If someone traveling the Sahara Desert with you said, “I bet there used to be a huge river right about… here,” you would probably think it's time to stop for food and water. But that’s exactly what some scientists have said, and it turns out they were right.

Obviously, that implies the arid Sahara hasn’t always been quite so arid. We don’t even have to reach back far into the murky depths of geologic time in this case. The cycles in Earth’s orbit include a wobbling top motion called precession that alters the extremity of summer and winter over a period of about 23,000 years. When the summer sun is stronger over northern Africa, the equatorial boundary in Earth’s atmospheric circulation is pushed to the north—and life-giving rain comes with it.

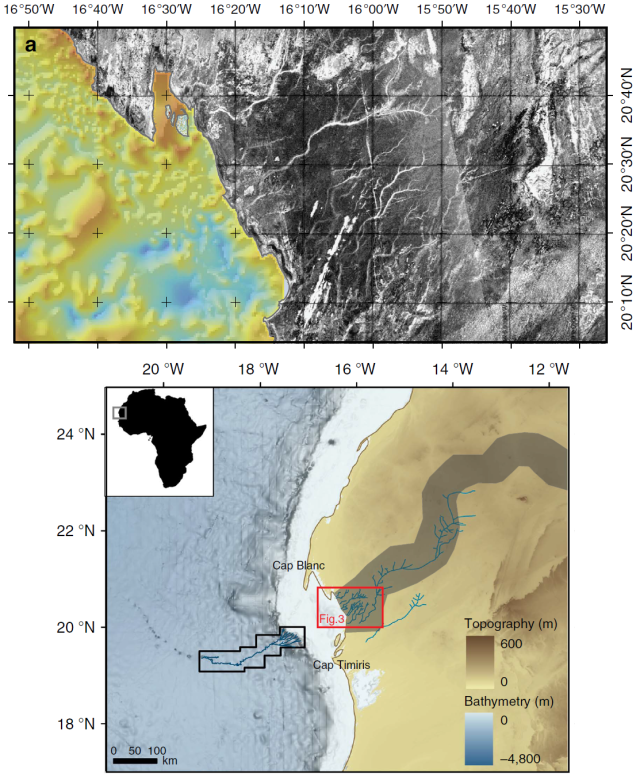

It was actually seafloor sediments that proved this to us. Beyond the mouth of the Nile River, layers of sediment rich in organic material testify to periods of bigger flows. And off the coast of Mauritania to the west, there are also layers of river sediment—and no river. What’s more, surveys of the seafloor along Mauritania’s coastline discovered a large submarine canyon similar to those connected with major rivers elsewhere.

Adding to this wild-seeming story, researchers analyzing topography for major river valleys found a pretty normal looking route for one through the Sahara. But how do you look for evidence of that river on land? The shifting sand dunes of the Sahara can quickly heal over the wounds gouged by a river.

Unless you’re prepared to drill many thousands of holes in the desert to search for a bedrock valley, the answer is X-ray glasses, of course. Or, rather, microwave radar aboard Japan’s Advanced Land Observing Satellite. That sensor has the convenient ability to see through a couple meters of dry sand, revealing obscured features.

And wouldn’t you know it, the satellite data showed a team, led by the French Research Institute for Exploitation of the Sea’s Charlotte Skonieczny, river valleys right where they ought to be. Channels extended inland from the submarine canyon in Arguin Bay, falling right along the path predicted by the topographic analysis. The researchers were able to follow the main valley for a little over 500 kilometers to the northeast before the sands grew too thick for the satellite’s signal to penetrate.

To be fair, there are a few spots where channels are actually visible in satellite images because they aren’t completely buried, but the mapped system of valleys extends far beyond these teasers. As recently as 5,000 years ago, monsoon rains turned the Sahara Desert into more of a Sahara savannah, and this river valley—called the Tamanrasset—swelled with water bound for the Atlantic Ocean. The Earth is a dynamic place.

Open Access at Nature Communications, 2015. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms9751 (About DOIs).

reader comments

32