Button Salesman Discovers Most of Life on Earth: True Story

He looked. He gasped. What are these things? They're alive—and everywhere!

What if someone told you that right now there are trillions of fellow Earthlings hiding, crawling, and buzzing directly in front of you, under you, in you, on you—but you can’t see them.

And what if—indulge me here—all of a sudden, you could?

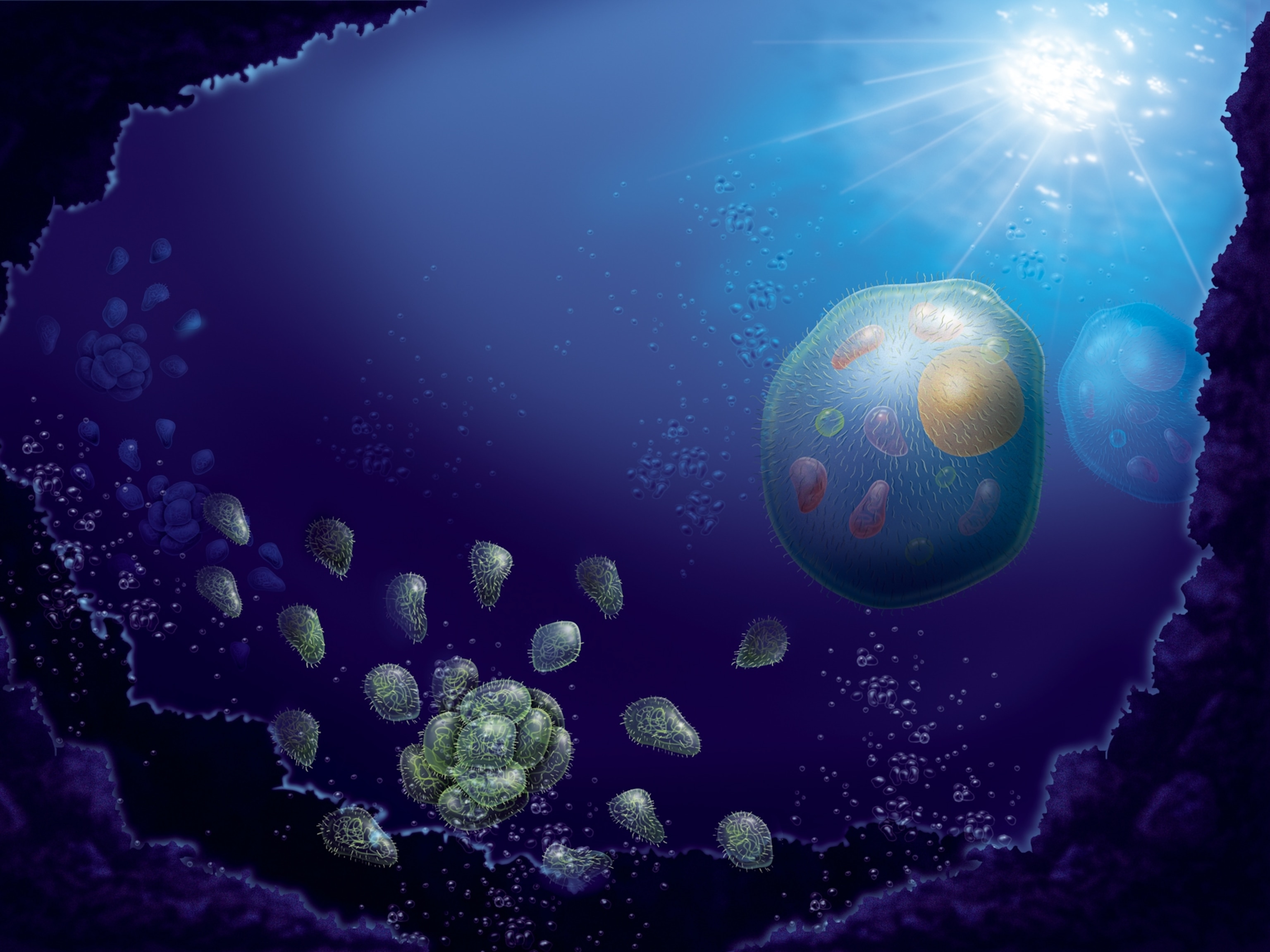

What if, popping into view in the strangest places, you could suddenly see moving, dancing, spinning creatures where you’d never seen them before? You look in a bucket of water—there they are. You look in a pond, in a puddle, on your skin, even at the plaque between your teeth, and they’re there too—in different shapes, with different moves, but uncannily, unmistakably alive. You don’t know what to call them, but you’re the first Earthling ever to see what the overwhelming majority of creatures on our planet look like, and for a little while, you’re the only one—the only one who could gaze down at the sweep of nature’s magnificence. What would that be like? Would you be frightened? Mystified? Joyous?

This actually happened. All at once, sometime in the early 1670s, one man took the first deep dive into our microbial world. He wasn’t a scholar, a philosopher, or a scientist. He ran a small fabric shop in Holland. He also sold ribbons and buttons. In his spare time, he got good at grinding lenses, so he made himself an eyeglass that could magnify 270 times. For its day, it was the best microscope in the world—ten times more powerful than any other. But most of all, and unlike most of his neighbors, he wanted to see; he was a deeply curious man. And that made all the difference.

According to my blog colleague Ed Yong, who describes this in his new book, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek didn’t go to college and didn’t speak Latin (the language of scholars), but when he looked through his microscope, he got giddy with astonishment. Right away, he wanted people to know that there was a vast community of “animalcules,” as he called them, everywhere.

So he sent his descriptions to the most prestigious scientific society of his day, the Royal Society in London. Apologizing for his crude language (“pray take not amiss my poor pen”), he told them what he’d seen, in one letter, then another, then another ...

