It was June 1984 in a Vietnamese restaurant in Pimlico. I had taken my mother to the revival of On Your Toes for her birthday treat and was now feeding her her very first crispy duck pancakes. I was 22 and living in a bedsit off Notting Hill Gate.

I had never formally come out. It would have seemed a little redundant. I’d been a wildly camp little boy, much given to dressing up even for school, and an aesthetically obsessed teenager who spent all his spare time on music and acting. The closest I ever came was handing my mother the manuscript of my first novel, The Aerodynamics of Pork, a few weeks earlier. Still in print, for the charitable or curious, this is a wild fantasy in which almost every character has a lesbian or gay secret.

“So?” I finally asked, when she didn’t bring it up. “What did you make of the book?”

“It was lovely,” she said unconvincingly. “Funny and naughty and oh so sad. Now I’ll think every policewoman I see is a lesbian. Your father read it, too.”

I hadn’t counted on this. My father’s preferred reading veered wildly between two-volume lives of Victorian archbishops and thrillers with submarines on the cover. I loved him, he was always very kind to me, but we were not close, not confessional in the way I had always been with my mother. I would sit at the foot of her bed to talk as she rubbed in her night cream. I never did the equivalent with him. She saw my consternation. “It will help him come to terms with himself,” she added.

Twenty-three years earlier, while heavily pregnant with me and preparing to move the family from Governor’s House, at HMP Camp Hill on the Isle of Wight, to the equivalent mansion in Wandsworth, she had taken it upon herself to tidy out my father’s desk. She came upon a sheaf of letters tucked away in a drawer, saw the first began “My darling Michael” and gleefully sat down to read, assuming them to be from some girl he had never mentioned. Only they were from his oldest school friend, who had gone to Oxford with him, and fought alongside him in the war. They had been best man to each another.

“But maybe they were just very close?” I suggested. “Men back then often had deep romantic friendships. Darling didn’t always mean–”

She cut me off, espresso cup wobbling. It was plain from the letters, she said, that my father had shown the man a passion he had never shown her. She burnt them – terrified, in such an era, that their discovery would see him arrested and sent to one of the prisons his colleagues governed. In the early 1960s, discovery would have spelled a ruin as complete as in the time of Oscar Wilde.

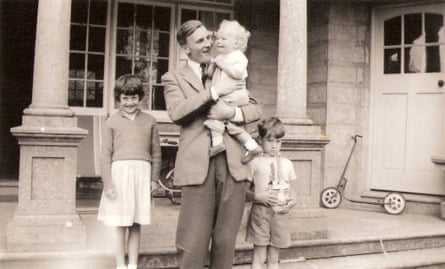

Her next responses were stranger and more damaging. She never told him what she had discovered. She simply never let him in her bed again – encouraging the adoption of separate beds under a single hypocritical quilt, and then separate bedrooms. Thinking herself, as the wife and daughter of prison governors, well versed in such sordid matters, she assumed the revelation meant he was a paedophile, so thereafter saw to it that he was never left alone with any of us. I did not have a single private moment with my father until my teens, when he retired, and I began to have tentative encounters with this near stranger now present at weekday breakfasts.

She was happy that the story excited me. Suddenly I understood my father. Suddenly his emotional inhibition and his complete lack of demonstrative behaviour made sense. It was only as I waved her off on her train back to Winchester the following morning that I realised her gladness had a completely different meaning to the one I’d clumsily assumed. She didn’t realise she was telling me a horror story of stifled love and a marriage built on lies. She honestly believed, having read my novel of tangled gay love lives, that she was offering me hope that I, too, might yet meet a good Christian woman like her, who would burn my past and mend my ways.

I don’t for one moment think of my father as having been gay. That term simply doesn’t hold for the men of his ambiguously homosocial generation. I think he had one great love but that he believed it was impossible and immature. Psychologically, he was suited to becoming a bachelor history don, harbouring secret favouritisms, and cared for by a devoted housekeeper, but he held it was his Christian duty to marry and have children. So that’s what he did.

I have letters from my parents’ courtship in early 1950s Durham, where he was working at the prison. It’s plain that at some point in the relationship there was a muffled crisis brought on, I think, by his attempting to confess everything about himself and by her inability, in her ferociously maintained innocence, to deal with it. And I don’t think the impulse to infidelity will have once entered his mind. Ironically, by never telling him what she had discovered, she maintained him in the belief that he had indeed been saved by her. And, though wildly unsuited in many ways, they found a kind of companionate love, especially once an empty nest removed any pressure to function as a traditional couple.

But in that Pimlico restaurant in 1984, after two decades of believing myself a family freak and someone living outside the law, making my legs and arms and scalp bleed from eczema as my guilt and fear erupted through my skin, I had been abruptly awarded the validation that comes from genetic inheritance.

I was very like my father in so many ways. I favoured him physically but I think we were alike emotionally as well, given to sly observation and irony in situations where my two older brothers would respond with open anger. Like him, I would always choose solitude over a crowd, a book over a party. Like him, I learnt to hide my social reluctance with courtesy and correctness. So learning that he might have been like me, had he only been born 40 years later, made me understand, pity and warm to him.

Yet, like my mother, I found I could never tell him what I had learnt. I showed my new love in code instead, in books and bottles of whisky and in invitations to visit me in my new life in Cornwall. He was deeply supportive of my two long-term domestic relationships, settling my share of the family silver just as if I had got married, and doing his best to love my partners.

Man in an Orange Shirt is not about Pippa and Michael Gale. I’ve written versions of them repeatedly in my novels. But it has at its heart that terrible scene of discovery and letter-burning. However, in the drama I’ve imagined how differently things might have played out had my mother confronted my father and, like so many couples of their generation, achieved a terrible, respectable compromise. Writing it, I gave voice to my father’s stifled passion and pain, but also came to understand the impossible burden my poor mother took on in marrying him.

- Man in an Orange Shirt begins on BBC2 at 9pm on 31 July

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion