Veterans Ron Kovic, Oliver Stone on the True Cost of War (Video & Transcript)

For Veterans Day, Truthdig presents footage of the author and the film director discussing their experiences with war, peace and politics in a discussion moderated by Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer.

Many Americans spend Veterans Day combing the internet for deals and discounts or hosting a backyard barbecue, rather than pausing to think about war and those we send to fight in it.

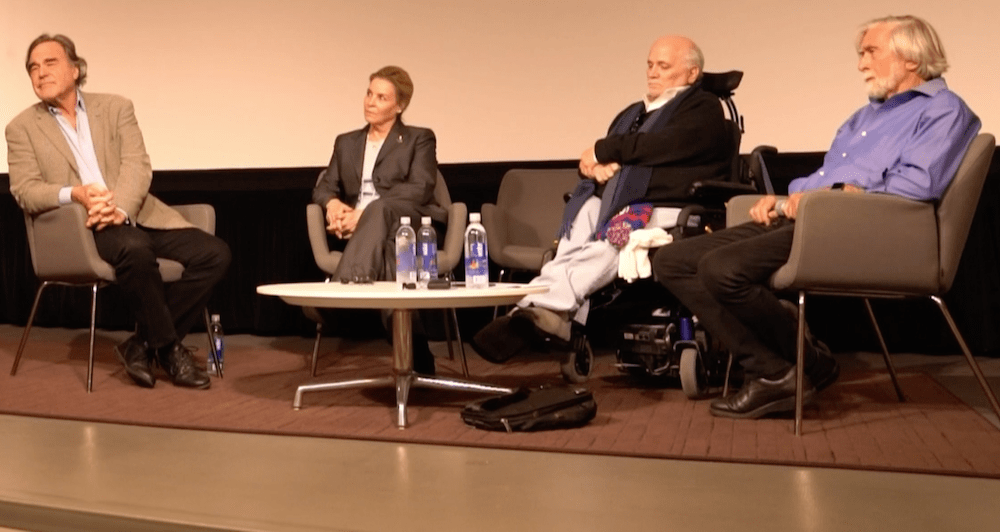

Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer recently hosted veterans Ron Kovic, an anti-war activist and author, and documentary filmmaker Oliver Stone at the University of Southern California for a discussion on war, peace and the American military-industrial complex. Kovic and Stone served in the Vietnam War, an experience that shaped their lives and their politics.

Stone and Kovic worked together on the film “Born on the Fourth of July,” based on Kovic’s autobiography of the same name. During their interview with Scheer, they discuss how the film came to be.

“For the rest of my life, I will thank him for changing my life, for making that movie,” Kovic says, gesturing to Stone.

Stone discusses the difficulties of creating a Hollywood film about the realities of war. “You have to realize that when it comes to war, killing people, shooting people, bombs, people dying, it’s a very political thing,” he says. “Every country gets wrapped up in its own sense of self, and its own flag, and these things are so distorted through time.”

The two share their views of patriotism and politics, from growing up under the shadow of World War II to today’s seemingly endless American military engagements abroad. The conversation concludes with a Q&A from the audience.

In honor of Veterans Day, Truthdig presents footage of the conversation, as well as links to past coverage of anti-war efforts of Kovic, Kevin Tillman, Tomas Young, Chris Hedges and Scheer. Check out the links below, and watch the full conversation between Scheer, Stone and Kovic (which also features Kovic’s partner, TerriAnn Ferren) in the player above. For a full transcript of the conversation above, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Ron Kovic, anti-war activist and author:

Click here to read Kovic’s essay “The Forgotten Wounded of Iraq.”

Click here to read an excerpt from the book “Hurricane Street.”

Click here to read Kovic’s essay “Reflections on the Vietnam War: The Things a Warrior Knows.”

Click here to read Kovic’s essay “In the Presence of My Enemy: A Reflection on War and Forgiveness.”

Click here to watch a conversation between Kovic, Chris Hedges and Robert Scheer.

Click here to see a photo essay of Kovic by Truthdig Publisher Zuade Kaufman.

Kevin Tillman, veteran and anti-war activist:

Click here to read Tillman’s heart-wrenching essay about his brother Pat, “After Pat’s Birthday.”

Chris Hedges, activist and Truthdig columnist, and Tomas Young, Iraq war veteran

Click here to read Young’s powerful plea to George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, “The Last Letter.”

Click here to read Hedges’ piece on Young, “The Last Days of Tomas Young.”

Click here to read Hedges’ interview with Young, “The Crucifixion of Tomas Young.”

Robert Scheer, Truthdig editor in chief:

Click here to read Scheer’s essay “Praise for Ron Kovic and His Legacy of Activism.”

Chris Hedges and Robert Scheer

Click here to watch Hedges and Scheer discuss war, religion and fighting American neoliberalism.

–Posted by Emma Niles

Full Transcript:

Ron Kovic: Well, Oliver and I met for the first time with Richard Boyle at the Sidewalk Cafe at Venice

Robert Scheer: This was after you wrote your book.

RK: Yeah, after I wrote my book.

RS: So why don’t you tell about writing your book?

RK: Well, I wrote the book, and I was living at the Santa Monica Bay Club, sleeping on a mattress on the floor. I had a $42 manual typewriter that I bought at Sears & Roebuck in Santa Monica. And with two fingers I wrote Born on the Fourth of July, the first draft in one month, three weeks and two days. And with that manuscript I flew to New York with a friend, we met with several publishers, and McGraw-Hill book company published the book. The book came out and was published on the front page, reviewed on the front page—there you go. Reviewed on the front page of the … Sunday Times Book Review, and got a good review. And then not long after, actually not long after the, I think it was August 15th, 1976, New York Times book review, Born on the Fourth of July, and then it received a second, also positive review the following day, Sunday and a Monday. And it was a few days later I received a call from my agent in New York City at the time, my literary agent Lynn Nesbit at International Creative Management, telling me that there was someone interested in taking out an option on, making the book into a movie. His name was Martin Bregman, Marty Bregman, who had produced … the movies Serpico and Dog Day Afternoon and several other movies. And he also worked closely with Al Pacino. And so Bregman and I—I went into New York City, met with Bregman, met with Pacino for the very first time. And they took out an option, and they hired a screenwriter, initially hired a screenwriter to write the adaptation of my book Born on the Fourth of July for the screen. And long story short … Al Pacino was not happy with it and Bregman wasn’t either. They did not accept it, and they were searching for another screenwriter. And there was another screenwriter that had just come from London, Oliver Stone, who was, who had just written, who had just adapted the Billy Hayes story, Midnight Express … the movie Midnight Express. And then he had come, I think he came back to New York, and one thing led to another; ran into a friend, if I’m not mistaken, and this friend told him that Bregman was looking for a screenwriter, and … from what I remember, he met with Bregman, and Bregman sent him out to the coast to meet with me. Oliver went out to the West Coast, and we met at the Sidewalk Cafe. And I was with Richard Boyle that day, who was later the, Richard and Oliver co-wrote … the movie Salvador together. But, Richard, who had been a longtime friend of mine. And so the three of us met that day. And actually, you know, I told this story once, quite a few times; when we met that day I remember telling Oliver, you know, there’s something about your name. It just sounds like a name that’s going to win the Academy Award. [Laughter] Really, it’s—Oliver Stone, it just sounded like it was going to be a very famous name someday. And a name that was going to win a lot of awards. Just, I don’t know, it had a real ring of destiny about it, that name. And so, yeah, that’s how we met. And then Oliver and I—then Marty sent him out to meet with me, and that’s where we met out there. And then we worked together for quite a while. I went back and forth between LA and New York, there were several different directors that came and went. And we got within a couple days of principal photography in New York, and the film fell apart. And Pacino left to do a movie with Norman Jewison called And Justice For All. And it broke our hearts, that; I remember being in an elevator in New York at Bregman’s building, saying to Oliver, Oliver telling me, “If I ever make it, if I ever make it in Hollywood, if I ever break through, I’m going to come back for you, Ronny, and I’m going to make Born on the Fourth of July.” So he made a promise that if he ever made it in Hollywood—because he was a struggling screenwriter at the time. Not that many people even knew the name Oliver Stone. Not that well known. And he was, you know, to go on to initially win the Academy Award, the Golden Globe for writing, what was it—writing, ah, it was Midnight Express, right? [5:00] The Midnight Express. And we were young back then, we were in our, we were in our late 20s, early 30s. … And we were both, both of us really were struggling to get our Vietnam stories out. And he had given me a copy of Platoon, and I remember reading the beginning of it, it was so powerful. It was overwhelmingly powerful, it was a devastating script. But nobody wanted to do it. And it looked like Fourth of July wasn’t going to get done, either. But then many years passed, he stayed in touch with me—every time I ran into Oliver in those years, before his big breakthrough with “Platoon,” every time I would run into him he would always bemoan the fact that we … hadn’t made Fourth of July yet. We’d come so close, and he kept reminding me that, you know, it should have happened. He had a chip on his shoulder about it, you know. And so then finally, finally, he did Salvador with the help of a couple of friends of mine, Richard Boyle and Dr. Rock. And it was a—I don’t know how it did at the box office, but it was a real critical success. And it was enough to interest funding for Platoon. So finally, he made Platoon, and … [i]t was a phenomenal success. I can still remember that time. It was everywhere; everybody was talking about it, everybody was going to see that movie. I remember seeing the … the initial screening of the movie. And it was just, it was one of the most powerful movies I had ever seen; it was just tremendous. And I had gone to quite a few of his screenings. I didn’t go to The Hand, but I went to I saw … Salvador, and quite a few of these early screenings. But Platoon was just, it was on a whole ’nother level, it was just tremendous. And it … won the Academy Award that year; it won just about everything, and it put him in a really great position. And not long after that, I received a call; he was in New York, and he was wrapping up the movie Wall Street. And I received a call–

RS: How many of you have seen Wall Street? You can learn more … watching that movie than getting a degree from this business school. [Laughter] That’s my comment.

RK: Yeah, just to make, to shorten it, I was asked to go to New York, my agent called me, he said that Oliver was going to call me. Then he—it was, it broke our hearts the first time that it fell through. And then the agent said he was going to call me, and then Oliver said, you know, we’re going to try again. So I flew to New York, we went out to Massapequa, and we scouted the town. And then I went back. And one thing led to another, you know. We met with, we met with different actors; we met with Charlie Sheen initially at an Italian restaurant in Santa Monica, I remember that. And … eventually we met with Sean Penn at Oliver’s house in Santa Monica at the time. And that didn’t work out for one reason or another. Then Tom Cruise. Tom Cruise, with the help of Tom and Oliver’s agent, Paula Wagner, right? Paula Wagner. We all came together that day, came down to my rented house in Redondo Beach, both these extraordinary men came to my house. And that was the beginning of the second attempt. And there were a couple of times when it didn’t look like it was gonna happen, but it finally did happen. And it changed my life. And it was extraordinary, what happened. He was tremendous on the set. I wish you could have been with me, I wish you could have seen him work on the set. He was the captain of the ship, you know; he had tremendous respect, all the people who worked with him respected him and worked with him. And … it was a great experience to be in Dallas, Texas, to be working on the story of my life, to be working with him, to see his promise come true, that dream come true. It meant the world to me. And for the rest of my life, I will thank him for changing my life, for making that movie, for sending out, you know, the greatest speech I could ever give about the reality of what war does to human beings, was because of that film that Oliver did. And I’ll always be grateful to you for that. Thank you. [10:00]

RS: So I think that also is a pretty good introduction to Oliver. Let me just say, Oliver was at Yale, growing up in a—father was a stockbroker, not going to give his whole history, but he was in George W. Bush’s class at Yale. And he can talk a little bit about it, but he left to join the Merchant Marines. He was in Vietnam, among other places, and then he ended up serving, he ended up being wounded, and Platoon is a story of his experience, in part. So why don’t you tell us about the making Born on the Fourth, and why Hollywood–let’s get to larger points here. How does Hollywood deal with war, that’s the subject; how does the media deal with war, and what has been your experience making three of, I would argue the three best movies made about war, at least in this country. I know that’s saying–actually, unfortunately that’s not saying so much. [Laughter] Too many good movies made about war. But one of them which we haven’t mentioned, Heaven and Earth, the third one in the trilogy, is actually the most ambitious, and in many ways the most important. Because no one has ever told about war from the point of view of the victims, the people, that are being bombed, that are being attacked, that are being heard about. And particularly from a female victim. And that’s what that movie attempts to do; it didn’t do as well commercially, but it’s critically a great success, and if you’ve never seen it, you got to go see it at some point. I want to teach a course just on Oliver Stone’s movies, and we can talk about all of them. And in the second half of this, after we take a break, I do—we began by, we showed President Trump’s speech talking about patriotism. And we also, we’re going to show a clip where he talks about—we haven’t shown those clips yet, we will show them, where in a speech today he talked about not only patriotism, he talked about going to war, he talked about Russia, the Second World War, and so forth. So I want to show a little bit from your series on the Cold War and so forth after the break. But why don’t we stick to Born on the Fourth now, and talk about how you came to make it, and the obstacles.

Oliver Stone: Yeah—quickly, but may I ask Ron a question? What was the date we met? You say at the Sidewalk Cafe—

RK: Yeah, it was July 3rd, 1977.

OS: Seven, that’s right, ’77.

RK: ’77, you, Richard, and myself, yeah.

OS: ’77, yeah.

RS: Do you have a mic?

OS: So I began working in September—

RS: You’re sitting on the mic.

OS: Oh. I began working in September, or roughly August, September, we began working together on the screenplay, right?

RK: Yeah.

OS: Yeah, Billy Friedkin was the director, and that was one of the reasons—you’re too young to know, but Billy Friedkin was the hottest director in Hollywood back in the 1970s. He’d done, a young man, French Connection and Exorcist back to back, which made big, big money. This was pre-[Steven] Spielberg and [George] Lucas. So he was, he was my film school idol, so to speak, and … to work with him was a big honor. It didn’t work out, as Ron said, and so forth; another director, and then cold feet from Al, and various things happened—

RK: And Dan Petrie, as well.

OS: Yeah, and that’s a sad story, nice man. But the German financing fell out. The problem, you saying to me, what is the obstacles for Hollywood and war films—and that is a very important point. … You have to realize that when it comes to war, killing people, shooting people, bombs, people dying—it’s a very political thing. … it’s very difficult to … unless you’re some Third World country, to really tell it like it is. Every country gets wrapped up in its own sense of self and its own flag, and these things are so distorted through time, and the more you see of war films, it’s really hard to get through. Even on Born on the Fourth of July, and certainly on Platoon, I know of patriotic issues that came up. And we had to thread the needle, in a sense. It’s a very—and when I did Heaven and Earth, which is a Vietnamese refugee story about a woman, it was impossible to—there was no interest at all to begin with. Now it’s different, but not that much—there was no interest in the Vietnamese side of the story. Certainly for the American side. And it was sad to see that movie die, because it cost a lot, and it was … actually the most expensive of the three. Tremendous amount of work we put into it. Backbreaking, creating villages and agriculture of Vietnam, and all the love and attention we devoted to it—it was sad to see that happen. Born was another tragedy, because Ron and I were heartbroken. I mean, he was chasing me down the boardwalk in Venice one night, trying to catch me—it’s pretty scary—because he was angry about the film, and he just was lashing out. And it was painful. To come back and do it turned out to be, it was Tom Cruise came in and made it financeable. Al Pacino had always been an issue; he was 38 years old when he was doing the original. I saw him rehearse, I saw the rehearsals with my own eyes; he was unbelievable, performance in a wheelchair. But it was theatrical; it belonged in a theater, 38, 39-year-old man playing a 21-year-old kid is not always the best thing. I think he’s a great actor, maybe he would have gotten away with it, but maybe in the end there was a reason for the delay. I never thought I would end up directing it, never in my wildest dreams. So anyway, it did happen, as Ron said. And we got rolling, and Cruise was a movie star; he’d just been in Top Gun, so he was the reigning star, sex symbol, young man. And here he was playing this role, and everybody was laughing, kind of saying you’re never going to pull this off, you’re just going with him for money because you can get it financed and, you know, he’s not an actor and so forth and so on. So it was demeaning, but Ron and I know that the guy worked like a dog. And he went to hang out for hours with Ron, going to department stores and sidewalks and seeing all the little problems of everyday life. He cared about detail, as he always does in his acting. And if you watch closely, he’s very impeccable on detail. Look at Rain Man as another example. And you’ll see a devoted person. And the film was not without its problems; it was very difficult to shoot in Dallas, in the medical ward there. It was just so graphic and realistic and depressing, the veterans hospital, which was the stand-in for the Bronx VA in Ron’s story. The parents, the homecoming, heartbreaking. Wonderful actors. We had problems with the ending; we had to do another ending, because the original didn’t work, and it was, Tom was pushing for the other ending. And I have to say, he was right. The ending ended up being a different ending, and the Democratic Convention—we originally shot the whole speech at the Democratic, and that didn’t work, it was too much. So we went back with another—it’s the moment he comes out onto the stage, as opposed to delivers a speech. And marketing was an issue, because … Universal was balking—it was an 18, supposed to be a $17 million film, and it was a 19 or $20 million film, and they were very upset and didn’t want to spend that much money. And Cruise had to get involved, and you know what I’m saying, the way these things work, they put up enough money to open the film—thank God. Because frankly, the day that we opened the film, December of 1979, ’78—

RK: ’89.

OS: ’89. Oh, I’m sorry. December of ’89, we invaded Panama the same day to get rid of General Noriega. Which was pretty outrageous, a kind of military exploitation of a situation. That we were sending troops, basically, to invade Panama. We had no legal right to; it was complete intervention, and flouted international law, which was the beginning of a whole new period in American intervention abroad. So it was interesting. That killed our box office a bit the first day; everybody was on the flag—hello, Narda [Zacchino, journalist and wife of Robert Scheer]—waving the flag, everybody was saying America and Panama, we’ll get rid of this bum Noriega. And it didn’t do great business that first weekend, but enough to survive, and we got it to grow, and we grew through the Christmas season, thank God. And it never made as much money, half the money of Platoon; but it was a perennial, it was a winner; it was, you sensed that it would go on like a flower in winter, a lotus in the mud, and it would be a good one. And it came, it always plays, and it’s recycled and it plays throughout the world. And Cruise got nominated, we all did; unfortunately they rolled out a platform several times but they never let Ron up. But they gave me one, and I felt terrible because Cruise didn’t get one, and nobody else except me and the editors, I believe the editors maybe something. And so, ah, these things are painful. That was a tough film. I remember I was sick during the shooting, got sick. And you were so vivid, you were so vivid; you were always there, you were rooting for everybody, you wanted this, couldn’t believe this dream had come true. I remember one detail: the house in Long Island, when I went out with you to Massapequa, was very small. Like, I was used to slightly bigger houses, this was—

RK: The house I had grown up in.

OS: Yeah, this sort of suburban, Massapequa—small corridors, small everything. Because I guess in the 1950s, they built that way. And I remember when we came to the set, the natural tendency is they always want to make things wider, bigger because of course, it’s a Hollywood production; you have to have cameras, and access and all. So, but I insisted that we squeeze as much as possible. And you see it in the film, because we shot it in … Cinemascope, amazing effect. To be in a wheelchair, very narrow; at the same time, you’re going very wide. And you put that in these corridors, and you fly down these corridors—it looks, it does hit you, the perspective changes hit you. And I have to say, it was a painful shoot. We ended up in the Philippines, and did the last section there, with the sun going down the last day, and we ran out of time. And we were shooting [Willem] Dafoe and Cruise fighting in the sand, if I remember correctly.

RS: So I don’t know if you want to talk about Cruise, but I feel he kind of gets a bum rap. You know, it’s like, his religion is no more bizarre than all the others, I think. [Laughter] I mean, religions have extremes and so forth.

OS: You’re an atheist, Bob, right?

RS: Yeah.

OS: Yeah, you are. But you’re an announced atheist? You are or not? I’m curious.

RS: Yeah.

OS: Bronx. A Bronx atheist.

RS: Well actually, my father was a Lutheran, my mother was Jewish, I participated as far as I could go. But my point is, you can make any religion look weird, and they all have their extremes, and cults, and what have you. But what hit me about the telling of the story is that Tom Cruise turned out to be a very serious person. And I know the memory that you had that—because we forget, Hollywood does [get], and deserves very often, a bad rap. But I know you [gesturing to Ron Kovic] told a story once where you were in the hospital, and we thought—I thought you were dying; I mean, you sounded pretty awful. And, but Tom Cruise filled the room up with flowers, and—well, you had a very different impression of this guy.

RK: Oh, yeah. I mean, every Fourth of July since the movie has been made, I’ve sent Tom a birthday present, and he sends me, he usually sends me some roses. And that’s gone on since—how long has the film been out?

OS: That’s why you sent me roses the other day! I didn’t understand.

RK: It was your birthday.

OS: No, but the first time you sent me 12 roses that were so fresh, like Grade A roses, you know. [Laughter]

RK: I sent you 24, 24!

OS: Twenty-four, excuse me!

RK: Twenty-four roses. It was Oliver’s birthday on Friday.

OS: I counted them.

RK: Oliver’s birthday on Friday, and I sent him 24 roses. It’s about time I sent him roses, yeah.

OS: Thank you. I love roses. But that’s funny. I didn’t know the symbolism of you and Tom’s love affair. [Laughter]

RK: Well, hopefully ours has begun now. [Laughs]

RS: OK. My fear about the way we teach about media in our school here—this is all about careerism trumping everything, it’s all about success, how do you get to the top of the heap, and so forth. And you know, you’re a very—you’re one of the most successful directors in film history. And the range of your films. And you’ve [gesturing to Ron Kovic] been very successful as a book writer, and getting a movie made, and surviving, being a political example and so forth. So we’re not talking about two losers here. [Laughter] Yet we’re talking about two people who took risks, who have values, whether people agree with you or not. You know, no one could ever say that, either of you, that you don’t have values that you stand up for, that you’re willing to take risks for. And that’s true of a number of, quite a few people around in this Hollywood world, the media world; maybe not as much as one would like, you know. And so let me ask you why, how? What are the obstacles? Can you have a meaningful life as an artist without selling out? What are the pressures you faced?

