Louisiana prisoner 358331 has lived the past 28 years as a shadow.

Held in conditions of solitary confinement for 27 years, the inmate has cycled between disciplinary units in different prisons, including a six-year stint on the old death row at the notorious Angola prison.

Separated from the general penitentiary population, the prisoner has, according to legal letters, endured a singularly harsh existence in custody: spates of extended lockdowns, no access to in-person classes, death threats and sexual humiliation.

And prisoner 358331 is unique. She is the only woman on death row in Louisiana.

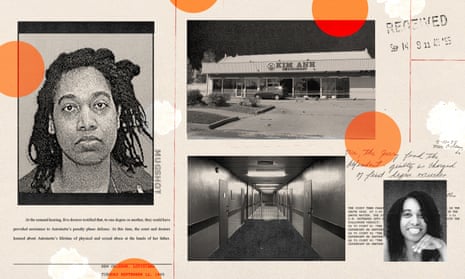

In 1995, Antoinette Frank, a serving New Orleans police officer, was convicted of a crime that still resonates in parts of the city today. She was found guilty of a triple murder, along with a male accomplice, for gunning down a fellow officer and two young restaurant workers during an armed robbery. It was a case that gripped Louisiana, part of an extensive list of violence and corruption scandals tied to local law enforcement at the time. And it has long spawned sensationalist true crime retellings.

Next month, the public is set to hear from Frank herself – for the first time since her conviction. As part of an extraordinary effort to secure clemency for all but one of Louisiana’s 57 death row inmates, Frank’s case will be among the first to come before the state parole board in a series of hearings.

The board will hear new evidence detailing what experts have described as “psychologically catastrophic” trauma resulting from extensive physical abuse and repeated rape that Frank, now 52, endured throughout her childhood and youth.

It is likely to form the basis of a bid for mercy – in her words, for the board to “see humanity in me and determine that my life has value”.

But her application is expected to be met with stiff victim opposition. And along with all the others filed in this mass clemency bid, her request comes at a political inflection point in Louisiana, with a gubernatorial election just a few months away in which a hard-right, pro-death penalty Republican holds a strong lead in the polls and has already sought to block the clemency process moving forward.

The Guardian has examined dozens of previously unreported documents related to Frank’s bid for clemency, including medical records, psychological reports, affidavits and legal filings for the reporting of this story. They present an alternative personal narrative to the common, often lurid, depiction of one of the perpetrators of an infamous triple murder, and the state’s sole female death row inmate.

“It would be deeply disheartening if the [parole] board fails to recognize that Antoinette, a person who survived years of torture and rape, deserves mercy,” said Sandra Babcock, a law professor at Cornell University and one of the country’s foremost experts studying women on death row. “Her case exemplifies the reasons for the clemency process, allowing a decision-maker to look at the person’s entire life and make a reasoned and compassionate decision about the appropriate punishment.

“It’s hard to imagine someone more worthy of that compassion than Antoinette.”

Dr Sarah Deland first interviewed Antoinette Frank in May 2001. Frank was not who the assistant professor of psychiatry at Tulane University had expected to encounter.

“The case was so highly publicized, and she had really been castigated,” Deland recalled in an interview. “But she was very meek. Very eager to please. She did not strike me at all as someone interested in escaping any responsibility for what she’d done.”

But Frank was guarded, too. And after their first prison interview, Deland had only learned about a fraction of the childhood abuse Frank suffered.

The psychiatrist had been hired by new defense lawyers as the case wound through the appeals process. Frank’s 1995 trial came less than six months after she was charged, amid a media frenzy. She had no mitigation specialist assisting at her trial – a professional commonly tasked with assisting those who face the death penalty to advocate for their lives, often by finding evidence of past trauma.

It meant that her experience of extended and extreme abuse was never heard by the jury who sentenced her to death. Their deliberations concluded after less than 45 minutes.

The sentence was eventually upheld by the Louisiana supreme court in 2007 in a split 5-2 ruling, but a dissent from Louisiana’s chief justice, Pascal Calogero, described the sentencing process in Frank’s trial as “fatally flawed”, citing her lack of expert assistance.

Nonetheless, Deland continued working with Frank’s defense after the ruling. She interviewed her twice in 2009 and finally produced an extensive and disturbing report documenting full details of the physical, sexual and psychological abuse Frank had endured at the hands of her father, Adam Frank Sr, as she grew up in poverty in the rural town of Opelousas and in New Orleans.

Deland interviewed Frank for over seven hours in total – and eventually absorbed her full story, much of it corroborated with documents and secondary accounts.

The beatings began at an early age.

Adam Frank, a Vietnam veteran, had PTSD and may himself have been a victim of incestuous abuse, according to the report. Descriptions of the physical and psychological assaults against his young daughter are contained in a set of clinical notes from Veterans Affairs doctors who treated Adam Frank in the early 1970s. Extracts were reviewed by the Guardian.

An entry dated the third of October 1973 states: “Patient got angry w/ children this past week and struck 2 y/o daughter [Antoinette] several times.”

Fourteen days later, another entry states: “Patient becoming more abusive toward daughter – started to choke her this past week. It appears this is becoming a rather dangerous situation.”

The clinician prescribed antipsychotics and recommended removing the children from the family home, which did not occur.

According to Deland’s report, Adam Frank would lay booby traps around the house, was prone to violent rage and regularly beat his wife in front of his children, often breaking her bones. On a number of occasions he disconnected gas lines from their appliances and filled the home with gas. On others, he drove his wife and children to a railway line and threatened to kill them all in a collision.

The report contains a detailed, graphic account of protracted incestuous rape, which began as Antoinette Frank entered puberty and continued into her early adulthood.

Of the first time her father raped her, the report states: “She screamed out in pain; he stopped and comforted her, but then he attempted to penetrate her again and this time he put his hand over her mouth to stifle her screams.”

Frank had three abortions as a result of her father’s numerous rapes, according to the report. The first was when she was 16 years old – “her father told her she had to do it if she loved him,” the report states.

At around this time, Frank’s mother left the home along with her three siblings. But Antoinette was forced to remain with her father and the sexual abuse continued.

“Basically, Antoinette was payment for the rest of the family being able to leave,” Deland said in an interview – the first she has given about the case.

The final abortion occurred when she was 20, according to the report, just three years before the triple murder. The two doctors that lawyers say conducted the procedures have since died. But a recent hospital admission document, seen by the Guardian, notes three terminations on Frank’s record stating: “pregnancies result of sexual abuse”.

She made three attempts at suicide, starting as a teenager.

Frank joined the city police department at the age of 22. Despite failing two psychiatric evaluations, she was allowed to join the force after her second application as the department experienced a hiring shortage. According to a signed affidavit from one of Frank’s classmates at the police academy, Roderick Baudy, Frank’s father would drop her off and pick her up from class each day. The recruits noticed they behaved “as if they were lovers” and at social events she would sit on her father’s lap.

Reached by phone, Baudy said he stood by his affidavit, which was signed in 2009.

Frank reported her father missing in August 1993, a little more than a year before the killings. He has not been seen since.

Deland’s report concludes that Antoinette Frank had PTSD and probably dependent personality disorder resulting from her abuse. It left her “very susceptible to manipulation”. “Ms Frank’s beliefs, emotions, behaviors and judgment have all been negatively impacted in a complex and long lasting manner,” the report states.

The findings are supported by other experts, including the clinical psychologist Dr Leslie Lebowitz, who reviewed Frank’s file and concluded in June 2009 that Frank had “endured multiple kinds of the most toxic traumatic stress imaginable”, making it likely “that as an adult she will vacillate between a relatively shut down, numb, robotic or dissociative state, on the one hand, and feelings of terror, helplessness, and confusion on the other”.

Two jurors who originally sentenced her to death now say they would not have done so if they had been aware of this long history, according to signed affidavits, reviewed by the Guardian.

“This information about abuse would have made a difference in my sentencing decision,” wrote one of the former jurors. “Now that I know about her childhood I don’t think she should be executed.”

The murders occurred past midnight in New Orleans East on 4 March 1995, days after the city had celebrated Mardi Gras.

Frank had worked an occasional off-duty security detail at a Vietnamese restaurant called Kim Anh, run by a tightly knit family, the Vus. She shared shifts with a fellow police officer, Ronald “Ronnie” Williams II, a father of two young children.

Months earlier, Frank had struck up a friendship with an 18-year-old named Rogers LaCaze, a known local drug dealer, whom she met during a police interview after he had been shot. Frank has maintained she had tried to mentor him and that their relationship was not sexual.

