“It’s going to sound bad, as if I am glamorising it, but it was normal,” Troy Deeney says when he remembers being driven around by his father in a stolen Mercedes-Benz with a drug dealer locked up in the boot. Deeney was just 19 years old and he had played one of his earliest games of professional football for Walsall against Northampton Town. He was a dozen years away from becoming the Premier League football captain who would do so much to force debate around how leading clubs in England could confront enduring racism.

Early in 2009, however, Deeney was simply puzzled by another outbreak of chaos in his life. Hearing the hammering and screaming in the boot of the car he turned to his father when they stopped for petrol. “Can you hear that noise, Dad?” he asked.

His father, whom Deeney revered even though he was such a violent man who was in and out of prison, shrugged. “Don’t worry. I’ll drop him off in a bit.”

The kidnapped man was a drug dealer who owed money to a friend of Deeney’s dad. Having filled the stolen car with petrol, and cranked up the music to drown out the commotion, Deeney’s father smiled. “I’ve fed him and he’s fine. We’ll drop him off later and I bet he pays.”

On a quiet October morning, deep in the midst of a long and involving interview about his life and powerful new book, Deeney is still trying to make sense of his traumatised past. “Of course it’s not normal to have someone in the boot but it was normal for us with our mad destiny. My dad never had a driving licence so for him to turn up in a blue Mercedes …?”

Deeney puffs out his cheeks and laughs softly. “It had reached that point when you just went: ‘Dad, I don’t even want to know.’ The only thing I wanted to know is: ‘Am I going to get in trouble?’ My dad said: ‘No, no, it’s my mate’s car, it’s fine.’ I now think: ‘Fucking hell, how mad was that life I used to live?’ I’m so boring now. I go to work and play with the kids. I walk the dogs. That’s as fascinating as my life gets now. It’s just a normal, generic, day-to-day life. But, yeah, the time before this was a bit strange.”

After 11 years and 419 games at Watford, where he became their captain and one of the most outspoken and honest voices in English football, Deeney was transferred to Birmingham City, his hometown club, this summer. It was in Birmingham, during the darkest period of his life in the summer of 2012, that Deeney knew he had to change. His dad, Paul Burke, who was his adoptive father and an infamous gangster in Birmingham, was buried on a Friday that June. On the following Monday, Deeney began a 10-month prison sentence for kicking a student in the head after a late-night altercation in Birmingham.

He and his mother, Emma Deeney, had often been terrified of Burke and the turmoil of their lives sparked the subsequent drinking and violence that led to Deeney ending up in jail. It is a subject he addresses in his book and, as he says now: “How many interviews have I done over the years? It always comes up. I could be talking about Asda and somebody will say: ‘You went to jail so let’s talk about that.’ But there’s another person on the other end of that [street fight] who is living their trauma through something I did. Every time he reads about me there is another reminder. What I did was wrong, which is why I wrote about it, so please can we close that book now?”

Deeney is more interested in examining the reasons which led to his imprisonment and discussing how he has used therapy to transform his life. His biological father had abandoned Deeney and his mother soon after his birth and that rejection eroded his self-esteem. In contrast, he says, Burke’s willingness to become his adoptive father was rooted in love despite the brutal mayhem of his criminal life. It is a typically surreal footnote in Deeney’s past that, on the day of the funeral, his biological father suddenly turned up to be the DJ at Burke’s wake.

“I call that the Deeney effect,” he says wryly. “My biological dad [whom Deeney loathes] is friends with my dad’s youngest brother. It’s all fucked up. I was one of the last people to arrive [at the wake] because I was at the grave. I walk in and he’s there. My biological dad, who I haven’t seen in years, is also the DJ. He’s the last fucking person I wanted to see but, because my mum was cool and didn’t make a fuss, I stayed quiet.

“As a family we don’t talk to each other. We’re from a Jamaican and Irish background where no one speaks. So one reason to write the book was to hopefully spark a conversation within the family. I’ve done a lot of therapy, 12 years of it, and I know we need to talk. My [younger] brother came over on Sunday and this sums it up. When my dad died he suppressed it totally. But I gave him the book and after the first two chapters he said: ‘I never knew so much of this.’ But he could remember the CS gas the police used when they arrested our dad in the house. So that sparked a conversation between us that we never would have had – and that has to be good.”

