The Big Picture

- Roger Ebert continued to review movies until the end of his life, despite the challenges of his cancer, which inspired others facing the same disease.

- Terrence Malick's To the Wonder was Ebert's last review and showcased the director's iconic style and departure from his previous period pieces.

- Ebert defended Malick's filmmaking choices and believed that not every film needed to explain everything, highlighting the film's ambitious portrayal of spiritual longing.

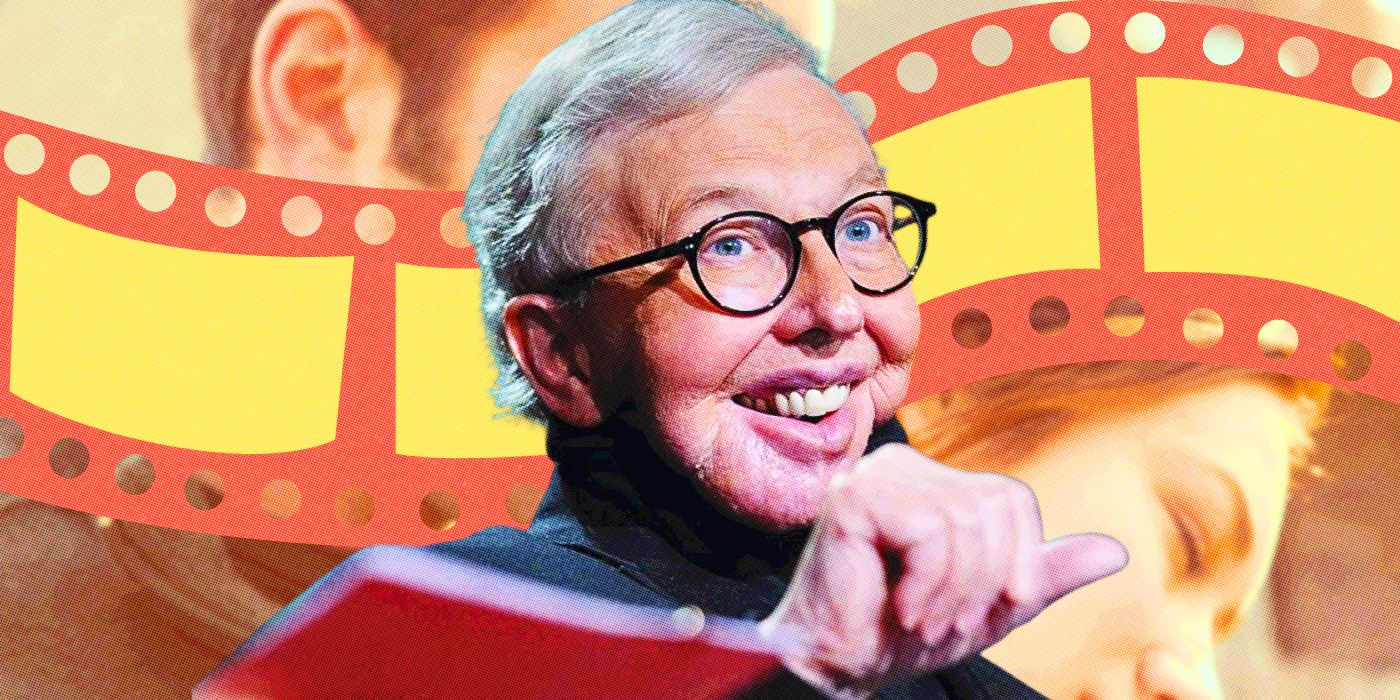

Roger Ebert, who was for several decades the face of film criticism, died on April 4, 2013. For several years he had been managing life with a particularly destabilizing cancer, which had altered his appearance, and taken away his ability to eat, drink, and speak. Many public figures would have withdrawn, but Ebert remained visible while making the significant accommodations his health forced him to make. Because he continued reviewing movies until the end of his life, there has always been a lot of curiosity about what his last review was, and whether there might be any special meaning to what he said about it. His last review was for Terrence Malick's To the Wonder. This is clearly a movie with a significant place in film history. But what it means is that it's also the subject of Ebert's final review is more subjective.