OS: To a degree, Bob, I think everything is degree. You know, I can only go so far along my path, and there is resistance everywhere, all along the way. And it’s how you deal with it. Some people are very good with resistance, some people get rigid, some people are flexible. I’ve had various reactions to it. The resistance—I feel like consciousness, the older you get, the more you figure out or know; maybe I’m wrong, maybe it goes the other way. But in other words, the deeper into the shit you get, into the swamp, you don’t get out that quick. So in other words, the more conscious you become—like, Ron knows this—it’s hard, man. And every war becomes the war. And he goes out there and he appears, and he’s against war in general, a Eugene Debs, in that sense. But you know, I’ve been, coming from a different background, I’ve been fascinated—I came from the other end of the spectrum. He grew up Polish, you know, in Massapequa—

RK: Yugoslavian.

OS: Yugoslavian. [Laughs] So you know, he comes from another complete world. I had to travel a long fuckin’ way to understand the way the world works. And I say that kind of naive about it; Bronx, you [gesturing to Robert Scheer] was in the Bronx, you probably got things from your parents very quick. I think you did. I’ve heard your background, when you talk about the Cold War. You understood the Cold War back in the 1950s, it seems to me. I didn’t. Cold War is a whole other story, and Bob tells the best story about it. But that’s what we had. You see, Ron is there; we’re there because we’re products of that Cold War. And getting rid of that bug, that monkey off my back took a long time. In the ’70s, Born on the Fourth of July was part of that. Richard Boyle, this character he knows, part of that. Education, as you go, takes time; all the things you believe have to be stripped out. And all of a sudden, OK; we get through the Reagan period, but then we hit this 1989, this horrible year, Annus mirabilis, 1989, Ron—that was the year our film came out. The same day that our film comes out, we invade Panama. You understand the ambiguity of this thing. It gets worse. From ’89, when we should have had peace—peace dividend, there was no enemy, the Soviet Union was gone—things supposed to change. Beautiful springtime of our lives, could have been the best year of our lives. And it didn’t happen. And it’s a fascinating story, why it didn’t happen. And we tried to tell it in our [2012-13 documentary series] “Untold History of the United States,” because it’s a key moment for me. And you [gesturing to Scheer] probably, too. Because I think you got fired about this. [Laughs] No, no—you—no, you continued on. You fought against the Iraq War, and the L.A. Times turned on you, I believe, in 2004, correct? So you had about 14 years to go. I was still, ’89 was a shock. But I was fully engaged in making one movie after the other without stopping; it’s important not to stop and think. And I kept going and going, until one day, you know, I couldn’t go on like that. By that time, we had moved on to 2001 and a whole other era. So you’re, I don’t want to talk about everything up front, but just tell you that my education has been a difficult one, and I’ve had to give up so many of the things I thought. How do you feel about that?

RS: Well, you know, in Wall Street you mentioned your stockbroker father, who you dedicated the movie to.

OS: That’s correct.

RS: So he was a good stockbroker.

OS: He was the Hal Holbrook character, Martin Sheen character, in Wall Street, if you see it. My father, I respected him deeply and loved him. You met him, Ron.

RK: Yeah: Lou.

OS: Lou. And you know, so—but I had very ambiguous feelings for Dad. I gave him LSD when I came back from Vietnam; I wanted to wake him up. [Laughter] So you know, you understand, there’s a lot of ambivalence toward my father. But a lot of the things he taught me were wrong, and it took me a long time to learn that.

RS: Why did you leave Yale?

OS: Robert, that’s a much earlier story, that’s going back to ’65 and ’6-’7. There were issues that were—but they’re earlier issues. I wrote a book about it called A Child’s Night Dream, and I listed all those issues, ’cause I wrote it at the time, in ’66-’7. I wrote it then, but then I edited it; it came out in ’97 from St. Martin’s. I talked about a lot of stress of being young, privileged, and also at the same time—I wish I had some of the family that Ron had, the brothers and sisters—there was a bond there. And you probably had the same thing in the Bronx, you had brothers and sisters. So I didn’t have that, you know; I was in a boarding school at 14, shunted away; my parents divorced secretly; I mean, I didn’t even know this was going on. So there was a whole kind of sense of betrayal. Some people say … Stone never grew up, never recovered from the divorce, he blames the Vietnam War on his parents’ divorce, which is horseshit. [Laughter]

RS: But you did make a movie on George W. Bush—we might as well get through some of these—who was at Yale with you, but you didn’t know him, right?

OS: No, but I knew his type, certainly, and there was a lot of them in boarding school—third-, second-, third-generation. He was a third-generation Yale boy. I was a second generation. … His parents were—yeah, he was definitely entitled and privileged. And that’s exactly what I didn’t like about Yale; I didn’t like those kids. I thought that there was—you’d laugh with them, there was a lot of things to like about them, and I met many of them later in life. But there was something inherently wrong for a Yale boy who doesn’t go into the military to serve his country, becomes a National Guard, entitled in a special privileged position, and ends up not going to the war, and ends up like Clinton and like Obama and like the rest of them—and Trump—preaching war and going to war. So what Mr. Bush did in 2004 in Iraq is—2003—is unpardonable. Unpardonable. And we’ve suffered from, the country has been taken for a ride on this thing, a whirlwind; it’s historically shocking, and will be remembered, I think, by some people who care.

RS: So it’s an interesting connection, and we’ll take a break in a few minutes and then come back and see these clips. But one of the best books written about the Vietnam War had the title—David Halberstam’s book had the title The Best and the Brightest. And this war, just like the banking meltdown, came also from the best and the brightest. I happened to speak at the Kennedy School at the time of the banking meltdown, and I started with a question: How did Harvard get to be such a den of iniquity? [Laughter] Why does so much evil come out of what is the most prestigious university in the country? How come so many of its graduates went to Wall Street to steal people’s homes, to destroy their lives? Do they have courses in destroying family lives? [Laughter] You have to be very good at it, you have to be ingenious to develop the rules of the road that allow some to get rid at the expense of others. Well, the same thing is true of war and peace. How do you get a kid [gesturing to Kovic] from Long Island, living in one of those little homes, to get all excited about protecting this country, and volunteer, and go over there and get his body destroyed? How do you get him to do it? And the people justifying it were the best-educated, smartest people in the country. You know, you can make fun of Trump, but Trump also went to the Wharton School. He’s well educated, you know? But the fact is, the people who got us into these wars—which they can’t justify now, OK—they were the brightest people. Right? So, and yet this is the result. Anybody here got a thought about that, or want to say something about it?

OS: Well, I would differ just to say that Jack Kennedy may have gotten us into Vietnam, but he was going to get us out, and it’s very important to notice the difference. And he was a bright, bright kid, and he saw the disaster ahead.

RS: Yeah, but the big question–

OS: There are exceptions.

RS: OK, but I mean, the big—

OS: And [Franklin Delano] Roosevelt, too.

RS: OK, but hold the microphone, now—

OS: Roosevelt went to Harvard, and Kennedy went to Harvard, so Harvard’s not all bad. [Laughter]

RS: I know. But I want to—

OS: Kissinger went to Harvard, therefore that’s bad. [Laughter]

RS: Well, Daniel Ellsberg also did, and by the way, so did—

OS: And so did, so did the Bundys and the [inaudible] and those assholes.

RS: All right, but the question I’m putting to you is basically, your three movies, and all of your movies, really, are about mischief-making. It’s about the callousness with which we destroy people’s lives, the insensitivity, you know; the no regrets, OK. No accountability. And I could go through all of your movies; it seems to be a common theme, you know. That the people who are supposed to be sensible turn out to be a bit nuts, irresponsible, greedy and so forth. And so the question is—and this is all taking place, by the way, in a democracy. Right? This is not taking, this is taking place in a society that’s supposed to take the best of everyone’s traditions. So how do you explain that, Oliver?

OS: Well, ask Ron.

RS: I’ll ask Ron. Go ahead, Ron.

OS: It’s an interesting, it’s political theory, here, so I’m curious what your take is. But you only get two paragraphs.

RS: The question, Ron, is—

RK: I’ll keep it short.

RS: OK. Your father was working in a—

RK: A&P food store.

RS: A&P store. My father was a mechanic in, I went to, I was in New York yesterday, and I went the other day down Little West 12th Street, where my father had his stroke at the machine after 25 years or more. And my half-brother, his son, had flown and bombed his hometown in Germany, you know, the whole drill, you know. And I was thinking about it. And these are the people who did not have much education, you know; they were doing their job, they were paying their taxes. My father never missed a day of work for 25 years, every year they’d give him a certificate. The way your [gesturing to Kovic] father is described in the movie, one of those good folks. And they keep getting screwed. They keep getting messed over, they keep getting lied to. In a democracy, right? Supposed to be the, you know, the best political system.

OS: I would argue that Ron’s father would feel differently. He would say, I got the best out of America, they gave me my house in Massapequa, I owned it, I made it through, I got pension, security, hospitalization—

RK: I raised my kids, I raised my kids—

OS: —and I got my mobile home, and I traveled the last 10 years of my life.

RK: Yeah, and I raised my kids, they all—nobody ever went hungry, and you know, I did pretty well. You know, my father was proud of the fact that he had worked very hard at the A&P, and bought that motor home, moved to Florida, had a heart attack, overcame the heart attack, and they traveled all over the country in that motor home. And you know, camped out in front of a Wal-Mart or whatever it is.

OS: What would you answer, Bob—what’s your answer, your father’s answer to Bob? What’s wrong with America, right?

RS: Why did they [inaudible] …

OS: I’m asking Ron.

RK: My mother and father both served during World War II in the Navy; that’s where they met, they were working in the same office building in Washington, D.C. My mom was essentially, you know, pretty much a secretary, and she met my father and they were married. I can remember they received secret clearance for the work they were doing that had to do with the Japanese—there were just a lot of people, it was a huge bureaucracy, but it was breaking the Japanese code, and—

OS: I think Robert is asking you, what is their patriotism at the end of their life, after your accident.

RK: Oh, it changed. It changed. Even my father, who was last to change. You know, my father who was very conservative. And—I mean, the fact that I came home the way I came home, they came to the hospital, they saw—and they saw me suffer. They saw me come home drunk in a wheelchair numerous times, not just that one time in the movie that you showed, that you depicted with Tom. But just the times I cried in front of them, later, and you know, when I tried to share with them some of the terrible things that had happened in the war, some of the, you know, that fact that I had killed someone, that I’d pulled the trigger, that I’d had to live with that. The, just trying to connect to them, they—I mean, in the end, they were really the only ones who were listening to me. And my mother, my mother; I remember my mother writing an unpublished book. My mother wrote several, she published one book, and she—my father paid to have it published. But she wrote many; my mother was a wonderful writer, she wrote many unpublished books. And one of them was called, let me see; something about the war and what it had done to her son. And I remember that. No, she grew to hate the war, and what the war had done to me. And she was very bitter, and my mother was very bitter at the government for sending me to war. I remember that clearly. I remember my mother cursing not just the war, but cursing them out for what they had done to me; I remember that. I mean, my mother knew I was protesting the war, and she turned against the war also. And even after the war was over, it was all over, she hated what had happened, and she hated—she really was angry at the government for what had happened.

OS: Can we say there’s a difference between World War II and the wars that followed?

RK: Absolutely. Absolutely. Now, I mean, they—my parents, my parents had been a part of that, the baby-boom generation, been a part of that great victory of World War II, and they’d come home from that, the greatest, so-called Greatest Generation. But—I don’t know, having—I think the personal level, having it come home to your house, having it be your son, having it be the son that you raised, you know, the boy, the innocent boy, the Little Leaguer, the Cub Scout, the Boy Scout—having that kid come back with three-quarters of his body mangled or gone—I mean, that’s got to, that’s got to affect them. And it affected my father, too, deeply. My father was last to change. You know, my father was—my father was very, very—I remember asking my parents, this was years, years after the Second World War had ended. I was, I had to be in my ’40s, even my ’50s, when they were still alive. And I said, I said, What was your secret clearance? What was this? You can tell me now. They wouldn’t tell me. They would not tell me after all those years. They said, we swore an oath that we’d never tell. I said, Mom, the war is over with! This is, you know, 30, 40 years. But so they still—I found that very interesting; they held onto that commitment that they had made while in the service, that commitment to that top-secret clearance. That they would not talk about it, were not allowed to talk about it. I found that very unusual.

OS: So what Bob’s saying is, your parents got screwed. That’s what you’re saying, right, Bob?

RS: Yeah, I’m saying—you know, it’s interesting, our president’s speech today. Because he—there was like three speeches in it.

RK: No, but wait a second, Bob. Oliver’s making a point here, I mean, about my parents, and I’d like you to respond to it.

RS: I am going to respond to it by talking about my own father. And so, ah, it’s interesting. Because the president acknowledged that different people have different allegiances, and different ways of living. So there was a part of the speech that entertained the notion of complexity, and people have to make their own history, and you can’t tell them what to do, they have a right to do it. And then, another speech came and he said, but if they make decisions that I don’t like, I’m going to obliterate them. So we went from, boom, people have to make their own history, we shouldn’t tell them what to do; on the other hand, Iran, for example. Iran—that was the country that got—was more than Korea. Iran–oh! They’re going to go. Well, what’s their great crime, OK? He didn’t talk about Saudi Arabia, he didn’t talk about the Sunni religion, he didn’t talk about, you know, if you want to talk about terrorism and 9/11, Iran has nothing to do with 9/11. But in his speech, suddenly they were the bad people. And he’s going to tear up the peace agreement, whatever, the deal we have. And probably go to war. Ignoring the fact that the government, the society of Iran was totally changed by the fact that the United States intervened in 1953, ’54, to change the government, overthrow the government, etc. So there was no accountability and responsibility. Long-winded way of setting up our fathers. My father came from Germany, OK; immigrant, like Trump’s father. And it happened that my father’s family in Germany followed a guy who also talked that he was going to make Germany great again. Right? Wasn’t that the slogan? Germany had been great, then it had been humiliated after World War I; they were the best people in the world, right? They were the most scientific, best educated, right? The German people? Followed the Catholic religion, the Protestant religion, great art, best art in the world, best science in the world, best educated people in the world, cleaned their stoops. But somehow—and I’ve been back to Germany, I don’t know, 15 times or something; I had a best-seller in Germany, I’ve been on television and what have you. And I found my father’s family, and I found my uncle who had been in the German army and been at Stalingrad, and had been wounded. I spent a lot of time; my wife was with me on a couple of these trips and everything. And I said, what—why did you folks, who now seem so reasonable once again, right—how did you follow this madman, this guy with the funny little mustache—didn’t have orange hair, but he had a funny little mustache, and so forth—complex. How did that all happen? You know, what was this all about? And what got you to go along with ending up in Russia killing 50 million people? By the way, Trump today in that speech, he praised the English for their involvement in the war, yeah. They were never conquered. He praised the French, patriotism for taking on Germans. The French actually, the only ones in France who really did a lot of fighting were the socialists and communists; he condemned the socialists. And then he mentioned Poland, where again, there wasn’t that much of a resistance, though it certainly came more from people Trump might not like. He didn’t mention Russia. By way of introducing your documentary. He didn’t mention Russia. Oliver did a whole series on the Cold War where he points out the Russians took the brunt of the fighting in that World War II. They lost 50 million people; we were very late to end it—

OS: 25, 25.

RS: Huh?

OS: 25.

RS: 25. But all over, with the families, the result after—

OS: No, no, 25 million. Oh, with the families, yeah.

