5 things to know about the Boston murder case at the center of a new Netflix documentary series

Sean Ellis, who was freed after serving 22 years in prison, is the subject of "Trial 4."

Related Links

Sean Ellis was 21 years old when he was convicted for the 1993 murder of Boston Police Det. John Mulligan.

Two mistrials and a third that cemented his lifetime sentence spelled out Ellis’s fate until 2015, when a court ruling reversed his convictions on first-degree murder and armed robbery charges. In 2018, after calls for another trial, charges against Ellis were withdrawn.

Now, Ellis, who spent over 22 years behind bars and whose attorneys had long sought that fourth trial, is telling his story in a new Netflix documentary that hit the streaming service Wednesday, “Trial 4.”

The eight-part series begins with Ellis out on bail.

He has maintained that he is innocent in the grisly crime that unfurled early one morning outside a Walgreens drugstore in Roslindale. The subsequent investigation was helmed by corrupt detectives that some have said may have worked to cover up their own wrongdoings in making a speedy arrest.

But whether Ellis is in prison or not, prosecutors have said he’s their man.

Here’s five things to know about the case and the details surrounding it:

Authorities called the crime ‘a cold-blooded, premeditated murder of a Boston police officer.’ Ellis said he went to the store to buy diapers.

The front page of The Boston Globe, the day after the murder of Boston Police Det. John Mulligan.

Mulligan, a 27-year member of the police department, was shot as he worked a private security detail at a Walgreens drugstore on American Legion Highway in Roslindale early on Sept. 26, 1993.

The 52-year-old detective was over halfway through a midnight-to-6 a.m. shift when first responders received a 911 call for an officer needing assistance around 3:54 a.m. Mulligan was shot four or five times in the front of his head, according to a report in The Boston Globe the following morning.

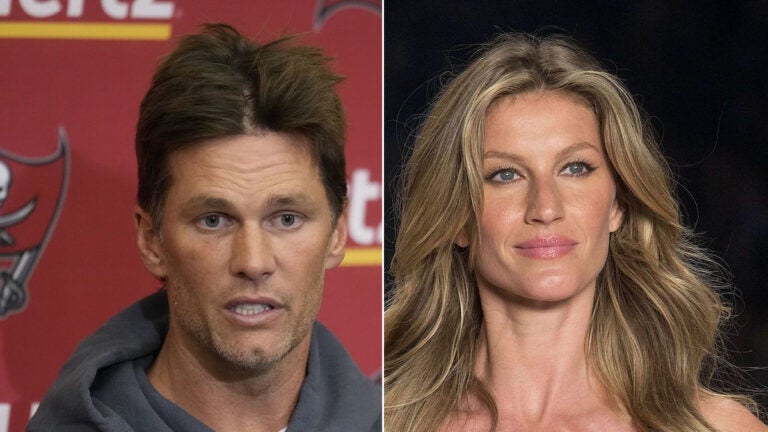

A March 22, 1995, photo of Sean Ellis in Suffolk Superior Court in Boston, during jury selection of his second trial.

Investigators said Mulligan’s department-issued 9mm Glock semiautomatic pistol was missing, although he was shot with a different gun: a .25-caliber weapon.

“This was a cold-blooded, premeditated murder of a Boston police officer,” then-Police Commissioner William J. Bratton told reporters. “There were some elements that would lead one to describe it as execution-style … an assassination.”

Ellis, then a 19-year-old from Dorchester, has said he went to the store to buy diapers. He was with Terry L. Patterson, also 19, of Hyde Park, who was convicted of murder in the case but later had his conviction overturned on appeal, according to the Globe.

Witnesses told authorities they saw Patterson’s Volkswagen Rabbit at the store, and one witness, Rosa Sanchez, told police she saw a man she later identified as Ellis crouched next to Mulligan’s Ford Explorer before shots were fired, the newspaper reported. A forensic examiner initially reported finding Patterson’s fingerprints on the vehicle.

Later, Ellis’s then-girlfriend recalled him retrieving two guns from his home, which he left at her apartment, according to the Globe. She and a friend ultimately left the weapons — Mulligan’s pistol and the firearm he was shot with — in a field where police discovered them.

Over a week after Ellis’s arrest on Oct. 6, 1993, his mother, Mary “Jackie” Ellis, struggled to comprehend how her son was charged in such a horrific crime.

“I wanted my children to follow my example,” she told a Globe reporter. “I wanted them to become involved in their community, in cleaning up their buildings and taking pride in their neighborhood.”

The senior Ellis admitted she had called the police before on her own son. In September 1992, authorities were called after her son allegedly left their house with the child of her then-boyfriend following an argument. Ellis was later charged with assault and battery, family abuse, and threatening to commit a crime and was placed on probation, the Globe reported.

