Warning: beyond this point, spoilers reign

Shutter Island is no impenetrable art-house enigma: it's an old-fashioned noirish thriller that ends with a massive plot twist. As such, you might have thought it would have been easy to understand. In fact, since the film was released in March, the blogosphere's been awash with debate about what actually happens in the final scene.

Martin Scorsese's film is based on a best-selling novel by Dennis Lehane. The book's protagonist, Teddy Daniels, who's apparently a US marshal, turns out to be Andrew Laeddis, a demented killer. He's a patient in a mental hospital who's been encouraged by his psychiatrist to act out his delusion in the hope that this will dispel it. The role play fails: after a brief recovery, Andrew relapses into insanity and is therefore taken off to be lobotomised.

The film's been described as faithful to the book, and many cinemagoers seem to have assumed that it's telling the same story. Leonardo DiCaprio's Teddy does indeed turn out to be Andrew. However, before he falls into the clutches of the lobotomists, he utters a line that isn't in the book. "This place makes me wonder," he asks, "which would be worse – to live as a monster, or to die as a good man?"

For some, this is to be seen as no more than the rambling of a madman. Others, however, take it as meaning that Andrew's only faking his relapse. His unusual treatment's made him aware of the terrible thing he's done: guilt has therefore engulfed him, and he's deliberately getting himself lobotomised to escape it.

These two versions of what the film means could hardly be more at odds. Yet Scorsese hasn't chosen to indicate which is the right one. Nor has DiCaprio. Perhaps the latter isn't sure himself. He found his role traumatising, and told an interviewer: "I remember saying to Marty, 'I have no idea where I am or what I'm doing.'"

Lehane is credited as one of the film's executive producers, so you might think he at least would know what's going on. Sadly, even he doesn't seem wholly certain: he explains that he stayed out of the scripting process. When pushed, he tries to reconcile DiCaprio's gnomic inquiry with his own original story. "Personally, I think he has a momentary flash," he suggests. "To me that's all it is. It's just one moment of sanity mixed in the midst of all the other delusions."

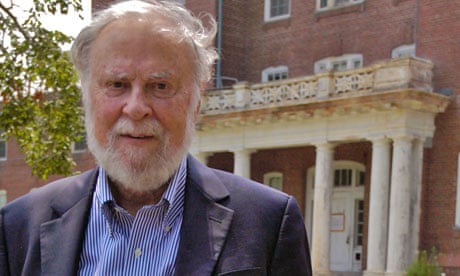

As it happens, just how to end the film was much debated by those more directly involved. One of these was Scorsese's psychiatric adviser, Professor James Gilligan of New York University. On a visit to the location where most of the film was shot, the now-abandoned Medfield state hospital in Massachusetts, I asked the professor what was really supposed to be happening. His answer was clear cut.

Andrew does indeed choose his fate. According to Gilligan, those cryptic last words mean: "I feel too guilty to go on living. I'm not going to actually commit suicide, but I'm going to vicariously commit suicide by handing myself over to these people who're going to lobotomise me." Gilligan says that people who kill others in the way Andrew has don't realise what they're doing at the time. If treatment returns them to their senses, guilt may then overwhelm them.

For Gilligan, the correct reading is important. Shutter Island is set in the 1950s. During that era, severe mental disturbances were often dealt with physically. In America, more than 40,000 patients were lobotomised over a 30-year period. However, progressives were pushing for the replacement of such methods by less ruinous remedies. Andrew's doctor (played by Ben Kingsley) is one of these. His role-play experiment is a test case. If it works, non-invasive treatment will have proved itself. If it fails, the lobotomists' position will be reinforced.

This debate shows some signs of being rekindled: growing understanding of brain physiology is reawakening interest in tinkering with its workings. Gilligan, however, is firmly opposed to this trend, and keen to see psychosocial treatments defended. Shutter Island the book shows such a treatment failing. The film, according to Gilligan, shows it succeeding, at least in dispelling delusion.

A second look at the film suggests that Gilligan's reading must be right. In his final murmurings, DiCaprio is clearly trying to act as if he's acting. After uttering that last line, he leaps up and strides purposefully into the midst of the waiting lobotomists; they don't have to jump him. So why all the mystery? Why weren't things just made a little bit clearer?

Perhaps we can guess. According to Gilligan, "Martin Scorsese said this film will make double the income because people will have to see it a second time to understand what happened the first time." So Marty at least may have known what he was doing. Shutter Island has already become his highest-grossing picture to date.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion