Approach Considerations

Antibiotic selection, route of administration, and duration of therapy for Lyme disease are guided by the patient’s clinical manifestations and stage of disease, as well as the presence of any concomitant medical conditions or allergies. Prompt treatment increases the likelihood of therapeutic success. With prompt and appropriate antibiotic treatment, most patients with early-stage Lyme disease recover rapidly and completely.

A guideline from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommends administering a single dose of oral doxycycline for prophylaxis within 72 hours of removing a tick after a high-risk bite. For a bite to be considered high risk, it must be from an Ixodes tick, in a highly endemic area, and from a tick engorged and attached for 36 hours or more. The dose is 200 mg for adults and 4.4 mg/kg, up to a maximum of 200 mg, for children. Antibiotic prophylaxis should not be given for tick bites that are equivocal or low risk [6]

Doxycycline has traditionally been considered contraindicated in patients younger than 8 years and in pregnant and breastfeeding women. Although more recent research suggests that doxycycline for at least up to 14 days is safe in young children, amoxicillin remains the usual first choice for pediatric patients. [6] See the tables below.

Table 1. Clinical presentation and therapy for the stages of Lyme disease (Open Table in a new window)

Clinical Manifestations |

Adult Dose |

Pediatric Dose |

Erythema migrans |

Doxycycline 100 mg PO BID for 10-14 days, OR

Amoxicillin 500 mg PO TID for 14 days, OR

Cefuroxime axetil 500 mg PO BID for 14 days

Patients unable to take doxycycline or beta-lactam antibiotics: Azithromycin 500 mg PO qDay for 7 days |

Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 2 doses; not to exceed 100 mg/dose for 10-14 days, OR

Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 3 doses; not to exceed 500 mg/dose for 14 days, OR

Cefuroxime axetil 30 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 2 doses; not to exceed 500 mg/dose for 14 day |

Facial palsy [3] |

Doxycycline 100 mg PO BID for 14-21 days |

Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 2 doses; not to exceed 100 mg/dose for 14-21 days |

Lyme meningitis or radiculoneuritis [3] |

Doxycycline 200 mg/day PO, divided into 1-2 doses for 14-21 days, OR

Ceftriaxone 2 g IV qDay for 14-21 days; may substitute for oral therapy once the patient is stabilized or discharged to complete the course |

Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 1-2 doses; not to exceed 100 mg/dose for 14-21 days, OR

Ceftriaxone 50-75 mg/kg IV qDay; not to exceed 2 g/day for 14-21 days; may substitute for oral therapy once the patient is stabilized or discharged to complete the course |

Lyme disease–associated meningitis, cranial neuropathy, radiculoneuropathy, or with other peripheral nervous system (PNS) manifestations |

Without parenchymal involvement of brain or spinal cord: IV ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, penicillin G, or oral doxycycline With parenchymal involvement of brain or spinal cord: IV antibiotics are preferred |

|

Mild lyme carditis (1st degree AV block with PR interval < 300 milliseconds) [3] |

Doxycycline 100 mg PO BID for 14-21 days, OR

Amoxicillin 500 mg PO TID for 14-21 days, OR Cefuroxime axetil 500 mg PO BID for 14-21 days |

Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 2 doses; not to exceed 100 mg/dose for 14-21 days, OR

Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 3 doses; not to exceed 500 mg/dose for 14-21 days, OR

Cefuroxime axetil 30 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 2 doses; not to exceed 500 mg/dose for 14-21 days |

Severe lyme carditis (symptomatic, 1st degree AV block with PR interval ≥300 milliseconds, 2nd or 3rd degree AV block) [3] |

Ceftriaxone 2 g IV qDay for 14-21 days; once symptoms and high-grade AV block resolve, consider transitioning to oral antibiotics to complete treatment course |

Ceftriaxone 50-75 mg IV qDay; not to exceed 2 g/day for 14-21 days; once symptoms and high-grade AV block resolve, consider transitioning to oral antibiotics to complete treatment course |

Borrelial lymphocytoma |

Oral antibiotic therapy for 14 days |

|

Arthritis |

Doxycycline 100 mg PO BID for 28 days, OR

Amoxicillin 500 mg PO TID for 28 days, OR

Cefuroxime axetil 500 mg PO BID for 28 days |

For ≥8 years:

Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 2 doses; not to exceed 100 mg/dose for 28 days, OR

Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 3 doses; not to exceed 500 mg/dose for 28 days, OR

Cefuroxime axetil 30 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 2 doses; not to exceed 500 mg/dose for 28 days

For < 8 years:

Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 3 doses; not to exceed 500 mg/dose for 28 days, OR

Cefuroxime axetil 30 mg/kg/day PO, divided into 2 doses; not to exceed 500 mg/dose for 28 days |

