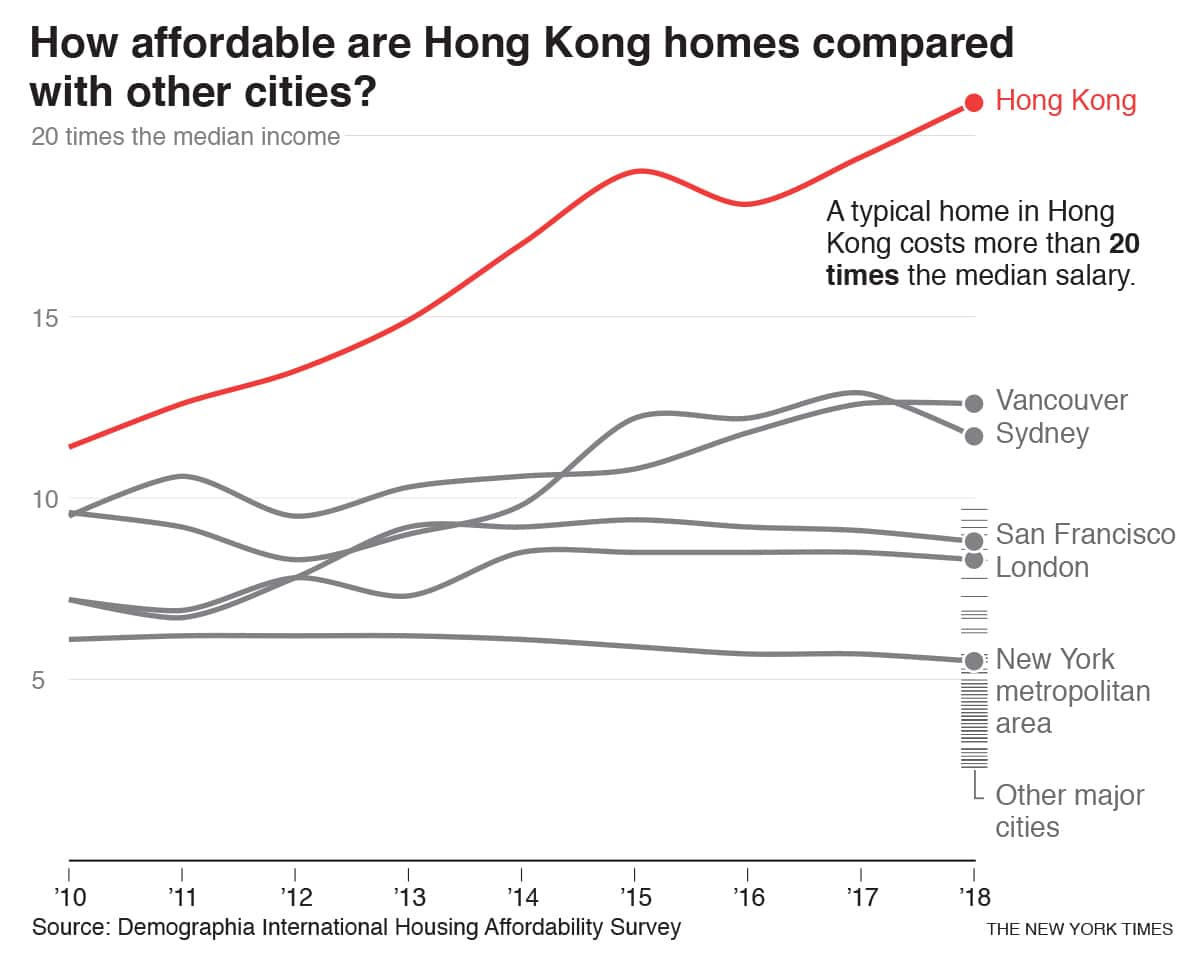

Above: How do people in Hong Kong afford housing when the costs are almost as high as their income?

