Buy

Resources

Entertainment

Magazine

Community

As the decade of the 1960s opened up, Studebaker-Packard appeared for once to be in pretty good shape. After losing money steadily since 1954, the company recorded its largest profit ever in 1959, some $28.5 million, while boasting calendar-year production of 153,823 cars and 7,737 trucks. This surprising success was the result of introducing its new Lark compact. So, heading into 1960, Studebaker seemed to have the right momentum.

The company’s passenger-car range was limited to just the Lark series and the aging Hawk coupe. The truck model lineup also was not extensive, but for 1960 it offered plenty that was new. Studebaker’s basic truck cab had been in production since the 1949 model year and was looking rather dated by 1960. To correct this problem, the company introduced more modern-looking ½- and ¾-ton models with a new cab derived from the Lark passenger car sheetmetal. The new Champ 5E series featured a simpler, more rugged-looking four-bar grille and a brawnier front bumper. It was mounted on a truck chassis and was a quite an attractive pickup. The base price of the bottom-line Champ ½-ton was $1,875, a bit of a hike from the prior year’s stripped-down Scotsman pickup, which had been tagged at $1,791. However, the Champ was a better-finished product and looked a lot more expensive. The Scotsman had been not much more than a drab price leader.

The new Champs rode the same wheelbases as the prior-year light trucks: 112 inches and 122 inches. They carried over the same pickup box as used in prior years, too, a flare-fender design that was becoming slightly old-fashioned. The 1-ton and larger Studebaker trucks, called the Transtar models, continued to use the old C-cab, with its aggressive-looking grille/headlamp fascia. For some reason, the Transtar name had been dropped in 1959, but it reappeared in 1960 on 1-, 1.5-, and 2-ton models. Four-wheel-drive models were offered as well, but only in the heavy-duty C-cab Transtar models, not in the Champ series.

The basic Champ 5E5 pickups were powered by Studebaker’s trusty L-head six-cylinder engine, with 169.6 cu.in. and 90 horsepower. The higher-priced 5E6 ½-ton trucks, along with the 5E11 ¾-ton jobs, got a larger 245.6-cu.in. L-head six, good for 118 hp. The top-line 5E7 and 5E12 models were equipped with Studebaker’s excellent 259-cu.in. V-8, which developed 180 hp in standard two-barrel form, or 195 hp with the optional four-barrel carb. These two models could also be ordered with the optional 289-cu.in. V-8, good for 210 hp with a two-barrel or 225 hp with four-barrel carburetion.

The standard transmission was a three-speed manual with a steering-column-mounted shifter, and synchromesh on second and third gears. A four-speed transmission with floor shifter was optional, as was overdrive. Only the 5E7 and 5E12 models offered the optional Flight-O-Matic transmission. Other optional equipment included the usual truck extras of that era: painted rear bumper, Twin-Traction rear axle, power brakes, dual horns, radio, clock, heater/defroster, right-hand taillamp, side-mounted spare tire, heavy-duty springs and shocks, heavy-duty clutch, Deluxe Cab trim, and so on.

All in all, the new Champs were very competitive trucks that would certainly have sold better if only the company had been able to get them into production earlier. As it was, a combination of problems at the plant, along with a steel strike, delayed production until the spring of 1960. According to Andy Beckman of the Studebaker Museum in South Bend, Indiana, production of Studebaker’s 5E5-5E12 trucks came to 5,602 units. Considering the amount of effort put into freshening the truck line, that had to be a major disappointment for Studebaker management.

The 1961 Studebaker trucks were known as the 6E series. The big news for the Studebaker truck line that year was the introduction of a "new" overhead-valve six-cylinder engine, actually an upgrade of the old 169.6-cu.in. L-head mill. Now producing 110 hp, it was a significant and well-overdue improvement shared with the passenger car line-up. With the OHV six introduction, the company dropped its aging 169.6- and 245-cu.in. L-head sixes from the line. The number of models in the light-truck (½-¾-ton) lineup shrank to six, down two from the prior year.

Also new for 1961 was a "Spaceside" slab-sided pickup box, the tooling for which was bought from Dodge. It was single-wall construction when double-wall was becoming the norm, but it gave Studebaker something new and modern-looking. The new box was wider than the carryover box and stuck out noticeably on the sides. The truck business improved, with production of the 6E5-6E12 models climbing to 6,592 units for 1961.

Beginning with the 1962 models, dubbed the 7E series and introduced in June of 1961, a Detroit Diesel engine was available in 1½- and 2-ton models, and air brakes could be had on the 2-ton units. A 96BBC truck (meaning 96 inches from bumper to back of cab) was available in both gasoline and diesel-powered models, also beginning in 1962. Engineers achieved the short cab length by deleting the fiberglass grille, flattening the front of the hood, and applying a distinctive flat-nose grille below the hood. This model was produced in response to motor vehicle laws in certain states that restricted the overall length of tractor trailers; these Studebaker modifications permitted the use of longer trailers. Also, for 1962, the Champ six-cylinder trucks could be ordered with the optional automatic transmission.

The 1962 7E5-7E12 model production rose to 7,325 trucks, Studebaker’s highest level in years. The company had worked hard to modernize the truck line and also offered the lowest-priced pickup on the market, but it was plain that Studebaker’s dealers weren’t expending enough effort selling them; considering the size of the dealer network, the totals should have been much higher. The fact that Studebaker’s union went on strike again that year certainly didn’t help. It deprived dealers and the company of needed product and caused buyers to lose confidence in Studebaker.

For the 1963 model year the 8E series boasted a host of improvements and upgrades. The steering geometry was all-new and a new type of constant-ratio steering gear was adopted. Front shock absorbers were now mounted in "sea-leg" fashion, for better cornering, and brake and clutch pedals were now the suspended type. The brake master cylinder was moved to the firewall; it had been frame mounted previously. Improved front springs were featured, as were full-flow oil filters, now as standard equipment. Six-cylinder engines got an improved carburetor. The old fender-style pickup box was discontinued. Air conditioning was now available, along with a new "Conestoga" camper shell. Production fell to 5,861 trucks.

The 8E series carried over for 1964. New Service Champ models were available, equipped with fiberglass utility bodies for plumbers, electricians, and the like. Studebaker had one other new truck model for 1964: the Zip Van, a compact stand/drive model on an 85-inch wheelbase, sold only to the U.S. Post Office for delivery service. Studebaker won a contract to produce 4,238 of these sturdy little right-hand-steering units under a $9 million contract, which was big by Studebaker standards. The Zip Van utilized the Champ’s six-cylinder engine hooked up to a three-speed automatic transmission, and was fitted with a Champ radiator, front axle and springs, brakes, and wheels. Bodies were produced by Met-Pro, Inc. of Lansdale, Pennsylvania.

Due to the December 1963 shutdown of South Bend production, only 2,509 model 8E5-8E12 models were built.

Studebaker also produced a line of 2½- and 5-ton trucks for the U.S. Army. After South Bend closed, the company transferred the military truck contract to Kaiser Jeep Corporation, which also bought the Mishawaka, Indiana plant they were assembled in. That unit formed the nucleus for what would later become AM General Corporation, which today is the world’s largest producer of tactical wheeled vehicles. There’s justice in that.

Recent

Muscle Cars

All Five Factory-Sold Red, White and Blue AMC Performance Cars, Collected Under One Roof

Photo: Jeff Koch

By the mid-’60s, the muscle car wars raged ever onward. Every year brought hotter powertrains, better traction, wilder style—all at a price that even the local grocery-store bag boy could afford. Winners and losers were determined between the lights. Everyone seemed to want to get in on the action.

Everyone, that is, except for poor AMC. Formed by merging Nash and Hudson in 1954, AMC was small and cautious, chasing reliability and economy over trends. But Detroit overwhelmed Rambler’s compact-car raison d’etre, and by 1966 sales were in freefall. Cautious old management was replaced by Roy Chapin, Jr., a CEO who sought to capitalize on America’s performance awakening; Chapin’s family founded Hudson Motors, whose Twin-H-Power Hornet dominated early NASCAR tracks. He understood that racing would attract a newer, younger clientele.

A variety of crucial pieces to the company’s high-performance puzzle were either on-line or coming soon. A new 290-cube V-8 engine launched mid-1966; a bored-and-stroked 315-horse, 390-cube version would arrive in ’68; the upcoming two-seat 1968 AMX and its Javelin pony car counterpart looked promising. Chapin’s team worked to put it all together, mix in a dose of American pride and wink-wink psychedelia, and mount a sales campaign designed to make AMC sexier. Red, white, and blue (RWB) became the company’s signature high-performance palette.

The push started early as Javelins signed up for the SCCA’s Trans-Am road racing series. A black-and-white February ’68 sales bulletin showed pictures of the RWB scheme on a Javelin, days before it debuted at Daytona, and provided Rinshed-Mason and Sherwin-Williams paint codes for dealers to paint their cars. “When you see the cars in person or see color pictures, we think you will agree that the color scheme really looks like a winner!” A string of second place finishes (at War Bonnet, Bridgehampton, Meadowdale, St. Jovite, Bryar Park, and Riverside) were seen as moral victories from a team that had a fraction of the budget that the competition played with. Also, Craig Breedlove’s record-setting RWB Javelins and AMXs helped reinforce the concept in November of ’68. These helped cement the tri-color scheme in car buyers’ minds as the year progressed.

The most outrageous of the factory-painted RWB models to break cover was the 1969 Super Stock AMX. As AMC sought to hype its new performance outlook, Hurst Performance Research’s George Hurst and Doc Watson sought to follow up on the group’s successful Hemi Mopar A-body project for ’68. Plans fell together quickly, and by February of ’69, AMC introduced its SS/AMX to the Southern California Dealers Association meeting at Riverside, where hot-shoe Shirley Shahan—newly signed to AMC—made some demo runs. (She would go on to set a new SS/D record in her AMX that year.) NHRA also mandated a minimum of 50 cars to be built; AMC ended up building 52. All were delivered to Hurst as Frost White 390/four-speed cars, with 4.44:1 gears. While rebuilding the AMXs for racing, including going into the engine, Hurst took care of the RWB paint if the ordering dealer so specified, for a $79 surcharge. The restored "American Dream", the last to be built, was a factory RWB SS/AMX; it was shipped to Anchorage, Alaska, and lived a surprising life - much of it shielded from the elements in a storage container. In its day, it ran consistent 10.50s in the cool Alaskan air.

The SS/AMX was designed to be a strip-only monster, but the 1969 SC/Rambler was arguably AMC’s most visible (and notorious) muscle car for the street. It was developed simultaneously with the SS/AMX. Keep in mind: the usual muscle car formula placed a full-size-car engine in a mid-sized body; AMC went a step further and put its biggest engine in its compact-car line. You could compare the compact Dodge Dart with either the 383 or the rare ’69-only 440 option, or maybe the big-block Chevy II Nova, but the Rambler was by far the most minimalist platform of the bunch. Built on the AMC Rambler Rogue hardtop, which was ending production to make way for the upcoming Hornet, the SC/Rambler was essentially a parts-bin special. AMC’s big 390-cube V-8 led the charge, with all cars receiving a Borg-Warner Super T-10 four-speed with Hurst shifter, 3.54 gears with Twin-Grip diff, an AMX-spec suspension package, heavy-duty cooling, a Sun tach strapped to the steering column, dual exhaust with glass-packs, charcoal interior with RWB headrests, blue painted styled steel wheels, Hurst badging, and more. The only option was a radio—but who could hear it over the glass-packs?

Photo: Jeff Koch

<p>SC/Ramblers were available in two different RWB color schemes: the "A" scheme (foreground) and the "B" scheme.</p>

Though Hurst gets credit for design and marketing, and received $200 per car for their efforts, SC/Ramblers were built on the Kenosha line. Most were white with red sides and a blue over-the-top stripe, with the scoop receiving bold “AIR” lettering and engine displacement callouts. AMC advertised a 14.3-second quarter-mile time—unheard-of in its day—although some press venues got their examples to go even quicker. All for $2,998 at your local AMC store.

Not all AMC dealers received a SC/Rambler; some suggested that if the graphics were toned down, they could probably sell one; at the same time, AMX production slowed to a point where an extra thousand 390s were lying around. Management solved this by extending SC/Rambler production. All of the mechanical bits remained, but the revised application of color included blue rockers, with the red side element reduced to a simple stripe. This became known as the “B-scheme,” with the red-side models retroactively dubbed “A-scheme” by enthusiasts. The B-scheme cars did without the hood/roof/trunk stripe. A total of 1,512 SC/Ramblers were built, with A-scheme examples produced 3:1 over the B-scheme.

With the Rogue making way for the Hornet in 1970, AMC once again turned to Hurst to develop a special model. Their answer: the 1970 Rebel “The Machine” (known also simply as the Rebel Machine), based on AMC’s mid-sized coupe. Beyond the RWB paint scheme, with blue rockers and hood/scoop plus a body-length red stripe, there was an RWB lower grille detail, functional hood scoop with integrated 8,000-rpm tach, and stamped-steel 15-inch Kelsey-Hayes wheels. A suite of engine improvements saw the power rating jump to 340 horses. All Machines featured bucket seats, a floor shifter, 3.54 gears, and dual exhaust that had proper mufflers.

But the Machine was also available with optional creature comforts: automatic transmission, A/C, power steering, and a vinyl top were on offer. Soon after production started, AMC allowed Machines to be painted other factory colors; doing so deleted the red and blue striping. It sounded like what the market wanted, but in a world of Hemi Mopars, Super Cobra Jet Torinos, and 450-horse LS6 Chevelles, the Machine was on its back foot from the start. Just 1,936 were made, roughly half in the signature RWB scheme seen here. Like the SC/Rambler before it, and the Hornet SC/360 (never available in RWB from the factory) after it, the Rebel Machine became a one-year-only proposition.

There was one other limited-run RWB AMC that Hurst had no hand in creating: the Trans-Am Javelin. While drag racing was a healthy part of AMC’s performance-car expansion into 1970, the road-racing crew at the SCCA were generating their own excitement. The Trans-Am series primarily starred American pony cars in the Over Two Liter class; with Mustangs, Cougars, Camaros, and more racing fender-to-fender, Trans-Am saw some of the most exciting racing of the era—and the Javelin would be in the thick of things from the get-go. AMC elected to build 100 RWB T/A Javelins to resemble the competition cars, and gave them the gumption to back up their brash looks: a ram-air-induction 390 fed by a scooped hood cribbed from the AMX, Hurst-shifted Borg-Warner T-10 four-speed, 3.91 gears with Twin-Grip, F70-14 tires on Magnum 500s, heavy-duty suspension and cooling, a 140-mph speedo, 8,000-rpm tach, high-level SST interior trim, plus custom-engineered front and rear spoilers.

Unlike Detroit’s hot small-block pony cars, the T/A Javelin wasn’t a homologation piece - just a low-production eyeball-grabber for select dealers. It was well-timed: though Ford dominated the season, AMC won three of the 11 Trans-Am events (at Bridgehampton, Road America, and Circuit Mont-Tremblant) with Mark Donohue piloting Roger Penske’s Javelin to the winner’s circle. The wheels seen here are Trans Am Race Engineering Superlites; while they’re not factory-correct, they are period-look reproductions of what the Trans-Am racers would have used.

Each of these five are powerful, limited-run muscle cars built by the lowest-production American manufacturer extant. Finding any one of them is difficult enough - production was low, the survival rate was lower, and not every model line was painted RWB exclusively. But all five? And ensuring that each was painted in AMC’s signature scheme by its builders? All, in one place, at one time? In one collection?

Photo: Jeff Koch

Dan Curtis, owner of the five RWB warriors pictured here, owns AZ AMC Restorations in Peoria, Arizona. The shop has been a full-time endeavor for about a dozen years, but Dan’s love for AMCs dates back to the ’68 390 four-speed AMX he street-raced in Massachusetts as far back as 1971. He confesses that he initially dismissed the whole RWB concept as “silly,” but has held on to an A-scheme SC/Rambler since the late ’90s. Dan claims he never sought the RWBs out, but rather accumulated them over time - almost accidentally. The B-scheme SC/Rambler was purchased from noted AMC authority Mark Fletcher, co-author of the Hurst Equipped book, where this example is also pictured. The seeds to obtain the SS/AMX were planted via a chance meeting in 2008, though the car wasn’t offered to Dan for another decade; its RWB status was incidental to it being the final SS/AMX built. Six months later, a friend offered Dan the T/A Javelin in a part-trade offer.

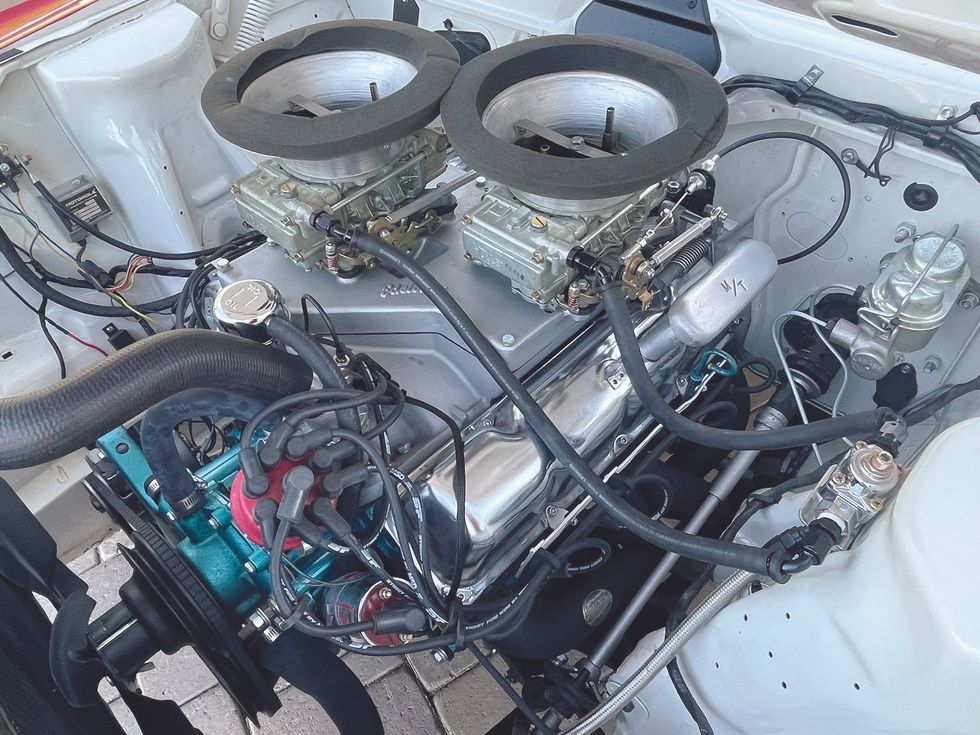

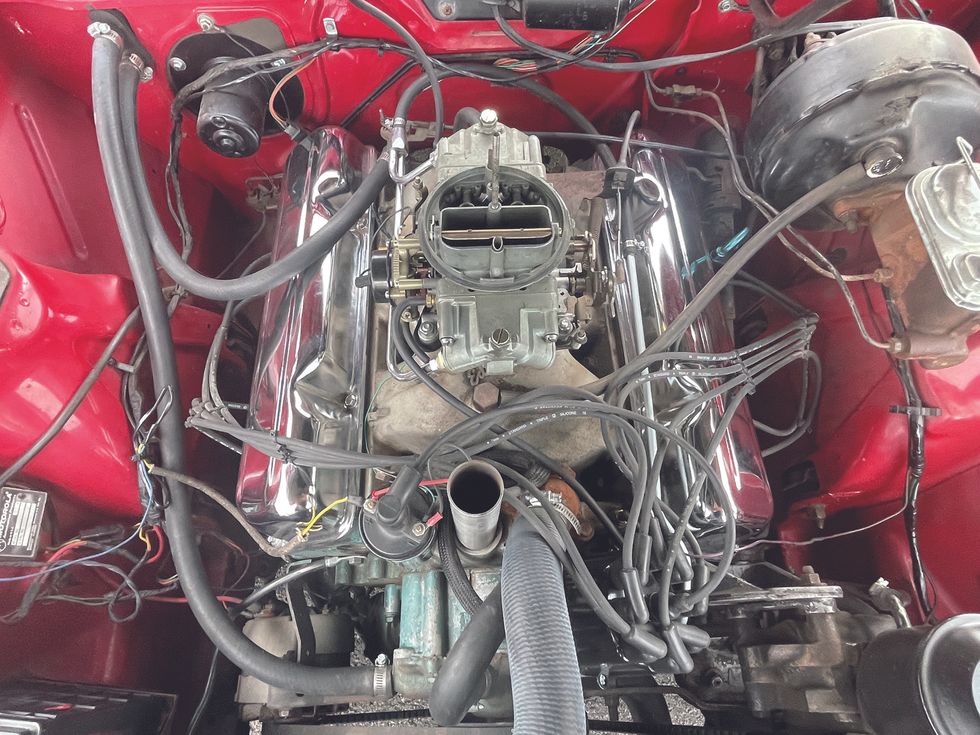

“This was late 2018 or early 2019,” Dan says. Soon, “I realized I had four out of the five - I only needed a Rebel Machine to complete the set. Then this Machine popped up in Las Vegas, and I thought, I can make this happen.” Dan points out that the only time you might see all five RWB cars together (other than on the pages of HMM, of course) would be at a national show - and that’s only if someone brought an SS/AMX. Other than his own, “I’ve never seen all five RWB cars together in a private collection.” All five of the cars seen here have been sorted out by his shop, including the installation of some genuine vintage over-the-counter AMC Group 19 parts under the hoods for a little extra kick. All of them are now ready to drive at a moment’s notice. They are shown regularly—whether singly or together—and Dan is happy to wave the flag for the forgotten and little-seen American muscle car contingency.

Keep reading...Show Less

Photo: Patrick Nichols

In 1967, to the relief of Ralph Nader, Don Yenko was moving away from building Corvair Stingers for SCCA homologation and started buying Camaros as the next product to be modified at the Yenko Sportscars facility in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. Along with partner Dick Harrell, there were 60 Camaros built featuring the now-famous 427-swap into 350-powered, and later 396-powered Chevrolets that year. By 1969, Yenko also had a deal with Chevrolet to perform Yenko modifications on COPO 427 Chevelles and was looking at the Chevy II/Nova.

What Is A Yenko Nova?

Photo: Patrick Nichols

Chevrolet was supplying Yenko with factory 427-equipped Camaros and Chevelles via GM's Central Office Production Order (COPO) program to support Yenko's Super Car program. With Camaro and Chevelle production locked in, Yenko’s next plan was to add the Chevy II/Nova to the lineup. Since Chevrolet did not (some say would not) provide COPO 427-equipped Novas to the dealership, Yenko reverted to the original build plan used on the Camaros and Chevelles: they would order batches of cars from Chevrolet equipped with the L78 396-cu.in. engine and swap in one of two 427-cu.in. engines, depending on if the car had an automatic or four-speed transmission. There was a specific set of color codes for each batch, and each car was ordered with the Super Sport package to get the 396. Once the batches arrived, Yenko would add the rest. Depending on who you ask, there were between 37-40 Yenko Novas built in 1969. Today there are maybe 10 survivors.

Sold By Yenko And Hidden In A Garage

Photo: Patrick Nichols

In 2018, Chevelle authenticator Patrick Nichols received a tip from a stranger that there was an interesting Rallye Green 1969 Nova in White Oak, Pennsylvania, that had been parked in 1978. When Nichols called, the original owner, Dennis Michalo, was on the line with a story about a, L78-equipped Nova that he had purchased from Don Yenko in 1969. According to Michalo, he approached his local dealer in Duquesne, Pennsylvania looking for a base Nova equipped only with a “radio, Posi, and some other minor items.” More importantly, he was looking for an automatic. When he couldn’t find what he wanted, Michalo called Don Yenko in nearby Canonsburg who had a base model sitting on his lot. The Rallye Green 1969 Nova was basic. It had been ordered with the L78 SS396-engine, heavy duty suspension, rubber floor mats instead of carpet, no trim on the outside (except SS badges and hood), hubcaps on green rims, and an automatic transmission. Michalo bought it for $3,050 cash.

Because of the color (79/79 Rallye Green is one of four offered on 1969 Yenko Novas) the 731 black bench-seat interior, the L78 375hp 396 engine, and the date on which it was ordered, the prevailing theory is that this car was ordered by Don Yenko’s dealership in early 1969 as part of a batch of 20-22 cars to be converted to 427-powered Yenko S/C Novas, but was sold instead to Michalo before the job was done. There are other 396-powered Yenko /SC Novas that were sold through Yenko, but no record of any with an automatic. Is this to be considered an unconverted Yenko S/C Nova? Does it fit between the full 427 package of converted Yenco S/C Novas and the 396 four-speed Yenko Nova S/Cs that are out there? The debate is ongoing.

Where Is This Big-Block Nova Now?

Photo: Patrick Nichols

Nicols currently owns the Nova and has it stored in the “exact same condition” as it was found in 2018. Nichols says that he gathered all the parts in a bucket from Michalo’s garage and found the distributor and other parts in the trunk and trailered it to a storage facility located somewhere in Tennessee. Occasionally, he brings it out on a trailer for a cruise or car show, but mostly Nichols is hanging on to its originality.

Photo: Patrick Nichols

If anyone has any information or strong opinions about this automatic Nova sold by Don Yenko, its originals or authenticity, drop a comment below.

Photo: Patrick Nichols

Decoding the Nova's trim tag reveals:

- 02 D is fourth week of Feb 1969

- WRN is the Willow Run, Michigan, plant

- 731 is the base, bench seat, black interior

- 79/79 Rallye Green paint

Keep reading...Show Less

Interested in a new or late model used car?