Accounts of what unfolded on the night of the killings have varied over the years, but prosecutors at trial concluded that the pair had visited the restaurant multiple times that evening.

As the business closed, Frank used a stolen key to enter the premises and forced two of the Vu siblings, Chau and Quoc, as well as another employee to the back of the building.

LaCaze shot Williams to death, according to prosecutors.

As the shots rang out, the two siblings fled and hid inside a refrigerator. Two other siblings, Ha Vu and Cuong Vu, were then gunned down at close range as the assailants searched for hidden cash from the register.

Chau and Quoc heard the volley of gunshots that killed their siblings.

Frank fled but returned to the scene of the crime shortly after 911 was called, arriving in a police patrol car. The hidden survivors instantly identified her as one of the killers before she and LaCaze were arrested. Frank and LaCaze were convicted of first-degree murder.

LaCaze initially confessed to police but later recanted and claimed innocence. He was found guilty and sentenced to death before Frank’s trial. During the appeals process, due process issues at trial were identified, and his sentence was downgraded to life without parole.

That left Frank as the only participant facing death over the Kim Anh murders.

Her defense team called no witnesses during the guilt phase of the trial. During the sentencing phase, as prosecutors urged the jury to sentence her to death, they closed by stating: “Was that a woman that walked in there and massacred those people? No, ladies and gentlemen, that was a murderer.”

Frank’s clemency petition includes an admission of her involvement but continues to suggest she was not a willing participant in the robbery or the murders.

In a police interview after her arrest, Frank maintained that LaCaze had held a gun to her head as she opened fire. The account is repeated in her clemency application and supported by prosecution testimony. A witness, Kim Carter, testified during the appeal process and claimed that LaCaze, who was her friend, had confessed to this during a jailhouse phone call.

“I ache to the core of my being for the victims, their loved ones, and everyone who’ve been affected by the horrific tragedy that occurred at the Kim Anh Restaurant in March of 1995,” a 2021 letter from Frank included in the petition states.

The Kim Anh restaurant has since moved locations to a strip mall in a nearby suburb. The family moved after the old spot was destroyed when New Orleans’s federal levees failed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, flooding the city.

There are few reminders of the tragedy that occurred in 1995. But hanging behind the cash register is a local newspaper article about Kim Anh’s post-Katrina reopening in 2006.

“Double-dose of tragedy fails to stop Kim Anh owners,” the headline states.

Still, members of the Vu family remain haunted by the murders. When Quoc Vu, now a civil engineer, learned that Frank was being considered for clemency, he submitted a letter to the board expressing staunch opposition.

It explained that he still suffers from nightmares and anxiety attacks, despite the almost three decades that have passed. He has since obtained a permit to carry a gun for self-defense, which he carries everywhere possible.

“I will never forget the day it happened,” Vu’s letter, which he shared with the Guardian, states. “I am scarred for life by it … Since 1995 till now, my family has suffered with the memories of that day.

“I never feel safe anymore anywhere.”

Williams’s father, Ron Williams, declined to discuss Frank’s clemency petition when contacted recently. He has previously described the loss of his son as “by far the worst experience” of his life.

A regular attendee at hearings centering on the Kim Anh killings over the years, Williams once expressed his frustration at the case’s years-long appeals process by saying “it’s absurd” that criminals are not “made to answer for their crimes”.

The Orleans parish district attorney’s office did not respond to a request for comment on whether it will oppose or make any statement to the parole board at Frank’s clemency hearing.

The mass clemency applications have been mired in politics since they were announced in June.

Louisiana’s outgoing Democratic governor, John Bel Edwards, who assumed office in 2016, announced his opposition to capital punishment in March of this year. But as the state lurches towards a gubernatorial election this year, in which the Republican Jeff Landry leads comfortably, according to polling, the petitions could represent a last real chance at reprieve for some.

Although Louisiana has not carried out an execution since 2010, Landry, the state’s incumbent far-right attorney general, has long advocated for its continuance, including the use of the electric chair, firing squads and hangings.

“We’re entering into a really barbaric, dangerous era, where we will have lynchings in the United States, if Landry has his way,” said Samantha Kennedy, executive director of the Promise of Justice Initiative, a New Orleans-based legal advocacy group involved in the petitions. “We are in a critical period, which is really about the future and where we’re going to be. Are we going to kill people in this state, or are we going to recognize the frailties of humankind and turn towards mercy?”

