As described by Bligh (1976), there are three functional differences between acclimatization responses and homeostatic or “reflex responses.” First, the acclimatization response takes much longer to occur (days or weeks vs. seconds or minutes). Second, the acclimatization responses generally have a hormonal link in the pathway from the central nervous system to the effector cell. Third, the acclimatization effect usually alters the ability of an effector cell or organ to respond to environmental change. These acclimatization responses are characteristic of homeorhetic mechanisms as described by Bauman and Currie (1980) and the net effect is to coordinate metabolism to achieve a new physiological state. Thus, the seasonally acclimatized animal is different metabolically in winter than in summer. Bauman and Currie (1980) incorporated these characteristics of acclimatization into the concept of homeorhesis, which is defined as “orchestrated changes for priorities of a physiological state” (Bauman and Currie, 1980). The concept originated from considering how physiological processes are regulated during pregnancy and lactation (Bauman and Currie, 1980), but application of the general concept has been extended to include different physiological states, nutritional and environmental situations, and even pathological conditions. Key features of homeorhetic controls are its chronic nature, hours and days vs. seconds and minutes required for most examples of homeostatic regulation; its simultaneous influence on multiple tissues and systems that results in an overall coordinated response, which is mediated through altered responses to homeostatic signals (Bauman and Elliot, 1983).

Acclimatization is generally considered to occur in two stages; acute or short term and chronic or long term (Horowitz, 2002). The acute phase involves the heat shock response at the cellular level (Carper et al., 1987) and homeostatic endocrine, physiological, and metabolic responses at the systemic level while the chronic or long-term phase results in acclimatization to the stressors sometimes called “conditioning” and involves reprogramming of gene expression and metabolism (Horowitz, 2002; Collier et al., 2006). In domestic animals, there is generally a loss in production as animals enter the acute phase and some or even all this productivity is restored as animals undergo acclimatization to the stressors.

The chronic response or stage 2 of acclimatization to stress is driven by continued exposure of the animal to the stressor. It is mediated by the endocrine system and is associated with altered receptor populations which change tissue sensitivity to homeostatic signals resulting in a new physiologic state (Bligh, 1976; Bauman and Currie, 1980). Thus, acute heat stress is a homeostatic response driven by the autonomic nervous system and chronic stress responses, acclimatization and seasonal changes are driven by the endocrine system and homeorhetic mechanisms.

Thermal Tolerance

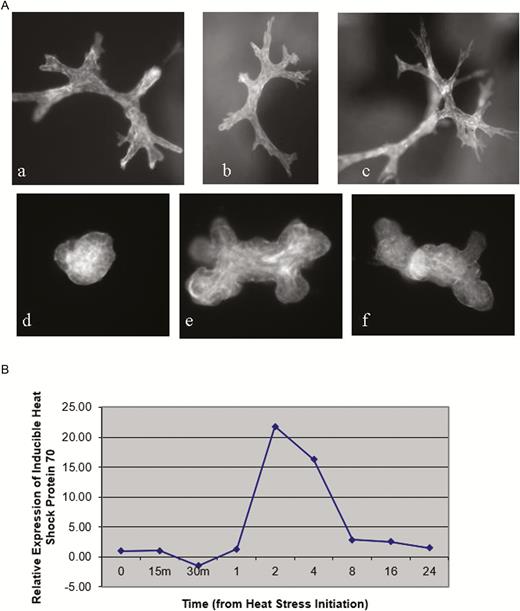

The degree to which animals can acclimatize to thermal environmental conditions is referred to as thermal plasticity. The thermal plasticity is affected by age, body size, disease, degree of insulation, and production level. High producing animals have reduced plasticity to environmental heat stress but increased plasticity to cold stress. The upper limit of the ability to adjust to thermal loads is referred to as thermal tolerance. The same factors which influence thermal plasticity also influence thermal tolerance when considering whole animals. At the cellular level, thermal tolerance is identified by the ability of an individual cell to maintain the production of heat shock proteins which protect against high temperature. As shown in Figure 6A, top row, when bovine mammary epithelial cells were cultured in a collagen matrix for 7 days at thermoneutral temperature (37 °C) they grew into ductal trees. When a subgroup was then subjected to heat shock (42 °C) and samples taken at regular intervals for analysis of inducible heat shock protein 70 (HSP-70) it was clear that the synthesis of inducible HSP 70 is increased in thermal stress for approximately 4 h but then rapidly declines (Figure 6B). This loss in ability to synthesize HSP 70 was associated with the complete collapse of the cytoskeleton at 24 h (Figure 6A, bottom row). Thus, thermotolerance of bovine mammary epithelial cells at 42 °C only lasted 4 h. The results of heat shock on bovine mammary epithelial cells in culture have previously been demonstrated in bovine embryos by Hansen and coworkers (Edwards and Hansen, 1997) who have demonstrated why bovine embryos are very susceptible to thermal shock.

(A) Phalloidin stained whole mounts of bovine mammary collagen gel cultures on day 7 of culture after 24 h at either 37 °C (top) or 42 °C (bottom), (B) Relative expression of inducible HSP-70 gene RNA in response to acute thermal stress. From Collier et al. (2006).

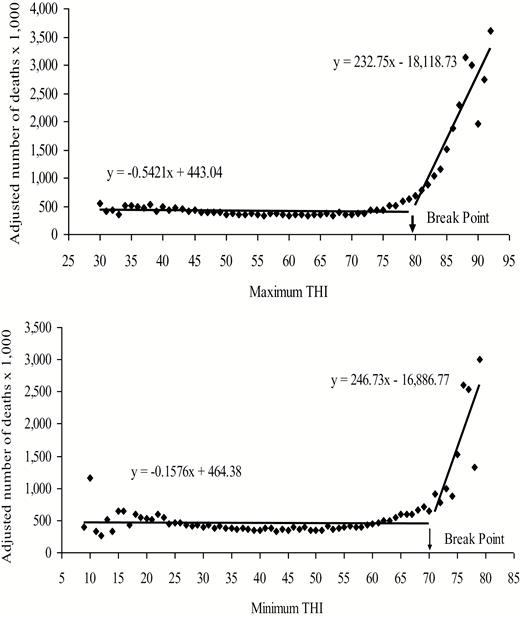

The best available data on thermal tolerance of dairy cattle was published by Vitali et al. (2009) who examined the mortality records of 320,120 Italian Holstein cows over a 6-year period. They reported that seasonal patterns in mortality were identified in all 6 years. Furthermore, they demonstrated a clear relationship between THI and death rate for both maximum and minimum daily THI as shown in Figure 7.

Adjusted number of deaths in relation to maximum (A) and minimum (B) THI; (A) a break point was detected at 79.6 THI. Below the break point, the adjusted number of deaths was constant across THI values (R2 = 0.0119, F1,50 = 0.910, P = 0.5), whereas above 79.6 THI, the adjusted number of deaths rose sharply with THI (R2 = 0.8382, F1,13 = 269.65 P ≤ 0.001); (B) a break point was detected at 70.3 THI. Below the break point, the adjusted number of deaths was constant across THI values (R2 = 0.0004, F1,62 = 0.930, P = 0.5), whereas above 70.3 THI, the adjusted number of deaths rose sharply with THI (R2 = 0.6151, F1,9 = 707.01, P < 0.001). From Vitali et al. (2009).

These investigators reported that a daily afternoon maximum THI of 87 and a minimum morning THI of 77 should be considered the upper and lower daily THI values for maximum risk of death of dairy cows to heat stress (Vitali et al. 2009). It is quite possible that as we increase average milk yield per cow these critical temperature thresholds will decrease.

