Ray Davies has now been famous for close on half a century, and yet the experience seems to have changed him hardly at all. He still lives barely a mile from where he was born (Fortis Green, in north London). He is still friends with people he knew at school. In a pub, he can still "disappear", a talent that enables him always to drink his pint in peace ("it's a pleasant surprise for people, when they find out who I am, and what I've done"). Then there is his interview technique. Davies dislikes doing interviews, and gives relatively few, but if you get lucky and find yourself alone with him, the surprise is that he answers every question with so little guile. Naturally, this is thrilling; I'm a journalist, after all. But it's also unnerving. You expect men of his generation and class to be blithe, and a little butch. He is neither. Quiet and self-deprecating, he has trouble, sometimes, meeting my eye. Is he shy? "Yes, immensely," he says, exhaling. It's as if he is relieved that I have spotted this.

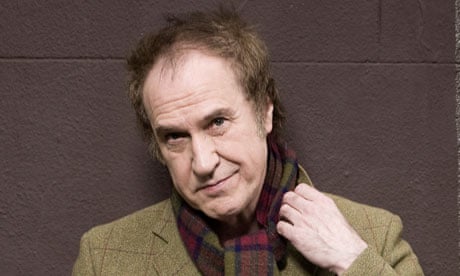

We meet at Konk, the Kinks' recording studios. It's a nondescript building in a nondescript street in a down-at-heel patch of Hornsey: straight out of one his songs. A part of me is, I guess, still expecting Davies to be wearing a paisley cravat or, even better, velvet trousers. But when he appears, deep in the bowels of the building, he is in a baggy navy sweatshirt, jeans and a pair of white trainers as big as barges. He is thin, slightly stooped, and his once luxuriant (and now rather unexpectedly brown) hair has retreated over time so that his famous forehead appears higher than ever. Until he grins, and you catch sight of the old gap-toothed smile, he could be anyone: a university lecturer, an electrician. I can no more imagine him high-kicking on Top of the Pops than I can myself. How, I wonder, does he ever screw up enough courage to propel himself on stage? "Well," he says. "There's an element of voodoo attached to what I do. It's something that happens: a kind of energy. I remember playing Glastonbury, the year before last. The acoustic tent. It was raining. I didn't want to play. I was so miserable. Worse than I am now! I didn't even get changed. I put my wellingtons on, and I just walked on, and from that moment something happened. It was one of the best shows I've ever done."

Motivation, he admits, can be a problem. Davies is curating this year's Meltdown on the South Bank, and though he's pleased to be doing so – his line-up, which includes Madness, Harrison Birtwistle and Anna Calvi, is quirky, stellar and enjoyably English – he nevertheless had to sell the idea to himself before he was able to sign on the dotted line. "Whenever I'm asked to do something, I have to motivate myself by coming up with a vision of what it will be like. I'd heard it was a big job. Patti Smith, one of my predecessors, exhausted herself doing it." It was the fact that this Meltdown forms part of the celebrations marking the 60th anniversary of the Festival of Britain that swung it. Davies visited the festival – he was seven – and still remembers it vividly. "My dad took me. It was so different. So futuristic." The Skylon!" He frowns. "What was the Skylon supposed to do exactly?" I tell him that, so far as I am aware, it didn't do anything. The frown takes a while to fade.

Unlike most people, who think of the 50s as rather brown, Davies looks back with fondness. "I was born after the war," he says. "So I never saw aeroplanes overhead. But I used to play on bombsites. All the kids did. Iremember the 50s as sunny and bright. My dad was a market gardener, so we always had lots of veggies. I don't remember doing without [rationing did not end until 1954]. I always seemed to get what I wanted." Was this because he had six older sisters? I bet they spoiled him. "No, I don't think it was that. I just got everything I wanted. I don't know why."

Did his sisters seem sophisticated? "Boyfriends always came to the house. I was very interested to meet them, to listen to their music. We used to watch them dancing in the front room. It was magical. I was a serious child, quite quiet, but I enjoyed picking up parts of their culture: big band music, romantic songs from during the war."

