Naim Frashëri

Naim Frashëri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 May 1846 Frashër, Yanina Vilayet, Ottoman Empire (modern Albania) |

| Died | 20 October 1900 (aged 54) Kadıköy, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire (modern Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Occupation | Educator Historian

Journalist Poet Politician rilindas translator writer |

| Language | |

| Alma mater | Zosimaia School |

| Genre | Romanticism |

| Literary movement | Albanian Renaissance |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Naim bey Frashëri,[1][2] more commonly Naim Frashëri (/ˈnaɪm frɑːʃərɪ/; pronounced [naˈim fɾaˈʃəˈɾi]; 25 May 1846 – 20 October 1900), was an Albanian historian, journalist, poet, rilindas and translator who was proclaimed as the national poet of Albania. He is regarded as a pioneer of modern Albanian literature and one of the most influential Albanian cultural icons of the 19th century.[3]

Frashëri's works explored themes such as freedom, humanity, unity, tolerance and revolution. His twenty two works consist of fifteen works written in Albanian as well as four in Turkish, two in Greek and one in Persian. He is considered to be the most representative writer of Sufi poetry in Albanian, and having been under the influence of his uncle Dalip Frashëri, he tried to mingle Sufism with Western philosophy in his poetical ideals.[4][5] He had an extraordinarily profound impact on Albanian literature and society during the 20th century, most notably on Asdreni, Gjergj Fishta and Lasgush Poradeci, among many others.[6][7]

Ti Shqipëri, më jep nder, më jep emrin Shqipëtar ("You Albania, you give me honour, you give me the name Albanian"), a memorable line in his poem O malet e Shqipërisë, has been designated as the national motto of Albania. It speaks to unity, freedom and it embodies in its words a sense of pride towards the country and people.

Life[edit]

Family[edit]

Naim Frashëri was born on 25 May 1846[8] into a wealthy Albanian family of religious belief affiliated with the Bektashi tariqa of Islam, in the village of Frashër in what was then part of the Ottoman Empire and now Albania. He, Abdyl and Sami were one of eight children of Halid Frashëri (1797–1859), a landowner and military commander and Emine (1814–1861).[9] Halid belonged to the Dakollari branch of the Frashëri family. They were descendants of Ajaz Bey from Gramsh who in 1650–60 was given the command of Frashër. Ajaz Bey's grandfather, Hamza Bey had lost his lands in Tomorrica in 1570 when he rebelled and was exiled but the family's fortunes changed with the rise of Köprülü Mehmed Pasha who intervened on their behalf and they were pardoned.[10] Emine came from the family of Iljaz Bej Mirahori from the region around Korçë that traced its ancestry back to the 15th century.[11]

Naim and his brothers Abdyl and Sami were born and raised in the village of Frashër at the southern slopes of the Tomorr Mountains. He became acquainted with numerous cultures and languages such as Arabic, Ancient and Modern Greek, French, Italian, Ottoman Turkish and Persian.[12] He was one of the few men to whom the literary culture of the Occident and Orient was equally familiar and valuable.[11]

Upon the death of his father, he and his family settled to Ioannina where he earned initial inspiration for his future poetries written in the lyric and romantic style. After he suffered a severe lung infection, due to his congenital tuberculosis, in Constantinople, he joined his brother Abdyl in the fight for national freedom and consciousness of the Albanian people during the Albanian Renaissance in which he later became the most distinguished representative of that period.[11]

Education[edit]

His religion paved the way for much of his future accomplishments.

In the Tekke of Frashër, he received lessons in all the common subjects of his time especially in languages such as Arabic, Ottoman Turkish and Persian. As a member of a family which gave him a strong Bektashi upbringing, he spent a part of his time in a Bektashi tekke. After the death of their parents, the family moved to Ioannina in 1865. The eldest brother, Abdyl (b. 1839), became the family head at the age of 22 and started working as a merchant. That year Naim and Sami enrolled in the Zosimaia secondary school.[13] The education there provided Naim with the basics of a classical education along Western lines.[9] Apart from languages he learned in the Zosiamaia (Ancient and Modern Greek, French and Italian), Naim took private lessons in Persian, Turkish and Arabic from two important local Bektashi.[14]

After he finished his studies in 1870, Frashëri worked for a few months at the press office in Istanbul (1870) but was forced to return to his home village because of tuberculosis. The climate of Frashër helped Naim and soon he started work in the Ottoman bureaucracy as a clerk in Berat and later in Saranda (1872–1877).[15][16] However, in 1876 Frashëri left the job and went to Baden, in modern Austria to cure his problems with rheumatism in a health resort.[11][14]