RS: OK, but 25 million. They took the brunt of it, and we were very late to end the war. But if you watch that speech today, they’re not even in the picture. Right? They weren’t there, OK. So my experience, if you ask about—yeah. I would say my father, whose own son—Japanese were not allowed, you know, Japanese were rounded up and put in internment camps. A very much smaller number of German-Americans—OK, why? They were white, OK; they were the largest immigrant group in the country and still are, German-Americans; and they, as opposed to the Japanese, who could only be in the Asian theater if they were used as translators, the Germans were allowed to be in, to fight in Germany. So my father’s son, my half-brother, he was in the Air Force; he bombed our hometown in Germany.

OS: So where does that all bring us?

RS: What I’m saying is, my father was a man who was perplexed by how could the society that he had respected most, right—valued the music, the language, everything about it—become the most barbaric society in the world? So then we get to our own society. And what’s left out of the discussion, but I think is discussed in your film, the fact is what we did in Vietnam was barbaric in the extreme. What we did in World War II, but you could say oh, there was a justification. And Korea, which is in the news now, North Korea; where did they come from? Rocket Man, he referred to. Who are these crazy people? How’d they get to be crazy? We know Koreans are not genetically crazy. There are a lot of Koreans here in this community. They do quite well, they run nice businesses, they design things and so forth. How did this, North Korea, how did they get to be so crazy? Well, one factor in there is this place North Korea was leveled by something called the Korean War. All right? There was very few buildings that were standing after. More bombs were dropped on North Korea during this Korean War, which you probably didn’t even study in high school, than were dropped on Japan during the war. Have you seen that referred to in a single media count? A single one? A single reference to their history? How did they get to be who they are, you know? So what we have is a demonization of everyone except ourselves, and anything we do—this was at its highest point of an American president—anything we do is, by definition, virtuous. The reason that you’re a controversial filmmaker is, you dare challenge that view. Right?

OS: Yeah. And Ron taught me how. But you know, you have to go against your government when it’s doing the wrong thing. And what Bob has just said to you with this story, I hope you’re paying attention, ’cause he has really given you his personal life, is that you guys, you young people, many of you Koreans in here, you’re living through this time when he is saying, your teacher who has seen—80 years old, right?—you’re [gesturing to Scheer] saying that this so-called civilized society we lived in, you grew up in, you worship, where all the materialism comes from, your hamburgers and your television—that society is in danger of becoming a barbaric one, already has been on numerous occasions. And this balance, where is the line? I mean, Bob feels that we’ve crossed the line, because no one in our country—including Obama, by the way, who’s just as bad on history as Trump is—they don’t remember. When Obama went to D-Day, the 70th anniversary, he didn’t even acknowledge Mr. Putin who was there at the anteceremony[?]. You know, the Russians actually killed five out of every six German soldiers, which was the best, the biggest military machine in the world—the Germans were invincible, practically. And the Russians took out five of every six soldiers from the German side. But you have to think about that, what does that do for American and British and Allied forces? It means my, your grandfathers’, my father’s generation would have been heavily, heavily wiped out. Because more Americans would have died, millions of us, millions of us. And that may have led—you may not even be here if the Russians had not taken the brunt of this thing. Just, everything is personal; everything Bob said is personal to you, whether you’re Korean or American; you have a responsibility, you’re in this government now. You’re maybe 19 years old, maybe you don’t have that much experience. What I’m saying is, you better get some.

Audience member #1: First of all, Bob, thanks for putting this together, and it’s an amazing experience for us as an audience to have Ron, Oliver interacting and telling this story, sharing these ideas. But I wanted to ask you, as three people with a perspective on history, where you feel things went wrong. Because you’ve looked back on the past and you’ve seen good things; you’ve had positive feelings about World War II, about the 1950s, about the, you were talking earlier on, Bob, about how President Eisenhower was able to warn against the military-industrial complex. At what point did things go wrong? If you had to, are there many points? Where is the—could each of you nominate the point where we go off the rails?

RS: I’ll do it first. [Laughter] Ah, it’s interesting. Donald Trump referenced the second president of the United States, John Adams. And John Adams said, the seeds of the revolution in this country, you know, came before. And what John Adams is referring to, actually, in part was embodied in something called the Fourth Amendment in our Bill of Rights to our Constitution, right? Which is the provision against unreasonable searches and seizures by the state. And what John Adams had written was really a critique of what was considered the most enlightened society of its time, which was England. England had a measure of limited government, right? It had the Magna Carta, it had English common law, and so forth. And yet, the government of England, by extending itself in an imperial mission of controlling the colonies and denying them, by breaking into people’s homes without warrants and so forth, had lost the trust of the people. And the Constitution of the United States, which is what Donald Trump seems to have missed here, but in Adams’ word, basically embodied the notion of limited government, the sovereignty of the individual, the rights of the individual, to hold and check power. Any power, OK? The power of the good guys, because after all, the king of England had at one point been thought to be the good. All right? And the argument was that uncontrolled power, absolute power corrupts absolutely. Right? It doesn’t matter what the society says, it doesn’t matter what its pretenses are, and it doesn’t matter even what its claim is on ideology, OK? Or religion. That if it’s unchecked power, and this power gets into wars and imperial conquests, you will lose the republic. That was the wisdom of it, that’s why Washington warned against the pretenses of, right, of patriotism. And so that would be my answer, is that when the United States decided that it had to reorder the world, for this country, and get into the very foreign entanglements that our founders won, they began to lose the idea of a republic governed by the free. Because you can lie about war, you can distort, you can frighten people, and so forth. So let me turn to you [gesturing to Kovic], because I think that’s the message that your father and mother resisted, and then finally your mother came to understand, right?

RK: What were you going to say?

OS: I’m not so sure, I don’t know. I didn’t see that part of her understanding it, but you did.

RK: What did you remember about my mom?

OS: Well, as in the movie, I do remember—as in the movie, I remember her strength and anger, and the fights that you had—those stood out to me.

RK: In the early years.

OS: Well, that’s what we covered at that point in the movie.

RK: Well, when I came home drunk that night in the movie, and I was, you know, railing against the government that had sent me to the war, and over the dinner table about we have to fight communism, we have to—yeah. My mother was a strong anti-communist, absolutely. So was the whole neighborhood during that period.

OS: Sure. And they still are.

RK: Yeah. And—but my mother—but I mean, that’s when, that was your memory of my mother, but years later—I mean, I saw her more than you did. She changed. She did change. And—

OS: My father did too.

RK: Yeah. Your dad did too, yeah, as well. My changes, the changes—the question again was—the question again was?

Audience member #1: Well, it’s, where did the country go wrong? Is there a point where everything goes wrong, or where the problem really begins? Different points get—

RK: Yeah, my answer, my response to you on that would be on a personal level, myself. Would be, the night I pulled the trigger and I killed somebody for the first time. Taking a human life out of this world, what that did to me. January 20th, when I was shot and I lost three-quarters of my body and I was nearly killed. And—

Audience member #1: But so extrapolating back from that, do you see the collective involvement in Vietnam as being the moment when the country lost something very important?

RK: Absolutely. What’s the word, a watershed moment?

Audience member #1: Yes, that’s what I’m looking for.

RK: Absolutely. Now, the Vietnam War, I think people will look back and see it as an extraordinary turning point in American history. No, that war and people like myself, and what that war did to me and did to the Vietnamese people—I mean, that war shattered something within this journey, this American journey. It stopped it in its tracks. Something happened, and it’s never been the same since. And yet the warmongering continues. You know, the—certain lessons have been learned; I disagree with people who say nothing’s ever been learned, we’re just repeating the same mistakes. Millions of people did learn, did understand, were deeply affected by that war. Some of them are in this room right now, who lived during that time. We will never be the same, we will understand the deep immorality, the wrongness of war as a way of solving problems, the use of violence as a way of solving problems. So America did change, and people were changed profoundly. A great deal of the establishment, or the machine that continues on, that was not challenged fully during that period, that was not altered during that period—that continues on, and that continues to be a great threat to all of us as a country and as a people.