Arthritis without any response to initial treatment |

Ceftriaxone 2 g IV qDay for 14-28 days |

Ceftriaxone 50-75 mg IV qDay; not to exceed 2 g/day for 14-28 days |

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans |

Oral antibiotic therapy 21-28 days |

|

Table 2. Adult and pediatric treatment options, dosages, and routes of administration (Open Table in a new window)

|

Treatment |

Adult Dose |

Pediatric Dose |

Oral Therapy |

Doxycycline (patients > 8 y) |

100 mg twice a day |

Doxycycline 4.4 mg/kg/day PO (up to 100 mg BID) |

Amoxicillin |

500 mg three times a day |

50 mg/kg/day (up to 500 mg) in 3 divided doses |

|

Cefuroxime axetil |

500 mg twice a day |

30 mg/kg/day (up to 500 mg) in 2 divided doses |

|

Phenoxymethylpenicillin |

500 mg four times a day, or 1 gm three times a day |

50-100 mg/kg/day in three divided doses; maximum 1 g/dose |

|

Azithromycin (for patients unable to take doxycycline or beta-lactams) |

500 mg once a day

|

50-100 mg/kg/day in three divided doses; maximum 1 g/dose |

|

Intravenous therapy |

Ceftriaxone |

2 g once a day |

10 mg/kg/day (maximum, 500 mg/day) |

Cefotaxime |

2 g every 8 h |

150-200 mg/kg (up to 2 g) every 8 h |

|

Penicillin G |

18-24 million U/d divided every 4 h |

200,000-400,000 mg/kg (up to 2 g) every 8 h |

In most patients with carditis, prompt institution of appropriate antibiotics is the only treatment needed. However, occasional patients with Lyme disease–related atrioventricular (AV) block may require hospitalization for temporary cardiac pacing. The indications for cardiac pacing are the same as for any other patient with varying degrees of heart block. Permanent pacing is very rarely needed.

Symptoms of arthritis may persist for a few weeks beyond adequate therapy. Repeat treatment usually is not necessary unless symptoms worsen or persist beyond 2 months.

Persistent arthritis after clearance of the infection is most likely related to autoimmunity and is more prevalent among individuals with HLA-DR2, HLA-DR3, or HLA-DR4 allotypes. These patients should be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), plus hydroxychloroquine if necessary. As a last resort, such patients may need a synovectomy to eradicate the inflammatory arthritis in the involved joint.

Neurologic manifestations of Lyme disease in both adults and children respond well to penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, and doxycycline. Although most studies of neuroborreliosis have used intravenous antibiotics, European studies support use of oral doxycycline in adults with meningitis, cranial neuritis, or radiculitis, with intravenous regimens reserved for patients with parenchymal central nervous system (CNS) involvement, other severe neurologic symptomatology, or failure to respond to oral treatment. [57]

Borrelial lymphocytoma is sufficiently uncommon that no comparative trials address the ideal duration of treatment, route of administration of the antibiotic, or the choice of medication. Treatment is usually with 14-21 days of oral antibiotics. When symptoms of dissemination are noted, however, parenteral therapy sometimes is used.

Physicians should observe patients closely for possible Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions after the institution of therapy. This allergic/inflammatory response may manifest in the skin, mucous membranes, viscera, or nervous system.

In endemic areas, antibiotic prophylaxis may be appropriate for selected patients with a recognized tick bite (see Prevention). Prophylactic antibiotics are not routinely recommended, however, as tick bites rarely result in Lyme disease, and if infection does develop, early antibiotic treatment has excellent efficacy.

Several groups have published Lyme disease guidelines. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has released clinical practice guidelines for the assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease. [53] The American Academy of Neurology has established guidelines for the treatment of nervous system Lyme disease. [57]

The International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS) issued updated recommendations for the management of Lyme disease in 2014. [62] The recommendations are all based on "very low quality evidence" and use patient preference as major portion of the support for the recommendations. In addition, the recommendations are limited to three specific aspects of Lyme disease. The differences between the IDSA and ILADS recommendations are outlined in the table below.

Table 3. Comparison of Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS) recommendations for Lyme disease treatment (Open Table in a new window)

Treatment Focus |

IDSA |

ILADS |

Treatment of a tick bite without symptoms of Lyme disease |

Doxycycline, 200 mg as a single dose |

Doxycycline, 100 mg bid for 20 days |

Erythema migrans |

Doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime for 14-21 days |

Doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime for 28-42 days or azithromycin for at least 21 days |

“Persisting symptoms of Lyme disease” |

No antibiotic therapy |

Multiple agents (individually or in combination) are mentioned without specific doses or duration recommended |

Controversy regarding the treatment of Lyme disease abounds, including an antitrust investigation initiated in 2008 by the Connecticut Attorney General (CAG) into the development process for the 2006 IDSA Lyme disease treatment guidelines. The CAG claimed the process was tainted by suppression of scientific evidence and conflicts of interest. [63]

In April 2008, the CAG and the IDSA reached an agreement to end the investigation. In 2010, a review panel convened as part of that agreement concluded that “the IDSA’s 2006 Lyme disease guidelines were based on the highest-quality medical and scientific evidence available at the time and are supported by evidence that has been published in more recent years.” [64]

Treatment of Early Lyme Disease

Early localized Lyme disease refers to isolated erythema migrans and to an undifferentiated febrile illness. This stage occurs 1-30 days after the tick bite. In endemic areas, patients with erythema migrans and a recent history of possible or proven tick exposure can be treated empirically, without laboratory confirmation of the diagnosis. Serologic testing is appropriate for patients who present more than 3 weeks after tick exposure.

Doxycycline, amoxicillin, cefuroxime axetil, or phenoxymethylpenicillin is recommended for the treatment of adult patients with early localized or early disseminated Lyme disease associated with erythema migrans, in the absence of specific neurologic manifestations or third-degree heart block. Antibiotics recommended for children include amoxicillin, cefuroxime axetil, and phenoxymethylpenicillin; in children 8 years and older, doxycycline may be used. Because of its cost, cefuroxime axetil is reserved for patients unable to take amoxicillin or doxycycline

Treatment for 10 to 14 days is recommended (10 d for doxycycline and 14 d for amoxicillin, cefuroxime axetil, or phenoxymethylpenicillin). [6] Longer treatment was previously recommended. [65, 66] Erythema migrans typically shows improvement within a few days after the institution of appropriate antibiotic therapy.

The macrolide antibiotic azithromycin is an alternative agent that can be used when the first-line agents are not tolerated or are contraindicated. Although one study found amoxicillin significantly superior to azithromycin for patients with erythema migrans, other studies have found that azithromycin has clinical efficacy comparable to that of other antimicrobials. [6, 67] Treatment duration is 5–10 days, with a 7-day course preferred in the United States. [6]

Neurologic Lyme disease is effectively treated with a 2-week course of parenteral penicillin, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime. [57, 68] Oral doxycycline is as efficacious as parenteral antibiotics in patients who have Lyme-associated meningitis, facial nerve palsy, or radiculitis. [57]

Pregnancy

For pregnant women with erythema migrans, some physicians recommend parenteral therapy, although data on this are limited. Isolated reports exist of transplacental transmission from the mother to fetus. One European descriptive study showed good results of parenteral ceftriaxone in pregnant women with erythema migrans. [69]

Pregnant women who develop Lyme disease should not be treated with doxycycline or another tetracycline. Risks to the fetus include permanent discoloration of the teeth, enamel hypoplasia, and retardation of skeletal development.

Lyme Arthritis

In patients without neurologic disease, Lyme arthritis can usually be treated successfully with oral antibiotics, with an extended treatment time of 28 days. Recommended regimens for adult patients are as follows [53] :

-

Doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily

-

Amoxicillin, 500 mg three times daily

-

Cefuroxime axetil, 500 mg twice daily per day

Recommended regimens for pediatric patients are as follows [53] :

-

Amoxicillin, 50 mg/kg/day in three divided doses (maximum of 500 mg/dose)

-

Cefuroxime axetil, 30 mg/kg/day in two divided doses (maximum of 500 mg/dose)

-

Doxycycline, 4.4 mg/kg/day in two divided doses (maximum of 100 mg/dose), if aged ≥8 years

Patients with mild residual joint swelling after a recommended course of oral antibiotic therapy can be re-treated with another 4-week course of oral antibiotics. Patients whose arthritis fails to improve or worsens can be re-treated with a 2- to 4-week course of intravenous ceftriaxone. IDSA guidelines suggest that clinicians consider waiting several months before starting a second round of antibiotics, as joint inflammation tends to resolve slowly even when the infection has been eliminated. [53]

In patients with persistent arthritis despite intravenous therapy, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of synovial fluid (and synovial tissue, if available) can be done. PCR results may remain positive for several weeks after the eradication of Borrelia burgdorferi; nevertheless, if PCR is positive for B burgdorferi DNA, the patient can be treated with oral antibiotic therapy for another month. [27]

If PCR is negative, the patient should be given symptomatic treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs NSAIDs). If necessary, NSAID treatment can be supplemented with oral hydroxychloroquine, 20 mg twice daily. [27, 53] Consultation with a rheumatologist is recommended in these cases.

Eventual resolution of chronic Lyme arthritis can be expected in all patients. However, patients who continue to have significant pain or limitation of function after 3-6 months of symptomatic therapy can be considered for arthroscopic synovectomy. [27, 53]

Intra-articular corticosteroids should not be given before antibiotic treatment, as they may promote persistent Lyme arthritis. Intra-articular corticosteroids are rarely indicated after antibiotic treatment. [68]

Lyme Carditis

The patient with myocarditis generally is not very ill, and significant muscle dysfunction is unusual. Pericarditis with tamponade, while rare, has been reported.

Patients with atrioventricular (AV) heart block and/or myopericarditis associated with early Lyme disease may be treated with either oral or parenteral antibiotic therapy for 14 days (range, 14-21 days). Hospitalization and continuous monitoring are advisable for patients with any of the following [70] :

-

Associated symptoms (eg, syncope, dyspnea, or chest pain)

-

Second-degree or third-degree AV block

-

First-degree heart block with prolongation of the PR interval to more than 300 milliseconds (the degree of block may fluctuate and worsen very rapidly in such patients)

For patients with advanced heart block, a temporary pacemaker may be required; consultation with a cardiologist is recommended. Use of the pacemaker may be discontinued when the advanced heart block has resolved. An oral antibiotic treatment regimen should be used for completion of therapy and for outpatients, as is used for patients with erythema migrans without carditis.

Neurologic Manifestations

Although facial palsies may resolve without treatment, oral antibiotic therapy may prevent further sequelae. Encephalitis/encephalopathy should be treated with intravenous antibiotic therapy for 28 days.

The use of ceftriaxone in early Lyme disease has been recommended for adult patients with acute meningitis or radiculopathy. Possible satisfactory alternatives include parenteral therapy with cefotaxime or penicillin G. For patients who are intolerant of β-lactam antibiotics, increasing evidence indicates that oral doxycycline (200-400 mg/d in two divided doses orally for 10-28 d) may be adequate. [71, 72, 73] For all patients, except those with encephalitis, oral agents may be satisfactory. [74] With any regimen, neurologic symptoms may take 6 months to reach maximum improvement.

Patients with Lyme meningitis may need to be admitted not only for pain control but also for administration of intravenous antibiotics. If diagnostic uncertainty exists regarding the etiology of the meningitis, the antibiotic coverage may need to be extended for other more serious bacterial pathogens until the precise etiology is clarified.

Adult patients with late neurologic disease affecting the central or peripheral nervous system should be treated with intravenous medication. Response to treatment is usually slow and may be incomplete. Retreatment is not recommended unless relapse is shown by reliable objective measures.

Ocular Manifestations

Conjunctivitis and photophobia in stage 1 Lyme disease require no therapy. Bell palsy in stage 2 Lyme disease is self-limited, but patients require supportive therapy to prevent the complications of exposure keratitis. Keratitis and episcleritis benefit from topical corticosteroids, usually a short course of prednisolone acetate 1% or fluorometholone 0.1%.

A treatment regimen for severe neuro-ophthalmic disease (involving the optic nerve) or posterior segment disease (eg, pars planitis, vitreitis) has not been established. Oral corticosteroids without concomitant antibiotics should not be used.

The best approach for these patients might be a trial of antibiotic therapy, in which patients receive 2-3 weeks of intravenous penicillin or ceftriaxone. If patients respond to treatment, the trial is successful, ocular Lyme disease is diagnosed, and no further therapy is needed. Recurrences of Lyme uveitis, once adequate intravenous therapy has been given, can be treated with judicious corticosteroids.

Acrodermatitis Chronica Atrophicans

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is usually treated with 1-month course of oral antibiotics, usually a beta-lactam or doxycycline. One study showed fewer relapses with 30 days compared with 20 or fewer days of therapy. In the same study, 30 days of oral antibiotics were more effective than 15 days of intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g/d). [75] It is important to ensure that no neurologic manifestations are present before embarking on oral therapy.

Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome

Despite appropriate antibiotic treatment, patients with Lyme disease may experience lingering symptoms similar to fibromyalgia (eg, fatigue, pain, joint and muscle aches). This condition has been termed chronic Lyme disease or, more precisely, post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS). [76]

These symptoms have not been shown in any controlled trials to be responsive to antibiotic therapy. [68] The IDSA/AAN/ACR guideline recommends against additional antibiotic therapy for patients who have persistent or recurrent nonspecific symptoms (eg, fatigue, pain, cognitive impairment) after treatment for appropriately diagnosed Lyme disease but who have no objective evidence of reinfection or treatment failure (eg, arthritis, meningitis, neuropathy). [6]

A study by Klempner et al failed to show a benefit of treatment with 2 g of intravenous ceftriaxone daily for 30 days, followed by oral doxycycline at 200 mg/d for 60 days. [77] Long-term IV ceftriaxone therapy can result in the formation of biliary sludge, which can lead to biliary colic.

Similarly, the Persistent Lyme Empiric Antibiotic Study Europe (PLEASE) study, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 280 patients, found that longer-term use of antibiotics does not improve health-related quality of life in patients with PTLDS. In PLEASE, patients received open-label ceftriaxone for 2 weeks and were then randomized to a 12-week oral regimen of doxycycline (n = 86), clarithromycin combined with hydroxychloroquine (n = 96), or placebo (n = 98). At the end of the treatment period, the three groups showed no significant difference in health-related quality of life, which was the study's primary outcome, or in secondary outcomes, including physical and mental aspects of health-related quality of life and fatigue. [78]

Extended antibiotic therapy, sometimes for longer than 6 months, has been advocated for PTLDS. This not only can cause great harm to patients but also has resulted in one or more deaths. [79] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported five cases of serious bacterial infections in patients receiving intravenous antibiotic treatment for chronic Lyme disease, including septic shock, osteomyelitis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and paraspinal abscess. [80]

The existence of PTLDS has been called into question as a result of a lack of direct evidence of persistent infection. [81, 82] Hassett and colleagues reported that rates of psychiatric comorbidity and other psychological factors (eg, depression, anxiety, tendency to catastrophize pain) were higher in patients with “chronic Lyme disease” (defined as symptomatic patients with previously treated Lyme disease and patients whose symptoms were attributed to Lyme disease without good evidence for Lyme disease) than in other patients commonly seen in Lyme disease referral centers, and that those factors were related to poor functional outcomes. [83]

The IDSA/AAN/ACR draft guideline notes that patients labeled as having chronic Lyme disease may in fact have other specific disorders that are diagnosable and potentially treatable, and in such cases, management should be directed accordingly. However, many of these patients have medically unexplained illness, and management of these symptoms complexes remains poorly understood. [84]

Jutras et al found evidence linking Lyme arthritis with a chemically atypical peptidoglycan (PGBb) that is a major component of the Borrelia burgdorferi cell envelope. B burgdorferi sheds fragments of PGBb into its environment during growth, and PGBb is released but not degraded when the spirochete dies. These researchers detected PGBb in 94% of synovial fluid samples (32 of 34) from patients with Lyme arthritis, many of whom had undergone oral and intravenous antibiotic treatment. Synovial fluid analysis demonstrated an ongoing immune response (ie, anti-PGBb immunoglobulins and proinflammatory cytokines, particularly tumor necrosis factor α). Systemic administration of PGBb in mice elicited acute arthritis. [85]

These researchers propose that persistence of this antigen in the joint may contribute to synovitis after antibiotics have eradicated B burgdorferi, by provoking a chronic innate and adaptive immune response. They speculate that this mechanism may expain other post-Lyme complications, such as skin lesions, carditis, and meningitis. [85]

Co-infection

Co-infection with other tick-borne illnesses occur in roughly 10-15% of patients with Lyme disease and should be considered in patients with a poor response to conventional antimicrobial therapy or atypical clinical presentations (eg, high fever, leukopenia). Co-transmitted infective organisms can include the following:

-

Babesia microti, the primary cause of babesiosis

-

Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Ehrlichia chaffeensis, which cause ehrlichiosis

-

Flavivirus, the cause of tick-borne encephalitis

-

Powassan or tick-borne encephalitis-like virus

IDSA/AAN/ACR guidelines include the following recommendations regarding co-infections [6] :

-

Assess for possible coinfection with A phagocytophilum and/or B microti in geographic regions where these infections are endemic, in patients who have a persistent fever for > 1 day while on antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease. If fever persists despite treatment with doxycycline, B microti infection is an important consideration.

-

On laboratory testing, characteristic abnormalities found in both anaplasmosis and babesiosis include thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, neutropenia, and/or anemia. Evidence of hemolysis, such as an elevated indirect bilirubin level, anemia, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase is particularly suggestive of babesiosis.

Prevention

Prevention of tick-borne disease can be divided into personal and environmental measures. Clinicians in endemic areas should provide patient education on personal measures for tick avoidance and management of tick exposure (see Patient Education).

Environmental prevention involves clearing underbrush and spraying acaricides in the spring around property sites. These measures prevent both mice and ticks from encroaching on properties. Studies involving the treatment of wild deer and mice have not been conclusive in reducing tick-borne diseases in humans.

Tick removal

In patients in endemic areas who present with an attached tick, prompt removal can reduce the likelihood of contracting Lyme disease. Transmission of infection is unlikely if the duration of tick attachment is less than 24 hours, but is very likely for ticks attached for longer than 72 hours.

