It is intended to be a world-leading research facility that will house some of the UK’s greatest collections of historical, botanical and zoological samples. Millions of ancient mosaics and pieces of sculpture, rare plant specimens and fossil remnants will be taken from the British Museum, the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew and the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London and rehoused at Reading University’s Thames Valley Science Park in Shinfield, Berkshire.

London’s ageing buildings, crumbling storage space, and soaring land prices mean a move beyond the M25 is the only realistic way to protect the capital’s swelling backroom collections of scientific and cultural treasures while improving researchers’ access to them, say senior museum staff. The total price-tag for the venture could top half a billion pounds.

But this vast rehousing project has not been universally welcomed. Indeed, it has proved to be highly controversial among some groups, with researchers denouncing the proposals as acts of “cultural and scientific vandalism”. Others have accused management at Kew and the NHM of bullying staff into accepting the plan to rehouse collections.

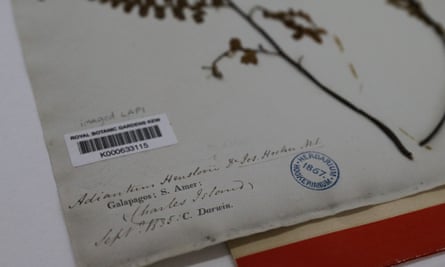

At Kew, a petition, signed by more than 15,000 people, calls for management to abandon its plan to rehouse the garden’s 170-year-old herbarium at the new science park. Signatories include Sir Ghillean Prance, a former director of Kew, who told the Observer that he was dismayed by the idea of moving the collection, which contains more than 7m specimens of dried, pressed plants gathered from around the world.

“The herbarium is one of the world’s oldest and rests in the middle of Kew where there is a crucial interaction between the collection and the rest of the botanic gardens. At present the place buzzes with botanists and other researchers from across the world who come here to take advantage of this critically important plant collection. Take away the herbarium and put it in an out-of-the-way location and you will ruin it.”

Others argue that the relocation would interfere with the work of scientists, who are already stretched in their bids to identify and conserve plants in the face of increasing biodiversity loss across the globe. “This is one of the most important herbariums in the world,” added Prance. “Specimens here include originals from which plant species are named. It should be kept at the heart of Kew.”

Managers at Kew reject these criticisms, however. They say the current herbarium building has been already been expanded six times since it was first used to house the gardens’ plant collection in 1856. However, any new building would face severe construction restrictions because Kew is designated a world heritage site. In addition, there is a growing risk of flooding from the adjacent River Thames, while the current building also faces of risks of future fire – similar to the one that destroyed the National Museum of Brazil in 2018.

“Our plans for a modern and state-of-the-art science facility ... will not only strengthen Britain’s position in botanical research and innovation but also ensure the secrets of these specimens can be unlocked in future,” Prof Alexandre Antonelli, Kew’s director of science, told the Observer last week.

At present, the public cannot visit the herbarium, which is a dedicated research facility. But once its plant collection is moved to the science park, the building will be redeveloped as a science quarter, a public display of Kew’s prime specimens, including those donated by Charles Darwin, added a spokesperson.

A decision on whether to move the Kew herbarium – which could cost £200m and take a decade to complete – is to be taken early next month when the gardens’ board of trustees will vote on the proposed relocation.

By contrast, a decision to move part of the NHM’s collections to Shinfield has already been agreed. A total of £200m is to be spent on the new facility, which is awaiting planning permission, and 28m museum specimens will be shifted there. These will include everything from microscopic samples of ancient crustacea to pieces of some of world’s largest creatures, including whales. Data from these specimens will be digitised and shared with scientists across the globe.

“Over the past 250 years, we have built up a collection of around 80m specimens, the remains of our planet’s vast array of lifeforms. However, not all of them are being stored in the best conditions today. Moving some to the new science park will ensure they are better preserved and also more easily accessed by researchers,” said a museum spokesperson.

after newsletter promotion

But the plan, although approved and financed, has been denounced by a group of former museum senior staff members. In a letter to the Times this month, they claim that the move is a sign that “the Natural History Museum is leading the museum world in its loss of expertise and breaking up of collections”.

The group, which includes former researchers, curators and heads of departments, argue that only natural history museums, with their vast collections and their expert curators working in intact institutions, can provide leadership in the study and understanding of the evolution of life on Earth. Creating virtual images of the collection will discourage people from actually handing specimens, they argue.

For its part, museum management said it expected the work on the new centre would begin next year and end in 2027. Moving its specimens would take a further three or four years.

At the British Museum, this transfer has already begun and several million of its cultural treasures are now being transferred to its archaeological research collection at the science park. This centre will house “the majority of the museum’s ancient world collections, including archaeological assemblages, sculptures, mosaics and historic cast collections,” said a spokesperson. Nearly 1.5m objects have already been moved, he added.

Unlike Kew and the NHM, there has been little opposition, however.