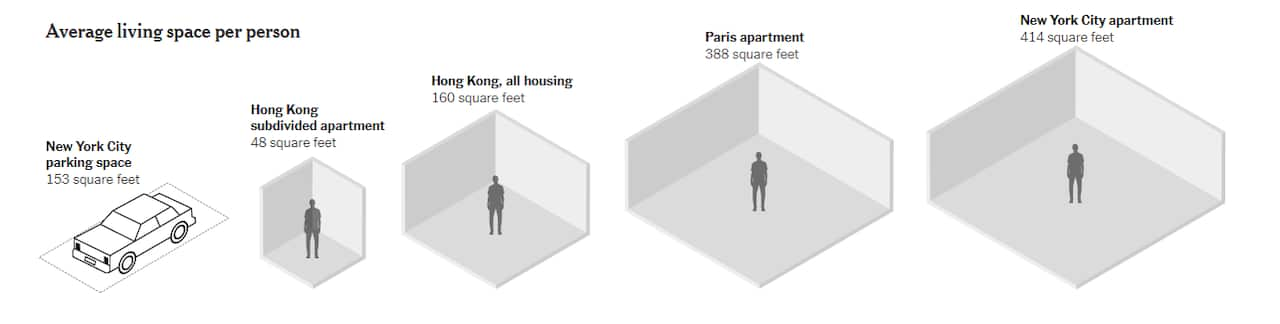

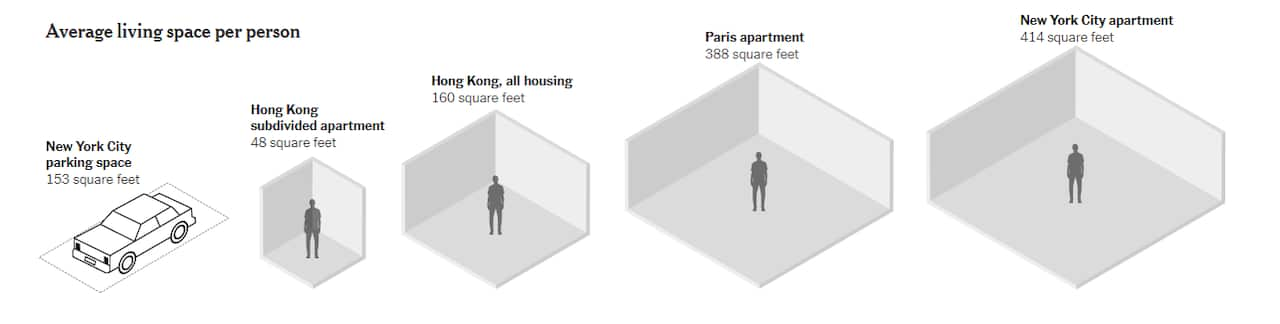

Rents higher than New York, London or San Francisco for apartments half the size. Nearly one in five people living in poverty. A minimum wage of US$4.82 an hour.

Hong Kong, a semi-autonomous Chinese city of 7.4 million people shaken this summer by huge protests, may be the world’s most unequal place to live. Anger over the growing power of mainland China in everyday life has fuelled the protests, as has the desire of residents to choose their own leaders. But beneath that political anger lurks an undercurrent of deep anxiety over their own economic fortunes — and fears that it will only get worse.

“We thought maybe if you get a better education, you can have a better income,” said Kenneth Leung, a 55-year-old college-educated protester. “But in Hong Kong, over the last two decades, people may be able to get a college education, but they are not making more money.”

Leung joined the protests over Hong Kong’s plan to allow extraditions of criminal suspects to mainland China, where the Communist Party controls the courts and forced confessions are common. But he is also angry about his own situation: He works 12 hours a day, six days a week as a security guard, making US$5.75 an hour. He is one of 210,000 Hong Kong residents who live in one of the city’s thousands of illegally subdivided apartments. Some are so small they are called cages and coffins.

He is one of 210,000 Hong Kong residents who live in one of the city’s thousands of illegally subdivided apartments. Some are so small they are called cages and coffins.

The widening wealth gap in Hong Kong is being felt in the most fundamental way: where people live. Source: The New York Times

His room, by comparison, is a relatively spacious 100 square feet to sleep, cook and live. He sometimes struggles to make his $512 a month rent after paying for food and other living costs.

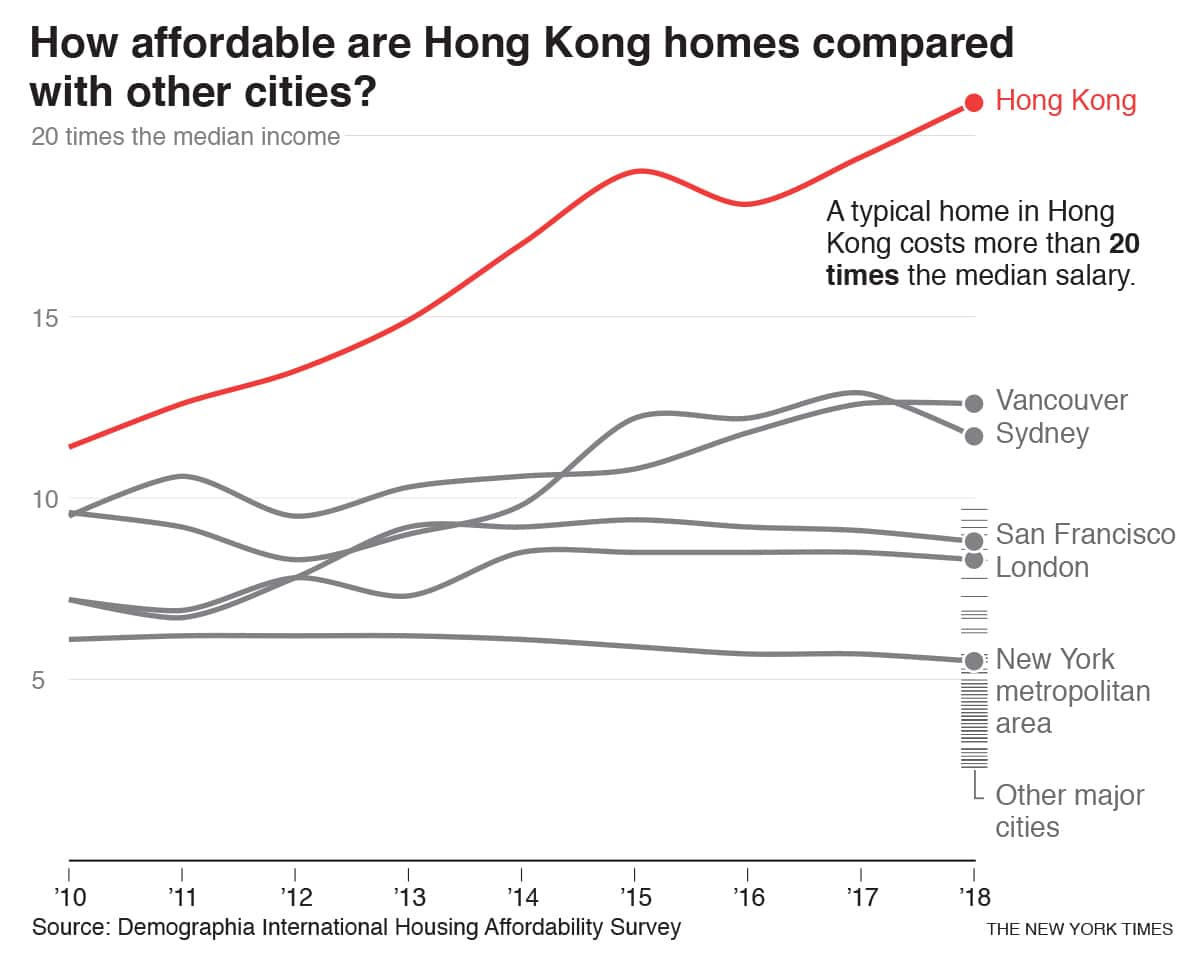

The numbers are striking. Hong Kong’s gap between the rich and the poor is at its widest in nearly half a century, and among the starkest in the world. It boasts the world’s longest working hours and the highest rents. Wages have not kept up with rent, which has increased by nearly a quarter over the same period. Housing prices have more than tripled over the past decade. The median price of a house is more than 20 times the annual median household income.

These issues were at the fore five years ago, when protests known variously as Occupy Central or the Umbrella Movement shut down parts of the city for weeks. Similar protests, such as the yellow vest movement in France, echo worries that a booming global economy has left behind too many people.

Today, protesters are focusing on the extradition bill, which Hong Kong leaders have shelved but not killed, and a push for direct elections in a political system influenced by Beijing. Hong Kong, a former British colony, operates under its own laws, but the protesters say that the Chinese government is undermining that independence and that the leaders it chooses for Hong Kong work for Beijing, for property developers and for big companies instead of for the people. Supporters of Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s top official, say she is trying to fix the city’s problems, though they acknowledge she has made missteps.

Supporters of Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s top official, say she is trying to fix the city’s problems, though they acknowledge she has made missteps.

Hong Kong's cost of housing has outgrown the average salary. Source: The New York Times

The long term solution, pro-Beijing officials say, is greater integration with the mainland, not less. Young people could take advantage of a program in which the Hong Kong government helps entrepreneurs to set up a business in the Greater Bay Area, a new economic zone that links Hong Kong with the mainland, said Felix Chung, who leads the pro-Beijing Liberal Party in the Legislative Council, the city’s lawmaking body.

“What’s the big deal if you have to travel from Zhuhai to Hong Kong?” Chung said, referring to a nearby Chinese city that is part of the program. “The Hong Kong people are spoiled,” he added.

For Philip Chan, those responses show how out of touch Hong Kong’s leaders have become. A 27-year-old protester and nurse at a public hospital, Chan still lives with his parents and shares a bunk bed with his 30-year-old sister. He sleeps on the bottom.

“The Chinese government cannot guarantee us anything. Take for example freedom of speech,” Chan said, citing Beijing’s blocking of internet apps like Facebook and WhatsApp. “How can we live?”

Housing lies at the root of many of the frustrations. So many people are priced out of the housing market that it is unusual to meet a young adult who does not still live with parents or family members.

“Many Hong Kong people face serious financial problems like the high price of housing,” Chan said. “They try to work hard but they cannot earn enough money to have a better living condition. They cannot see their future so they are frustrated.”

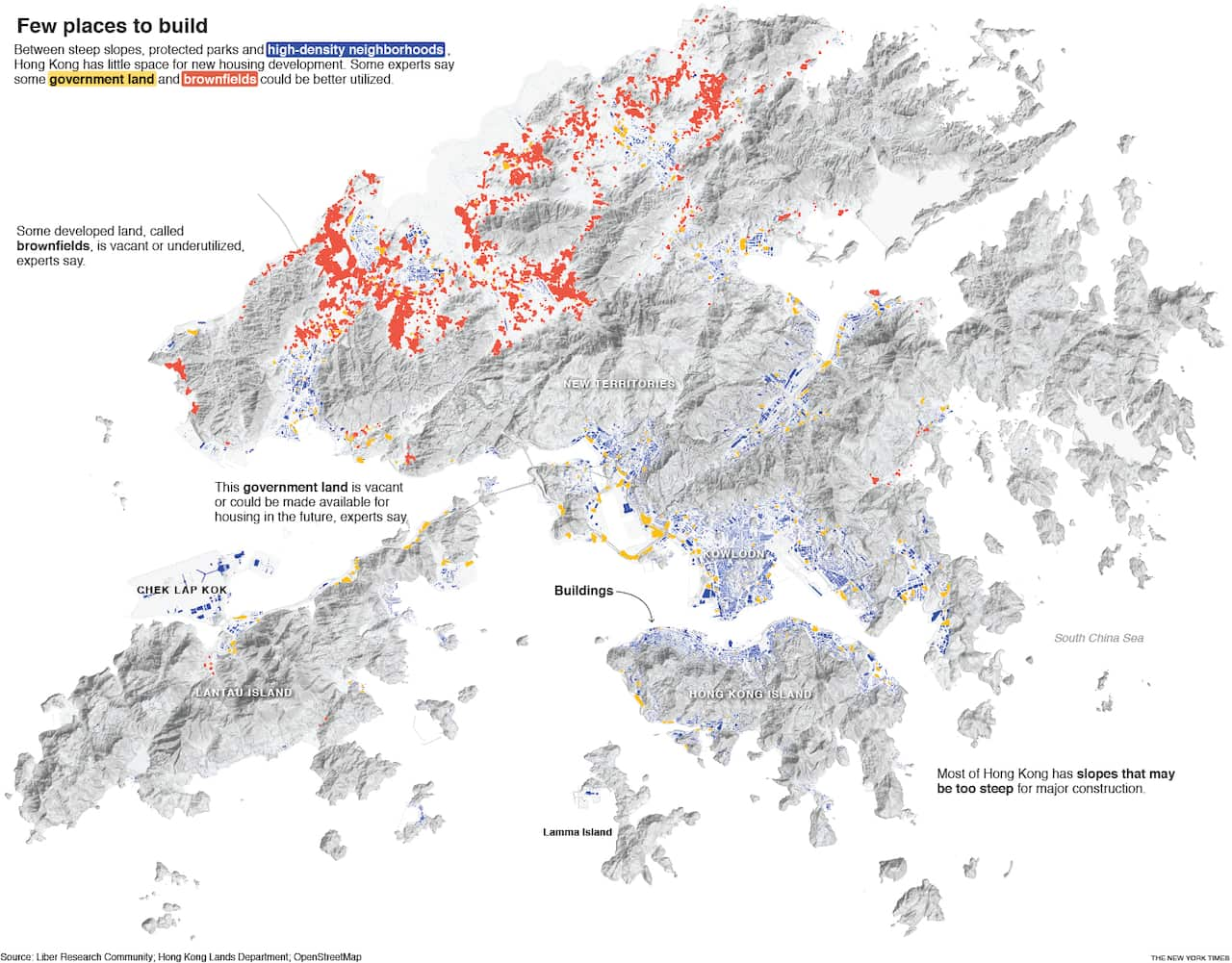

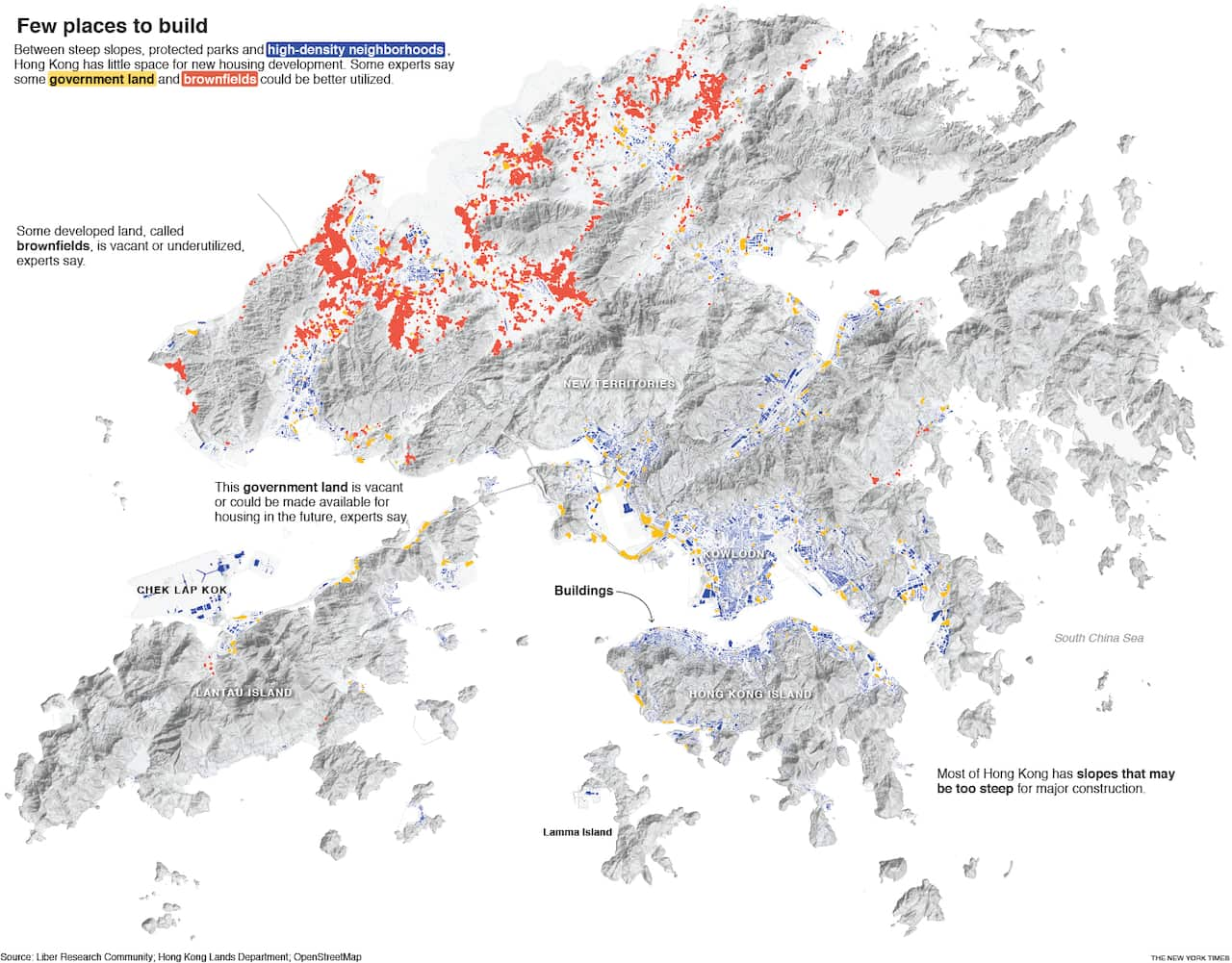

Perched on a series of islands and a swath of mountainous land descending from mainland China, Hong Kong already has relatively few places to build.

“The whole system is totally controlled by the vested interests of the elite,” said Cheuk-Yan Lee, the general secretary of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, a supporter of the protest movement. The government has also favoured wealthy mainlanders, believing that Chinese buyers could push up property values and make Hong Kong households feel richer. Hong Kong officials loosened limits on mainland investment after protests in 2003 against a contentious proposal that would have prohibited sedition, subversion and treason against China. Though the proposed bill was defeated, the overall result was a surge in property prices that enriched homeowners but priced a generation of people out of the market.

The government has also favoured wealthy mainlanders, believing that Chinese buyers could push up property values and make Hong Kong households feel richer. Hong Kong officials loosened limits on mainland investment after protests in 2003 against a contentious proposal that would have prohibited sedition, subversion and treason against China. Though the proposed bill was defeated, the overall result was a surge in property prices that enriched homeowners but priced a generation of people out of the market.

Source: The New York Times

“Many young people see there is little way out economically and politically, and it is the background of their desperation and anger at the status quo,” said Ho-fung Hung, a political-economy professor at Johns Hopkins University.

The city’s affordable housing program has not kept up.

Currently, more than 250,000 people are waiting for access to public housing. The number could be even higher, but Hong Kong officials have kept the cut-off at income of less than $12,000 per year. The critics say city officials refuse to change the threshold because it would mean Hong Kong would have to build even more public housing.