Landry has attempted to block all 56 clemency petitions from being heard, and last week he filed a lawsuit challenging the applicants’ eligibility. But the moves have faced broad criticism and have no legal basis, according to Edwards and the many defense attorneys involved in coordinating the petitions.

Capital punishment in Louisiana, just as in other states, holds a history of stark racial and mental disparities – 42 of the 57 people currently on death row in the state are people of color, and 67% are Black. At least 23 cite evidence of intellectual disability.

Nine people sentenced to death in Louisiana in the past 24 years have since been exonerated.

Still, the clemency filings have moved the needle into uncharted territory here. There is precedent for mass commutations in other states, following a move 20 years ago in Illinois when the then governor, George Ryan, commuted the sentences of all 167 death row inmates. But there is nothing of comparison in the US south, where the sentence is imposed more readily than elsewhere.

Louisiana has seen just two people granted clemency from the death penalty since 1976. Its parole board has not heard a capital case in a decade, according to advocates, plunging the scheduled hearings into a level of significant uncertainty.

A majority decision is required from the board’s five members to grant clemency and commute a sentence to life without parole. They will weigh factors including the circumstances of the offense itself, the individual’s prison record, and “community attitude”, which includes victim opposition, before making a subjective ruling. And only with the board’s approval will a petition reach the governor’s desk.

“It can be quite unpredictable,” said Dr Marcus Kondkar, an associate professor of sociology at Loyola University New Orleans, who has long observed the board’s handling of life-without-parole clemency hearings. “It’s not a legal procedure where there is grounds for appeal, and so it’s very much about personalities. In my view, the types of narratives that tend to be successful before the board tend to lack any kind of nuance or qualifying complexity of any kind.”

Many Louisianans have a viscerally negative reaction to Frank’s case in particular.

At the time, the Kim Anh murders became synonymous with the culture of corruption and brutality that New Orleans’s police department was known for.

A year earlier, another New Orleans police officer had orchestrated the deadly shooting of a woman who filed an excessive force complaint against him. Then, in Katrina’s chaotic aftermath, New Orleans police unjustifiably killed four men in three separate cases.

The city and federal governments finally signed a sweeping, 492-point reform plan for the police department in 2012. That pact has since lifted the police department out of some of its history’s lowest and darkest depths, but the agency had not yet managed to fully implement it more than a decade later, starkly illustrating the scale of the work that needed to be done.

Antoinette Frank’s hearing is scheduled for the first batch of five cases to be heard on 13 October. Its announcement drew derision from some rightwing observers in New Orleans’s criminal legal system, as modern day – often sexualized – retellings of the murders continue to proliferate in media. Such disparagement, said Dr Babcock, has for decades been a fixture of how women on death row are viewed in public discourse.

“Women who are sentenced to death are typically described in broad stereotypes,” said Babcock. “They are demonized in ways that have everything to do with their gender, both in the conclusions that people draw about women who behave in ways that are not typical of feminine archetypes – but in a case like this it goes deeper, in that women, particularly Black women, who are victims of violence are not believed.”

Babcock’s co-authored recent research concludes that 96% of the women on death row in the US have experienced gender-based violence, with almost 90% having experienced at least one episode of sexual or physical violence. There are currently 47 cisgender women on death row.

Still, said Babcock, the violence experienced by Antoinette Frank is among the most extreme she has encountered. A letter sent to Governor Edwards this week, signed by over two dozen experts or organizations studying gender-based violence, urges the outgoing Democrat to commute her sentence to life.

“It is essential to understand how a survivor’s experiences of gender-based violence can explain her participation in a violent crime,” the letter states.

Frank views the opportunity to speak before the board as a “privilege, not an entitlement”, said her attorney Letty Di Giulio.

“I think if she had spoken 28 years ago, she would sound very different to how she does now,” said Di Giulio, pointing to Frank’s deep Christianity and a description of her client as a “gentle and timid person”.

“She has spent that time doing incredible self-help work. She told me recently: ‘I sort of had to teach myself to have a voice, because I wasn’t allowed to have one. I didn’t really know what it sounded like.’”

In just a few weeks, the parole board will hear it for the first time. It could be the difference between life and death.