My sister Karina has died at the age of 48. She tested positive for coronavirus early last week and it quickly attacked her stomach, her lungs and her kidneys. When she was admitted to hospital the carbon dioxide levels in her blood soon began to rise, a worrying sign.

On Saturday we all variously FaceTimed her to tell her how much she meant to us and tried to raise one more of her life-affirming laughs, desperately scanning the screen for any sign of responsiveness, any sign of hope. By then, however, we knew that she was only being kept alive in hospital by her BiPap (bilevel positive airway) machine and on Sunday lunchtime we were, with great kindness and tact, told we should say our final virtual goodbyes.

A nurse, Patricia, held up Karina’s iPad while my mum, via FaceTime on her mobile, narrated a favourite story of hers for the last time and thanked her for the happiness she had brought us all. Mum then held up her home phone to her mobile, where my other sister, Kirsty, at hers, was able to say how much she loved her and would miss her. And then Kirsty held up her husband’s phone to hers where I, on loudspeaker, from my house, played Karina one of her favourite songs and told her how proud I was to have been her brother and what gratitude I felt for what she had taught me about life.

We had wanted to be with her together as a family and, under lockdown conditions – and knowing my mother’s strengths lie in areas other than navigating Zoom meetings – it was as good as we could have hoped.

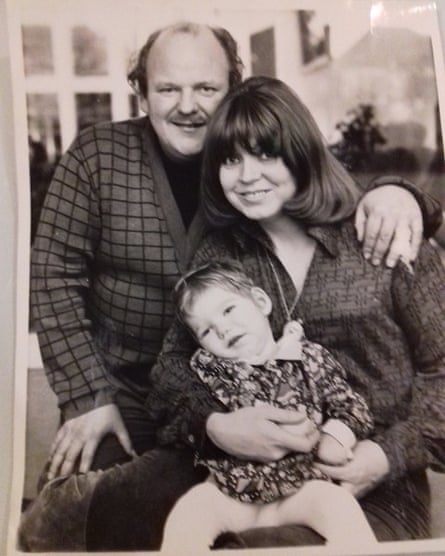

Karina’s death is what we have feared ever since the disease took hold so rapaciously in Italy in February. Her lung capacity was so diminished that we knew, given the reports of its effects, that it was likely to prove incredibly dangerous for her. Her conditions weren’t just “underlying”, they were life-defining, for her and for us, even if she remained unaware of their severity. But Karina had defied predictions her entire life.

She had suffered a lack of oxygen at birth that caused severe brain damage, had been left paralysed from the waist down after a life-saving operation on her spine aged 19, had been intubated and suffered kidney damage six years ago with sepsis – the last time we said our putative goodbyes to her – and was in hospital with chest infections regularly throughout her life. And yet every time, when you thought she couldn’t possibly take any more, she defied us.

Along with my mother’s ferocious determination to keep her alive, she defied medicine, she defied doctors, she defied prognoses, she defied the capacity of human endurance. And she would look at you and smile, as if to say: “Yep. I did it again.” She was heroic and continually inspiring. In fact she had a daredevil’s spirit, forever finding joy in activities many might have shied away from.

When we were younger she used to love fairground waltzers, despite the rest of us sating our search for thrills by hooking ducks. Waltz though we did, and our terrified screams would compete to drown out her increasingly riotous chuckles. She was also mischievous and, even without language, could let you know how much she appreciated the ridiculous. Early in the 1990s she started laughing every time the EastEnders theme tune came on, and we could never understand why.

So it was coronavirus that killed her. It wasn’t her “underlying conditions”. Prior to her diagnosis, she hadn’t been in hospital for 18 months – an unusually care-free period for Karina. No, it was a virulent, aggressive and still only partially understood virus that was responsible, a virus that is causing thousands of people, despite the unstinting bravery of the medical staff of this country, to say a distanced goodbye to relatives who would still be alive had they not contracted it.

No one could describe Karina as weak: she did not have it coming, she was no more disposable than anyone else. Her death was not inevitable, does not ease our burden, is not a blessing. She was vulnerable, yes. She needed the care of others to live. I will remain for ever grateful to the hundreds of caregivers who have, at one point or another, looked after her with such kindness and dedication, some of whom have maintained a relationship with her long after their retirement. Grateful too to live in a country that makes provisions of care free to all, no matter one’s need, however stretched and fraying their chronic underfunding increasingly makes them.

But this disease is not just killing people who would have died soon anyway. It is making the lives of those most in need of our care and compassion even harder, even more fearful. And if there is anything that I hope might come from Karina’s death, from the tens of thousands of other deaths caused by this disease and its insidious spread, it is that as a country, from government both national and local, we might make our focus the easing of those lives in the future.

My mother, like any parent of a child with disabilities, has spent Karina’s life fighting for more support, more options, more recognition. Twenty-five years ago, frustrated at the paucity of provision, she established her own charity to build a home for six young adults with severe disabilities. Roy Kinnear House, named after my father, opened in 2000. It was 10 minutes’ drive from my mum, where Karina continued to live with others in happiness and in the best of care.

But it has been exhausting, even to watch. The last two months have revealed to all of us the truth of Yeats’s line that “All things hang like a drop of dew upon a blade of grass”. For many people though, as it was for my sister’s life, that sense of fragility and peril is a constant.

Maybe we might transfer our common sense of purpose, our shared determination to “defeat” an “enemy” that “preys” on the needy, once “the fight against coronavirus” has been “won”, to invest – financially and emotionally and with a similar level of heroism and selflessness – in the lives of those who will continue to need it most. It is a sustaining hope for now, at least.

Karina was ebullient, brave and wry, with a passion for noise, laughter, family and chaos. And those that engaged with her, knew her, loved her, were rewarded beyond their imagination by her friendship and trust. They grew to learn, inexorably and unalterably, that our spirits exist far more tangibly than our abilities. What a lesson. What an inspiration.

Rory Kinnear is an actor and playwright