AMC is facing a situation. After having reframed television with two shows that are as good as any television shows that have ever been produced — Mad Men and Breaking Bad — its amazing run is coming to an end. Low Winter Sun, coming out this Sunday after the return of Breaking Bad, is its big attempt at a replacement. Unfortunately, it feels that way. Low Winter Sun feels exactly like second-rate Breaking Bad. AMC is the victim of its own success.

The timing for Low Winter Sun, set in Detroit, is nearly perfect. Since its bankruptcy, Detroit has passed beyond its status as a symptom of American manufacturing decline, into a symbol of a world utterly transformed. Detroit is now smaller than Columbus, Ohio, and the Washington Post is worth less than a single painting by Cezanne. The future is now, and it isn't particularly pretty. In Low Winter Sun, the city is splendid ruins, and the dereliction of the atmosphere is played up perfectly. It's not so much disaster porn, as it is a real-life post-apocalypse. It reminded me of 28 Days Later. The background appears far too big for the characters inside it. Every shop is chaperoned by boarded-up places. Every vacant lot contains the spectral presence of the crowds that once filled it. Practically every shot contains the question: Where are all the people?

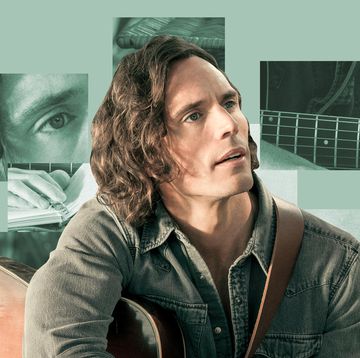

Against this background, the plot is savage, even by the standards of contemporary television. It makes The Wire look naively optimistic. The opening credits have a dog with a rat in its mouth, which is pretty much the happiest moment in the whole show. At least the dog is winning. Even in the first two episodes, the line between the police and the criminal underworld is more or less erased. Mark Strong stars as Frank Agnew, a cop whose first act is to murder another cop at the prompting of a fellow cop. The criminal underclass operates at the lowest possible stakes. Even in shows like The Wire, the drug dealers are dignified by the scale of their operations. Walter White ships to the Czech Republic. The dealers in Low Winter Sun kill for a couple of kilos, and have only moved on recently from stripping copper wires out of buildings. The main problem for everybody involved is that there's not enough to steal anymore. The stakes get lower and lower.

The golden age of television appeared in a world where the decline of American power became an intellecutal commonplace. The pilot of The Sopranos had Tony confess to Dr. Melfi: "It's good to be in something from the ground floor. I came too late for that and I know. But lately, I'm getting the feeling that I came in at the end." All of the great shows have men who are basically good faced with a world that is crumbling. That's been the formula in The Sopranos, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad. Low Winter Sun is trying to repeat their successes with a heightened intensity: These are men trying to deal with a world that's already fallen apart.

The reason we love those shows is that they're so original. We had never seen anything like them before. Low Winter Sun is derivative of great television, but still derivative. There's a lot of The Wire (cops and robbers in a broken city), a good amount of The Killing (season-long murder case), with a dash of Breaking Bad (mechanics of a drug empire) and a touch of Justified (cops with personal systems of vengeance). Despite its extreme currency, Low Winter Sun is beautiful but feels like a show whose time has passed, just like the city of its setting.

PLUS: Read More Stephen Marche on The Culture Blog >>

Follow The Culture Blog on RSS and on Twitter at @ESQCulture.