Sylvia Janicki doesn’t remember being bitten by a tick in 2014, but she did develop a bullseye rash—a hallmark sign of Lyme disease, the most common (and feared) infectious disease spread by ticks in the United States. Within 24 hours of the rash’s appearance, a doctor diagnosed the 29-year-old Seattle resident with Lyme. She was swiftly treated with a four-week standard dose of antibiotic therapy, which cured her flu-like symptoms.

Until it didn’t. A few months later, her headaches, fever, and fatigue came rushing back, along with head pressure and numbness and tingling in her legs. “I had a hard time walking half a mile to the market, which was alarming since, at that point, I had been running four to five miles a day regularly,” Janicki says. “That’s when the confusion amongst my doctors started. The standard knowledge is that once you’re treated with antibiotics, you’re fine,” she says.

In an effort to understand why she felt so terrible, Janicki’s doctors ordered a variety of imaging and blood tests, but they all came back negative. Multiple sclerosis, a disease of the central nervous system, was thrown out there as a possible diagnosis. She received another round of antibiotics from an integrative doctor. Her symptoms disappeared, only to return yet again.

Eventually, Janicki was referred to a “Lyme-literate naturopath” one year after her initial diagnosis of the disease. She was eventually told she was dealing with chronic Lyme.

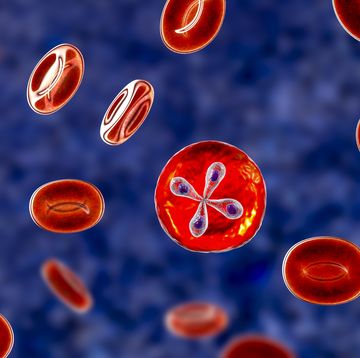

Transmitted through the bite of an infected blacklegged tick, Lyme disease stems from the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria, per the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). While 30,000 cases of Lyme are reported to the CDC each year, the actual number of people diagnosed is estimated to be much higher—up to 300,000. “This is a disease I believe to be an epidemic,” says Christine Green, MD, a San Francisco-based family medicine physician who specializes in treating Lyme disease.

So why is it, then, one of the most controversial topics in medicine? Unlike a standard Lyme diagnosis, chronic Lyme disease (CLD) is not an officially recognized illness and it’s a controversial lay term that many doctors don’t even use themselves. In fact, they’re divided on if it’s a “real” disease at all and some doctors have outspokenly called it a “fake diagnosis.”

What patients do know: Their symptoms are very real, and in some cases, completely disabling and life-stealing—so what exactly is going on?

When Lyme disease goes wrong

Lyme isn’t always an in-your-face disease. The infamous bullseye-shaped rash, like the one Janicki experienced, only appears in 70 to 80 percent of people who receive an infected bite—and it may not look like a bullseye at all in some people.

To compound the confusion, Lyme symptoms can easily wipe you out, but are so nonspecific that they’re difficult to catch before the illness advances. Christina Kovacs, 31, says she felt like she had a “summertime flu” shortly before entering college in 2006. “I spent a month sick in bed. I tested for mononucleosis at least three times during my first semester of college. I knew I didn’t feel well, but everyone kept telling me I was okay, so I trudged through it,” Kovacs says. “I came down with a fever, fatigue, chills, weakness, and migraines.”

Her doctors gave her a round of antibiotics, thinking that she might have strep or a bacterial illness. “These helped some, but when I finished the 7-day course, all the symptoms came back,” she says. Once again, she was prescribed more antibiotics. Eventually, the fever and chills went away, but fatigue and migraines persisted. Still, she didn’t get clarity about what was going on.

In most cases, when Lyme disease is readily diagnosed, a three to four-week dose of oral antibiotics like doxycycline or amoxicillin will clear it up, and you can go back to life as normal. But reports show that for 10 to 20 percent of those diagnosed with Lyme disease, mysterious symptoms—joint pain, unrelenting fatigue, brain fog—persist beyond the point doctors expect them to.

This is called post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS). Patients suffering from it were clearly diagnosed with Lyme disease—meaning they experienced a tick bite or the bullseye rash—and treated with antibiotics, but remain stuck with lingering symptoms that they just can’t shake. A new study in the journal BMC Public Health estimates that there will be two million cases of PTLDS by 2020.

But PTLDS is not interchangeable with chronic Lyme, which casts a wider net and can be used to describe cases where a B. burgdorferi infection was never officially diagnosed, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID).

That’s where things get dicey. People may be told they have CLD without proof they were ever bitten by a tick. Or they’re told that, absence of any other explanation, the default diagnosis is Lyme disease. And when you’re searching for validation, CLD can feel like the answer you’ve been looking for.

The problem with CLD symptoms

It’s that they’re common: Musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, headache, poor sleep, or low mood—all things that are ascribed to CLD—“these are symptoms that CDC studies show a fair amount of the adult population complains about,” says Paul Auwaerter, MD, clinical director in the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins Medicine and an expert on tick-borne diseases.

Kovacs spent years bouncing from specialist to specialist to try to tackle each problem as it came—the cardiologist after spells of dizziness and fainting, the GI doc for digestive problems. Because of that, “it was so easy to fall through the cracks,” she says. Her symptoms spanned everything from low blood pressure to joint pain to dizziness and confusion to clumsiness and migraines.

The Ashland, KY resident, who now runs the blog Lady of Lyme, wouldn’t be told she has chronic Lyme disease until September 2011, more than five years after falling ill. She never found a tick bite, but says she had spent time in the woods and never checked her body after.

This is where things get complicated: If you didn’t find an attached tick on your body, didn’t see a rash, or didn’t test positive for the bacteria, how can doctors be sure that you’re feeling run down, foggy, and achy because of Lyme? What if you live in a state where Lyme isn’t rampant?

“There can be a lot of explanations for why you’re tired, but I think doctors have labeled a fairly high percentage of people as having suffered from Lyme when there’s no clear reason to understand why it’s Lyme as opposed to another condition,” Dr. Auwaerter says. Fibromyalgia, multiple sclerosis, sleep apnea, anemia, and undiagnosed depression are all conditions that can mimic these unexplained symptoms.

The issue, says Dr. Auwaerter, is there’s not solid evidence behind diagnosing someone with Lyme based on these symptoms, and rushing to do so could lead to inaccurate diagnoses. However, that’s not to say that their suffering doesn’t exist. “People are looking for answers and often desperate for advice. These are very difficult-to-treat problems,” he says.

The challenges of testing

If you were diagnosed with Lyme disease, your doctor may have done so based on either two-tier testing (this detects the presence of antibodies in the blood, which can be found in the body a few weeks after infection with the bacteria) or you may have been diagnosed based on symptoms, like a clear bullseye rash.

However, there are limitations to testing, which range from blood and fluid sampling to brain imaging. “We don’t have a perfect test to identify an active B. burgdorferi infection,” says Brian A. Fallon, MD, head of the Lyme & Tick-Borne Diseases Research Center at Columbia University Irving Medical Center co-author of Conquering Lyme Disease.

Most notably, he says that selectivity and sensitivity in available testing deliver both false positives and negatives. On top of that, you need to be tested within the right window; do it too early or late and you may get also get a phony result. “This is incredibly confusing,” says Dr. Fallon, who adds that tests currently under development may help better identify active infection markers.

The story is even worse for people with persistent Lyme-like symptoms who have no test to determine what’s going on, thus opening the door for a CLD diagnosis with little evidence to back it up.

Then, there are doctors who simply don’t believe their patients, delivering a huge injustice to people who just want to feel like themselves again. “Eventually, my doctor said ‘I can’t help you anymore,’” Janicki recalls. Later, other doctors would tell her that her illness was a product of stress, depression, or the result of the rigors of grad school. “As a young woman experiencing non-specific symptoms, finding help was especially difficult. It’s very easy to dismiss women in their 20s,” she says.

Why antibiotics aren’t always the answer

Beyond testing, Lyme disease treatment has also presented its challenges, and a standard course of antibiotics doesn’t always nip an infection in the bud. “There are people who don’t fully recuperate after antibiotic therapy. And some people do have their health profoundly altered from the infection. That’s absolutely true, and we don’t completely understand why,” says Dr. Auwaerter.

In one 2017 study published in PLOS One, animal evidence suggests that B. burgdorferi can survive standard antibiotic treatment in some, as the bacteria may become tolerant and essentially hide in organs like the brain. The bug is smart, stealth, and as such, can be hard to detect and eradicate. “The big picture we’re starting to see is that some patients develop poor immune responses to infection and don’t do well with [standard] antibiotic treatment,” says study author Monica E. Embers, PhD, assistant professor in the division of bacteriology and parasitology at Tulane University.

What’s more, ticks are profoundly dirty, say some experts, meaning they might have the ability to infect you with more than one bacteria, something called “co-infection” (an idea that still many experts do not support).

Until targeted treatments are identified, patients—and often their doctors—don’t know what to do, but research from the NIAID shows that these people are, in fact, drowning in very real symptoms. They may suffer from neuropsychiatric problems or memory, verbal fluency, or speed of thinking issues (together known as “brain fog”) or suffer depression or anxiety that they didn’t have prior to Lyme, says Dr. Fallon.