As pointed out by several investigators, the separate evolution of Bos taurus, Bos indicus, and Sanga cattle has resulted in Bos indicus and Sanga cattle developing genotypes that confer improved thermal tolerance compared with Bos taurus cattle in both beef and dairy populations (Kadzere et al., 2002; Hansen, 2004). Detection of large genotype × environment interactions in dairy cattle for milk yield (Ravagnolo et al., 2000; Bohmanova et al., 2008) in just the Holstein cattle population, indicates that there is considerable opportunity to improve thermal resistance and performance in dairy cattle. These differences include thermoregulatory capability, feed intake and production responses, and cellular differences in heat shock responses (Hansen, 2004; Collier et al., 2006). Studying the relationship between genotype and thermal tolerance offers opportunities for engineering animals that are more resistant to climatic stressors.

Conclusion

A variety of environmental factors such as ambient temperature, solar radiation, relative humidity, and wind speed are known to have direct and indirect effects on domestic animals. The direct effects involve impacts of the environment on thermoregulation, the endocrine system, metabolism, production, and reproduction. Indirect effects include impacts of the environment on food and water availability, pest and pathogen populations, and resistance of the immune system to immunologic challenge. Animals have developed coping mechanisms to minimize the impact of these environmental stressors on their biological systems. These responses are broadly described as acclimation, acclimatization, and adaptation. Acclimation is the coordinated phenotypic response developed by the animal to a specific stressor in the environment while acclimatization refers to the coordinated response to several individual stressors simultaneously (e.g., temperature, humidity, and photoperiod). In general, there is hardly ever a case in the natural environment where only one environmental variable changes. Thus, in most cases the animal is undergoing acclimatization to the changing environment. Acclimation and acclimatization involve phenotypic and not genotypic change, and the acclimation responses will decay if the stress is removed. The overall impact of acclimation and acclimatization is to improve the fitness of the animal in the environment. In many cases, the acclimation response is induced by sudden environmental change. In other examples, the acclimation response is driven by changes in photoperiod or other environmental cues such as day length, which permit the animal to “anticipate” the coming change in the environment leading to seasonal acclimation adjustments in insulation (coat thickness, fat deposition), feed intake, or reproductive activity in advance of the actual environmental change. However, in every case, the process is driven by the endocrine system which coordinates metabolism to support a new physiological state, the acclimatized animal.

Acclimatization to a stressor is a two-stage process. The first stage is driven by homeostatic responses to environmental change and the second stage is a homeorhetic process driven by the endocrine system which enables animals to respond to a stress. The resulting cellular, metabolic, and systemic changes associated with acclimatization is to reduce the impact of the stress on the animal and allow it to function more effectively in the stressful environment. These changes are lost if the stress is removed so the process is not based on changes in the genome. However, if the stressful environment is not removed over successive generations these changes will become “genetically fixed” and are referred to as adaptations. A better understanding of genetic differences between adapted animals will contribute useful information on the genes associated with acclimation. Likewise, study of gene expression changes during acclimatization will assist in identifying genes associated with improved thermotolerance.

About the Authors

Robert J. Collier received his PhD from the University of Illinois and is currently Emeritus Professor of Environmental Physiology in the School of Animal and Comparative Biomedical Sciences, University of Arizona.

Lance Baumgard received his PhD from Cornell University. He joined the faculty in the Department of Animal Science at the University of Arizona in 2001 and in 2009, he became the Norman Jacobson Professor of Nutritional Physiology at Iowa State University.

Rosemarie Burgos Zimbelman received her PhD from the Department of Animal Science at the University of Arizona. She is currently Head of Nutrition at Dairy Nutrition Services, Chief Operating Officer of Animal Nutrition systems, Vice-President of Tarome, Inc and Partner at Rio Blanco Dairy, Chandler, AZ.

Yao Xiao received his PhD at Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China. He is currently a postdoctoral trainee in the laboratory of Dr. Peter Hansen, Department of Animal Sciences, University of Florida.

Literature Cited