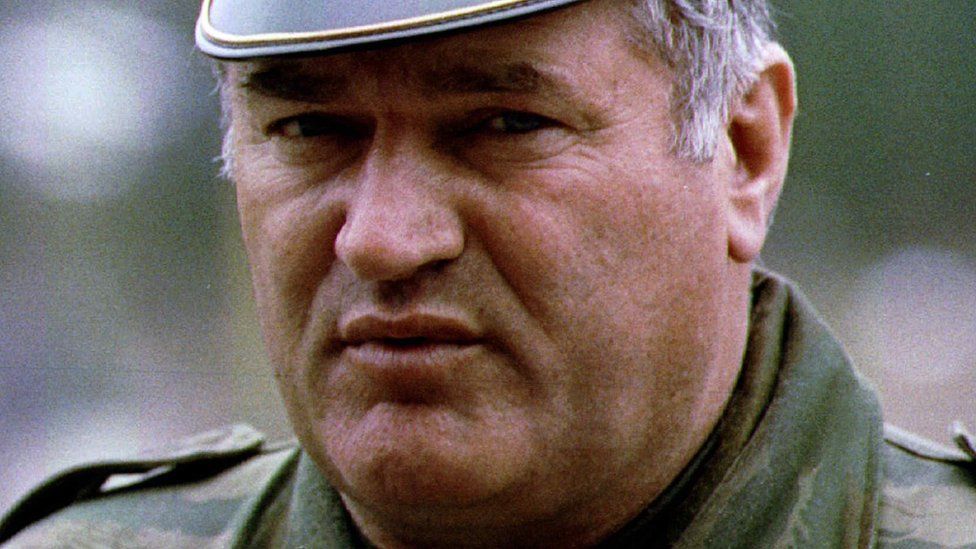

Ratko Mladic, the 'Butcher of Bosnia'

- Published

Ratko Mladic was the army general who became known as the "Butcher of Bosnia", who waged a brutal campaign during the Bosnian war and was jailed for life for directing his troops in the worst atrocities in post-war Europe.

More than 20 years after he was first indicted by an international war crimes tribunal, and a year after the closing arguments in his case, Mladic appeared in court at The Hague on Wednesday to hear the verdict against him.

In typical style, he railed against the judge and insulted the court and he was removed from the room. In his absence, he was convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity.

Seemingly ever-present on the front lines and respected by his soldiers as a man of courage, Mladic oversaw an army of 180,000 men during the Bosnian war of the 1990s.

In 1992, Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks) and Croats voted for independence in a referendum boycotted by Serbs. The country descended into war, Bosniaks and Croats on one side and Bosnian Serbs on the other.

Along with the Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadzic, Mladic came to symbolise a Serb campaign of ethnic cleansing that left tens of thousands dead and hundreds of thousands displaced.

The worst and most enduring crimes pinned on the former army chief and his men were an unrelenting three-year siege of Sarajevo that claimed more than 10,000 lives, and the massacre at Srebrenica, where more than 7,000 Bosniak men and boys were slaughtered and dumped in mass graves.

"The soil here is soaked with blood" - survivor Mevludin Oric

When the conflict came to an end in 1995, Mladic, facing an indictment for war crimes, went on the run.

With considerable help, he evaded capture for 16 years, until May 2011 when police descended on an unassuming yellow brick house in the village of Lazarevo, north of Belgrade.

Clad in black clothes and black masks, officers surrounded the house. Inside, Europe's most-wanted man - older in appearance than his 69 years and thinner than the bull-like general of his war days - was preparing to go for a walk in the garden.

Ratko Mladic was ferocious in pursuit of what he saw as the destiny of the Serb nation. He saw the war as an opportunity to avenge five centuries of occupation by Muslim Turks. He would refer to Bosniaks as "Turks" in order to insult them.

There may have also been an emotional root to his ruthlessness. In 1995, a year before the massacre at Srebrenica, his much-loved daughter Ana, a medical student, shot herself with his pistol - an act that, according to people close to him, hardened his character.

Some believe she chose to die after learning of atrocities committed by forces under her father's command.

Mladic was born in the south Bosnian village of Kalinovik. On his second birthday, in 1945, his father died fighting pro-Nazi Croatian Ustasha troops.

