Ty Law was driven to prove people wrong, and that made him a no-doubt Hall of Famer

Law will be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame this Sunday in Canton, Ohio.

For NFL cornerbacks, the ability to forget is a survival skill. More than any position, cornerbacks require selective amnesia to shrug off unsuccessful plays and confidently own the next one. Ty Law displayed a short memory on the field, but it’s the long memory he possessed off it that paved his path to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The cocksure Patriots corner who excelled at draping himself over opposing receivers will be draped in a gold jacket in Canton, Ohio, Saturday, when he’s knighted with football immortality along with seven others. He arrives there thanks to total confidence and total recall. Law never forgot a doubter, a diss, or a slight, dating back to his days growing up on Wykes Street in Aliquippa, Pa. He was motivated and molded by them all.

Law remembers people saying he was good after leading Aliquippa High to a state title in 1991, but not good enough to play at the University of Michigan. (He started as a true freshman.)

He remembers writing to the NFL Draft advisory board before he left Michigan in 1995 and getting a letter back that said he would be picked between the fourth and seventh rounds. (The Patriots selected him with the 23rd pick of the first round.)

He remembers the disappointment of New England fans when his selection was announced, some booing. (He finished his career tied with Raymond Clayborn for the franchise record for interceptions with 36 and nabbed arguably the biggest one in franchise history in Super Bowl XXXVI.)

He remembers having to convince his first pro coach, Bill Parcells, to trust him to shut down the opposing team’s top receiver. (This became a specialty of Law’s during his 15-year career, 10 of those seasons in New England.)

He remembers people saying he wouldn’t be the same when he returned from the broken foot in October 2004 that ended his Patriots career. (He led the league in interceptions for the New York Jets in 2005 with a career-high 10.)

He remembers people saying he was a talented corner, but not Hall of Fame material. (He’s the fifth longtime Patriots player and the second corner to be elected to Hall of Fame, joining Mike Haynes.)

“There was really no weakness in Ty’s game,’’ said Bill Belichick (right).

Beat him for a big play, and it hardly made a dent in Law’s temporal lobe. Doubt him, and it was seared in his mind forever.

“That stuck with me more than somebody actually beating me on the field because that’s more of a long-term effect when they doubt your abilities,’’ said Law. “But I live to prove somebody wrong. I trust myself. I believe in myself, but if I have to make you believe in me by my performance, you’re going to understand what I’m about.’’’’

The amalgam of Law never forgetting doubts, never doubting himself, and playing with the rude physicality of a bouncer and the lithe footwork of a ballerina forged a Hall of Fame cornerback whose penchant for game-changing plays made him one of the best of his era.

“There was really no weakness in Ty’s game,’’ remarked Patriots coach Bill Belichick. “He was good in coverage, good on the jam, good against the run, and he could change the game with his ball skills.’’

A five-time Pro Bowler and two-time first-team All-Pro selection, Law is the first core player from the Patriots dynasty to be enshrined in Canton. He was a member of their first three Super Bowl title teams (2001, 2003, and 2004). Law is the ideal representative for a football dynasty birthed and fueled by an us-against-the-world mentality.

A good bet

Ask any of his former coaches and teammates about Law, and what instantly comes up is his uncommon and unshakable confidence. Law has lived by a mantra he has repeated since he was running around for the Aliquippa Little Quips in Pop Warner, reversing field as a running back to score on the 48 Pitch play: Bet on yourself.

In a Sports Illustrated story in 1999, he boasted that one day he would be in the Hall of Fame.

Former Patriots linebacker Ted Johnson was part of the same 1995 Patriots draft class as Law. Johnson was taken in the second round, sandwiched between Law and another Hall of Famer, running back Curtis Martin. Johnson said his first impression of Law was that he exuded supreme confidence, even as a rookie.

“Whenever you see a guy stand out amongst other guys as far as his confidence and self-assuredness, you just always made note of that,’’ said Johnson. “That was always Ty.

“I would never see the guy down. I would never see the guy discouraged. I would never see him beat himself up.’’

Law’s confidence was contagious among his defensive teammates.