Roger Ebert Was One of America's Hardest-Working Film Critics

Roger Ebert's decision to keep working, to demonstrate that life went on even with cancer, has always meant a great deal to the many others who also live with the same disease. That decision was very much in character for Roger Ebert. His career had a certain compulsive presence. He reviewed anything and everything that showed up on an American movie screen. Not only on his TV show with Gene Siskel, but in print, where he gave every movie the same 500 thoughtful words. While his decision to keep working through cancer has sometimes been attributed to a heroic lack of vanity, he himself identified this work ethic as a form of pride. He even candidly speculated that his need to get back to his show, during an earlier bout with his cancer, had caused him to make a reckless choice in his treatment. But being a workaholic was largely something he'd come to terms with about himself. When his health finally forced him to take a step back even from writing, he jokingly called it "A Leave of Presence," because, even working at a slower pace, he'd still be putting out a lot of material. In that announcement, (at the end of a long list of all the ways he'd be keeping busy), he wrote, "I'll be able at last to do what I've always fantasized about doing: reviewing only the movies I want to review." He died the day after it was published.

If it was Ebert's mission to review absolutely every movie, that almost led to an outcome he'd probably have found darkly funny. The day of Ebert's death, the Los Angeles Times published that his last review had been for The Host, an adaptation of a minor work from the author of the Twilight series of YA novels: "it makes you wish the final words of the beloved critic could have been spent on a film that was far better -- or far worse."

This wish, of course, came true. As Jim Emerson, Ebert's long-time web editor, and a wonderful critic himself, was quick to clarify, Ebert had filed some reviews that had not yet been published. The last of these was not the review for The Host (a close call though!) it was for Malick's To the Wonder. People were relieved that Roger Ebert's last review turned out to be a "thumbs up." But To the Wonder is more than that, it's a pivotal movie from one of America's most important filmmakers. And so, though there were other Ebert reviews that were technically published even later because of those films' release dates, each of them comes with a disclaimer to clarify that it wasn't the last one he filed, making sure that the honor would remain with Malick.

'To the Wonder' Is a Challenging Film by an American Master

Terrence Malick was roughly Roger Ebert's age, and Ebert had been reviewing his films with reverence since his first, Badlands, was released in 1973. Malick spent his filmmaking career defining one of the most iconically recognizable styles in cinema, one which he has never deviated from.

The Terrence Malick aesthetic is easy to spot. The story is presented primarily in montage. There's very little onscreen dialogue; the work of advancing the plot is instead left to voiceover, delivered in poetic generalities. The images themselves are decadently gorgeous. Malick famously does a lot of his filming at "magic hour," the time of day just before sunset or after sunrise, giving his exteriors an otherworldly glow. Though the connection between the voiceover and the imagery is usually pretty clear, a lot of connective work is left to the viewer. It's not the most accessible style. But, perhaps thanks in part to critics championing his work, Malick was given leeway to make movies the way he liked.

To the Wonder contains all of Malick's hallmarks. But it was in many ways a departure. For one thing, his previous films had all been period pieces with epic subjects. The New World told the story of Pocahontas. The Thin Red Line depicted the fighting in the Pacific during World War II. Days of Heaven was about a murder at the dawn of the 20th Century. His most recent movie, The Tree of Life, which won the Palme d'Or at Cannes, told the smaller-scale story of a family during the 1950s. But it was the director's own life story, and it included an interlude set at the dawn of life on earth. To the Wonder was fully contemporary, and told the story of ordinary people.

What Is 'To the Wonder' About?

Ben Affleck plays Neil, who lives in an upscale but nondescript housing division in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. On vacation in Paris, Neil meets Marina (Olga Kurylenko), they begin an affair, and he invites her and her ten-year-old daughter to live with him in America. She gives into their relationship with abandon, while he often seems to be going through the motions, playing the part of a swooning lover as best as he can, for her benefit. In America, they grow frustrated with each other (their story is mostly narrated from her perspective), and she returns to France when her visa expires. Neil begins seeing Jane (Rachel McAdams), but has many of the same problems giving of himself. Marina returns, and they give it another shot. Neil is at the center of the story but is closed off from the people in his life, and the camera only catches glimpses of his face. In an adjacent storyline, Javier Bardem plays the town priest, who seeks the closeness to God he knew in his youth. Everyone is seeking passion but is caged by self-awareness. The Oklahoma landscape is beautiful but polluted with strip malls, housing tracts, and chemical plants.

It wasn't only the film's subject matter that seemed ordinary. Terrence Malick's other films were painstaking recreations of the past; they often took years to create and recover from. Malick releases were rare events; there had been a twenty-year gap between Days of Heaven and The Thin Red Line. But To the Wonder showed up less than two years after The Tree of Life. Perhaps that was why the movie was resisted as few Malick films had been before. His stylistic idiosyncrasies were given respect when he seemed to have returned from a journey by time machine, but not as much when he seemed to have just gotten back from down at the gas station. Malick was thought to be repeating himself, to diminishing effect.

Roger Ebert Stood Up for Terrence Malick's Filmmaking Choices

Roger Ebert understood the challenges To The Wonder presented. "A more conventional film would have assigned a plot to these characters and made their motivations more clear," he wrote. "There will be many... dissatisfied by a film that would rather evoke than supply." And while he understood that reaction, he felt the film's ambitious portrayal of spiritual longing more than justified its lack of a structured narrative. "Why must a film explain everything? Why must every motivation be spelled out? Aren't many films fundamentally the same film, with only the specifics changed? Aren't many of them telling the same story?"

In a recent interview in Vanity Fair, Martin Scorsese related a quote from fellow legendary director Akira Kurosawa: "I’m only now beginning to see the possibility of what cinema could be, and it’s too late." Kurosawa had said this when receiving a lifetime achievement Oscar, at 83. Scorsese, now 80, proclaimed "now I know what he means.” The creative process has no sense of how late it is. When legends pass, it's never with perfect timing. They leave with some of their ideas still unexpressed.

In the ten years since To the Wonder, Terrence Malick has completed three more feature films. Four films in a decade is a remarkable acceleration, in the context of Malick's career. Is he rushing them out because he senses that soon it will be "too late"? And was Ebert able to keep up with him on that path because he too, had the perspective of a man who was running out of time?

It's an interesting theory, but reading Ebert's 1978 review of Malick's Days of Heaven seems to disprove it. 35 years in the past, Ebert responded to Malick in a nearly identical way. Acknowledging that the film "doesn't really tell a story," but is instead an "evocation," he sets it apart from the typical film that is "jammed with people talking to each other all the time."

Kurosawa said "I’m only now beginning to see the possibility of what cinema could be," as if he was about to reinvent himself, and the medium of film. But what would he have really done with 83 more years? Make another 83 years' worth of Kurosawa films. Same with Scorsese, or Malick, given all the time in the world. And Ebert, if he'd lived another lifetime to review those movies, would have continued to express himself as he always had.

Not that every artist is only repeating themself; every individual thing that we make has its own details that set it apart. And of course, the volume means something on its own. For Ebert, reviewing every movie meant that every cinematic experience was meaningful and that this meaning could be set down in seven or eight paragraphs of plainspoken English. "From the Wonder," if you will. A style that could accommodate anything. And so, Ebert and Malick had one final collision. Ebert gave the movie three and a half stars, which seems fair. Terrence Malick is currently reported to be working on an extended cut of the film.