The idea of Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown, Sam Cooke and Malcolm X sitting around a hotel room in the mid-1960s to discuss matters of religion, politics and race sounds like the basis for a work of fiction, and indeed, it found life in the 2013 stage play One Night in Miami by Kemp Powers, who went on to adapt his script for a 2020 feature film directed by Academy Award–winner Regina King.

But it’s also a concept that comes with the “based on a true story” tag, a surprising twist given the accomplishments of the immensely famous men involved, and the secrecy of their fateful meeting that endured even after so many stones of their individual lives had been overturned.

The icons gathered to watch Ali claim the heavyweight boxing championship

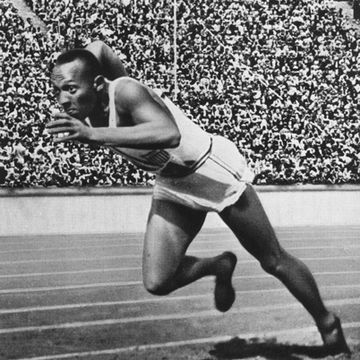

The story begins with the convergence of the quartet at the Miami Beach Convention Hall on February 25, 1964, where Ali—then still known by his birth name of Cassius Clay—challenged Sonny Liston for the heavyweight boxing championship of the world.

Cooke, the ground-breaking gospel-turned-pop singer and record label owner, was there to cheer on his good friend from a ringside seat, as was Malcolm X, the controversial Nation of Islam minister who all but shadowed Ali in the weeks leading up to the event. Brown, the unstoppable and outspoken NFL running back, was close by to provide commentary as part of the bout’s radio broadcast team.

The fight is remembered as the night Ali “shook up the world” with his thorough whupping of the heavily favored Liston, who surrendered the title with his refusal to continue into the seventh round, though the record of what happened next is a little murkier.

They eschewed a big celebration for a quiet hotel room gathering

According to Jim Brown: Last Man Standing, the football star was itching to get to an after-party at the Fontainebleau hotel but was dissuaded by the new champ, who wanted to talk at a “little Black hotel.”

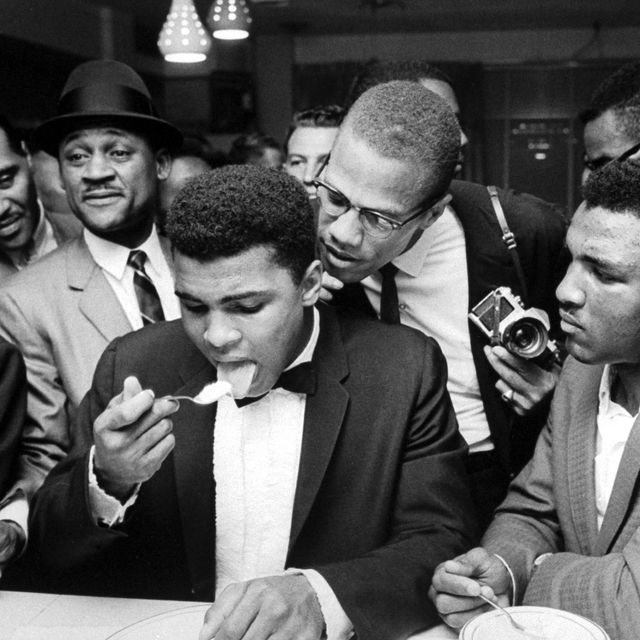

Ali: A Life says the boxer’s sponsorship team attempted to pull together a party at a different spot, while Ali and Malcolm X went off to celebrate the big win over bowls of ice cream at a soda fountain.

Eventually, Ali, Brown and Cooke all ended up in Malcolm X’s room at the Hampton House Motel, away from Miami Beach’s segregated venues, for a night of discussion with a group that included Ali biographer Howard Bingham and several Nation of Islam members.

What transpired behind closed doors is largely lost to time, though it’s known that more ice cream was consumed. Both Ali: A Life and Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke mention the host’s suggestion that it was time for the notoriously talkative Ali to “stop spouting off and get serious,” while the first book also notes that the tired champ fell asleep at one point, before heading back to his rented home sometime after 2 in the morning.

The motel room rendezvous would likely be even more of a historical footnote were it not for the effect it seemingly had on Ali, who livened up a press conference the following day by confirming the whispers that he was a Muslim. And its memory would certainly be less poignant without the harsh reality that soon intruded, with both Malcolm X and Cooke killed less than a year later.

Powers sought to strip his subjects of their fame

Fast-forward four decades and across the country to Los Angeles, where Powers was making a living as a journalist and editor. The writer drew attention for the 2004 publication of The Shooting: A Memoir, in which he recalled a horrific accident from his teenage years that left his best friend dead, but he was already stewing on another project after coming across a snippet about the post-fight get-together of Ali, Cooke, Brown, and Malcolm X.

To Powers, who counted each of the four civil rights-era icons as a personal hero, the discovery that they were friends and holed up in a room, bouncing ideas off one another, was equivalent to stumbling upon the existence of a “Black Justice League of America.”

He set about piecing together the events of that night and digging deeper into their backstories, leaving him ready to write when the artistic director of L.A.’s Rogue Machine Theatre asked him to submit a script for production. But while Kemp was game for imagining what his heroes may have said, the long shadow of fame they cast proved problematic to the creative process.

“It didn’t really begin to sing until I moved away from all of the iconography and deconstructed who these guys were as men, and how that could aid (or taint) a friendship,” he wrote just prior to the One Night in Miami premiere in June 2013. “Suddenly, they became relatable... This play is simply about one night, four friends and the many pivotal decisions that can happen in a single revelatory evening.”

King saw it as a “love story”

A success, One Night in Miami moved to theaters around the country and across the Atlantic, along the way picking up three L.A. Drama Critics Circle Awards and an Olivier Award nomination.

The script also caught the attention of King, who’d intended to focus on a “love story” for her directorial debut but instead found herself drawn to the emotion and vulnerability apparent in Kemp’s work. “I saw every Black man that I know and love in these men,” she told Variety. “And I knew that it was my job to bring it to life.”

Once again, a harsh reality left its imprint on proceedings, with the racially infused strife of 2020 that included the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd impacting everyone involved before production was complete.

But the tragedies also gave the project new relevance while showing why its premise remains so timelessly powerful, a story of four buddies sharing their grievances, hopes and reflections on what it means to be a Black person in America, drawn from a real-life session that took place more than a half-century ago but just as easily could have happened yesterday.