When he was arrested for Mulligan’s murder, his only outstanding charges unrelated to the slaying were for kidnapping and assault and battery with a dangerous weapon — both brought on by a family dispute, according to the newspaper.

Still, she explained, the murder didn’t square right with what she knew about her son.

“I can’t visualize it, even in his deepest anger, that my son would take somebody’s life,” she said.

Ellis’s first two trials in January and March 1995 both resulted in juries voting 9-3 to convict. He was ultimately convicted that September and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

His conviction sat on the theory of “felony murder,” according to the Globe. In other words, because Ellis participated in the robbery of Mulligan, he should be held responsible for his murder.

At the time of his third trial who exactly pulled the trigger and took Mulligan’s life had “never been officially established,” the Globe reported.

Sean Ellis is led from a Boston police station as Homicide Sgt. Det. Charles M. Horsley looks on.

Mulligan apparently loved his job — but was still a ‘problem officer’ for the department.

Mulligan, of West Roxbury, joined the Boston Police Department in 1966 — and apparently loved his job.

Not long after joining the force, Mulligan began working practically around the clock, often picking up overtime shifts and raking in six-figure yearly salaries. After his death, he was remembered for racking up hundreds of arrests.

One Globe report called Mulligan “an old-fashioned, bare-knuckles sort of cop — headstrong and street-savvy and blunt.”

“Most people take the family first and their job second,” Michael Carroll, then-vice president of the detectives union, told the Globe the day of Mulligan’s murder. “John really enjoyed the job, to the extreme. He was relentless.”

But his reputation in the department faltered in the years before his death.

In 1989, Mulligan was suspended after an internal investigation found he “double-billed” the force for some of his overtime shifts, according to the Globe.

In 1992, he was branded as a “problem officer” by the department, whose internal audit found he ranked fifth out of its 1,950 officers for having the most complaints filed against him. Mulligan was the subject of 24 misconduct investigations in his 27-year career.

Boston Police Det. John Mulligan, as seen in 1978.

And in 1986, Mulligan was mentioned in a federal corruption probe of the force, in which a drug dealer testified the detective was “among many officers who protected his operations in exchange for payoffs,” the Globe wrote following Mulligan’s death.

Mulligan invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination when he went before a grand jury; he was not charged with a crime.

In 2015, when Suffolk Superior Court Judge Carol Ball ordered a new trial for Ellis, she wrote how Ellis’s defense attorney, Rosemary Scapicchio, discovered new evidence that “suggests there was corruption within the investigation of Mulligan’s homicide itself.”

Ball’s ruling indicated police received tips that Mulligan was involved in crimes with the detectives who investigated his death, including the armed robbery of a suspected drug dealer only 17 days before his death, according to the Globe.

Ball also wrote that authorities received tips from three different people that implicated a city police officer and his son in Mulligan’s murder, the newspaper reported. The tips said the pair believed the detective had harassed a teenage female relative — all information Ellis’s defense did not receive, Ball said.

Richard Mulligan, the detective’s brother, said his brother was never charged with a crime.

“Sean Ellis is guilty,” he said. “The evidence is compelling. I don’t think he’s fully paid for what he did.”

Prosecutors at the time also fired back, saying that Ball’s findings did not present “one single piece of evidence” that “contradicts the strong evidence that proved Ellis’ guilt at trial.”

“In our judgment, this was a conviction based on direct, reliable, corroborated evidence,” Jake Wark, a spokesman for then-Suffolk County District Attorney Daniel Conley, told the Globe. “We fully intend to present that evidence to a new jury if necessary.”

Still, in 2016, the state Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of a new trial for Ellis based on the new evidence of corruption inherent in the case, including that the FBI had heard there was a contract out for Mulligan’s murder and that he and other detectives robbed a marijuana dealer of over $26,000 weeks before his death, according to the Globe.

Ellis’s cousins were murdered days after the slaying.

Ellis’s cousins, Celine Kirk, 17, and Tracy Brown, 23, two sisters, were shot and killed on Sept. 29, 1993 — three days after Mulligan’s death — in a Mattapan apartment.

Craig Hood, 18, of Brockton, confessed to the killings — carried out in front of Brown’s two young children — and told police the incident stemmed from an argument he had with Kirk over a gold chain, according to the Globe.

Hood was convicted in 1995 of second-degree murder and sentenced to two consecutive life terms with eligibility for parole starting in 2033.

Following the murders, relatives of Kirk and Brown said Kirk was at the Walgreens the night Mulligan was murdered with Ellis, buying diapers for their niece, according to the Globe. The family members, who asked not to be identified, also had said Hood and Patterson knew one another, the newspaper reported.

One relative told the Globe that Ellis was questioned by police about his and Kirk’s presence at the Walgreens the night of the murder only after the two sisters were killed.