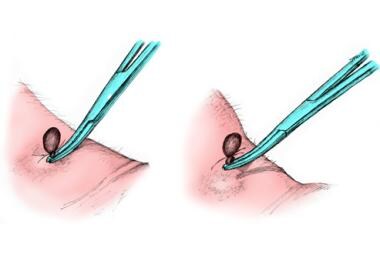

Removal of a tick is ideally accomplished using fine-tipped forceps and wearing gloves. Grasp the tick as close to the skin surface as possible, including the mouth parts, and pull upward with steady, even traction. (See the image below). Do not twist or jerk the tick because this may cause the mouth parts to break off and remain in the skin; however, note that the mouth parts themselves are not infectious. Wear gloves to avoid possible infection.

To remove a tick, use fine-tipped forceps and wear gloves. Grasp the tick as close to the skin surface as possible, including the mouth parts, and pull upward with steady, even traction. Do not twist or jerk the tick because this may cause the mouth parts to break off and remain in the skin; however, note that the mouth parts themselves are not infectious. When removing, wear gloves to avoid possible infection.

To remove a tick, use fine-tipped forceps and wear gloves. Grasp the tick as close to the skin surface as possible, including the mouth parts, and pull upward with steady, even traction. Do not twist or jerk the tick because this may cause the mouth parts to break off and remain in the skin; however, note that the mouth parts themselves are not infectious. When removing, wear gloves to avoid possible infection.

The use of forceps and gloves represents an optimal method of removal. However, removal of the tick should not be delayed in order to obtain forceps and it is extremely unlikely that one can become infected by touching an engorged tick even if the tick is carrying Borrelia (which most of them are not, even in endemic areas).

Using lidocaine (subcutaneously or topically) may actually irritate the tick and prompt it to regurgitate its stomach contents. Once the tick is removed, wash the bite area with soap and water or with an antiseptic to destroy any contaminating microorganisms. The removed tick should be submitted for species identification.

For more information, see Tick Removal.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Routine prophylaxis after a recognized tick bite is not recommended. A guideline from the Infectious Disease Society of America recommends prophylactic antibiotic therapy for adults and children older than 8 years, using a single 200-mg dose of doxycycline (in children, 4.4 mg/kg up to a maximum dose of 200 mg/day) only if all of the following criteria are met [53] :

-

The attached tick can be reliably recognized as a nymphal or adult Ixodes scapularis

-

The tick has been attached for at least 36 hours, as determined by the degree of engorgement of the tick or certainty about the time of exposure to the tick

-

Prophylaxis can be started within 72 hours of the time the tick was removed

-

The local rate of infection of these ticks with Borrelia burgdorferi is at least 20% (unlikely outside of select areas in New England, the mid-Atlantic States, Minnesota, and Wisconsin)

-

Doxycycline treatment is not contraindicated

The species of tick is important because non-Ixodes ticks (and other insects), although they can contain the organism, are highly unlikely to cause disease. The one clinically relevant exception may be bites by Amblyomma americanum in the central and southern midwestern United States, but few data exist on treating these tick bites prophylactically.

Doxycycline is relatively contraindicated in children younger than 8 years and in pregnant women. Amoxicillin should not be substituted for doxycycline in persons for whom doxycycline prophylaxis is contraindicated, for the following reasons [86] :

-

The absence of data on an effective short-course regimen for prophylaxis

-

The likely need for a multiday regimen (and its associated adverse effects)

-

The excellent efficacy of antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease if infection develops

-

The extremely low risk that a person with a recognized bite will develop a serious complication of Lyme disease

Even in areas where about 15-30% of ticks are infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, tick bites rarely result in Lyme disease. Nevertheless, appropriate prophylaxis can significantly reduce that risk. [87] In a 2010 meta-analysis of trials in which patients with no clinical evidence of Lyme disease were randomly allocated to treatment or placebo groups within 72 hours after an Ixodes tick bite, the risk of Lyme disease in the control group was 2.2% compared with 0.2% in the antibiotic-treated group. [88]

Vaccination

In December 1998, the FDA approved a vaccine (LYMErix Lyme disease vaccine [recombinant OspA]) directed against the outer surface protein A (OspA) of B burgdorferi, after trials indicated efficacy. In 2002, this vaccine was pulled off the market by the manufacturer because of poor demand. [89] Patients who received this vaccine are no longer protected against Lyme disease, because the vaccine’s effect was not long lasting.

