The magnificent career of Hungarian-born cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond received a small and delightful capstone in 2015 when movie-crazy TV chef and longtime Zsigmond-idolator Anthony Bourdain chose him as his guide to the mysteries and splendours of Budapest, where Zsigmond had studied cinematography at the State Academy of Drama and Film in the early 1950s.

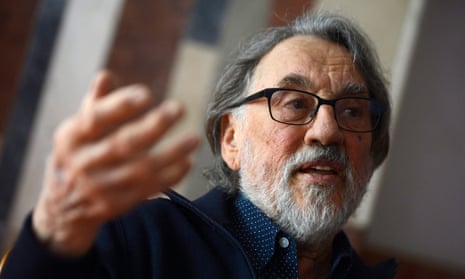

The 6ft 4in Bourdain was led around the city by this tiny and birdlike 84-year-old – armed as ever with his camera – who led him to the abandoned headquarters of the Soviet-era security services, to favourite old restaurants, and laid out his early life while sitting neck-deep and naked in one of the city’s legendary bathhouse pools. Exiled from Hungary almost 60 years earlier and domiciled thereafter in the United States, his accent was still thick enough to necessitate subtitles.

We think of Zsigmond, who died on New Year’s Day aged 85, as one of the leading photographic lights of the Hollywood New Wave, as the man who pre-fogged his stock for McCabe and Mrs Miller and rehabilitated the oft-despised zoom-lens in The Long Goodbye (both for Robert Altman), as the pictorial author of Deliverance, and for his Oscar-winning work on Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

And he was certainly all that. But one wonders what might have been, if the Russians had never crushed the Hungarian uprising of 1956 (while the world was busy deploring the Suez invasion), and if Vilmos and his lifelong best friend and fellow cinematographer Lázsló Kovács hadn’t filmed the invasion and fled the country with 30 cans of raw footage three weeks after the clampdown.

Ironically, in the aftermath of this inhuman squashing of Hungary’s urge toward freedom, the state authorities liberalised the country’s film-making infrastructure, adopting a hands-off attitude towards all but the most popular kinds of domestic cinema. As happened in Lodz, Poland, in Prague during the mid-60s and to some extent, at Mosfilm in Moscow, filmmakers were relatively free to make what they liked – the problem lay more with getting their work seen.

In Hungary, this resulted in some of the most extraordinary film-making of the Soviet era, including the technically astonishing work of director Miklós Jancsó, and his cameramen Tamas Solmo and Janos Kende. What might Zsigmond and Kovács have contributed to that New Wave, had they remained?

Zsigmond and the younger Kovács missed all that, however, having been deemed persona non grata at home after giving their raw footage to CBS News on arrival in New York. As Vilmos told Bourdain, “the Russian soldiers were under orders to shoot dead anyone with a camera”, so they were lucky to be alive at all. At 26 and 23 at the time, they understood effective and dramatic composition and the art of storytelling in images, and how to do both on the fly, and as the bullets were flying.

The power and immediacy of their footage still compels outrage and horror today. The story of their flight combines – in characteristically Hungarian ways – wide-eyed terror, near-lunacy and antic humour. As they told the makers of No Subtitles Necessary: Lazslo and Vilmos, a riveting dual-biography documentary, they dodged soldiers and snipers at the Austro-Hungarian border, made it across, and secured the footage in safety once in Vienna. Then Lazlo decided to go back across the border and bring his girlfriend over as well. He returned, but his girlfriend had already left, so instead he persuaded Vilmos’s girlfriend to come along as well. And then they crossed the border again. The folly and grandeur of youth – in spades.

In the US, they initially dwelt in a subterranean B-movie world of biker movies and exploitation flicks, industrial documentaries and TV spots. Zsigmond’s first notable effort – under the half-Anglicised name William Zsigmond – was The Sadist (1963), a five-handed, zero-budget hostage drama shot in a gas station and partly inspired by the Charlie Starkweather case that also gave us Terrence Malick’s Badlands. Its black-and-white cinematography still pops half a century later.

He also shot his most pricelessly Z-grade confection, Ray Dennis Steckler’s The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies (1964). Lázsló, meanwhile, made enough schlocky biker pics (Psych-Out, Hell’s Angels on Wheels) to earn himself the director of photography slot on Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider, which contains some of the finest landscape photography of the 1960s.

Zsigmond was also DP on Peter Bogdanovich’s debut, Targets, securing him work on subsequent Bogdanovich productions What’s Up, Doc? and producing the shimmeringly silver black-and-white of Paper Moon. He also shot two movies for Bob Rafelson, Five Easy Pieces and The King of Marvin Gardens. Together, Lázsló and Vilmos’s combined effect on the Hollywood Renaissance of the late 60s and 70s is almost impossible to overstate. The friendship was profound and lasted until Lázslo’s death in 2007. Kovács’s widow Audrey told the makers of No Subtitles Necessary: “Lázsló had one widow and it’s Vilmos. I think they were as close as two men could ever be.”

Vilmos took a little longer getting to the top, but when he got there, the results were stunning. For Altman’s McCabe and Mrs Miller, he took a technique (pioneered in black and white by Freddie Young on the Sydney Lumet/John Le Carre movie The Deadly Affair) of pre-fogging, or pre-flashing the raw stock with a little light before exposing it fully on set, while using Vilmos’s preferred Tiffen filters.

The warmth of his interior lighting and the richness of the whites in his snowbound exteriors was a giant step forward in the history of cinematography and the poetry it can produce. Witnesses on the shoot have said they could scarcely credit the difference between what they could see with their own eyes on the set, and what Zsigmond made of it with his lenses and lights.

He was never again short of work, joining Boorman for Deliverance and Spielberg for his early comedy-thriller The Sugarland Express. He also shot The Hired Hand, the directorial debut of Hopper’s Easy Rider co-star Peter Fonda, a film that uses formidably tricky and groundbreaking triple and quadruple dissolves of Vilmos’s footage in its editing.

If Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate was a disaster in terms of storytelling and logistics-mangement, one person on that troubled set did his job absolutely right, and it was Zsigmond; the colours he ecstatically evoked have rarely been seen since on film. In all his work he amounted to the co-author of the film, forsaking technical perfection for visual truth, beauty and conviction.

Above all, he loved the work, and kept at it right until the end. His last major credit was in TV, shooting 24 episodes of The Mindy Project (that Mindy Kaling, she’s always had excellent taste), a career arc reflecting that of one of his idols, Karl Freund, who shot Metropolis for Fritz Lang and The Last Man for FW Murnau, and ended up as the DP on I Love Lucy. Work is work, it depends on what you bring to it, and Vilmos Zsigmond brought everything, every time.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion