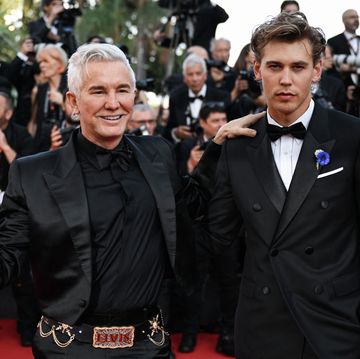

I can guarantee every American high schooler watched a *cool* Shakespeare adaptation—something like 10 Things I Hate About You or She’s The Man—at some point in a high school English class. 400 years after the big man wrote his last play, we still get new Shakespeare adaptations every year, from the stylized (Baz Luhrman’s Romeo + Juliet), to the weird (BBC’s 2010 version of Macbeth, demon-nurses included).

The newest entry is The King—which is based on Shakespeare's historical plays Henry IV, Part I and Part II, and Henry V—starring Timothée Chalamet and Joel Edgerton. In the film, Chalamet plays Young Prince Hal, who shirks his duties and spends a lot of time sleeping when he isn’t pissing off his dad. When he must unexpectedly take the throne, Hal transforms into Henry V, second king of the House of Lancaster. Maturity and military ambition take over and Chalamet leads the character from hungover teen to idol of his country.But as with most tries at the great Shakes canon, not everything in The King matches up with how the Henries of England lived in real life. Here we’ve rounded up what’s true and what’s legend in this battle epic.

That Haircut

Let’s address the elephant in the room: The bowl cut seen round the world. When Chalamet debuted his drastic ‘do on the red carpet, hearts broke for his lost curls. Turns out, the style is historically accurate, and we all know how far Timmy’ll go to uphold the integrity of a role (peaches included). According to hair designer Alessandro Bertolazzi, Chalamet wasn’t too happy about the cut, but Henry V did in fact wear his hair like that. The short cropped bowl with shaved sides was popular amongst men paying homage to monks and priests, and Henry V was one of the first English kings to sport the look.

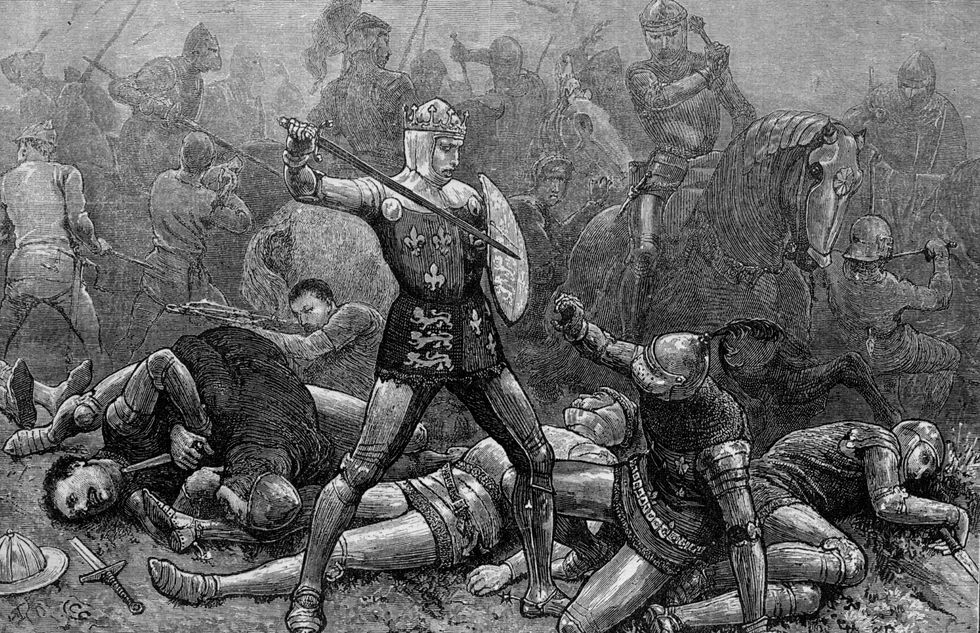

Battle of Agincourt

The main (and possibly horniest) conflict in The King comes to a head with the Battle of Agincourt. Chalamet’s king soldier finally acquiesces to aggression in a war he didn’t want. But with rain, terrain, and the English longbow on their side, eventually the young king rolls around and wins in muddy hand-to-hand combat. In reality, the battle went similarly. English archers picked off French horsemen from a distance, and then footsoldiers fought the men floundering in the mud. One key difference remains: Henry V did not begrudgingly go to war, but wanted French land even beyond any reasonable claim from the past. Maybe Shakespeare and Netflix wanted English propaganda, or maybe nobody could believe such greed of our adored Timmy.

Good Ol’ Falstaff

Joel Edgerton’s character in The King is Falstaff, Hal’s drinking buddy turned advisor. He’s an old war hero who doesn’t parse words, and spends the first half of the film drunk and/or arguing about alcohol. His strategic knowledge and heroic sacrifice directly lead to victory, and he even does a little Jon Snow “Battle of the Bastards” bloody crowd surfing when trying to get a breath of fresh air amongst all the muddy metal. Then Henry cries next to his corpse á la Call Me By Your Name. Taken from Shakespeare’s plays, Falstaff was actually a character of comedic relief. Edgerton, who wrote the screenplay and acted the role, turns Falstaff from clown to trusted companion with an emotional relationship to Henry.

Execution of Prisoners

A watershed moment in the development of Hal to Henry V in The King is his decision to execute all of his prisoners. Falstaff tells Hal not to kill the French prisoners, that he “isn’t that man,” and so the king holds off. As soon as Falstaff dies and the battle is over, Henry tells his men to kill all the prisoners anyway. Chalamet really sold the part—his enraged screeches, howls, and shouts deserve a montage of their own. After the actual Battle of Agincourt, the real Henry V gave the same order to staunch any second wind of French rebellions. But, ever the classists, the English allowed high-ranking prisoners to live.

He Loved God

After the transition from playboy to serious monarch (a.k.a., handsome hair to bowl cut) Hal is shown praying with some rosary beads. Hal also scoffs at the idea that England will fight and colonize all the way from France to Jerusalem. How dare they trample the Holy Land, Chalamet’s scrunched eyebrows protest. Outside of Hollywood, six centuries ago, the real Henry V was very religious, both in hairstyle and ambition. On his deathbed he even stated his intention to take the Hundred Years’ War all the way to Jerusalem.

France's Lady Catherine

After the English beat Robert Pattinson’s goofy dauphin in perhaps the most pathetic death scene ever filmed, the king of France offers land and his daughter Catherine de Valois to the king. No tears are shed for her brother’s muddy, embarrassing corpse! Played by Chalamet’s real life partner, Lily-Rose Depp, Catherine speaks in only two scenes, but makes the most of them. Back in England with Henry, she pretends not to know English when he commands her to use it instead of French, but then speaks it fluently. This sassy moment from Catherine alludes to both fact and folklore. Back in the 1400s, Henry V was the first English king to read and write vernacular English well enough to integrate it into court customs. In Shakespeare’s Henry V, Catherine learns English from her handmaid in preparation for her marriage to the English king.

The Accidental King

Viewers are led to believe that Hal never expected to become king, and thus didn’t act the part. He is pegged as just a party boy his father couldn’t trust. Even his new wife mocks him as just the son of a usurper, questioning his authority and claim to England, let alone France. In reality, Henry V was known for his youthful debauchery just as much as his aggressive military aspirations. And, Catherine was right after all—in 1399 Henry’s father, Henry IV, deposed his cousin Richard II on the grounds of tyranny and a claim to the crown through his maternal grandfather, Edward III.