Slavery in the United States

Slavery in the United States was the legal institution of human slavery in the United States. Slaves were mostly Africans and African Americans. Slavery existed in the United States of America in the 18th and 19th centuries. Slavery existed in British America from early colonial days. Slavery was legal in all Thirteen Colonies at the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It lasted in about half the states until 1865. This was when it was banned in the entire country by the Thirteenth Amendment.

By the time of the American Revolution (1775–1783), slaves had been institutionalized as a racial caste. The caste associated with African ancestry.[1] When the United States Constitution was ratified in 1789, a small number of free people of color were able to vote. This was because they were men who owned property.[2] During and shortly after the Revolutionary War, abolitionist laws were passed in most Northern states, and there was a movement created to end slavery. Slave states tried to extend slavery into new Western territories. They wanted to do this to keep their share of political power in the country. Southern leaders also wanted to annex Cuba as a slave territory. The United States became split over the issue of slavery. It was split into slave and free states. The Mason–Dixon line divided the country. The line divided (free) Pennsylvania from (slave) Maryland.

While Jefferson was president, Congress prohibited the importation of slaves, effective 1808. Although smuggling (illegal importing) through Spanish Florida was common.[3][4] Slave trading within the United States, however, continued at a fast pace. This was because there was a need for labor due to the creation of cotton plantations in the Deep South. New communities of African-American culture were created in the Deep South. There were 4 million slaves in the Deep South before they were set free.[5][6]

Colonial America[change | change source]

The first Africans came to the New World with Christopher Columbus in 1492. An African crew member named Juan Las Canaries was on Columbus's ship. Shortly after, the first enslavement happened in what would later be the United States. In 1508, Ponce de Leon created the first settlement near present-day San Juan. He started enslaving the indigenous Tainos. In 1513, to supplement the decreasing number of Tainos people, the first African slaves were imported to Puerto Rico.[7]

The first African slaves in the continental United States came via Santo Domingo to the San Miguel de Gualdape colony (most likely in the Winyah Bay area of present-day South Carolina). It was created by Spanish explorer Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón in 1526.[8]

The colony was almost immediately disrupted by a fight over leadership. During the fight, the slaves revolted, and they ran away from the colony to hide among local Native Americans. De Ayllón and many of the colonists died shortly after from a sickness. The colony was abandoned. The settlers and the slaves who didn't run away went back to Haiti, from where they came.[8]

On August 28, 1565, St. Augustine, Florida was created by the Spanish conquistador Don Pedro Menendez de Aviles. He brought three African slaves with him. During the 16th and 17th centuries, St. Augustine was the where a lot of the slave trade in Spanish colonial Florida happened. It was the first permanent settlement in the continental United States to have African slaves.[9]

60 years later, in the early years of the Chesapeake Bay settlements, colonial officials found it difficult to convince people to come and work for them. This was because the weather and environment of the settlements was very harsh. There was a very high chance that people would die.[10] Most people came from Great Britain as indentured laborers. They signed contracts that said they would pay with work for their transportation, their upkeep, and their training, usually on a farm. The colonies had agricultural economies. These people were often young people who wanted to become permanent residents. In some cases, convicted criminals were sent to the colonies as indentured laborers, rather than being sent to prison. These people were not slaves, but they were required to work for four to seven years in Virginia to pay for the cost of their transportation and maintenance.[11] Many Germans, Scots-Irish, and Irish came to the colonies in the 18th century, settling in the backcountry of Pennsylvania and further south.[10]

The first 19 or so Africans to reach the English colonies arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619. They were brought by English privateers who had seized them from a captured Portuguese slave ship.[12][13][14] Slaves were usually baptized in Africa before sending them. As English custom then considered baptized Christians exempt from slavery, colonists treated these Africans as indentured servants. The African indentured servants joined about 1,000 English indentured servants already in the colony. The Africans were freed after a period of time. They were also given the use of land and supplies by their former masters.

| Date | Slaves |

|---|---|

| 1620–1650 | 824 |

| 1651–1675 | 0 |

| 1676–1700 | 3,327 |

| 1701–1725 | 3,277 |

| 1726–1750 | 34,004 |

| 1751–1775 | 84,580 |

| 1776–1800 | 67,443 |

| 1801–1825 | 109,545 |

| 1826–1850 | 1,850 |

| 1851–1866 | 476 |

| Total | 305,326 |

There were no laws about slavery in Virginia's early history. However, in 1640, a Virginia court sentenced John Punch, an African, to slavery. This was because he tried to run away from his service.[16] He ran away with two white people. The two white people were sentenced only to one more year of their indenture, and three years' service to the colony.[17] This is the first legal sanctioning of slavery in the English colonies. It was one of the first legal distinctions made between Europeans and Africans.[16][18]

In 1641, Massachusetts became the first colony to allow slavery through law.[19] Massachusetts passed the Body of Liberties. It banned slavery in many cases, but it allowed slaves to be held if they were prisoners of war, if they sold themselves into slavery or were bought somewhere else, or if they were sentenced to slavery as punishment by the government.[19] The Body of Liberties used the word "strangers" to refer to people bought and sold as slaves; they were generally not English subjects. Colonists believed this term referred to Native Americans and Africans.[20]

During most of the British colonial period, slavery existed in all the colonies. Slaves in the North usually worked as house servants, artisans, laborers, and craftsmen. Most were in cities. Many men worked on the docks and in shipping. In 1703, more than 42 percent of New York City households had slaves. New York City had the second-highest proportion of slaves of any city in the colonies after Charleston, South Carolina.[21] Slaves were also used as agricultural workers in farming communities. This included areas of upstate New York and Long Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey. By 1770 there were 397,924 Blacks in a population of 2.17 million. They were not spread out evenly. There were 14,867 in New England where they were 2.7% of the population; 34,679 in the mid-Atlantic colonies where they were 6% of the population (19,000 were in New York or 11%); and 347,378 in the five southern colonies where they were 31% of the population.[22]

The South developed an agricultural economy. It relied on commodity crops. Its planters quickly got more slaves. This was because its commodity crops were labor-intensive.[23]

Revolutionary Era[change | change source]

| Origins and Percentages of Africans imported into British North America and Louisiana (1700–1820)[24][25] |

Amount % (exceeds 100%) |

|---|---|

| West-central Africa (Kongo, N. Mbundu, S. Mbundu) | 26.1 |

| Bight of Biafra (Igbo, Tikar, Ibibio, Bamileke, Bubi) | 24.4 |

| Sierra Leone (Mende, Temne) | 15.8 |

| Senegambia (Mandinka, Fula, Wolof) | 14.5 |

| Gold Coast (Akan, Fon) | 13.1 |

| Windward Coast (Mandé, Kru) | 5.2 |

| Bight of Benin (Yoruba, Ewe, Fon, Allada and Mahi) | 4.3 |

| Southeast Africa (Macua, Malagasy) | 1.8 |

While there were some African slaves that were kept and sold in England,[26] slavery in Great Britain had not been allowed by statute there. In 1772, it was made unenforceable at common law in England and Wales by a legal decision. The big British role in the international slave trade continued until 1807. Slavery continued in most of Britain's colonies. Many rich slave owners lived in England and had a lot of power.[27]

In early 1775 Lord Dunmore, royal governor of Virginia, wrote to Lord Dartmouth. He wrote he was going to free slaves owned by Patriots in case they rebelled.[28] On November 7, 1775, Lord Dunmore issued Lord Dunmore's Proclamation which declared martial law.[29] He promised freedom for any slaves of American patriots who would leave their masters and join the royal forces. Slaves owned by Loyalist masters, however, were not going to be freed by Dunmore's Proclamation. About 1500 slaves owned by Patriots ran away and joined Dunmore's forces. Most died of disease before they could do any fighting. Three hundred of these freed slaves made it to freedom in Britain.[30]

Many slaves used the war to run away from their plantations. They would run into cities or woods. In South Carolina, nearly 25,000 slaves (30% of the total enslaved population) ran away, migrated, or died during the war. In the South, many slaves died, with many due to escapes.[31] Slaves also escaped throughout New England and the mid-Atlantic, joining the British who had occupied New York.

Slaves and free blacks also fought with the rebels during the Revolutionary War. Washington allowed slaves to be freed who fought with the American Continental Army. Rhode Island started enlisting slaves in 1778. Rhode Island promised money to owners whose slaves enlisted and lived to gain freedom.[32][33] During the course of the war, about one fifth of the northern army was black.[34] In 1781, Baron Closen, a German officer in the French Royal Deux-Ponts Regiment at the Battle of Yorktown, estimated the American army to be about one-quarter black.[35] These men included both former slaves and free blacks.

