‘I consider myself Korean’: Koryo Saram, ethnic Koreans in Central Asia, keep their roots alive

Today, there are an estimated 500,000 Koryo Saram scattered across several former Soviet Union states.

At the Hambak village in Incheon, South Korea, where more than 5,000 Koryo Saram - ethnic Koreans from Central Asia - live, some streets and storefronts are named in Russian.

ALMATY, Kazakhstan: When she was a child, Ms Elena Kim thought she was Russian because she spoke Russian, a national language in Kazakhstan where she lives, fluently. Her grandparents were from Russia as well.

She remembers vividly the day she found out about her ethnic roots.

She had just returned home from kindergarten, she recalled.

“(My mother) told me I am actually Korean, not Russian, and that came as a shock to me. I felt like an alien since we didn't really have Korean people around back then,” Ms Kim told CNA.

She is among an ethnic Korean community living in Central Asia, who refer to themselves as Koryo Saram or Koryo-ins.

Her Korean grandparents settled down in Vladivostok in far-eastern Russia in the early 19th century where they had gone in search of greener pastures, but were later forcibly deported to Kazakhstan, which was part of the Soviet Union before its collapse.

In the early 1860s, fewer than 100 Koreans – mostly farmers from the northeastern province of Hamkyung, which is now part of North Korea – made their way to Russia in search of land and better living conditions, said researcher Hwang Youngsam from the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in South Korea.

“It was due to survival. They had to live. At least there was lots of barren land there and so they were able to grow crops and eat them. So that was good for them. That was the main reason,” said Dr Hwang.

By 1917, after Japan annexed Korea, their numbers grew to about 100,000.

When Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was worried that the Koreans in Russia would act as spies for Japan and deported them mainly to bordering Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

It was a brutal resettlement, with 172,000 Koreans transported in train wagons over just three days. Many died from starvation and harsh conditions.

Ms Kim said: “Most of these people didn't even make it. So we are the lucky ones – descendants of the survivors.”

Today, there are an estimated 500,000 Koryo Saram scattered across several former Soviet Union states.

SEARCHING FOR THEIR ROOTS

As she grew up, Ms Kim became interested to find out more about the origin of Koryo Saram and the history of her grandparents.

She traced her grandfather’s life back to Khabarovsk Street in Vladivostok, where he lived when he was 15 years old.

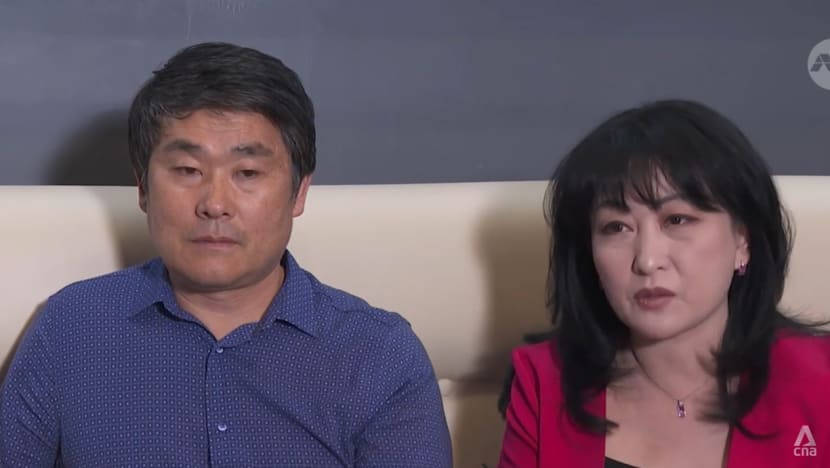

Last year, Ms Kim visited the Russia port city with other Koryo Saram, including her husband Sergei Kim, whom she now runs a Korean restaurant with in Kazakhstan’s largest city Almaty.

The Kims were both born in Kazakhstan – like their parents – and have lived there all their lives.

Most Koryo Saram cherish and preserve the Korean part of their identity. However, Korea is a foreign land to them.

“We follow our customs and try to keep alive traditions that have been passed down to us from generation to generation. We try to pass it down to our children as well. But unfortunately, over time these traditions have either changed or disappeared,” said Mr Kim.

Their 19-year-old daughter Alisa feels a deeper connection with Korea despite being born in Kazakhstan, and speaking only Kazakh and Russian.

“In general, I consider myself Korean. I present myself as a Korean. I would love to visit Korea to learn more about my motherland,” she said.

RETURNING TO THEIR ROOTS

While Alisa dreams of the day, some Koryo Saram have already made it happen.

Ms Irina Kim travelled from Uzbekistan, where she was born and raised, to South Korea 15 years ago.

“My grandmother raised me and I heard from her lots of stories about Korea, how there are lots of mountains and beaches. I always wondered if I’d get the chance to visit one day,” she told CNA in Korean, which she picked up in South Korea over the years.

It was through a friend in Uzbekistan that she learnt of a way to enter and live in South Korea, which is typically difficult as a special visa is required.

She made the journey alone. Although she had never been there, she was not afraid because she felt a sense of familiarity from the stories she had heard.

She initially hoped just to make enough money to send back home to her two children.

However, she accomplished much more. She now runs four flower shops and her two children have also moved to live with her in South Korea.

Two of her shops are in Incheon, a city northeast of Seoul, where she lives. The city houses a large community of Koryo Saram. More than 5,000 live in Hambak village, where signs in Russian line the streets. Her other shops are in Ansan in Gyeonggi province, another area where a large community of Koryo Saram live.

Ms Irina Kim and her children are among more than 100,000 Koryo-ins mainly from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan living in different parts of South Korea. Most Koryo Saram enter South Korea through a preferential employment permit for overseas ethnic Koreans known as the H2 visa.

Most of the H2 visa holders work in agriculture, fishery, manufacturing, construction and certain service sectors.

Experts said having a Korean background may not make it any easier for Koryo-ins and other overseas ethnic Koreans seeking to resettle in South Korea.

To improve the situation, Mr Kim Dae Ho runs a community centre in Hambak village where he conducts programmes that allow people from different nationalities to better understand one another.

“We are trying to provide ways for the Koryo-ins and South Koreans to meet. If they don’t have contact, there can be misunderstandings and conflicts. They have to meet, have arguments if needed or have meals together so they can resolve any misunderstandings. That’s why we run the various programmes here,” he said.

For Ms Irina Kim, South Korea feels like home.

“In the past, I didn’t belong anywhere. I didn’t feel like I had a hometown. But now I know my place is here,” she said.

KEEPING THE KOREAN CULTURE ALIVE

Some Koryo Saram who remain in Central Asia are doing their part to keep Korean culture alive.While most do not speak any Korean, Ms Zoya Kim is an exception.

The 70-year-old who specialises in traditional Korean dance and singing, was born and raised in Kazakhstan by her artist parents who instilled in her a love for Korean culture.

“We are Koryo people. We are far away from our motherland but our role here is to help protect and develop our culture and art. I think that's very important. We are proud of that. Our parents built this and so we have to preserve this,” the 70-year-old told CNA in Korean.

Among others keeping the Korean language alive in Central Asia is teacher Hur Seon-Haeng who was one of the first to start teaching the subject in Central Asia.

His journey to his career in a foreign land started when he visited Uzbekistan capital Tashkent in 1992 shortly after the country gained its independence and formed diplomatic ties with South Korea, where he had studied and graduated.

On the trip, he was intrigued by the existence of this group of ethnic Koreans in the former Soviet territories. He fell in love with teaching and the city, and set up a language school there in 1992.

“They speak the Koryo language a bit at home. But because they speak the Russian language when outside, many felt they should know their mother tongue. So when the institute was established, many showed interest," Mr Hur said.