Trump Fails the QAnon Test

The president’s refusal to condemn the conspiracy theory was a shock, but not a surprise.

President Donald Trump likes to dabble in conspiracy theories, and he does not like to contradict his base. So it should come as no surprise that the president tonight refused to denounce the warped conspiracy-theory movement known as QAnon, which posits that a global cabal is torturing children, and which exalts Trump as its savior.

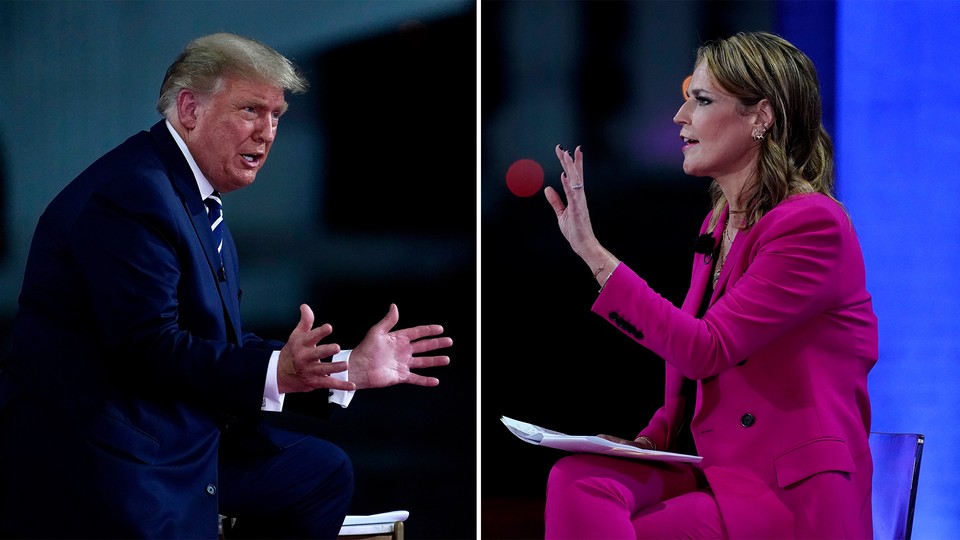

Yet if Trump no longer has the power to surprise, he still has the power to shock. He proved that once again tonight, when NBC’s Savannah Guthrie confronted him about Q during the network’s town hall, as Trump first claimed not to know what QAnon was and then voiced sympathy with its supposed central tenet. “What I do hear about it is they are very strongly against pedophilia, and I agree with that,” the president said. “I do agree with that.”

“But they’re not a satanic cult?” Guthrie asked.

“I don’t know that,” Trump replied.

The question—“Can you once and for all denounce QAnon in its entirety?”—had been a layup for Trump, an opportunity for him to signal to middle-of-the-road voters that he is not, in fact, crazy, and to the conspiracy theorists of America that they should give up this delusion. It was remarkably similar to the shot Trump had in the first debate to unequivocally condemn white supremacy, which resulted in another infamous air ball. (Pressed on that by Guthrie tonight, Trump quickly denounced white supremacy and then quickly pivoted to railing against antifa.)

This was not the first time Trump has praised QAnon, which the FBI has called a domestic terrorism threat. “I heard these are people that love our country,” he said in August. By one count, he has amplified Twitter accounts that promote QAnon more than 200 times. But the question tonight came in front of an enormous audience, and once again, the president could not bring himself to criticize a group, however large or small, that provides him with loyal support. Trump’s opponent, former Vice President Joe Biden, had no such trouble denouncing QAnon last month; he called the movement “embarrassing” and “dangerous,” suggesting that its followers take advantage of the mental-health benefits in the Affordable Care Act.

It’s not clear how far the QAnon conspiracy has spread in the U.S., but it is spreading deeper into the nation’s halls of power. A number of Republican congressional candidates are followers of QAnon, and one of them, Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, is virtually assured of winning a seat in the House this fall. Hours before Trump’s town hall, Senator Kelly Loeffler of Georgia—who has tied herself closely to the president—enthusiastically accepted Greene’s endorsement in her bid for a full six-year term.

Nor was QAnon the only conspiracy theory Trump hedged on during the town hall, held as a quasi-substitute for the second presidential debate, which was canceled after the president fell ill with COVID-19. He dodged when Guthrie asked why he had retweeted a tweet promoting the absurdity that Joe Biden had ordered the death of the Navy SEALs who took out Osama bin Laden. “That was a retweet. That was an opinion of somebody,” Trump protested. “I don’t get it,” Guthrie replied. “You’re the president. You’re not someone’s crazy uncle.”

It’s tempting to conclude that Trump simply doesn’t know the difference. But that would be overly charitable to the president. He’s a politician who caters to his base, who doesn’t dare alienate the people who put him in office, and who he needs to salvage his chance at a second term. In 2016, that base included people who believed that President Barack Obama was born in Kenya and had gained the White House illegitimately. Once in office, Trump’s base came to believe there was a “deep state” conspiracy against the president. And now that base of Americans whom Trump won’t cross includes the followers of QAnon.