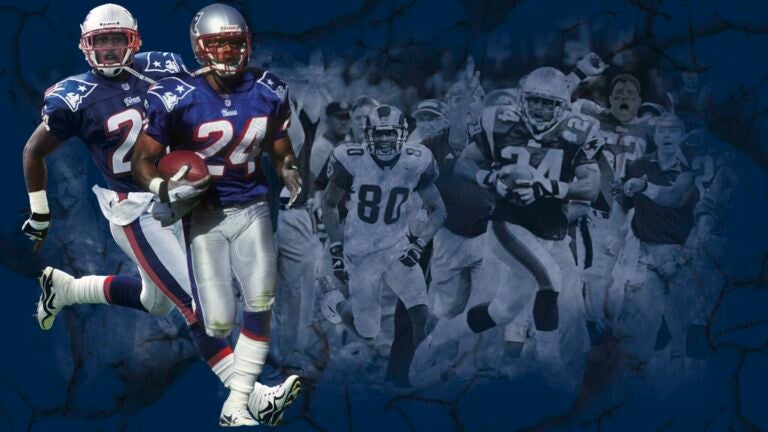

Law could instill that confidence in his teammates. His 47-yard interception return for a touchdown off Rams quarterback Kurt Warner in Super Bowl XXXVI, putting the Patriots up, 7-3, in the second quarter, was a signature play in one of the biggest upsets in NFL history.

“I just remember that being like, ‘Oh, man, we’re winning this game,’ ’’ said Johnson. “That was a play where I literally for the first time thought, ‘We’re going to win the Super Bowl.’ So that was a huge, huge, huge play in that game as far as our collective confidence, feeling like, ‘We got this.’ ’’

Law loved to torture quarterback Tom Brady in practice and talk trash. He publicly called Belichick a liar while trying to shoot (from the lip) his way out of town during an acrimonious and ugly contract dispute before the 2004 season that paved the way for his release the following offseason. He was known as a gambler who went for the big play, the big hit, and the big payday.

Law’s confidence “is and was off the charts,’’ said former Patriots defensive coordinator and current Houston Texans defensive coordinator Romeo Crennel. “He felt like he could cover anybody. He didn’t care about who it was. He accepted the challenge and looked forward to the challenge.

“Sometimes because of that confident personality some people think that he didn’t have to work at his job. He worked at his job. He would run a couple of miles a day in the morning before practice because he knew that his job required some stamina.

“He would put that time in getting extra running and conditioning in before we went to practice. I think that was one of the things that made him so successful.’’

Hills to climb

Law was blessed with great ability, but his greatest talents were his propensity for hard work and his willpower. Both were instilled in him growing up in the hardscrabble environs of Aliquippa, a steel mill town where football is both religion and diversion. He grew up in a place where people didn’t give up or back down.

His climb to pro football’s apex started with him running up and down Griffith Heights hill in Aliquippa. On hot summer days, Law’s lifelong best friend and Hall of Fame presenter, Byron “Book’’ Washington, would implore Law to abandon his grueling workouts to cool down by the pool.

He might as well have been asking Law to stop breathing.

“Since he was little, he always had a work ethic out of this world,’’ said Washington. “We’re about 15 or 16 years old. It’s hot days in the summertime. He wants to go and train. I’m like, ‘Cuz, it’s too hot. I’m going swimming.’

“He was a talented guy anyway. But he always did extra to just make him better. He always went the extra mile. This hill is a monster. He used to run up and down it about 10 times, whatever it was, hot, cold, raining, it didn’t matter. He had a goal. He knew what he wanted to do.’’

He wanted to play in the NFL like his uncle and idol, Hall of Fame running back Tony Dorsett. Law would spend summers tailing Dorsett. Now, he’ll follow Dorsett, Mike Ditka, and Joe Namath as Hall of Famers from Beaver County in Pennsylvania.

Law also knew what he didn’t want to be. As he revealed in The Players’ Tribune, Law briefly dabbled as a drug dealer as a teen. He knew that life wasn’t for him. That it was a dead end, literally and figuratively. Law said football and the guidance and discipline of his late grandfather, Ray Law, “saved my damn life.’’

Law’s grandfather, who was a supervisor at the Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation mill in Aliquippa until it shut down, provided the strong male role model he needed. (Law’s mother, Diane, had him at age 16 and dealt with personal struggles; his late grandparents, Ray and Ida, helped raise him.) His football dreams provided the structure and focus he needed.

The time is right

It’s fitting that Law is going into the Hall of Fame in the Year of the Defensive Back, joined by Champ Bailey, Ed Reed, and senior committee selection Johnny Robinson, the first time that four defensive backs have been inducted in the same year.

Law’s résumé speaks for itself. He was a member of the All-Decade team for the 2000s. He twice led the NFL in interceptions, becoming the first New England player to do so in 1998 with nine. He finished his career with 53 interceptions and seven touchdowns in 203 games. Law had an additional six interceptions in 13 postseason games, four of those coming with the Patriots.

Law’s career is littered with great memories and great games, like the three-interception effort he had in the 2003 AFC Championship against Peyton Manning and the Indianapolis Colts. If there’s a hallmark of those first three Patriots Super Bowl title teams, it was the ability to suppress some of the high-octane, high-flying offenses of the era, the “Greatest Show on Turf’’ Rams and Manning’s Colts.

The Patriots did it so well that Colts president Bill Polian persuaded the NFL’s Competition Committee, of which he was a member, to make illegal contact on receivers a renewed point of emphasis following back-to-back playoff losses to the Patriots during the 2003 and 2004 seasons. Law was at least partially responsible.

“We neutralized their speed and their quickness with physical play,’’ said Johnson. “Ty was kind of the tip of the spear when it came to that. The best cornerback I’ve ever played with, obviously, hands downs.’’

Law finished with 53 career interceptions.

Before Law could master the moments in big games, he had to make a name for himself. One game in particular helped him do that. It came in his second season in the league, 1996, against the defending Super Bowl champion Dallas Cowboys. These were the three-time Super Champion Cowboys of Troy Aikman, Emmitt Smith, and Michael Irvin. It was a measuring stick for a Patriots team that would go on to play in the Super Bowl — and for Law.

Always the master motivator and manipulator, Parcells gave Law what he asked for every week, a shot to shadow the other team’s best receiver, Irvin. Law responded with two interceptions in a 12-6 loss.

“I said, ‘Put me on the top guy.’ I said it all the time,’’ said Law. “They were reluctant. I was a young guy. So he said, ‘You know what 2-4 [Law’s number], I got somebody that ain’t scared of you this week. He’s going to kick your ass! You intimidate everyone else. This one ain’t scared of you.’

“So he rode me all week. I swear he didn’t coach nobody else during that whole week of practice.

“That was the breakout game for me, and the rest is history. I got so much confidence from that. It was amazing.’’

Physicality was Law’s calling card. It’s what led Parcells to draft him.

“We had a tremendous need at cornerback,’’ said Parcells. “I wanted big, physical corners, and that’s what Ty was.’’

What separated the 5-foot, 11-inch, 200-pound Law from a Deion Sanders or a Bailey was that he was as adept at making tackles in the run game as he was at shadowing receivers anywhere on the spectrum from physical to fast.

“It used to be you wanted corners where you tell them early on that they have to tackle,’’ said Crennel. “Today, it’s more pass-oriented. You have ‘cover corners,’ and a lot of them think their job is just to cover. They don’t have to tackle. It’s not part of their job description.

“He could cover and was more than willing to tackle.’’

Willie McGinest remembered that Law would be apoplectic when the team substituted him for a safety or a linebacker in short-yardage situations

“Sometimes in short-yardage when the corners had to come out, we would tease him,’’ said McGinest, “and we would be like, ‘Strong, physical, tough guys in. Little guys, out!’ He would get upset.’’

Last stop, Canton

Law went hard on the field and off it. That’s the Legend of Law.

Johnson recalled showing up one day at 6:30 a.m. after the players had their customary day off on Tuesday. He was pulling into his spot at Gillette Stadium when a limousine pulled up.

Law stepped out with blankets and a sleeping bag and greeted Johnson, telling him he just got in from New York City. Law paid the limo driver, turned to Johnson, and said, “All right, man, let’s go to work.’’

Law got in his usual pre-practice conditioning, running the stadium stairs, and then dominated in practice.

Law (front row center) appeared at the recent Patriots Hall of Fame induction ceremony for Rodney Harrison and the late Leon Gray.

Things didn’t end that well here for Law in 2000. After the Patriots defeated the Buffalo Bills in a driving snowstorm, Law, Troy Brown, and Terry Glenn stayed behind because they were afraid of flying. Law ended up partying at a nightclub across the Canadian border. When he tried to return to Buffalo, he was stopped by US Customs and the drug Ecstasy was found in his bag.

Law apologized and said the bag belonged to a relative who was staying with him. But he was suspended by Belichick for the season finale against Miami, one of a few run-ins between Law and Belichick.

But Law and Belichick buried the hatchet long ago. On Monday, following the Patriots’ in-stadium practice, Law snapped a photo of his daughter and her friend with a beaming and avuncular Belichick, who praised Law on making the Hall of Fame.

In Law’s mind, Canton was always his final football destination. He never doubted it for a minute. The doubts always belonged to everyone else.