In the 18th century, Britain became the world's biggest slave trader. Starting in 1777, the Patriots made importing slaves illegal state by state. They all acted to end the international trade. However, it was later reopened in South Carolina and Georgia. In 1807 Congress acted on President Jefferson's advice and made importing slaves from other countries a federal crime, as the Constitution permitted, starting January 1, 1808.[36]

1790 to 1860[change | change source]

"Fancy ladies"[change | change source]

In the United States in the early nineteenth century, owners of female slaves could freely and legally use them as sexual objects. This is similar to the free use of female slaves on slave ships by the crews.[37]: 83

"Fancy" was a code word that meant the girl or young woman was able to be used for or trained for sexual use.[38]: 56 Sometimes, children were also abused like this. The sale of a 13-year-old "nearly a fancy" is documented.[39]

Furthermore, females who were able to become pregnant were supposed to be kept pregnant,[40] so they could make more slaves to sell. The differences in skin color found in the United States make it obvious how often black women were impregnated by whites.[41]: 78–79 For example, in the 1850 Census, 75.4% of "free negros" in Florida were described as mulattos, of mixed race.[42]: 2 Nevertheless, it is only very recently, with DNA studies, that any sort of reliable number can be provided, and the research has only begun. Light-skinned girls, who contrasted with the darker field workers, were preferred.[39][43]

Blacks who owned slaves[change | change source]

Some slave owners were black. An African former indentured servant who settled in Virginia in 1621, Anthony Johnson, became one of the earliest documented slave owners in the American colonies. This was documented when he won a civil lawsuit to own a man named John Casor.[44] In 1830, there were 3,775 black slave owners in the South. They owned a total of 12,760 slaves.[45] 80% of the black slave owners lived in Louisiana, South Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland.

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Wood, Peter (2003). "The Birth of Race-Based Slavery". Slate. (May 19, 2015): Reprinted from "Strange New Land: Africans in Colonial America" by Peter H. Wood with permission from Oxford University Press. ©1996, 2003.

- ↑ Walton Jr, Hanes; Puckett, Sherman C.; Deskins, Donald R., eds. (2012). "Chapter 4". The African American Electorate: A Statistical History. Vol. I. CQ Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-087289508-9.

- ↑ Smith, Julia Floyd (1973). Slavery and Plantation Growth in Antebellum Florida, 1821–1860. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0-8130-0323-8.

- ↑ McDonough, Gary W. (1993). The Florida Negro. A Federal Writers' Project Legacy. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-0878055883.

- ↑ Stephen D. Behrendt, David Richardson, and David Eltis, W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research, Harvard University. Based on "records for 27,233 voyages that set out to obtain slaves for the Americas". Stephen Behrendt (1999). "Transatlantic Slave Trade". Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00071-5.

- ↑ Introduction – Social Aspects of the Civil War Archived July 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, National Park Service.

- ↑ "A vision of Puerto Rico". 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Robert Wright, Richard (1941). "Negro Companions of the Spanish Explorers". Phylon. 2 (4).

- ↑ "St. Augustine, Florida founded". Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Richard Hofstadter, "White Servitude" Archived 2014-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, n.d., Montgomery College. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ 1.Deborah Gray White, Mia Bay, and Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Freedom on My Mind: A History of African Americans (New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2013), 59.

- ↑ "African Americans at Jamestown". National Park Service. February 26, 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

Arrival of "20 and odd" Africans in late August 1619, not aboard a Dutch ship as reported by John Rolfe, but an English warship, White Lion, sailing with a letters of marque issued to the English Captain Jope by the Protestant Dutch Prince Maurice, son of William of Orange. A letters of marque legally permitted the White Lion to sail as a privateer attacking any Spanish or Portuguese ships it encountered. The 20 and odd Africans were captives removed from the Portuguese slave ship, San Juan Bautista, following an encounter the ship had with the White Lion and her consort, the Treasurer, another English ship, while attempting to deliver its African prisoners to Mexico. Rolfe's reporting the White Lion as a Dutch warship was a clever ruse to transfer blame away from the English for piracy of the slave ship to the Dutch.

- ↑ Rein, Lisa (September 3, 2006). "Mystery of Va.'s First Slaves Is Unlocked 400 Years Later". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ↑ Knight, Kathryn (2010). "The First Africans". Historic Jamestowne. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

Nearing her destination, the slave ship was attacked by two English privateers, the White Lion and the Treasurer, in the Gulf of Mexico and robbed of 50-60 Africans.

- ↑ "Assessing the Slave Trade: Estimates". The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Donoghue, John (2010). Out of the Land of Bondage": The English Revolution and the Atlantic Origins of Abolition.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Higginbotham, A. Leon (1975). In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780195027457.

- ↑ Tom Costa (2011). "Runaway Slaves and Servants in Colonial Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Higginbotham, A. Leon (1975). In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780195027457.

- ↑ William M. Wiecek (1977). "the Statutory Law of Slavery and Race in the Thirteen Mainland Colonies of British America". The William and Mary Quarterly. 34 (2): 258–280. doi:10.2307/1925316. JSTOR 1925316.

- ↑ "Slavery in New York", The Nation, November 7, 2005

- ↑ Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves, 2003

- ↑ "The First Black Americans" Archived February 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Hashaw, Tim; US News and World Report, 1/21/07

- ↑ Gomez, Michael A: Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South, p. 29. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 1998.

- ↑ Rucker, Walter C. (2006). The River Flows On: Black Resistance, Culture, and Identity Formation in Early America. LSU Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8071-3109-1.

- ↑ Sandhu, Sukhdev (2011-02-17). "BBC – History – British History in depth: The First Black Britons". Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ↑ Padraic Xavier Scanlan, "Blood, Money and Endless Paper: Slavery and Capital in British Imperial History." History Compass 14.5 (2016): 218–230.

- ↑ Selig, Robert A. "The Revolution's Black Soldiers". AmericanRevolution.org. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- ↑ Scribner, Robert L. (1983). Revolutionary Virginia, the Road to Independence. University of Virginia Press. p. xxiv. ISBN 978-0-8139-0748-2.

- ↑ James L. Roark; et al. (2008). The American Promise, Volume I: To 1877: A History of the United States. Macmillan. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-312-58552-5.

- ↑ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619–1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1994, p. 73.

- ↑ Nell, William C. (1855). "IV, Rhode Island". The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution. Robert F. Wallcut. ISBN 9780557535286.

- ↑ Foner, Eric (2010). The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 205. ISBN 9780393066180.

- ↑ Liberty! The American Revolution (Documentary), Episode II:Blows Must Decide: 1774–1776. ©1997 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. ISBN 1-4157-0217-9

- ↑ "The Revolution's Black Soldiers" by Robert A. Selig, Ph.D., American Revolution website, 2013–2014

- ↑ Finkelman, Paul (2007). "The Abolition of The Slave Trade". New York Public Library. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ↑ Schafer, Daniel L. (2013). Zephaniah Kingsley Jr. and the Atlantic World. Slave Trader, Plantation Owner, Emancipator. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813044620.

- ↑ Manganelli, Kimberly Snyder (2012). Transatlantic spectacles of race : the tragic mulatta and the tragic muse. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813549873.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Johnson, Walter. "The Slave Trader, the White Slave, and the Politics of Racial Determination in the 1850s". Journal of American History. 87 (1). Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ↑ "She's Breeding Age: Dehumanizing Price For Getting Pregnant During Slavery". Black Then. 2018-05-02. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ↑ Phillips, Patrick (2016). Blood at the Root. A Racial Cleansing in America. W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393293012.

- ↑ Kingsley, Jr., Zephaniah; Stowell, Daniel W. (2000). "Introduction". Balancing Evils Judiciously : The Proslavery Writings of Zephaniah Kingsley. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813017334.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Guillory, Monique (1999), Some Enchanted Evening on the Auction Block: The Cultural Legacy of the New Orleans Quadroon Balls, Ph.D. dissertation, New York University

- ↑ Breen, T. H. (2004). "Myne Owne Ground" : Race and Freedom on Virginia's Eastern Shore, 1640–1676. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-0-19-972905-0.

- ↑ Conlin, Joseph (2011). The American Past: A Survey of American History. Cengage Learning. p. 370. ISBN 978-1-111-34339-2.

Bibliography[change | change source]

National and comparative studies[change | change source]

- Berlin, Ira. Generations of Captivity: A History of African American Slaves. (2003) ISBN 0-674-01061-2.

- Berlin, Ira. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Harvard University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-674-81092-9

- Berlin, Ira and Ronald Hoffman, eds. Slavery and Freedom in the Age of the American Revolution University Press of Virginia, 1983. essays by scholars

- Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. (2008) ISBN 978-0-385-50625-0.

- Blassingame, John W. The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South Oxford University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-19-502563-6.

- David, Paul A. and Temin, Peter. "Slavery: The Progressive Institution?", Journal of Economic History. Vol. 34, No. 3 (September 1974)

- Davis, David Brion. Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (2006)

- Elkins, Stanley. Slavery : A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life. University of Chicago Press, 1976. ISBN 0-226-20477-4

- Fehrenbacher, Don E. Slavery, Law, and Politics: The Dred Scott Case in Historical Perspective Oxford University Press, 1981

- Fogel, Robert W. Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery W.W. Norton, 1989. Econometric approach

- Foner, Eric (2005). Forever Free. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-40259-3.

- Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (2010), Pulitzer Prize excerpt and text search

- Franklin, John Hope and Loren Schweninger. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. (1999) ISBN 0-19-508449-7.

- Gallay, Alan. The Indian Slave Trade (2002).

- Genovese, Eugene D. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made Pantheon Books, 1974.

- Genovese, Eugene D. The Political Economy of Slavery: Studies in the Economy and Society of the Slave South (1967)

- Genovese, Eugene D. and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Fruits of Merchant Capital: Slavery and Bourgeois Property in the Rise and Expansion of Capitalism (1983)

- Hahn, Steven. "The Greatest Slave Rebellion in Modern History: Southern Slaves in the American Civil War." Southern Spaces (2004)

- Higginbotham, A. Leon, Jr. In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period. Oxford University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-19-502745-0

- Horton, James Oliver and Horton, Lois E. Slavery and the Making of America. (2005) ISBN 0-19-517903-X

- Kolchin, Peter. American Slavery, 1619–1877 Hill and Wang, 1993. Survey

- Litwack, Leon F. Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (1979), social history of how slavery ended in the Confederacy

- Mason, Matthew. Slavery and Politics in the Early American Republic. (2006) ISBN 978-0-8078-3049-9.

- Moon, Dannell, "Slavery", article in Encyclopedia of rape, Merril D. Smith (Ed.), Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004

- Moore, Wilbert Ellis, American Negro Slavery and Abolition: A Sociological Study, Ayer Publishing, 1980

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia W.W. Norton, 1975.

- Morris, Thomas D. Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619–1860 University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Oakes, James. The Ruling Race: A History of American Slaveholders. (1982) ISBN 0-393-31705-6.

- Ransom, Roger L. "Was It Really All That Great to Be a Slave?" Agricultural History, Vol. 48, No. 4 (1974) in JSTOR

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2007.

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2007.

- Scarborough, William K. The Overseer: Plantation Management in the Old South (1984)

- Schermerhorn, Calvin. The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 1815–1860. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015.

- Snyder, Terri L. The Power to Die: Slavery and Suicide in British North America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- Stampp, Kenneth M. The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South (1956) Survey

- Stampp, Kenneth M. "Interpreting the Slaveholders' World: a Review." Agricultural History 1970 44(4): 407–12. ISSN 0002-1482

- Tadman, Michael. Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

- Wright, W. D. Historians and Slavery; A Critical Analysis of Perspectives and Irony in American Slavery and Other Recent Works Washington, D.C.: University Press of America (1978)

State and local studies[change | change source]

- Fields, Barbara J. Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century Yale University Press, 1985.

- Jewett, Clayton E. and John O. Allen; Slavery in the South: A State-By-State History Greenwood Press, 2004

- Jennison, Watson W. Cultivating Race: The Expansion of Slavery in Georgia, 1750–1860 (University Press of Kentucky; 2012)

- Kulikoff, Alan. Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800 University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

- Minges, Patrick N.; Slavery in the Cherokee Nation: The Keetoowah Society and the Defining of a People, 1855–1867 2003 deals with Indian slave owners.

- Mohr, Clarence L. On the Threshold of Freedom: Masters and Slaves in Civil War Georgia University of Georgia Press, 1986.

- Mutti Burke, Diane (2010). On Slavery's Border: Missouri's Small Slaveholding Households, 1815–1865. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3683-1.

- Mooney, Chase C. Slavery in Tennessee Indiana University Press, 1957.

- Olwell, Robert. Masters, Slaves, & Subjects: The Culture of Power in the South Carolina Low Country, 1740–1790 Cornell University Press, 1998.

- Reidy, Joseph P. From Slavery to Agrarian Capitalism in the Cotton Plantation South, Central Georgia, 1800–1880 University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

- Ripley, C. Peter. Slaves and Freemen in Civil War Louisiana Louisiana State University Press, 1976.

- Rivers, Larry Eugene. Slavery in Florida: Territorial Days to Emancipation University Press of Florida, 2000.

- Sellers, James Benson; Slavery in Alabama University of Alabama Press, 1950

- Sydnor, Charles S. Slavery in Mississippi. 1933

- Takagi, Midori. Rearing Wolves to Our Own Destruction: Slavery in Richmond, Virginia, 1782–1865 University Press of Virginia, 1999.

- Taylor, Joe Gray. Negro Slavery in Louisiana. Louisiana Historical Society, 1963.

- Trexler, Harrison Anthony. Slavery in Missouri, 1804–1865 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1914) online edition

- Wood, Peter H. Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion W.W. Norton & Company, 1974.

Video[change | change source]

- Jenkins, Gary (director). Negroes To Hire (Lifedocumentaries, 2010); 52 minutes DVD; on slavery in Missouri

- Gannon, James (October 25, 2018). A Moral Debt: The Legacy of Slavery in the USA. Al-Jazeera. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

Gannon is a descendant of Robert E. Lee

Historiography[change | change source]

- Ayers, Edward L. "The American Civil War, Emancipation, and Reconstruction on the World Stage," OAH Magazine of History, January 2006, Vol. 20, Issue 1, pp. 54–60

- Berlin, Ira. "American Slavery in History and Memory and the Search for Social Justice," Journal of American History, March 2004, Vol. 90, Issue 4, pp. 1251–1268

- Boles, John B. and Evelyn T. Nolen, eds., Interpreting Southern History: Historiographical Essays in Honor of Sanford W. Higginbotham (1987).

- Brown, Vincent. "Social Death and Political Life in the Study of Slavery," American Historical Review, December 2009, Vol. 114, Issue 5, pp. 1231–49, examined historical and sociological studies since the influential 1982 book Slavery and Social Death by American sociologist Orlando Patterson

- Campbell, Gwyn. "Children and slavery in the new world: A review," Slavery & Abolition, August 2006, Vol. 27, Issue 2, pp. 261–85

- Dirck, Brian. "Changing Perspectives on Lincoln, Race, and Slavery," OAH Magazine of History, October 2007, Vol. 21, Issue 4, pp. 9–12

- Farrow, Anne; Lang, Joel; Frank, Jenifer. Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery. Ballantine Books, 2006 ISBN 0-345-46783-3

- Fogel, Robert W. The Slavery Debates, 1952–1990: A Retrospective (2007)

- Ford, Lacy K. (2009). Deliver Us from Evil. The Slavery Question in the Old South. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195118094.

- Frey, Sylvia R. "The Visible Church: Historiography of African American Religion since Raboteau," Slavery & Abolition, January 2008, Vol. 29 Issue 1, pp. 83–110

- Hettle, Wallace. "White Society in the Old South: The Literary Evidence Reconsidered," Southern Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the South, Fall/Winter 2006, Vol. 13, Issue 3/4, pp 29–44

- King, Richard H. "Marxism and the Slave South", American Quarterly 29 (1977), 117–31. focus on Genovese

- Kolchin, Peter. "American Historians and Antebellum Southern Slavery, 1959–1984", in William J. Cooper, Michael F. Holt, and John McCardell, eds., A Master's Due: Essays in Honor of David Herbert Donald (1985), 87–111

- Laurie, Bruce. "Workers, Abolitionists, and the Historians: A Historiographical Perspective," Labor: Studies in Working Class History of the Americas, Winter 2008, Vol. 5, Issue 4, pp. 17–55

- Neely Jr., Mark E. "Lincoln, Slavery, and the Nation," Journal of American History, September 2009, Vol. 96 Issue 2, pp. 456–58

- Parish; Peter J. Slavery: History and Historians Westview Press. 1989

- Penningroth, Dylan. "Writing Slavery's History," OAH Magazine of History, April 2009, Vol. 23 Issue 2, pp. 13–20, basic overview

- Rael, Patrick. Eighty-Eight Years: The Long Death of Slavery in the United States, 1777–1865. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2015.

- Sidbury, James. "Globalization, Creolization, and the Not-So-Peculiar Institution," Journal of Southern History, August 2007, Vol. 73, Issue 3, pp. 617–30, on colonial era

- Stuckey, P. Sterling. "Reflections on the Scholarship of African Origins and Influence in American Slavery," Journal of African American History, Fall 2006, Vol. 91 Issue 4, pp. 425–443

- Sweet, John Wood. "The Subject of the Slave Trade: Recent Currents in the Histories of the Atlantic, Great Britain, and Western Africa," Early American Studies, An Interdisciplinary Journal, Spring 2009, Vol. 7 Issue 1, pp. 1–45

- Tadman, Michael. "The Reputation of the Slave Trader in Southern History and the Social Memory of the South," American Nineteenth Century History, September 2007, Vol. 8, Issue 3, pp. 247–71

- Tulloch, Hugh. The Debate on the American Civil War Era (1998), ch. 2–4

Primary sources[change | change source]

- Albert, Octavia V. Rogers. The House of Bondage Or Charlotte Brooks and Other Slaves. Oxford University Press, 1991. Primary sources with commentary. ISBN 0-19-506784-3

- The House of Bondage, or, Charlotte Brooks and Other Slaves, Original and Life-Like complete text of original 1890 edition, along with cover & title page images, at website of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- An American (1855). Cotton is king: or, The culture of cotton, and its relation to Agriculture, Manufactures and Commerce; to the free colored people; and to those who hold that slavery is in itself sinful. Cincinnati.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Berlin, Ira, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowlands, eds. Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861–1867 5 vol Cambridge University Press, 1982. Very large collection of primary sources regarding the end of slavery

- Berlin, Ira, Marc Favreau, and Steven F. Miller, eds. Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Emancipation The New Press: 2007. ISBN 978-1-59558-228-7

- Blassingame, John W., ed. Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies.Louisiana State University Press, 1977.

- Burke, Diane Mutti, On Slavery's Border: Missouri's Small Slaveholding Households, 1815–1865,

- De Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America. (1994 Edition by Alfred A Knopf, Inc) ISBN 0-679-43134-9

- A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845) (Project Gutenberg Archived 2008-09-07 at the Wayback Machine), (Audio book at FreeAudio.org)

- "The Heroic Slave." Autographs for Freedom. Ed. Julia Griffiths Boston: Jewett and Company, 1853. 174–239. Available at the Documenting the American South website.

- Frederick Douglass My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) (Project Gutenberg Archived 2008-10-12 at the Wayback Machine)

- Frederick Douglass Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892)

- Frederick Douglass Collected Articles Of Frederick Douglass, A Slave Archived 2004-10-14 at the Wayback Machine (Project Gutenberg)

- Frederick Douglass: Autobiographies by Frederick Douglass, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Editor. (Omnibus of all three) ISBN 0-940450-79-8

- Litwack, Leon Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery. (1979) Winner of the 1981 National Book Award for history and the 1980 Pulitzer Prize for History.

- Litwack, Leon North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790–1860 (University of Chicago Press: 1961)

- Document: "List Negroes at Spring Garden with their ages taken January 1829" (title taken from document)

- Missouri History Museum Archives Slavery Collection

- Rawick, George P., ed. The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography . 19 vols. Greenwood Publishing Company, 1972. Collection of WPA interviews made in the 1930s with ex-slaves

More reading[change | change source]

Scholarly books[change | change source]

- Baptist, Edward E. (2014). The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00296-2.

- Beckert, Sven (2014). Empire of Cotton: A Global History. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-35325-0.

- Beckert, Sven; Rockman, Seth, eds. (2016). Slavery's capitalism : a new history of American economic development. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812248418.

- Forret, Jeff (2015). New directions in slavery studies : commodification, community, and comparison. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807161159.

- Johnson, Walter (2013). River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674045552.

- Schermerhorn, Calvin (2015). The business of slavery and the rise of American capitalism, 1815-1860. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300192001.

Scholarly pages[change | change source]

- Turner, Edward Raymond (1912). "The First Abolition Society in the United States". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 36: 92–109.

- Singleton, Theresa A. (1995). "The Archaeology of Slavery in North America". Annual Review of Anthropology. 24: 119–140. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.001003.

- McCarthy, Thomas (December 2004). "Coming to Terms with Our Past, Part II: On the Morality and Politics of Reparations for Slavery". Political Theory. 32 (6): 750–772. doi:10.1177/0090591704268924. S2CID 32786606.

- Lindsey, Treva B.; Johnson, Jessica Marie (Fall 2014). "Searching for Climax: Black Erotic Lives in Slavery and Freedom". Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism. 12 (2): 169+. Retrieved March 25, 2018.[permanent dead link]

Oral histories and autobiographies of ex-slaves[change | change source]

- Goings, Henry (2012). Schermerhorn, Calvin; Plunkett, Michael; Gaynor, Edward (eds.). Rambles of a Runaway from Southern Slavery. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813932408.

- Hurmence, Belinda, ed. (1989). Before Freedom When I Just Can Remember: Twenty-seven Oral Histories of Former South Carolina Slaves. Blair. ISBN 978-0-89587-069-8.

- Hurmence, Belinda, ed. (1990). Before Freedom: Forty-Eight Oral Histories of Former North & South Carolina Slaves. Mentor Books. ISBN 978-0-451-62781-0.

- Hurmence, Belinda, ed. (1990). My Folks Don't Want Me to Talk about Slavery: Twenty-One Oral Histories of Former North Carolina Slaves.

- Hurmence, Belinda, ed. (1997). Slavery Time When I Was Chillun. G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0399231940.

- Hurmence, Belinda, ed. (1994). We Lived in a Little Cabin in the Yard: Personal Accounts of Slavery in Virginia. Blair. ISBN 978-0895871183.

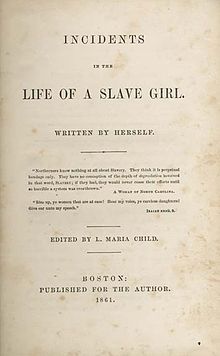

- Jacobs, Harriet Ann (1861). Child, L. Maria (ed.). Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself (PDF). Thayer & Eldridge.[permanent dead link]

- Johnson, Clifton H. (1993). God Struck Me Dead, Voices of Ex-Slaves. Pilgrim Press. ISBN 978-0-8298-0945-9.

Literary and cultural criticism[change | change source]

- Ryan, Tim A. Calls and Responses: The American Novel of Slavery since Gone with the Wind. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008.

- Van Deburg, William. Slavery and Race in American Popular Culture. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Documentary movies[change | change source]

- Kovgan, A. Ray, J. Browne, K. (Director). (2008). Traces of the Trade [Video file]. California Newsreel.[1]

Other websites[change | change source]

- "How Slaves Built American Capitalism", CounterPunch, December 18, 2015

- "Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936–1938", Library of Congress

- "Voices from the Days of Slavery", audio interviews of former slaves, 1932–1975, Library of Congress

- Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

- "Slavery and the Making of America", WNET (4-part series)

- "Slavery in the United States", Economic History Encyclopedia, March 26, 2008

- North American Slave Narratives, Documenting the American South, Louis Round Wilson Library

- "Slavery and Civil War digital collection", scanned original documents, Grand Valley State University

- "How Slavery Really Ended in America", New York Times Magazine, April 1, 2011

- "The Color Line", 6-page lesson plan for high school, Zinn Education Project

- "The First Slaves", 15-page teaching guide for high school, Zinn Education Project

- "Not Your Momma's History", historical education about slavery and the 18th and 19th-century African experience in America

- "Harvesting Cotton-Field Capitalism: Edward Baptist's New Book Follows the Money on Slavery", The New York Times, October 3, 2014

- "5 Things About Slavery You Probably Didn't Learn In Social Studies: A Short Guide To 'The Half Has Never Been Told'", HuffPost, October 25, 2014

- 9 Facts About Slavery They Don't Want You to Know

- "Slavery" maps in the U.S. Persuasive Cartography collection, Cornell University Library

- The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database has information on almost 36,000 slaving voyages

- ↑ "Traces of the Trade". Traces of the Trade. Retrieved 2019-03-19.