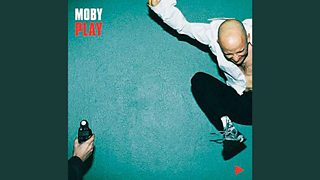

Behind Moby’s Play – one of music’s most unlikely success stories

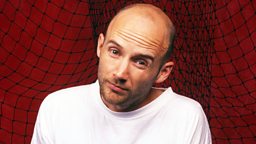

Moby joins Radio 2 to celebrate his hugely successful album Play in a new two-part series.

Recorded and released at the end of the 20th Century, it has gone on to become one of the 21st Century's most iconic and influential records.

-

![]()

Listen now to Moby: 20 years of Play

Moby lifts the lid on making the record, how he found the samples he used, and why it struck such a chord globally.

Play was recorded by a musician who believed his career was dead in the water. It consisted of many tracks he would have preferred to omit, and Moby firmly believed it would be his final album. In his own words: “When I was making it, I didn’t think anyone was gonna listen to it.”

Released on 17 May 1999 to little fanfare or acclaim, the album would somehow eventually make for one of music’s most unlikely success stories, leading to over 9 million worldwide sales.

Cut to 2019, and Moby has since released 11 more albums post-Play, been nominated for six Grammy Awards, headlined Glastonbury in 2003, and had Adele citing his breakthrough record as a huge influence on her 25 album.

This is the story of how Play made Moby an unexpected superstar:

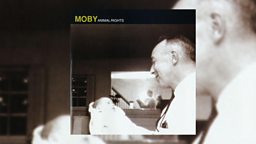

His previous album was a “complete and abject failure”

1996’s Animal Rights saw Moby embracing his hardcore punk roots, but it was a stylistic shift that fans of his early 90s electronica didn’t warm to. It peaked at Number 38 in the UK Official Albums Chart, and its maker would later call it “a complete and abject failure.”

Critics weren’t kind either. Spin Magazine’s James Hunter called the record “odd and bewildering and off and frustrating”.

At this point in his career, Moby was also experiencing personal trauma when his mum passed away with lung cancer. “My North American record company Elektra had dropped me. My career was falling apart. I was battling panic attacks. I was drinking too much. And that’s when I started working on Play. Oddly enough, Play is not a morbid record.”

So Moby saw the follow-up album as his last roll of the dice: "The only criteria for figuring out what songs were gonna be included, was… I thought to myself, ‘This is gonna be my last album, so if I get the sequence right, it increases the chances that one or two people might listen to the entire album.'"

Play was recorded on a tiny budget

Without major label support or funding, Moby was left to his own devices, and he recorded Play “on second-hand equipment” in his bedroom. At a time when expertly-produced, shiny pop songs made by the likes of Britney Spears and *NSYNC were topping charts, the idea of a do-it-yourself electronic album achieving the same looked inconceivable.

Moby wanted a vocal-led record, but he couldn’t sing well enough, so he relied on samples lifted from CDs gifted by his friends Dimitri and Gregor Ehrlich.

The only exception was Porcelain, which Moby contributes the vocals for. “I grew up listening to a lot of post-punk, which was not about virtuoso vocal performances. I found that kind of empowering.”

A blissed-out centrepiece of Play and arguably the record’s most successful song, Porcelain found fame after soundtracking the Danny Boyle-directed The Beach, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio. “It was [his] first movie after Titanic. People went to see it, and Porcelain was featured very prominently. Pete Tong was the music supervisor, so I guess Pete, Danny and Leo: I would like to say thank you very much.”

“When I first recorded it, I didn’t think it was very good,” says Moby. “This was one of many songs that I didn’t want to put on the album. I recorded it, I mixed it, it didn’t really have a chorus, and I was going to leave it off the album. At the time I had a few different managers – which is weird, because I barely had a career – and all three of them really liked Porcelain. So I kind of included it as a favour to them.”

Disclaimer: Third-party videos may contain adverts.

Out of nowhere, Play was everywhere

After he finished mixing the record, Moby pitched Play to labels including Warner Bros and RCA, getting nothing but rejection. And despite eventually finding a home on the Richard Branson-founded label V2, it entered at a lowly 33 in the UK Albums Chart. It only remained in the Top 100 for another couple of weeks, before dropping out completely for several months, and wasn’t until April 2000 when it finally climbed to No.1.

The reviews were stronger for Play than they were for Animal Rights, but it still wasn’t selling units. “First show that I did on the tour for Play was in the basement of the Virgin Megastore in Union Square,” he told Rolling Stone in 2009. “Literally playing music while people were waiting in line buying CDs. Maybe 40 people came.” Radio stations and MTV weren’t interested.

Disclaimer: Third-party videos may contain adverts.

There are sleeper successes and then there’s Play. Months after release, songs on the record gradually started appearing in adverts in North America. Porcelain soundtracked a liqueur advert. A credit card company featured Find My Baby. A car manufacturer used Run On to advertise their latest model. And a chocolate-maker found something comforting in Everloving.

Eventually, Play would be the first album ever to have all of its songs synced in films, television or commercials. As a result of this ubiquity, radio and TV heads who’d previously shunned Play’s songs started to take notice.

“The week Play was released, it sold worldwide around 6,000 copies. Eleven months after Play was released, it was selling 150,000 copies a week,” Moby told Rolling Stone.

Moby still can’t figure out how it all happened

Even today when speaking to Radio 2, Moby can’t claim to have anticipated any of the record’s success. “Maybe this is a bad thing to say, but I still don’t think the music on Play is better or worse than the other records I’ve made. Obviously I’m mistaken. I don’t know why any of these songs connected with people,” he admits.

“If I had to possibly [guess], it’s because there’s a vulnerable, emotional quality to a lot of the music. And it was released at a time when there was not a lot of vulnerable emotion in music… I made this record in my bedroom, with broken equipment, after my mum died; so I think there was an inherent vulnerability in every aspect of the creation.”

Moby also believes he was fortunate in terms of when Play came out; a time he considers to be more carefree than the noughties. “Think about what the world was like in ’99 and 2000. We were innocent. The Soviet Union had ended. Bill Clinton was President. Tony Blair was Prime Minister and hadn’t disgraced himself by being a friend of George Bush yet. 9/11 hadn’t happened. Social media hadn’t happened. The world felt benign and innocent. When someone hears the music from Play, or other albums from that period, it’s their own youth and innocence.”

Play’s mellow, oddly uplifting electronic sound spoke to casual listeners and dance-obsessives too. “Along comes me and Air and Portishead and Massive Attack. It’s still dance-inspired electronic music. There wasn’t a cabal of electronic musicians who decided to make music you could play at a dinner party. But unintentionally that’s what we all ended up doing.”

The whirlwind success of Play was “great, until it came really close to killing me,” Moby says. “That’s not hyperbole. But boy, those first couple of years… It was an endless, escalating party. And I could be disingenuous and say it wasn’t fun, but it was really fun.”