The Lingering Trauma of Stasi Surveillance

Thirty years after reunification, memories of the East German police state continue to exact a profound psychological toll.

BERLIN—It has been 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, but this group-therapy session for victims of the East German dictatorship still meets every two weeks. Seated at the table in a cozy room off a peaceful cobbled street is a tall, sturdily built man who wears a thick gold chain and heavy boots. It was his penchant for edgy dressing that first got him in trouble with the secret police: He refused to cut his hair and wear a government-approved scarf to school exams. To his left is a woman who also protested the state-administered school uniform. Opposite is a man who made the mistake of applying to leave the country.

Having become enemies of the state, they were all punished in various ways and spent time in prison. And they were all made aware that they were watched at all times.

These three were among millions of citizens of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), a state that, until its collapse a year after the wall came down, went to extraordinary lengths to spy on and control its citizens. The Ministry for State Security—commonly known as the Stasi—wiretapped, bugged, and tracked citizens. It steamed open letters and drilled holes in walls. It had nearly 200,000 unofficial informers and hundreds of thousands more occasional sources providing information on their friends, neighbors, relatives, and colleagues. As the self-declared sword and shield regime, it aimed not merely to stamp out dissent, but to support a far-reaching propaganda machine in creating a new, perfect communist human being.

It was an unashamed police state, one in which extreme measures, even by authoritarian standards, were taken to curtail freedoms, until it finally fell and was subsumed into a newly reunified Germany. Yet the impact of the GDR’s measures did not end then. Indeed, that impact continues to be felt today. And if its efforts serve as an example to modern surveillance states—China, North Korea, Belarus, and Uzbekistan among them—its legacy serves as a warning, an insight into how such vast systems of control can affect our minds and societies.

All over the world, authoritarian regimes still use some of the tactics favored by the East German dictatorship—informers are still widely used, for instance. But states are now using modern technology to oppress their citizens in ways simply unavailable to the Stasi—by monitoring movements, spying on communications, and tracking financial transactions, to name just a few. The tools, in fact, are available to (and used by) companies and the governments of liberal democracies, too. “States now have far more power than the Stasi,” David Murakami Wood, a surveillance sociologist and an associate professor at Queen’s University in Canada, says. “And it’s not just states we have to worry about now.”

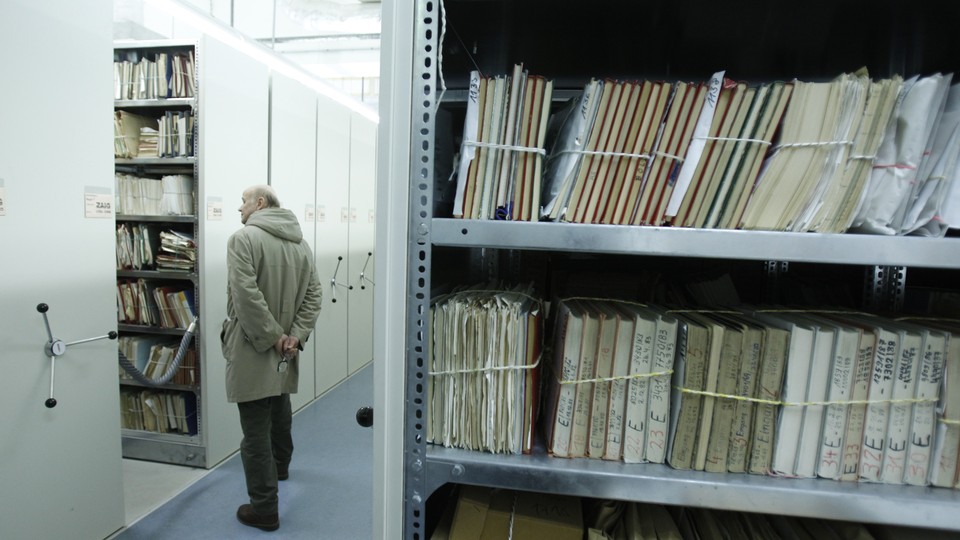

Without this contemporary technology, Stasi monitoring hinged on files. Then a central part and now an enduring symbol of their surveillance system, they are innumerable: If you were to lay them end to end, they would stretch 111 kilometers. This year, I visited one of the buildings where they are kept. A bright light flooded the room, and steel cabinets were slid open to expose orange-brown files piled to a dizzying height. There was a chair in case I felt sick. Though the room was kept cool to preserve the paper, I felt my temperature rise.

While many former victims of the Stasi ask for their own files, requests to view them often also come from the second and third generations, too, a spokeswoman for the Stasi Records Agency had told me, and that was true in my case. My grandmother fled the GDR in 1958—after dressing as if she were going to work, she boarded a train and did not stop traveling until she reached London. The Berlin Wall was built a few years later; she would not see her family again until after it fell, by which time she had married, divorced, and become a mother and grandmother. It wasn’t until after she died that I reflected on the guarded way she interacted with people: She lived an isolated life and, despite spending her whole adult life in Britain, had hardly any friends. Only eight people attended her funeral. She never talked about her experiences in the GDR or engaged in critical political discussion.

Celia Fisher, a psychologist, told me there could have been lots of reasons for this, including trauma and survivor guilt. Moreover, the experiences of East Germans during the 40-year dictatorship were diverse. In fact, some even look back on their experiences fondly, according to Ulrike Neuendorf, a social anthropologist who has researched the psychosocial legacy of surveillance in the GDR.

But many others suffered greatly—particularly those who were targeted by the Stasi. Stefan Trobisch-Lütge has focused his psychiatric career on helping these people, who, he says, suffer from a variety of problems, including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression.

At Trobisch-Lütge’s practice here in Berlin, where haunting paintings of barbed wire and ghostlike figures line the walls, Chris Hendschke, a member of the group-counseling session, rhetorically asks the woman sitting next to him, “Friends? Do I still have friends?” He is smiling, but the truth is, he says, life in the GDR harmed his ability to trust and form lasting relationships.

In the mid-1980s, Hendschke’s life changed when he submitted an application to leave the country. That angered the Stasi, who threatened to force his wife out of her tailoring job. After a year waiting for the outcome of his application, he marched to complain at the office of human rights. The Stasi were, however, waiting for him; his intentions had been betrayed in advance. “By whom?” he says, “Who knows. Everyone knew everything about everyone else.” He was thrown in jail, and released a year and a half later in a prisoner exchange with West Germany.

The rest of the group agreed that the destruction of trust was one of the most painful legacies of their experiences in the GDR. The dense informer network meant that everyone spied on one another. Many did not find out who had informed on them until decades later, when they requested their Stasi file. One woman spoke of how she was devastated when she discovered that the man she loved was informing on her. Still reeling from this betrayal, she later found out another close friend was also spying on her. A man at the session recounted how his intention to leave the country was betrayed, and so instead of getting out, he was thrown in jail. Ten years later, on receiving his Stasi file, he found out that the person who betrayed him was his girlfriend.

“I trust only a few people I have known a long time,” Hendschke told me. “I only get to know new people with a certain distance. My life today is pretty isolated.”

Those at the group therapy session said that beyond these betrayals, the general atmosphere of the GDR meant they had to be constantly on their guard. There is evidence that this affected the whole of East German society: A 2015 study concluded that the detrimental impact of government surveillance persists and has led to lower levels of trust in post-reunification Germany. This is one of the most pernicious psychological effects of surveillance in other contexts, too, says Fisher, the psychologist.

The perception that the Stasi was all-knowing also led to self-censorship. For some, even though the dictatorship has been over for 30 years, the caution lingers—one woman at the session said she shares her political views only with people she knows well. People were socialized in a system where they had to think twice before voicing their true opinions. The fear that information can be used against you, now or in the future, can stay with you your whole life, says Neuendorf. This fear was particularly pronounced in the GDR, where the Stasi used the data it had on targets to tailor-make ways to break them and their relationships down, a process known as Zersetzung.

Scott Thompson, a surveillance historian at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, says repression of identity and, by extension, culture is common in heavily monitored societies across the world, from bans on rap music and tattoos in China to the stamping out of almost all individuality in North Korea. Self-expression of any kind was near-impossible in East Germany. This loss, to both the individual and the broader culture, can last decades, Thompson told me. In Germany, there is another impact: None of the members of the group session, for example, have a Facebook account, which is not unusual in a country with lower than typical social-media usage. Certainly it is no coincidence that Germany has some of the strongest privacy laws in the world and a palpable cultural aversion to surveillance, and appears as a rare blank spot in Google Street View’s coverage of Europe.

How surveillance affects a society will, of course, depend on the extent to which it is rolled out and the rights of individual citizens in relation to the state—there are strong arguments to be made in favor of surveillance, for example, to promote safety even in free societies. And though it is simplistic to draw a line between democratic and autocratic monitoring, the impact of monitoring, by corporations, governments, and (via social media) our peers, in liberal democracies is different than in states with narrow room for dissent. Ultimately all surveillance is control, whether it is to ensure you obey certain rules or buy things or vote for a particular party, says Thompson. And the lived experience of surveillance will vary according to affluence and race, says Fisher, who researched the impact of monitoring Muslims in the United States after 9/11.

I did not get to read my grandmother’s Stasi file—many are uncataloged, and finding it may take years (if it is ever found). But even without it, talking to people who lived through the dictatorship shed some light on her early life experiences and how they might have affected her.

Living under the Stasi was a collective experience, yet the traumas inflicted were deeply personal, ones the people I spoke with at the therapy session said they live with on their own. Still, many are making progress: As a tiny therapy dog skips across the floor, they all say they have found comfort with one another. Hendschke says while he will never be free of his painful emotions, he understands them better. The woman whose boyfriend turned out to be a Stasi informer says she will always have trust issues, but the sessions have helped a little—her current partner proposed to her seven times, until, on the eighth time, she said yes.