Audience member #2: So we’re going to, we’ve collated a few of the questions that we—

Audience member #1: Sorry, could Oliver respond to that question first? Sorry—

OS: Yeah, quickly, I’ll do it quickly. I think Bob is saying that this thing precedes all this. He didn’t mean Eisenhower, that’s wrong; Eisenhower, on the contrary, gets away with a lot because of his farewell speech, where he questioned everything that he had built up. He is the one who took us to 27,000 nuclear weapons. He is the one who created the military-industrial complex. His was repeated warnings and threats, and use of nuclear weapons in Korea, in Vietnam, with [Secretary of State John Foster] Dulles. He was not ashamed to go to a first use of the bomb in his strategies, either. He also pushed atomic power for that same reason. He loved atomic power. So Eisenhower is not your solution; I hear that and I feel it’s a cliche. Eisenhower did more than anyone—no, next to [President] Truman—did more to start this thing. But the guy who starts it is Truman, and no matter if you’re a Democrat or a Republican, it doesn’t matter; he did drop the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and there’s not one more symbolic moment in the history of the world than those two bombs going off. For some reason, it has stuck in the craw of a lot of people, including of course our supposed uncivilized enemies, the terrorists who mentioned it quite frequently. That is an act of terror, and it created tremendous fear and terror in the world, it went into our guilt, into our consciousness; we deny it, Americans love to deny it. But I can tell you, it is in us. And it’s going to haunt us. Certainly it’s the dawn of a new beginning of consciousness. And the Vietnam War is part of that. But it all goes wrong; with the Cold War, as Bob has said—you should probably restate that at some point—the Cold War was a farce, it was put over on the American people, it was a support of militarism that was insane given the real threat of Russia at that point in time. And one thing leads to another, and it’s decoupled into this madness now, where we even ended the whole Cold War in ’89, and did we stop? Not for one second. Who can delude himself any longer? Who can delude himself about the desires of the United States to be the sovereign, single power in the world, the only sovereignty that exists? There is no sovereignty in what Trump said. None of these countries are allowed sovereignty. You do one thing only: what the U.S. tells you to do.

Audience member #1: Thank you. Thank you.

RS: Are there questions?

Audience member #2: So, yeah, we’ve been collating the questions on Top Hat. We’ve had lots of questions relating to our theme of the class today about patriotism. So I wanted to lead with a question that’s kind of an amalgamation of a few of your concerns and points. And I was wondering if our guests could speak a little bit about the tactics used by the media today, where they basically say that going to war is patriotic. And then are any of these, which of these tactics do you find particularly abhorrent?

OS: It’s your turn, Bob. I’ve just spoken.

RS: OK. I think that—look, first of all, I want to pick up on something Oliver said which everyone seems to ignore. Yes, it is terrible, it is terribly frightening in every respect that an unstable regime like North Korea could be developing a weapon that could destroy large numbers of people. And even if they don’t develop a missile-guided, you know, that could take a nuke over, they can actually destroy Seoul, Korea; they can kill right now with conventional weapons. And our response to this sort of thing is to threaten to level them. So we’re sending a message that these weapons are usable, that they can accomplish some sane purpose. And the significance of dropping the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, whatever else you think about them, it’s the first time that we said, it is legitimate—we reacted in World War II by bombing whole cities in Germany and Japan to demoralize the civilian population, no question. But with these bombs, we specifically said, we want to kill a large number of innocent civilians. That’s called terrorism. These were not, they cannot be used in a targeted way. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not militarily significant targets. So we said, we have the right to kill very large numbers of innocent people to make a political point. That’s what every terrorist says. They say their cause is right, it’s God or it’s this or that. And then toward that end, we and then the Russians followed, and other nations, unfortunately, to develop more of these weapons. And we’ve gotten ourselves to a position where someone—you know, Donald Trump is our president—can be awakened tonight, and given effectively 12 minutes, will be told there’s an attack of some kind, whatever it is, and you have 12 minutes to decide whether to use these weapons or lose them. Right? And that’s one human being, right? A controversial figure at this moment. So the real question is, why hasn’t this been examined up to now? Right? I mean, what is the answer? Does anybody in our questions ask that? [Looks at screen] You know, that’s a good one. “What is missing from war movies that Hollywood can’t possibly portray? Are there any aspects that are too tough to depict?” Well, we had a few movies, a couple of very good movies about the whole question of destroying life on this planet with the use of these weapons. Right? One or two, three? OK? But basically, that got dropped. That got dropped, OK? And we agree to go to sleep on this issue. We continue to build these weapons, other people, Pakistan has what, 150 of these things, fairly unstable regime. OK, we don’t want Iran to have them, but you know, how are you going to tell countries not to get them when we keep having more and more? And then the question to you, Oliver, is how does Hollywood work in relation to these big issues? And you could take any number of issues. Why was Hollywood for so long indifferent to race? Why was it so long, and to this day, indifferent to class? Hardly ever described the life of the really ordinary, a few exceptional movies; gender issues, all the whole range of issues. What–and the people making these movies know better, right?

OS: Bob, you know as well as I that money is the motivator. And if you don’t make money, they’re out. So everybody who runs the studio who has any kind of power has got to protect their ass first. I mean, what do you want to know about? If you can make money selling a race picture, you will. And certainly some of them have done much better. There are some very good films about nuclear war: Seven Days in May was excellent in 1962; On the Beach, 1960, On the Beach, excellent. And the first movie about the atomic bomb was The Beginning of the End, which was completely censored by—they jumped on MGM, Truman’s administration didn’t want a true examination of that story. So they propagandized the film. That’s the problem; you just cannot have an independent thought process; if you want to make money with a movie, you have to be so clever you should write it in some way as a disguise thriller or something that you have to figure out a way to give that message. And you can’t be too anti-American, because you’re going to lose your audience, and they’re not going to distribute it properly. So, it’s a tricky question. Many film people have wrestled with this.

Audience member #2: And we’ve actually got a question in relation to this as well. Oliver, in terms of the media, did you sense hesitation from the studios for the project? Did this hesitation come from the fact the Pentagon won’t give money to films that portray what they have done negatively?

OS: Yes. That’s the—yes. We know that. The Pentagon—there’s a book that just came out, I don’t know the title, I forgot—but Pentagon and Hollywood, you’ll see plenty of history; CIA and Hollywood; what do you think these TV shows were? Alias, Homeland? They were all in some way supported by the agencies. Zero Dark Thirty. The CIA—the Bourne films—the CIA is very, very aware of this and works very hard to keep the homefront fueled. But the Pentagon provides the big hardware, the aircraft carriers, the helicopters, the—what’s the famous new helicopter? Anyway, that’s the kind of stuff—in Terminator you see plenty of it. Sometimes it’s not overt, but they certainly provide help and guidance. It’s very hard to make a film that questions the Iraq War with anything serious, or Afghanistan, or—what? Pakistan.

RS: How have you survived?

OS: I don’t know, man. I’ve barely survived, I think—

RS: Oh, come on. You got to make—

OS: —I wish I were 80, like you; then I wouldn’t have to worry so much. [Laughter] Another decade.

RS: You keep rubbing this in, Oliver. [Laughter]

OS: No, I’m very honored, I look up to you. I said, how the hell did that guy do it? Narda, do you have an answer?