Deeney is admirably open about how his life has been gradually transformed by therapy. “I still see two therapists because I’m getting into the nitty-gritty now. There are layers in that blackened onion that you keep peeling back until you find the root cause – and for me a lot of my trauma is to do with rejection. My missus said: ‘I’m starting to understand why you can’t cry.’ It’s because I never saw my mum cry from all the things she went through. So why should I cry? I’m also from a generation where they’d say: ‘I’ll give you something to cry about.’ You cut yourself off emotionally. But I don’t want my kids to see that as normal. I want my kids to be in touch with their emotions. I’m 33 and it’s emotionally draining carrying that baggage.”

Beyond counselling, and his long and successful career as a reformed footballer, Deeney has also been calmed by having a purpose in speaking out against racism. At last year’s meeting between Premier League club captains, as they discussed how to resume football after the first lockdown, racial discrimination was the fifth and last item on the agenda. As the meeting on Zoom approached the end it looked as if racism, which had become global news after the murder of George Floyd, would not be discussed in any detail. It was Deeney, as Watford’s captain, who spoke up. He took over the Zoom call with, as he says now, “a big rant”. It had a galvanising impact and led to players taking the knee and wearing the Black Lives Matter slogan on their shirts.

“It was not through a lack of them wanting to do something but more a case of how do we spark that conversation,” Deeney explains. “Apart from the footballers on that call we had Premier League officials who are middle-aged white guys. They don’t want to say the wrong thing, or take the lead, and I’m totally cool with that. I fully understand. But the whole time nothing was being said I was texting Wes Morgan [Leicester City’s captain]. I’m hot-headed so I was like: ‘I’m going in here. Will you follow me?’ He was like: ‘Yeah, no probs.’ I called it a ‘rant’ but really it was an articulated discussion of why we needed to do something.”

Séamus Coleman, of Everton, was the first captain to offer his support. Kevin De Bruyne then said: “I’m with Troy.” Jordan Henderson echoed those simple words. “That gave me immense pride,” Deeney says. “I’ve been in loads of meetings since then and progress is being made. Is it as fast as I would like? Of course not.”

Deeney suggests that some footballers are so fed up with racist abuse that they are “close to boiling point. I don’t want to say black footballers because lots of white footballers are socially aware. The dressing-room conversation has completely changed. Ten years ago it was football, horses, poker, the generic stuff. Now the conversation can be about Sarah Everard, racism or the political situation in Germany. We’re talking about real stuff at last.”

Are we close to a situation where a football team might walk off the pitch in the middle of a match marred by racial abuse? “I honestly believe so. I think someone like Romelu Lukaku would do it. This might sound strange but look at Colin Kaepernick. He started the most significant peaceful protest in a long time by taking the knee. He was ostracised but look at how successful he’s become off the back of it. So if a really big footballer walked off? Wow, that would be really powerful. I saw Marcos Alonso saying he’s not taking the knee because it’s losing its power. That’s a fair comment. Why is it losing its power? Because nothing is really changing on social media. I get eight or nine [racial insults] a day. Let me get up one when I was having a little rant online.”

Deeney reaches for his phone and finds the tweet. “It says: ‘You’re a black cunt.’ Comes from a man called Sam. Anton Ferdinand and I and a few others were in talks with Twitter about how can we not have verification of users? We need Covid passports, and ID to buy cigarettes or alcohol. But you can go online, racially abuse someone, delete that account, make another one, do the same thing again and go, boom, boom, boom. Social media platforms are getting away with it.

“Twitter say they’re only providing the platform and they can’t control what is said between me and some guy called Sam. I find that baffling. I’ve been called a nigger and a black cunt on there and they say they can’t change those words. But if you say Covid isn’t real on Instagram it comes up as a factfinder. It would show everybody my statement is false. There is a little toolbar at the bottom you can click on which gives you more informed advice on Covid. But ask them to take down the words nigger and black cunt, and call it abusive hate crime? That’s too difficult for them to do. I call bullshit on it.”

Deeney is rightly passionate but he is also amusing and calm. “I’m getting there. I hope all this is a step forward to understanding I have a purpose in life, not just as a footballer. Hopefully conversations like these will move the needle forward and also give people a better understanding of who I am.”

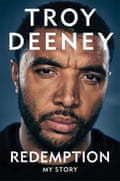

Redemption by Troy Deeney is published by Hamlyn www.octopusbooks.co.uk