In an ordinary drop of water, he wrote, he’d found “little eels, or worms, lying all huddled up together and wriggling … the whole water seemed to be alive with these multifarious animalcules.” (Hello, bacteria!)

Ewww. Was he disgusted? Horrified? This was rainwater, after all.

Not at all: “ ... I must say, for my part, that no more pleasant sight has ever come before my eye than these thousands of living creatures, seen all alive in a little drop of water ...”

A Miniature Horse-Headed Thingy

In another letter, he describes a roundish critter that “stuck out two little horns which were continuously moved, after the fashion of a horse’s ears [and with a body that ended in a tail].” (Hello, microbe we now call a protist!)

According to the science writer Leonard Mlodinow, who also tells van Leeuwenhoek’s story in his new book, when the Dutch shopkeeper’s letters were read to the society’s members, some were intrigued. Others scoffed. What does this Dutchman know, they said. They wanted to see for themselves.

Van Leeuwenhoek wouldn’t send them his microscopes; he was jealous of his craft. But he did send affidavits from a Dutch public notary, a barrister, and his local minister. Gradually, the invisible world he described began to find an audience.

Knock, Knock—It’s the Czar

One day in the spring of 1698, two foreign gentlemen knocked on his door and announced that the czar of Russia, Peter the Great, was at that very moment waiting on board his royal ship in the nearby River Schie, hoping to meet the shopkeeper. He would have come on his own, his servants said, but he worried that appearing on the streets of Delft might cause a commotion, so he asked van Leeuwenhoek to grab a couple of samples and join him on board. Van Leeuwenhoek took a live eel and a couple of microscopes and spent two hours with the czar gazing at blood rushing through the capillaries of the eel’s tail. His critics grew quiet. Van Leeuwenhoek was becoming famous.

Perhaps his most celebrated letter describes, as Yong puts it, “the white, batter-thick plaque lodged between his teeth.” Van Leeuwenhoek scraped some plaque out of his own mouth, took a look, and was gobsmacked. His teeth were covered, he found, with active creatures.

“ … there were many very little living animalcules, very prettily a-moving. The biggest sort … had a very strong and swift motion, and shot through the water (or spittle) like a pike does through the water. The second sort … oft-times spun round like a top … and these were far more in number.”

