The Legend Of John Henry Explained

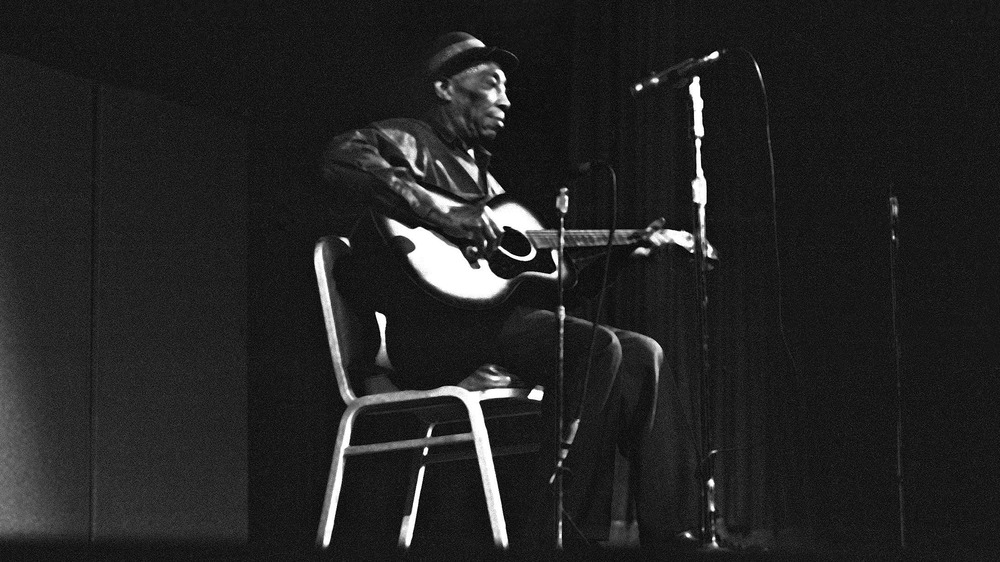

Whether you know the story of John Henry or not, you've almost certainly heard people sing about him. That is because his folkloric tale has captured the imaginations of artists, particularly musicians, for nearly 100 years, and the legend has come to be the subject matter of songs performed by such luminaries as Harry Belafonte, Mississippi John Hurt (pictured above), Van Morrison, Woody Guthrie, Bruce Springsteen, and Johnny Cash, among scores of others.

According to Songfacts, the root of John Henry's popularity as a cultural figure can be traced to a single 1929 book by author and historian Guy Benton Johnson, which contained the earliest known version of the traditional 12-verse work song titled "John Henry, Steel Driving Man," which has served as a blueprint for the multitude of versions released since. The song begins:

John Henry was a railroad man, / He worked from six 'till five, / "Raise 'em up bullies and let 'em drop down, / I'll beat you to the bottom or die."

Johnson believed that this set of lyrics, arranged in 1900, represents the song as it was sung in work camps and on chain gangs as early as the 1870s. Since then, the song has transformed considerably; a 2020 version by Steve Earle (found on YouTube) starts:

John Henry was a steel drivin' man / He died in West Virginia / With his hammer in his hand

Yet the song remains true to the basic story, which continues to resonate with audiences today.

The story of John Henry

Often performed under the title "Steel Driver Blues" or "Spike Driver Blues" (on YouTube), the legend of John Henry concerns a powerful and highly talented Black railroad worker, an ex-slave whose task — steel-driving — was to force deep holes into the ground using enormous steel "spikes," for the deployment of explosives, clearing land for the building of railways. One man, known as the "shaker," would hold the spike in place while a steel driver such as John Henry would strike the spike with enormous power, using a huge metal hammer.

Henry's story is said to have taken place in the 1870s at Big Bend Mountain near Talcott, West Virginia, where the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was under construction, employing thousands of workers in the dangerous work of drilling and blasting to clear a path for a new railway bed, according to the National Park Service.

Working by hand was slow and arduous, even with workers like Henry, who was said to enjoy exceptional stamina as well as immense strength. To speed up work on the tunnel, which was to cut straight through Big Bend Mountain, the railway company bought a cutting-edge steam-powered drill, effectively rendering steel drivers redundant. Legend has it that John Henry was convinced he could out-drill the machine: "If I can't beat this steam drill down, I'll die with this hammer in my hand!"

John Henry's tragic victory

The stage was set for an epic man-versus-machine battle that would reverberate through American folklore for 150 years. According to the historian Carlene Hempel, John Henry, the best and fastest of the thousand workers on the C&O Railway, took up two hammers in an attempt to prove the enduring value of the human labor of himself and his fellow steel drivers. In a steel-driving race against the machine, it is said that Henry managed to drill 14 feet into the stone, five feet more than the machine. The exhaustion of the feat was too much, however, and Henry died on the spot, hammer in hand.

Whether the legend of John Henry is true has been much debated. According to History News Network, many historians agree he was a real man, but that the circumstances of his death may be fictitious, or conflated with that of another figure. The story is a simple one, but as a "symbol of the worker's foredoomed struggle against the machine and of the Black man's tragic subjugation to and defiance of white oppression," as Britannica describes it, its enduring afterlife is not surprising. As a Black American folk hero, John Henry became an icon of the Civil Rights Movement, and even today his story's universal themes resonate, as the automation of work and the ubiquity of technology raise questions about the value of human labor and what is inevitably lost with the march of technological progress.