Some of his peers kicked against this sort of thing – sentimental ballads, the prettified shackles of tradition – but Davies was always a little out of kilter with the mood. When he went to art school in the early 60s, for instance, he could feel that "culture was going through a radical change… I mean, people went off to be artists rather than to get proper jobs. Previously, art school had been for the upper and middle classes. Then working-class culture started coming in: in the theatre, in films, in music. There was this feeling that art was moving in that direction too. John Bratby [leading exponent of what David Sylvester called the "kitchen sink" school] was the painter everyone was talking about." Did Davies, product of a secondary modern, find this liberating? No, he did not. "I wanted everything to be as it was," he says, with a kind of yelp. "I liked the Old Masters. Russian icons. That's how I wanted to paint."

It seems odd, then, that on leaving art school he decided to become a rock singer (he formed the Kinks with his guitarist brother, Dave, in 1964), though his critics would argue that his achilles heel as a songwriter has always been his tendency towards nostalgia and whimsy. "Yes, it's a little miracle, really," he says, quietly. Not that global fame was ever his goal. "I remember when we made our first hit record. My producer and I were walking down Oxford Street, and he said: 'This will be the last time you walk down this street without people talking to you.' I asked him why. He said: 'This is going to be No 1.' I didn't really understand what he meant. I thought I'd remain anonymous – and I was right, in a way. I knew a famous actress once, I mean world-famous, and she told me she could turn it [the ability to attract attention] on and off. We went to a bar, and she proved to me that you can go somewhere where there are crowds, and not be noticed. Some people like tabloid culture. They like to be seen by everybody. But I've been reserved about it. There are still people who say: 'Ray who?' and that's OK."

A few years ago, when he was still touring with the Kinks, the band was due to play in Providence, Rhode Island. Davies arrived late. When he turned up at the stage door, no one recognised him.

Didn't fame change his relationships with his family and his friends? When "You Really Got Me" went to No 1, he was only 20. "I wasn't aware that it did. My sisters were supportive. I didn't lose friends, though I did lose touch with a few. Recently I've been getting back in touch again. They turned up at my show, I took their numbers, and we emailed. It's nice. They knew me before I did what I do. So when you sit down, they know you for what you really are, and sometimes it cuts through all the stuff with the music."

The chief shock associated with fame was realising that being creative would take up only 5% of his time. "I had to find out about contracts, how all the machinery works. I hate it to this day. I wasn't ready for it. We were only the second, maybe the third, generation of British rock'n'rollers. It was new territory. These days you can do a degree in how to be in the music business. But we were virgins. We're still fighting for royalties we haven't been paid." Does this get him down? "Yes. It becomes overwhelming. I try not to think about it."

Davies has always said his songs are peopled by characters, and that it is imagining the lives of these characters that gives his lyrics their heartbeat: "I write songs about people, and I happen to feel that the suburbanite kind of person who's not much noticed is quite interesting." Everything goes into these songs. "I had a partner once, and when we broke up, she said: I've never understood it. I've listened to all the music you've written while I've been living with you, and I never would have thought you'd think of anything as nice as that, that you could be as sensitive as that." He is smiling, but he doesn't look particularly happy. "It's not that I write in secret. I'm not an Emily Dickinson. But it's a private world for me… not so much now, I'm more open these days. But when I started out I was shy about it because I suddenly had ideas that people were actually listening to. It was quite a big thing."

He doesn't disdain the way people connect him, thanks to songs like "Sunny Afternoon" and albums like The Village Green Preservation Society, to a kind of Englishness, but nor is he certain where this fondness for writing about stately homes and strawberry jam comes from. Perhaps, I suggest, it's to do with homesickness: some years he wasn't in the country for more than a few days at a time. He thinks about this. "I wasn't aware I was homesick. I thought that was my life: the road, the hotel rooms, the diners. It's only since I was forced to stay in England over the last few months [last year he fell ill with a blood disorder, and was not allowed to fly] that I realised I might have been homesick." He thinks some more. "All my most famous songs were written in England, but maybe you're right, and there is an exile inside me."

His other spur to creativity is – or was, until the Kinks split in 1996 – his younger brother, Dave. The story goes, for all you Freudians out there, that all was well in little Ray's world until, in 1947when he was three and a half, he saw, out of the corner of his eye, a screaming baby whose name was David. When they were in the band, their rows were legendary: brutal and prolonged. But a few weeks ago Dave gave an interview in which, once he'd done listing Ray's faults (meanness, vanity, narcissism, emotional greed), he said: "I love him to death." So is their feud on or off? Davies smirks. "He's my little brother, what can I say? Some people say he's a jumped-up upstart, but I say: take him as you find him. He feels it's his duty to have a swipe at me occasionally, and that's all right. We've come a long way from the crib. Only, sometimes, he can be negative for the sake of being negative. I've had to bang my head against the wall so many times with him. He is such a bright lad but he lets himself down.

"When we were together it was aggressive, violent, powerful, but we triggered off each other. We don't see each other much, but this morning I found two songs we recorded together at my house on my computer. It's unforgettable, his sound. I might develop them. In some ways he is more adult than I am. I remember when my mother died, I was in New York cutting a record, and he was by her bedside, and he rang me and he said: 'She's dead.' I said: 'Will you check?' And he said: 'I've checked already.' He took care of all the things I should have taken care of. He's more grounded than me, but in other ways… he's out there with the fairies."

He laughs. "I won't read the piece you mention, though, because I'll get upset."

Davies has been married three times, and he has four daughters (two by his first wife, one by Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders, and one by his third wife). Does he have a girlfriend? "I'm in between girlfriends. I'm easy to love, and impossible to live with." Does that mean he's better on his own? "There's nothing like having a good partner. You want someone you can go home to and say: I had a crap day. It doesn't help the day, but you've got someone to say it to.I'm rationing relationships in the sense that I want the next one to be a good one, a sincere one." What about his daughters? "That's the one thing I really regret about my career, not having been with my kids more." But are things better now? "Not really. I have a daughter in Ireland. She's 14. I speak to her when I can. I haven't seen her in nearly a year, which is terrible. I was going to go at Christmas, but then I got sick. I miss her. I could see her if I wanted to, it's just…" His voice trails off for a moment.

"The other ones I had early on. One is married and lives in Hong Kong. The other one lives in Kent. They're all right. I had one daughter from another relationship [this is the daughter by Hynde, whom he did not meet until she was grown up] and she texted me this morning, and I'll text her back later. Do they think of their father in an oh-we-despair-of-dad kind of way? He doesn't answer this.

"I wish I could have sustained a normal married relationship because seeing my friends who've been with the same partner… My friend Patrick has been with the same woman since he was at school, and I envy him that. He showed me pictures of his family get-togethers, and there's a balance there. It's an interesting phenomenon, this [being a father to] half-sisters thing. You have a child with somebody, and there's someone else in the background you're not supposed to talk about. I would like to feel more comfortable about it."

Oh dear. He seems so… subdued. "No, I'm not!" he says. So what makes him happy? "It doesn't take much: seeing other people happy, doing work that makes me think 'I had one moment of originality today'. I believe that creativity is a gift, and that everybody's got the ability to be creative. I do these songwriting courses [for the Arvon Foundation], and it's so great." This is generous. I can't imagine certain of his peers teaching thwarted teachers and postmen to write lyrics. "No, it's not generous! It helps me as well. Writing can be quite lonely."

In the moments before I leave – he must put in a phone call to the US, where his album See My Friends has just been released – we talk about the blank screen, and the way it must be filled, day after day; the way he always wonders, even after all these years, whether he can pull off the same trick one more time. "It's horrible, isn't it?" he says, softly. "The insecurity. The way it drives you." His voice is low, but very kind.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion