Cases From AHRQ WebM&M: Rapid Mis-St(r)ep

processing....

The Commentary

This 5-year-old with a sore throat illustrates an issue faced millions of times in the United States each year. Streptococcal pharyngitis/tonsillitis is among the most common illnesses seen by primary care providers. The importance of this infection is evidenced by the many guidelines published by professional societies not only in the United States, but around the world.[1-3] Despite this attention and a far greater understanding of the microbiology and epidemiology of group A streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes), there has been essentially no "translation" (to use the current buzzword) of the results of laboratory research to everyday clinical management of streptococcal pharyngitis during the past half-century. Parents still bring their children with a sore throat to the clinician for a throat swab and are often given an antibiotic indiscriminately (most often a penicillin). Essentially no change in management has occurred!

The clinical diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis is frequently difficult, in part because patients don't always present with classic signs and symptoms.[4,5] Moreover, presenting symptoms vary with the age of the patient.[4] For example, this 5-year-old had the classic clinical presentation for school-age children, who tend to present with anterior cervical lymphadenitis (tender lymph nodes) and abdominal pain. Further adding to the management challenge, many patients with a viral upper respiratory tract infection will also be concomitant carriers of group A streptococci.[5] Given these factors, published clinical algorithms are often imperfect in making the diagnosis and guiding appropriate therapy.

As patients usually improve symptomatically even without antibiotic therapy, the goal of antibiotic therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis is eradication of the organism from the throat. Eradication is necessary to prevent nonsuppurative sequelae such as rheumatic fever in infected individuals.

Although the amoxicillin given to this child is identical or similar to that recommended by most clinical guidelines, therapy can be problematic. While there has never been a group A streptococcal clinical isolate that has shown resistance to penicillin(s),[7] penicillin's bitter taste is such that children do not like to ingest it, leading many clinicians to prefer the more palatable amoxicillin suspension. Recent support by some for short-course antibiotic therapy (fewer than 10 full days of a penicillin or cephalosporin, macrolide, or azalide) remains controversial and has not been included in most current guidelines in the United States. At the present time, a full 10-day course of most antibiotics is recommended in most authoritative guidelines.[1-3]

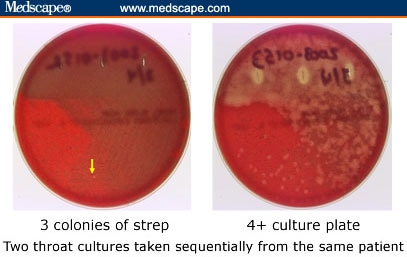

Perhaps a practical, clinically adaptable advance in management of group A streptococcal infection of the throat is RADTs for group A streptococci. One problem with RADTs is illustrated by the patient presented here. Studies during the past 20 years indicate that the specificity (i.e., the ability of a positive test to detect the presence of group A streptococci) of these tests is much better than the sensitivity (the ability of a negative test to exclude the presence of group A streptococci). That is, if the rapid strep test is positive, the patient likely has a group A streptococcal infection, but a negative test does not rule out the infection. Since essentially all rapid streptococcal tests are based upon an antigen-antibody reaction involving the group-specific carbohydrate of the cell wall, a sufficient number of organisms must be present on the swab in order to result in a "positive" test. This means that insufficiently thorough swabbing of the pharynx/tonsils and/or a relatively low organism load in the throat can result in falsely negative results. Sampling error (see Figure 1) is one key reason why authoritative sources and major guidelines recommend that if a rapid test is negative, a concomitant culture should be carried out.

Figure 1. Example of Sampling Error in Throat Cultures. Two swabs were taken from the same child within 20 seconds and immediately plated onto appropriate agar. One swab (right) resulted in a strongly positive plate, while the other (left) led to only three colonies on the plate [in the photo, only one can be seen clearly (arrow)]. This weakly positive culture almost certainly would have resulted in a negative rapid antigen detection test, yet the organisms can be detected on the culture plate. (Slide by Edward L. Kaplan, MD; 2003.)

False-positive throat RADTs also occur, but these are much less common. One documented cause for a falsely positive rapid test is related to the fact that some strains of Streptococcus milleri, a common part of the oral flora, carry the group A carbohydrate antigen on their surface and thus react positively with the usual commercially available RADT for Streptococcus pyogenes.[8] These false positives are rare and should not affect clinical management. A positive RADT should result in antibiotic therapy for patients with consistent signs and symptoms. Some clinical microbiology laboratories may overlook or incorrectly identify the presence of group A streptococci on agar plates; this possibility is recognized.[9]

In this case, the physician was concerned about the possibility of streptococcal pharyngitis. There are only two aspects of the medical care that one might question. The presence of tender anterior cervical lymph nodes is a very important clinical finding and has been correlated with true streptococcal infection.[5] This should have emphasized the need for a back-up agar plate culture. When one suspects streptococcal infection, a strep culture should be sent even when the RADT is negative. In retrospect, the initial rapid test may have been negative due to a sampling issue. The sample obtained on the swab may not have been sufficiently representative to trap an adequate number of streptococci to allow the rapid test to disclose their presence. When swabbing the tonsils and posterior pharynx, care should be taken to avoid the tongue. The swab is then moved back and forth across the posterior pharynx, tonsils, or tonsillar fossae. The physician appropriately advised the parent to return if the child's symptoms worsened.

The presented case illustrates several clinical and laboratory issues that remain controversial and result in variation in the medical management of streptococcal tonsillitis and pharyngitis. In the future, a cost-effective streptococcal vaccine may become available to assist in the control of this infection and its sequelae. Until then, more "translational" research is needed to improve both the medical care of patients with streptococcal tonsillitis/pharyngitis and the public health approaches to this common infection and its sequelae.