RS: Well, sirs, look. You are, both of you guys are role models, OK? And the fact of the matter is, people struggle—another role model, I went to see a Broadway play the other day, Michael Moore. And I was amazed. There I am on Broadway a couple of nights ago. And you know, I went there with [journalist and Truthdig contributor] Chris Hedges, ’cause he’s mentioned in the thing and the guy gave us two tickets; we went. And this guy, he’s got a Broadway stage, and he’s, you know, he’s breaking the rules. He really is. He took what was kind of a dull format, the documentary, which you’ve—we should talk about that a little bit. And he took the documentary into a place to discuss controversial issues, do great education on those issues. Yeah. Now, you have been able—you’ve been able, this is—OK, this is a school of communication, all right? Want to get to the bottom line here. This guy had a great story to tell. We would never know about it. Some people would read the books; if you hadn’t come along and found a way to make this movie, it wouldn’t have happened. It broke the mold. And to make your earlier movie, Platoon. I’m not saying you’re the only one that’s ever done it. But you figured out, how do you get the financing? How do you put it together? How do you get the studio behind it? How do you get the distribution? And it wasn’t that you just developed some little app that sees to be the main thing we teach, you know. The fact is, you took this industry, and there have been others that have done it, but you turned it upside down. And we can go through the list of movies, and what is the skill set?

OS: I don’t know, Bob. I mean, it beats me. It’s like, film by film, and subject by subject, it’s a minefield. I’ve run into issues, and [my] movie was canceled with three weeks to go, like the [movie] in 2007, that was a beautiful movie, I thought, but… And I’ve had many setbacks you don’t know about. And you know, each thing—right now is not a time for me, I couldn’t probably get anything done in terms—Snowden was the last film. No support, by the way. That was, no U.S. studio was involved in the beginning. We got our financing from France and from Germany, which is quite a feat. Because in Europe, there was more appreciation of what Snowden did; the polling was much better. And we ended up making a small distribution deal here in the United States with a small company. And we were hurt by that; they hurt our release. But there’s an example. Snowden is a, should be a popular—put it this way, at least a considered hero in America. But no. Because the government has come down hard on him as a whistleblower and as a traitor. It’s very difficult to overcome this prejudice of this uneducated public that feels that he in some way, [that] he gave away secrets. No matter what he gave away, he gave away secrets, you see. This is a mindset. We can’t overcome it. Am I being too pessimistic?

RS: Well, yeah, because you did overcome it. The fact of the matter is, you—I mean, how many movies have you made?

OS: Well, that was the 20th, it was a feature film, yeah.

RS: Twenty. And then you’ve made these documentaries. And you know, they do have—

OS: It’s good, I’ve had a good run. Now, maybe it’s time to get off the stage, you know? What I’m saying, it’s very hard if I can’t make a movie about Snowden and it doesn’t do well in the United States; it is an issue. I’m working on a TV series, by the way, but that’s different, about Guantanamo; we’ll see how far we can do with that. It has to be entertaining.

RS: We have the Norman Lear Center connected with USC. And Norman was a guy who took television into a whole new direction, dealt with a lot of controversial subjects. So you can go look at the history of mass media in the world, but certainly in this country. And you find people who managed to turn the system against itself to exploit the contradictions or what- have-you. Right? And you know, you’re maybe bummed out at the moment—

OS: Bummed out at the moment, yeah. [Laughs]

RS: But the fact of the matter is, no one has had—I can’t think of anyone that’s had a bigger impact on our public’s thinking, on a whole range of issues, that you have had.

OS: Well, thank you, Bob. I really appreciate it, but I don’t believe you, and I think the class is into—they liked “Star Wars,” and they want to see the next one—

RS: But that didn’t change their consciousness.

OS: —and “Hunger Games” and stuff like that. I just don’t know where that’s going.

RS: It’s going—well, we’re going to get late, we’re not going to be able to answer this question. But I’m holding you up, both of you up as an example that you don’t have to go along—

OS: Yeah.

RS: You don’t have to go along, and you can actually have a—you asked me why, how I can do this and I’m 80? Well, first of all, I work out almost every day and I eat right. So if you want—maybe that’s the book I should write, rather than all this political stuff. [Laughter] But the fact of the matter is, there’s joy and struggle. There’s joy and not accepting it. Right? There’s joy and—I remember one guy, a psychiatrist, Roger Gould, great guy. And I asked him, I said why the hell am I doing this? I teach this class, then I got to write my columns, then I got to go work on—oh, oh! Am I suicidal? He said, ask yourself one question. Are you hitting the brake and the accelerator at the same time? Think about that question.

OS: Well, do you read the paper in the morning?

RS: Listen to me for a second. [Laughter] So I thought about that question, and I thought, in terms of what I do, what I do—no. I’m getting forward progress. Yeah, you get jammed, but you get forward progress. And I think what’s kept you guys going, and we only got another 20 minutes, so—but what’s kept you going was that you did not surrender to the odds. Right? And the fact is—right? So say something about it [handing microphone to Kovic]. Give us a positive message.

RK: Well, you’re our—you are our greatest director. [Applause] You’re one of the most, you are one of the greatest directors in our country’s history, and you will be remembered as a great American director. But you’re alive now, and you will make many more films. You will break through this. And you’re just beginning, you’re not ending; and I don’t want you to stop, I want you to continue. Because your best work may be ahead, it very well may be ahead. Because you have an extraordinary gift, and it has been a joy and an honor and a pleasure just simply working with you and watching you work. You’re an inspiration to everybody who works with you.

OS: Thank you, Ron.

RK: I had to say that, I’m glad I said that.

OS: Thank you.

Audience member #2: And we’ve actually got a question that kind of follows on nicely in relation to the odds. And do you think the odds have changed in today’s society, maybe compared to say 20 years ago? And with regard to that, do you think that Hollywood will portray the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan quite differently to maybe how you have been able to?

OS: I think everything changed to another level in 2001 when [George W.] Bush became president, with that fraudulent election. But everything changed in his dialogue after that attack. So Hollywood would never go back. It became more, even more ultra-martial and conservative. No question, no question. If there is an, if they overdo it, in a strange way, all this talk of wiping out North Korea, nuclear, easy talk about nuclear, is very sad and tragic. But if there is another war and we use a nuclear weapon, there might be a way that people would wake up in this country. There might be a way. It’s a sad thing to say.

RS: We can pass around the mic, get some energy here. Has anybody got a question? Want to ask in person?

OS: How about some of you people who live in Seoul, parents in Seoul?

RS: Come on, let’s get the energy up for 10 minutes.

Audience member #3: Hello. I’m Noah, nice to—thank you all for coming in today. I had written a question earlier on the feed, and it got a couple of likes, so I wanted to voice it. It’s for Mr. Kovic. Being a veteran and someone who’s experienced war, and not taking a side or stance on it, I was wondering what your opinion on Trump’s transgender ban on the military has been. Or what, how you personally perceive the ban itself.

RK: I oppose it. I oppose it, and I feel there are many gifted people who have committed many years of service, they’ve served in combat, they’ve been in Afghanistan, they’ve been in Iraq, and they—I mean, talk about patriots. They are supremely patriotic. They’re committed to this country. They’ve risked their life on behalf of this country, whether the policy was right or wrong. And in almost every case, it was wrong. No, I do strongly oppose it and I hope it’s not enacted. And I hope we learn to respect those people for who they are, not for their sexual preferences, but for the fact that they can do their job just as good as anybody else, and they’ve been committed to this country for a long time. They’re very important to the infrastructure of that military, and to ban them or to force them to leave is to harm, you know, harm our country and our people. No, it’s—let me just say I oppose it very strongly, yeah. [Applause]

Audience member #3: Thank you. [Applause]

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.