He also scraped plaque from two willing ladies (probably his wife and daughter) and from two old men who claimed never to have cleaned their teeth their whole lives. He then drew what he saw in those mouths—and you can see those drawings here:

In the older gentlemen, he found “an unbelievably great company of living animalcules, a-swimming more nimbly that any I had ever seen up to this time … [Their spittle] seemed to be alive.” These dental studies are among the first ever observations of living bacteria.

Most of what Van Leeuwenhoek saw had never been seen before. As science historian Douglas Anderson wrote, “Almost everything he saw he was the first human ever to see.”

The experience clearly thrilled him. His letters seem almost breathless with discovery—and with joy. But here and there, Yong found another theme: a brooding disappointment. He’d done all this on “impulse and curiosity alone,” he wrote the society. “[B]eside myself in our town there are no philosophers who practice this art … ” His neighbors, he felt, were more interested in making money or chasing success. “Not one man in a thousand is capable of such study, because it needs much time and spending much money.” His excitement, he noticed, didn’t sink in with the broader population. So the world is filled with teeny somethings, they’d say. So what?

The Wonder Question

Van Leeuwenhoek wondered about this out loud: “[O]ver and above all, most men are not curious to know; nay, some even make no bones about saying, What does it matter whether we know this or not?”

This mood surprises him—more than surprises; it seems to hurt. Me too. When I write these little essays, or go on the radio, when I come upon something I didn’t know, something that gives me that ohmygod feeling that pushes me to learn, to tell, to exclaim, and when I rush to a friend and gush it all out and am met by a patient pair of eyes asking, “Are we done here? Can we get back to lunch?” I feel, not just deflated, but mystified. What didn’t I say? What could I have said better? Why does wonder not excuse itself?

For whatever reason, Yong reports, van Leeuwenhoek’s discoveries, so exciting at first, gradually faded from public memory. Even scholars fell away from microscopic life, so by the 1730s, when the Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus decided to classify all life, he dumped all of van Leeuwenhoek’s very different animalcules into the phylum Vermes (for worms), genus Chaos (meaning formless). It’s as though what he’d seen went back to unseen. Wonder, it seems, was not enough.

Ed Yong’s book, I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life, is a tour of microbial life; he shows us where all those itsy-bitsy life-forms come from, how they hang out, how they thrive, how they hurt, how they help, how they are so intermingled inside and about us that we should begin to think of them and us as working units of life. If van Leeuwenhoek were alive, he’d be carrying a copy and doing a private happy dance. Leonard Mlodinow’s The Upright Thinkers: The Human Journey From Living in Trees to Understanding the Cosmos is, like most of his books, a funny, easygoing saunter through the ages, where we meet the people who asked the tough questions and feasted on wonder. This guy can’t stop telling great yarns. Both books are good reads.

The microbeman seen in this video was created by the world’s first museum devoted entirely to microbes. It’s in Amsterdam, and it’s called Micropia, and when you’re done looking at this, you should wander over to their site. Find out how many microbes you exchange whenever you kiss. It’s not yucky, it’s … wonderful.

Robert Krulwich is cohost of Radiolab, WNYC's Peabody Award–winning program about "big ideas" and now one of public radio’s most popular shows. It is carried on more than 500 radio stations, and its podcasts are downloaded over five million times each month. In Curiously Krulwich, Robert looks for "the little things that catch my eye—that when I lean in, get bigger, richer, and much more compelling." You can see more of his work at radiolab.com and follow him on Twitter @rkrulwich.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- Behind the scenes at America’s biggest birding festivalBehind the scenes at America’s biggest birding festival

- How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’

Environment

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

History & Culture

- This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?

- These were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ eraThese were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ era

Science

- Why dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a rewardWhy dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a reward

- What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?

- Oral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuriesOral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuries

- How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

- Science

How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out. - Does meditation actually work? Here’s what the science says.Does meditation actually work? Here’s what the science says.

Travel

- What to see and do in Werfen, Austria's iconic destinationWhat to see and do in Werfen, Austria's iconic destination

- How to get front-row seats to an active volcano in GuatemalaHow to get front-row seats to an active volcano in Guatemala

- Urban wine is making a comeback in Paris. Here's how to try itUrban wine is making a comeback in Paris. Here's how to try it

- Discover the sordid history behind these English country homesDiscover the sordid history behind these English country homes