Politics[edit]

In 1879, along with his brother Sami and 25 other Albanians, Naim Frashëri founded and was a member of the Society for the Publication of Albanian Writings in Istanbul that promoted Albanian language publications.[17][18] Ottoman authorities forbid writing in Albanian in 1885 that resulted in publications being published abroad and Frashëri used his initials N.H.F. to bypass those restrictions for his works. Later on, Albanian schools were established in 1887 in Southeastern Albania.[19]

An Albanian magazine, Drita, appeared in 1884 under the editorship of Petro Poga and later Pandeli Sotiri with Naim Frashëri being a behind the scenes editor as it was not allowed by Ottoman authorities to write in Albanian at that time.[20][21] Naim Frashëri and other Albanian writers like his brother Sami Frashëri would write using pseudonyms in Poga's publication.[20][21] Due to a lack of education material Naim Frashëri, his brother Sami and several other Albanians wrote textbooks in the Albanian language during the late 1880s for the Albanian school in Korçë.[21] In a letter to Faik Konitza in 1887, Frashëri expressed sentiments regarding the precarious state of the Ottoman Empire that the best outcome for Albanians was a future annexation of all of Albania by Austria-Hungary.[22]

In 1900 Naim Frashëri died in Istanbul. During the 1950s the Turkish government allowed for his remains to be sent and reburied in Albania.[23]

Career[edit]

Works[edit]

"Oh mountains of Albania

and you, oh trees so lofty,

Broad plains with all your flowers,

day and night I contemplate you,

You highlands so exquisite,

and you streams and rivers sparkling,

Oh peaks and promontories,

and you slopes, cliffs, verdant forests,

Of the herds and flocks

I'll sing out which you hold

and which you nourish.

Oh you blessed, sacred places,

you inspire and delight me!

You, Albania, give me honour,

and you name me as Albanian,

And my heart you have replenished

both with ardour and desire.

Albania! Oh my mother!

Though in exile I am longing,

My heart has ne'er forgotten

all the love you've given to me ..."

—Oh mountains of Albania

from Bagëti e Bujqësi[24]

With its literary stature and the broad range both stylistic and thematic of its content, Frashëri significantly contributed to the development of the modern Albanian literary language. The importance of his works lies less in his creative expression than in the social and political intention of his poetry and faith. His works were noted by the desire to the emergence of an independent Albanian unity that overcomes denominational and territorial differences, and by an optimistic belief in civilization and the political, economic and cultural rise of the Albanian people.

In his poem Bagëti e Bujqësi, Frashëri idyllically describes the natural and cultural beauty of Albania and the modest life of its people where nothing infringes on mystical euphoria and all conflicts find reconciliation and fascination.[25]

Frashëri saw his liberal religion as a profound source for Albanian libration, tolerance and national awareness among his religiously divided people.[26] He, therefore, composed his theological Fletore e Bektashinjet which is now a piece of national importance.[27] It contains an introductory profession of his faith and ten spiritual poems granting a contemporary perspective into the beliefs of the sect.[27]

- Kavâid-i farisiyye dar tarz-i nevîn (Grammar of the Persian language according to the new method), Istanbul, 1871.

- Ihtiraat ve kessfiyyat (Inventions and Discoveries), Istanbul, 1881.

- Fusuli erbea (Four Seasons), Istanbul, 1884.

- Tahayyülat (Dreams), Istanbul, 1884.

- Bagëti e Bujqësi (Herds and Crops), Bucharest, 1886.

- E këndimit çunavet (Reader for Boys), Bucharest, 1886.

- Istori e përgjithshme për mësonjëtoret të para (General history for the first grades), Bucharest, 1886.

- Vjersha për mësonjëtoret të para (Poetry for the first grades), Bucharest, 1886.

- Dituritë për mësonjëtoret të para (General knowledge for the first grades), Bucharest, 1886.

- O alithis pothos ton Skypetaron (The True Desire of Albanians, Greek: Ο αληθής πόθος των Σκιπετάρων), Bucharest, 1886.

- Luletë e Verësë (Flowers of the Summer), Bucharest, 1890.

- Mësime (Lessons), Bucharest, 1894.

- Parajsa dhe fjala fluturake (Paradise and the Flying Word), Bucharest, 1894.

- Gjithësia (Omneity), Bucharest, 1895.

- Fletore e bektashinjët (The Bektashi Notebook), Bucharest, 1895.

- O eros (Love, Greek: Ο Έρως), Istanbul, 1895.

- Iliadh' e Omirit, (Homer's Iliad), Bucharest, 1896.

- Histori e Skënderbeut (History of Skanderbeg), Bucharest, 1898.

- Qerbelaja (Qerbela), Bucharest, 1898.

- Istori e Shqipërisë (History of Albania), Sofia, 1899.

- Shqipëria (Albania), Sofia, 1902.

Legacy[edit]

The prime representative of Romanticism in Albanian literature, Frashëri is considered by many to be the most distinguished Albanian poet of the Albanian Renaissance whose poetry continued to have a tremendous influence on the literature and society of the Albanian people in the 20th century.[28][29] He is also widely regarded as the national poet of Albania and is celebrated as such among the Albanian people in Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and other Albanian-inhabited lands in the Balkans.

After his death, Frashëri became a great source of inspiration and a guiding light for the Albanian writers and intellectuals of the 20th century amongst them Asdreni, Gjergj Fishta, Mitrush Kuteli and Lasgush Poradeci.[6][7] His great work such as Bagëti e Bujqësi, Gjuha Jonë and Feja promoted national unity, consciousness, and tolerance in the breasts of his countrymen an enthusiasm for the culture and history of their ancestors.

Albanians of the Bektashi faith were in particular influenced and motivated by his work.[30] Himself a Bektashi, he desired purity of the Albanian language and had attempted in his lifetime to Albanianise hierarchical terms of the order in his work Fletore e Bektashinjët which called for an Albanian Bektashism.[31] His poem Bagëti e Bujqësi celebrated the natural beauty of Albania and the simple life of Albanian people while expressing gratitude that Albania had bestowed upon him "the name Albanian".[29] In Istori' e Skënderbeut, he celebrated his love for Albania by referring to the medieval battles between the Albanians and Ottomans while highlighting Skenderbeg's Albanian origins and his successful fight for liberation.[32][29] In Gjuha Jonë, he called for fellow Albanians to honour their nation and write in Albanian while in another poem Feja, he pleaded with Albanians not make religious distinctions among themselves as they all were of one origin that speak Albanian.[29]

Numerous organizations, monuments, schools, and streets had been founded and dedicated to his memory throughout Albania, Kosovo as well as to a lesser extent in North Macedonia and Romania. His family's house, where he was born and raised, in Frashër of Gjirokastër County is today a museum and was declared a monument of important cultural heritage.[33] It houses numerous artefacts including handwritten manuscripts, portraits, clothing and the busts of him and his brothers Abdyl and Sami.[34]

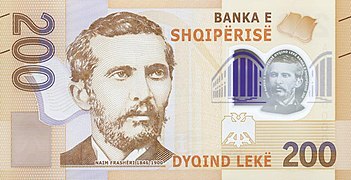

Frashëri's portrait is depicted on the obverses of the 500 lekë banknote from 1992 to 1996 and since 1996 on the 200 lekë banknote.[35][36] On the reverse side of the bill is a picture of his family house in Frashër. The Albanian nation has established an order of merit that bears his name which was awarded to, amongst others, the Albanian nun and missionary Mother Teresa.[37]

Gallery[edit]

-

Frashëri (up right) on the reverse of a 1964 10 Lekë banknote

-

Frashëri on the obverse of a 1994 500 Lekë banknote

-

Frashëri on the obverse of a 2012 200 Lekë banknote

-

Frashëri on the obverse of 2017 200 Lekë polymer banknote

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2013). "FRASHËRI, NAIM Bey". A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History. I.B.Tauris. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-78076-431-3.

- ^ Balazs Trencsenyi; Michal Kopecek, eds. (2006). "Sami Frashëri: Albania, what it was, what it is, and what it will be?". National Romanticism: The Formation of National Movements: Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe 1770–1945. Vol. 2. Central European University Press. p. 297. ISBN 9789637326608.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2004). "The Hybrid Soil of the Balkans: A Topography of Albanian Literature". History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Vol. 2. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 291. ISBN 9789027234537.

- ^ Osmani, Edlira. "God in the Eagles' Country: The Bektashi Order" (PDF). iemed.org. Quaderns de la Mediterrània 17, 2012. p. 113. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ H.T.Norris (1993), Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society Between Europe and the Arab World, Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press, p. 76, ISBN 978-0-87249-977-5, OCLC 28067651

- ^ a b Robert Elsie (29 July 2005). Albanian Literature: A Short History. I.B.Tauris, 2005. pp. 100–103. ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4.

- ^ a b Robert Elsie (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Rowman & Littlefield, 2010. pp. 362–363. ISBN 978-0-8108-6188-6.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-6188-6.

- ^ a b Gawrych 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Frashëri 2014, p. 385.

- ^ a b c d Elsie, Robert (2005). Albanian Literature: A Short History. I.B.Tauris. pp. 67–70. ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4.

- ^ Robert Elsie. "Die Drei Frashëri-Brüder" (PDF). elsie.de (in German). p. 23.

Hier lernte er Alt- und Neugriechisch, Französisch und Italienisch. Sein besonderes Interesse galt dem Bektaschitum, den Dichtern der persischen Klassik und dem Zeitalter der französischen Aufklärung. Mit dieser Erziehung verkörperte er den osmanischen Intellektuellen, der in beiden Kulturen, der morgenländischen und der abendländischen, gleichermaßen zu Hause war.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 13, 26.

- ^ a b Qosja, Rexhep (2000). Porosia e madhe: monografi mbi krijimtarinë e Naim Frashërit [The Great Instruction]. Botime Toena. pp. 34–42. ISBN 9789992713372.

- ^ Dhimitër S. Shuteriqi (1971). Historia e letërsisë shqipe (History of Albanian Literature).

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 119.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 128.

- ^ a b Skendi 1967, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Gawrych 2006, p. 88.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 268.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 200.

- ^ Robert Elsie (29 July 2005). Albanian Literature: A Short History. I.B.Tauris, 2005. p. 72. ISBN 9781845110314.

- ^ Arshi Pipa (2013). Letërsia Shqipe: Perspektiva Shoqërore Volume 3 of Trilogjia Albanika (in Albanian). Princi. pp. 97–100. ISBN 9789928409096.

- ^ Albert DOJA (2013). "The politics of religious dualism: Naim Frashëri and his elective affinity to religion in the course of 19th-century Albanian activism" (PDF). Social Compass. 60: 3. doi:10.1177/0037768612471770. S2CID 15564654. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2019.

- ^ a b Robert Elsie (25 July 2019). The Albanian Bektashi: History and Culture of a Dervish Order in the Balkans. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019. pp. 30–36. ISBN 9781788315715.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2005), "Writing in the independence period", Albanian literature: a short history, London, UK: I.B. Tauris in association with the Centre for Albanian Studies, p. 100, ISBN 1-84511-031-5, retrieved 18 January 2011,

major source of inspiration and guiding lights for most Albanian poets and intellectuals

- ^ a b c d Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 9781400847761.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 166.

- ^ Skendi 1967, pp. 123, 339.

- ^ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 9781845112875.

- ^ "RRETHI I PËRMETIT" (PDF). imk.gov.al (in Albanian). Instituti i Monumenteve të Kulturës. p. 2.

- ^ "DREJTORIA E PËRGJITHSHME EKONOMIKE DHE SHËRBIMEVE MBËSHTETËSE DREJTORIA E BUXHETIT DHE MENAXHIMIT FINANCIAR—RAPORTET E MONITORIMIT 12–MUJORI VITI 2018" (PDF). kultura.gov.al (in Albanian). Ministry of Culture of Albania. pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Currency: Banknotes in circulation". bankofalbania.org. Tirana: Banka e Shqipërisë. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009.

- ^ "200 Lek". bankofalbania.org. Tirana: Banka e Shqipërisë.

- ^ Parliament of Albania. "Ligj Nr.6133, datë 12.2.1980 Për titujt e nderit dhe dekoratat e Republikës Popullore Socialiste të Shqipërisë" (in Albanian). Parliament of Albania. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

Sources[edit]

- Frashëri, Alfred; Frashëri, Neki (2014). Frashëri në historinë e Shqipërisë. Dudaj. ISBN 978-99943-0-051-8.

- 1846 births

- 1900 deaths

- 19th-century Albanian poets

- 19th-century Albanian writers

- Albanian Sufis

- Activists of the Albanian National Awakening

- Muslim poets

- Politicians from the Ottoman Empire

- Romantic poets

- Zosimaia School alumni

- People from Gjirokastër County

- Bektashi Order

- Sufi poets

- Civil servants from the Ottoman Empire

- Albanian people from the Ottoman Empire

- Albanian-language poets

- Albanian male poets

- 19th-century Albanian historians

- Albanian translators

- 19th-century historians from the Ottoman Empire

- Modern Greek-language writers

- Turkish-language writers

- 19th-century translators

- French–Albanian translators

- Persian–Albanian translators

- 19th-century male writers

- Dulellari family

- Frashëri family

- Albanian Arabic-language poets

- Arabic-language poets from the Ottoman Empire

- Translators of the Quran into Albanian

- Albanian Persian-language writers