So, what then? The answer is certainly not more antibiotics. “Most patients I see have already been on a tremendous amount of antibiotic therapy in attempt to eradicate the cause of their illness,” says Dr. Fallon.

Finding the right treatment

The challenge now is to move beyond antibiotics into more symptom-based approaches, like those that treat depression or anxiety or that target neurological pain. But often patients hesitate. “They’ve experienced such traumatic invalidation by the medical community that they’re reluctant to try symptom-based medicine because they feel like if they do, it’s giving into what doctors have told them all along, that it’s not Lyme. It becomes an obstacle to getting optimal care,” says Dr. Fallon.

Many also turn to alternative therapies that are not supported by scientific evidence, including oxygen, energy, or heavy metal therapy, off-label use of medications, or even stem cell transplantation. A 2015 paper in Clinical Infectious Diseases came down hard on these treatments, calling them unproven and possibly dangerous.

Phillip Baker, PhD, the executive director of the American Lyme Disease Foundation (ALDF) was one author on the report. He’s very forward with his rejection of CLD and many of the doctors that diagnose it. Without it being a recognized disease, it’s difficult to get insurance coverage, so patients are stuck paying out of pocket for treatment.

Baker says that these doctors profit off of Lyme, and that some patients shell out $70 to $80,000 in a futile search of solutions, particularly after a long-term course of antibiotics has failed. One study in PLOS One, for example, found that people with PTLDS have $4,000 higher health care costs and endure more doctor visits compared to those without PTLDS.

“I had to do crowdfunding twice [in order to pay for treatments],” says Seattle-based Kat Woods, 35, the blogger behind HopeHealCook, a site for people suffering from Lyme or other chronic illnesses. Woods can remember being bit by a tick at age 13, but wasn’t diagnosed with Lyme at the time. She suffered from terrible neurological symptoms that got incorrectly flagged as a rotation of diseases, including mental illness, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia.

By the time she was 23 she was on “handfuls” of psychotropic drugs. “At that point, my body gave out,” says Woods. It wasn’t until she connected with a naturopath that she felt her pain was truly acknowledged. Then, she received her answer: Lyme, in addition to other co-infections. Woods later moved to Seattle specifically to pursue medical care with a doctor specializing in “complex chronic illness” (a moniker for a “Lyme-literate doctor," she says).

The road to wellness for Woods spanned years—and a lot of money. “I’m so grateful and upset that crowdfunding is an option. We’re people who are already so sick and it’s completely overwhelming to have to go out and, as I call it, do digital panhandling. We have to beg for money from strangers because the government and doctors don’t recognize that we have a real illness,” she says, adding that “almost all” of her friends with Lyme have had to turn to crowdfunding to finance treatments.

Understanding the road forward

A common refrain: Chronic Lyme disease is an easy answer to a seemingly-impossible-to-solve problem. “The dialogue over CLD provokes strong feelings, and has been more acrimonious than any other aspect of Lyme disease,” Paul M. Lantos, MD, of Duke University, writes in a 2016 paper in the Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. What is clear is that patients are in very real pain, no matter if the cause is Lyme or not, he says. That is something both sides agree on.

But patients are caught in the middle, the medical community is failing them, and they’re suffering for it. It’s difficult to be your own advocate when you lack the energy to champion your health. “The problem is that patients aren’t getting taken care of,” says Dr. Green.

She herself doesn’t use the term “chronic Lyme,” rather she calls it “late Lyme,” which refers to Lyme disease that was missed or treated ineffectively. “[These chronic symptoms are] causing a lot of illness and morbidity, loss of productive hours, and quality of life,” she says.

Still, many patients report that their own doctors wave their hand, telling them their lingering symptoms don’t really exist. They may suspect they have a terminal illness like cancer, and start scrambling, jumping from doctor to doctor to find help. On average, these patients see seven doctors, seek medical help 20 times a year, and have to travel more than 50 miles to do so. The logistics alone are an incredible burden.

“We wouldn’t do this in any other disease,” says Dr. Green. “We’d change our treatment course or investigate what’s going on—not say ‘oh it’s all in your head.’”

How to get the help you need

Whether or not the problem is Lyme disease, advocating for your health is an important and tall task when you feel sick. Here’s how to navigate the waters and find help.

Stay updated on the latest science-backed health, fitness, and nutrition news by signing up for the Prevention.com newsletter here. For added fun, follow us on Instagram.

Jessica Migala is a health writer specializing in general wellness, fitness, nutrition, and skincare, with work published in Women’s Health, Glamour, Health, Men’s Health, and more. She is based in the Chicago suburbs and is a mom to two little boys and rambunctious rescue pup.