“The government requirement for eligibility for public housing is not realistic in terms of people who are living in poverty,” said Brian Wong at Liber Research Community, an advocacy group.

Wages have not kept up either, particularly at the low end. Hong Kong’s minimum wage is the equivalent of $4.82 an hour, a figure the government updates every two years. A number of non-profit organisations have called on the government to raise this to $7, which the British charity Oxfam calculated was a “living” wage for the city based on the average household cost. Lawmakers point out the latest increase in minimum wage earlier this year was the biggest since Hong Kong put in place a statutory minimum. But they also emphasise the importance of keeping Hong Kong competitive for foreign companies. Corporate tax in Hong Kong is among the lowest for major global cities.

Lawmakers point out the latest increase in minimum wage earlier this year was the biggest since Hong Kong put in place a statutory minimum. But they also emphasise the importance of keeping Hong Kong competitive for foreign companies. Corporate tax in Hong Kong is among the lowest for major global cities.

Critics of Hong Kong's government say officials want to avoid building more. Source: The New York Times

Many of the protesters say direct elections would give them a greater say in these crucial economic matters.

One protester, Roger Cheng, a 52-year-old consumer products salesman, was marching peacefully on July 1 when another nearby group began to ram metal rods through the glass doors of the Legislative Council. Like others around him, he was unwilling to oppose the violence.

“We prefer a more peaceful way of protesting,” Cheng said. “But we do not oppose the more radical way, because the Hong Kong government is not responsive at all.”