Work on Lyme disease vaccines has continued, however, and a candidate vaccine, VLA15, is currently in phase 3 human trials. [89] VLA15 is a multivalent, protein subunit vaccine that uses recombinant OspA from six different OspA serotypes of pathogenic Borrelia species, but does not contain the antigenic residues in OspA serotype 1 suspected to be responsible for some of the adverse effects reported with LYMErix. [90]

A novel approach to a Lyme vaccine uses messenger RNA (mRNA) to enhance the recognition of a tick bite and diminish transmission of Borrelia by targeting salivary proteins of Ixodes scapularis ticks. In a guinea pig study by Sajid et al, animals given lipid nanoparticle–containing nucleoside-modified mRNAs encoding 19 I scapularis salivary proteins and subsequently challenged with I scapularis developed erythema at the bite site shortly after ticks began to attach. The ticks fed poorly and detached early, thus providing protection against transmission of B burgdorferi. These researchers suggest that this approach could be used either alone or in conjunction with traditional vaccines for the prevention not only of Lyme disease, but potentially other tick-borne infections, as well. [91]

Consultations

In most patients with erythema migrans, no consultation is needed. However, consultation with appropriate specialists (eg, rheumatologist, neurologist, cardiologist) may be indicated to ensure that other diseases are not the cause of unusual presenting symptoms in a patient with a positive Lyme titer.

Difficulties can arise in choosing the appropriate antibiotic treatment regimen, especially in children or potentially pregnant women. An infectious disease consult is helpful in these situations. [92]

Consultation with a rheumatologist may be helpful in the evaluation and treatment of patients with persistent arthritis despite conventional antimicrobial therapy and those who present with fibromyalgia occurring after treated Lyme disease.

Consultation with a neurologist is recommended in patients with persistent or chronic manifestations of Lyme disease, such as chronic fatigue syndrome. In addition, in patients with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, neurologic disease is not uncommon and its presence alters the treatment plan; therefore, consultation is appropriate if neurologic signs or symptoms are present.

Consultation with a cardiologist may be indicated in patients with coexisting cardiac disease.

Long-Term Monitoring

Follow-up monitoring until all signs and symptoms have completely resolved is indicated for all patients with Lyme disease. In early Lyme disease, lack of prompt resolution should lead the physician to question the original diagnosis. Later manifestations tend to resolve much more slowly than early ones. Follow-up monitoring by the primary care physician or an appropriate specialist is indicated for patients with extracutaneous manifestations.

Patients with Lyme disease whose specific symptoms of Lyme disease (not symptoms of fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue) do not improve may need retreatment. Patients who plateau in their improvement may also need retreatment. Given the cost and convenience, a 30-day course of oral antibiotic therapy may be indicated before repeating intravenous therapy.

Repeat serologic testing is not indicated, because IgM titers may persist with treatment, and changes in IgG titers do not reflect the efficacy of treatment. That is, the standard serologic tests, with initial positive results, may remain positive for long periods and should not be used as a test of cure. Data suggest that C6-peptide may return negative results after treatment with antibiotics.

Follow-up may be of particular importance in patients with the chronic sequelae of the controversial post-Lyme disease syndrome. These patients’ condition may be refractory to conventional therapies.

-

Lyme disease. The bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi (darkfield microscopy technique, 400X; courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

-

Lyme disease. Magnified ticks at various stages of development.

-

Ticks are the most common vectors for vector-borne diseases in the United States. In North America, tick bites can cause Lyme disease, human granulocytic and monocytic ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, relapsing fever, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Colorado tick fever, tularemia, Q fever, and tick paralysis. Europe has a similar list of illnesses caused by ticks, but additional concerns include boutonneuse fever and tick-borne encephalitis. Lyme disease is one of the most prominent tick-borne diseases, and its main vector is the tick genus Ixodes, primarily Ixodes scapularis. Image courtesy of the US Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Lyme disease. Approximate US distribution of Ixodes scapularis. Image courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Lyme disease. In general, Ixodes scapularis must be attached for at least 24 hours to transmit the spirochete to the host mammal. Prophylactic antibiotics are more likely to be helpful if feeding is longer. This photo shows 2 I scapularis nymphs. The one on the right is unfed; the other has been feeding for 48 hours. Note its larger size and the fact that the midgut diverticula (delicate brown linear areas on the body) are blurred. Photo by Darlyne Murawski; reproduced with permission.

-

Lyme disease. Normal and engorged Ixodes ticks.

-

Amblyomma americanum is the tick vector for monocytic ehrlichiosis and tularemia. An adult and a nymphal form are shown (common match shown for size comparison). Image by Darlyne Murawski; reproduced with permission.

-

Approximate US distribution of Amblyomma americanum. Image courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

The soft-bodied tick of the genus Ornithodoros transmits various Borrelia species that cause relapsing fever. Photo courtesy of Julie Rawlings, MPH, Texas Department of Health. Relapsing fever is characterized by recurrent acute episodes of fever (usually >39°C). It is a vector-borne illness spread by lice and ticks. The spirochete species Borrelia is responsible.

-

The Ixodes scapularis tick is considerably smaller than the Dermacentor tick. The former is the vector for Lyme disease, granulocytic ehrlichiosis, and babesiosis. The latter is the vector for Rocky Mountain spotted fever. This photo displays an adult I scapularis tick (on the right) next to an adult Dermacentor variabilis; both are next to a common match displayed for scale. Photo by Darlyne Murawski; reproduced with permission.

-

Approximate US distribution of Dermacentor andersoni. Image courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Rhipicephalus ticks are vectors for babesiosis and rickettsial infections, among others. Image courtesy of Dirk M. Elston, MD. In typical practice, testing ticks for tick-borne infectious organisms is not generally recommended. However, healthcare practitioners should become familiar with the clinical manifestations of tick-borne diseases (eg, Lyme disease, especially those practicing in endemic areas) and maintain a high index of suspicion during warmer months. Ticks can be placed in a sealed container with alcohol if they need to be transported and identified.

-

To remove a tick, use fine-tipped forceps and wear gloves. Grasp the tick as close to the skin surface as possible, including the mouth parts, and pull upward with steady, even traction. Do not twist or jerk the tick because this may cause the mouth parts to break off and remain in the skin; however, note that the mouth parts themselves are not infectious. When removing, wear gloves to avoid possible infection.

-

Lyme disease. This patient's erythema migrans rash demonstrates several key features of the rash, including size, location, and presence of a central punctum, which can be seen right at the lateral margin of the inferior gluteal fold. Note that the color is uniform; this pattern probably is more common than the classic pattern of central clearing. On history, this patient was found to live in an endemic area for ticks and to pull ticks off her dog daily.

-

Erythema migrans, the characteristic rash of early Lyme disease.

-

Lyme disease. The thorax and torso are typical locations for erythema migrans. The lesion is slightly darker in the center, a common variation. In addition, this patient worked outdoors in a highly endemic area. Physical examination also revealed a right axillary lymph node.

-

Lyme disease. Photo of the left side of the neck of a patient who had pulled a tick from this region 7 days previously. Note the raised vesicular center, which is a variant of erythema migrans. The patient had a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction approximately 18 hours after the first dose of doxycycline.

-

Lyme disease. Classic target lesion with concentric rings of erythema, which often show central clearing. Although this morphology was emphasized in earlier North American literature, it only represents approximately 40% of erythema migrans lesions in the United States. This pattern is more common in Europe. Courtesy of Lyme Disease Foundation, Hartford, Conn.

-

Typical appearance of erythema migrans, the bull's-eye rash of Lyme disease.

-

Lyme disease. Bulls-eye rash.

-

Lyme disease. Photo of erythema migrans on the right thigh of a toddler. The size and location are typical of erythema migrans, as is the history of the patient vacationing on Fire Island, NY, in the month of August. No tick bite had been noted at this location. Approximately 25% of patients with Lyme disease are children, which is the same percentage of patients who do not recall a tick bite. Courtesy of Dr John Hanrahan.

-

Lyme disease. Multiple lesions of erythema migrans occur in approximately 20% of patients. A carpenter from Nantucket who worked predominantly outside had been treated with clotrimazole/betamethasone for 1 week for a presumed tineal infection, but the initial lesion grew, and new ones developed. He then presented to the emergency department with the rashes seen in this photo. The patient had no fever and only mild systemic symptoms. He was treated with a 3-week course of oral antibiotics.

-

Lyme disease. The rash on the ankle seen in this photo is consistent with both cellulitis (deep red hue, acral location, mild tenderness) and erythema migrans (presentation in July, in an area highly endemic for Lyme disease). In this situation, treatment with a drug that covers both diseases (eg, cefuroxime or amoxicillin-clavulanate) is an effective strategy.

-

Lyme disease. Borrelial lymphocytoma of the earlobe, which shows a bluish red discoloration. The location is typical in children, as opposed to the nipple in adults. This manifestation of Lyme disease is uncommon and occurs only in Europe. Courtesy of Lyme Disease Foundation, Hartford, Conn.

-

A rarely reported noninfectious complication for tick bites is alopecia. It can begin within a week of tick removal and typically occurs in a 3- to 4-cm circle around a tick bite on the scalp. A moth-eaten alopecia of the scalp caused by bites of Dermacentor variabilis (the American dog tick) has also been described. No particular species appears more likely to cause alopecia. Hair regrowth typically occurs within 1-3 months, although permanent alopecia has been observed.

-

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is found almost exclusively in European patients and comprises an early inflammatory phase and a later atrophic phase. As the term suggests, the lesion occurs acrally and ultimately results in skin described as being like cigarette paper. Courtesy of Lyme Disease Foundation, Hartford, Conn.

-

Blood smear showing likely babesiosis. Babesiosis can be difficult to distinguish from malaria on a blood smear.

-

Life cycle of the Ixodes dammini tick. Courtesy of Elsevier.

-

Lyme disease in the United States is concentrated heavily in the northeast and upper Midwest; it does not occur nationwide. Dots on the map indicate the infected person's county of residence, not the place where they were infected. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).