He grew up in Tito's Yugoslavia and became a regular officer in the Yugoslav People's Army. A career soldier, he was said to inspire passionate devotion among his soldiers.

When the country slid into war in 1991, Mladic was posted to lead the Yugoslav Army 9th Corps against Croatian forces at Knin. The following year he was appointed to lead a new Bosnian Serb army.

As his gunners pounded the city of Sarajevo in early 1992, mercilessly killing civilians, he would yell "Burn their brains!" to encourage them, and "Shell them until they're on the edge of madness!"

The siege laid waste to parts of central Sarajevo, hollowing out houses and charring cars. A long stretch of road leading into the city became known as "sniper's alley", after the Serb marksmen who would fire at anything that moved: car, man, woman or child.

Massacre at Srebrenica

The most horrific crime of which Mladic was convicted happened 80km (50 miles) north of Sarajevo, in a small salt-mining town whose name would become indelibly associated with the horror of that week.

Srebrenica was a Bosniak enclave under UN protection, when in July 1995 Mladic's forces overran it and rounded up thousands of men and boys aged between 12 and 77.

As the men were detained, Mladic was seen handing out sweets to Bosniak children in the main square. Hours later, in a field outside the town, his men began shooting.

Over the next five days, more than 7,000 men and boys were executed, reportedly machine-gunned in groups of 10 before being buried by bulldozer in mass graves. It was the worst mass execution since the crimes of the Nazis.

The war ended later that year. Hundreds of thousands of non-Serbs had been driven from their homes in an attempt to create an ethnically pure Serb state in Croatia and Bosnia.

In late 1995, a UN war crimes tribunal indicted Mladic on two counts of genocide, for the Sarajevo siege and the Srebrenica massacre. Many other combatants, including Croats and Bosniaks, were also accused of war crimes. Mladic went on the run, but he didn't go far.

Flight and arrest

As a fugitive Mladic still enjoyed the open support and protection of the then-Yugoslav President, Slobodan Milosevic. He returned to Belgrade, where he went untroubled to busy restaurants, football matches and horse races, escorted by bodyguards.

But Milosevic's fall from power in 2000 and subsequent arrest put Mladic at risk. He spent the next decade moving through hideouts in Serbia, relying on a diminishing band of helpers.

In October 2004, his former aides began surrendering to the war crimes tribunal, as Serbia came under intense international pressure to co-operate.

When Karadzic was detained in Belgrade in July 2008, speculation grew that Mladic's arrest would follow. But it was not until 26 May 2011 that police units descended on Lazarevo and surrounded Mladic's yellow brick house.

When the officers moved in, the man who had vowed to never be taken alive surrendered quietly, and the two loaded guns he kept for protection lay untouched. He was 69 and had already suffered a stroke, partly paralysing his right arm.

"I could have killed 10 of you if I wanted, but I didn't want to," he reportedly told the officers. "You're just young men, doing your job."

Brought to justice

He finally went on trial in 2012, at The Hague, facing 11 charges including genocide. The court, anxious that he should not die before the end of the proceedings, scaled back the case against him.

He was in poor health, and had difficulty moving, apparently due to a series of strokes. "I'm very old. Every day I'm more infirm and weaker," he told the court.

Despite his frailty, Mladic was defiant in court. He sarcastically applauded the judges as they entered, and argued vociferously with them. Catching the eye of a Bosnian woman who had gestured rudely to him, he drew his finger across his throat.

His 12-member defence team argued that their client was an honest, professional career soldier who successfully defended Bosnian Serbs from the threat of genocide.

They said he was in Belgrade for meetings with international officials when most of the killings in Srebrenica took place, and that he had no means of communication with the men there. The prosecution did not disagree, but contended that he met senior deputies before leaving the town, and gave them the order to kill.

The defendant branded the court proceedings "satanic".

Fanatical and fearless, Mladic became a folk hero to many of those he led, and he remains a hero to many in his home village of Bozanovici, where a sign nailed to tree still reads "General Mladic Street".

Two decades on from the war, in a courtroom at the Hague, he was diminished physically but not in temper. Just as in his other court appearances, he shouted and disrupted the court. But it did not matter. He was removed, and his sentence handed down in his absence.