Investigators, at the time, said only three employees were in the store at the time of Mulligan’s murder.

Ellis was arrested hours after the burials of Kirk and Brown.

Two of the three detectives at the helm of the investigation later pleaded guilty to federal corruption charges. The third was granted immunity in exchange for his testimony.

Walter Robinson, left, and Kenneth Acerra, right.

Boston Police Dets. Walter Robinson, Kenneth Acerra, and John Brazil played pivotal roles in the investigation against Ellis.

The trio helped secure witnesses and physical evidence from Mulligan’s murder, Ball, the Suffolk Superior Court judge, wrote in 2015. All three had also been the detectives later accused of joining Mulligan in robbing the suspected drug dealer just a little more than two weeks before his death.

Ball wrote that the prosecution was in a “rush to judgement” with Ellis’s arrest and subsequent conviction.

“From the beginning of the investigation, the apparent criminal misconduct of Detectives Acerra, Robinson, Brazil, and Mulligan gave the surviving partners a motive to cover up any evidence of their own crimes and to contribute to a quick arrest and conclusion to the investigation so that it did not turn in their direction,’’ Ball wrote, according to the Globe. “Defense counsel should have had the opportunity to make that argument to the jury.’’

In 1998, Robinson and Acerra pleaded guilty to federal charges stemming from a 27-count indictment, including that they stole over $200,000 and took bribes in exchange for offering lenient sentence recommendations, according to the Associated Press.

Brazil was granted immunity from prosecution in exchange for his testimony.

In 2016, the state Supreme Judicial Court ordered another trial for Ellis based on the new evidence that Mulligan was a corrupt officer and on his association with the trio of detectives who investigated his death.

“These detectives would likely fear that a prolonged and comprehensive investigation of the victim’s murder would uncover leads that might reveal their own corruption,” the late Chief Justice Ralph Gants wrote in the court’s decision.

Additionally, Sanchez — the key eye witness who identified both Ellis and Patterson as the two men she saw around Mulligan’s car — and Acerra knew one another, GBH reported.

Acerra and Sanchez’s aunt had been romantically involved at one point. Sanchez, and her husband, had initially identified another man — not Ellis — as the one she saw at the scene, according to the Globe.

Charges against Ellis were eventually dropped — but prosecutors maintained Ellis and Patterson are guilty.

Sean Ellis embraces his sister, Lasalle Ellis, in the courtroom at Suffolk County Superior Court on Dec. 18, 2018, one day after Suffolk County District Attorney John Pappas said he would not retry Ellis for the 1993 murder.

Prosecutors have long said that even with the compelling corruption evidence introduced in recent years, there remain elements of the case that support the case against Ellis.

The information surrounding Mulligan’s own past does not delineate from the facts that Ellis possessed the murder weapon and his then-girlfriend’s fingerprint was found on Mulligan’s pistol.

Although prosecutors intended to bring Ellis back to court after his release in 2015, charges against him were withdrawn in December 2018.

“The trial evidence and testimony in 1995 proved Mr. Ellis’ guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Jurors at the time called the case against him overwhelming,” then-acting Suffolk County District Attorney John Pappas said. “But the passage of more than two and a half decades has seriously compromised our ability to prove it again. For this reason, my office will file paperwork today ending the prosecution of Mr. Ellis for first-degree murder and armed robbery.”

Pappas noted however that Ellis’s two convictions for possessing the murder weapon and Mulligan’s pistol remained “undisturbed.”

He also acknowledged that the decision to drop the more serious charges had to do with “three corrupt police detectives.” Pappas said prosecutors did not believe Mulligan was involved in the corruption, but “it is now inextricably intertwined with the investigation and critical witnesses in the case.”

Furthermore, the decision to withdraw charges was not made based on the notion that Ellis was wrongfully convicted, according to Pappas.

“Let me be clear: that is not the case here,” he said. “If at any point we had any reason to believe that Mr. Ellis was wrongfully charged or convicted, we would have acted on it immediately.”

Patterson, whose murder conviction was overturned on an appeal, eventually received a reduced charge of manslaughter in 2006, according to the Globe. He was ordered to serve 22 years but was soon released based on good behavior and time already served.

“In the 25 years since Det. Mulligan was murdered in cold blood, not one piece of evidence developed by prosecutors, defense counsel, or anyone else has pointed to anyone but Sean Ellis and Terry Patterson,” Pappas said. “Of all the people in all the world who might have killed John Mulligan, only they were present at the time and place he was killed — by their own admissions, supported by eyewitnesses and physical evidence.”

Watch the trailer for “Trial 4”:

Get Boston.com's browser alerts:

Enable breaking news notifications straight to your internet browser.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com