Jordan Spieth's win on Sunday at the RBC Heritage was emblematic of his entire career. It contained myriad twists and turns -- including a bizarre, off-the-beaten-path golf cart ride to the first playoff hole -- and ultimately ended with a "wait, how in the world is he holding the trophy?" final act. This is largely who Spieth has been for the last nine years, which has made him both a joy to cover and a nightmare to root for but never -- I mean never, no matter the circumstances -- inconsequential to watch.

The win for Spieth is the 13th of a career that has been both longer and shorter than it feels like it has been. It sets him up for a hopeful summer in which he'll have two hometown events to go for, a grand slam attempt at Southern Hills and, ethe grandaddy of them all, an Open Championship reprise at the 150th edition of that event this summer at the Old Course, where he nearly took home his third straight major back in 2015.

In light of what went down on Sunday at Harbour Town and what's ahead for Spieth over the next three months, I jotted down a few lingering thoughts on a win that probably shouldn't have been and how we should feel about what it foreshadows this summer.

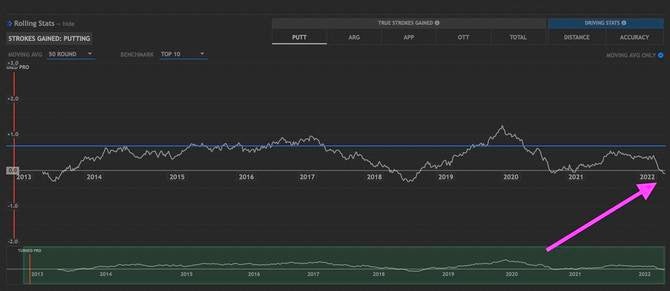

1. We need to talk about Cameron: Not Spieth's coach, Cameron McCormick, that is, but the flat stick. The Scotty. It was bad last week -- Spieth said he won the tournament without his putter, which was mostly true -- but it's not as if that's an anomaly in 2022. This was the sixth time in his last eight stroke-play tournaments in which he's lost strokes to the field in that category, and Data Golf shows that his 50-round rolling average is nearly as bad as it's ever been since he turned pro back in 2013.

He's putting at worse than a PGA Tour average clip, and none of the granular data is particularly encouraging. He's outside the top 100 on the PGA Tour in putts made from inside 10 feet, from 10-15 feet and from 15-20 feet. The saving grace, if you want to call it that, is his performance from 20-25 feet, where he's 82nd. Beyond 25 feet, it's back up to 162nd. The encouragement in all of this is that his approach putt performance ranks 26th on Tour this year, which reminds me of this great Justin Thomas quote from the Masters two weeks ago.

"He's got the best speed of putter I think I've ever seen," said Thomas. "You look at all his putts, especially all of his midrange putts, every single one of them goes in with the exact same speed. They don't hit the back of the hole. They're probably going to go anywhere from 6 to 12 inches past the hole. I don't think people realize how hard that is and how good that is to consistently do that every single time."

So the problem for Spieth has been not that he's not lagging well, but that he's not scoring well, which, when paired with good ball-striking is traditionally the way to win a PGA Tour event.

2. The ball-striking is coming around: After starting the year quite poorly, Spieth has only had one negative ball-striking event in his last seven. Unfortunately for him, that was at the tournament he craves the most and meant he was firing up Air Spieth on Friday evening to go home early from Augusta for the first time in his career. The strange part for Spieth right now is that he's driving it as well as he ever has in his career -- at least statistically -- and putting it far worse. Spieth is losing nearly two strokes per event with his putter, and while he's not likely to ever be the putter he was in his halcyon days of 2015-17, he's never had a full season where he was worse than PGA Tour average. It stands to reason that, even though the pre-shot routine engenders all kinds of angst, a Spieth return to baseline this summer on the greens could result in a lot more contention than we've seen to start 2022.

"I've been hitting the ball really, really well all spring, better than I did last year, and I just haven't been scoring," said Spieth on Sunday. "So I just, I put in a lot of hours on the putting green this week, and to be honest, if it helped incrementally, it was just enough. I've got a lot more work to do. I've been putting a lot of work into my full swing, and that certainly takes away some of the time you put into other parts of your game, including putting"

3. He probably should not have won: This was the strangest part about Sunday. When he finished at 13 under with a handful of groups behind him, it had the feel of somebody who closed nicely and could take some momentum into his next start. Then the field started fizzling out, and suddenly Spieth was shaking hands with his Ryder Cup teammate, Patrick Cantlay, on the 18th tee box and caddie Michael Greller was searching for his caddie bib. Here's the benefit of getting yourself close on the PGA Tour week in and week out: you're going to lose some you should have won and win some you should have lost. Spieth has experienced the former in the past but the latter came true on Sunday.

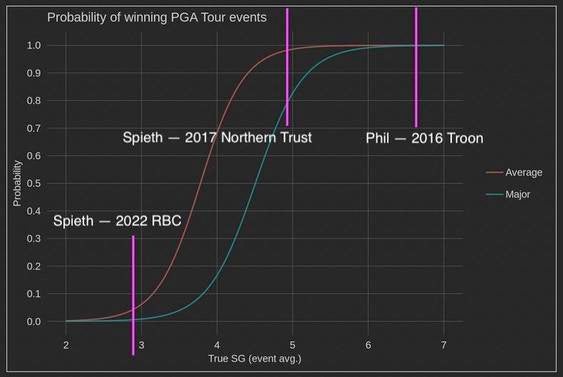

According to Data Golf, Spieth's 2.91 true strokes gained against the field wins a regular PGA Tour event around 5% of the time. It's rare to win a tournament with less than three strokes gained per round during a week. This can go the other way, too. In 2017, Spieth gained nearly five strokes a round at The Northern Trust, which ensures a PGA Tour win nearly 100% of the time (this field, however, was probably closer to major championship level). He lost to Dustin Johnson in a playoff. The most extreme recent example of this is Phil Mickelson's performance at the 2016 Open Championship. Lefty gained 6.6 (!!) strokes per round on the field -- which ensures a major win 99.9% of the time -- but he lost to Henrik Stenson by three (!).

In a career like Spieth's (or Mickelson's), this tends to even out over time, but it's fair to say Spieth stole one on Sunday at Harbour Town.

4. The Old Course: There was a lot of chatter on Sunday about how next year's Masters falls on Easter, a holiday upon which Spieth has won two straight events, and the PGA Championship, where Spieth will go for the career grand slam next month. However, it's the 150th Open Championship at the Old Course at St. Andrews that I want to discuss. This is Spieth's playground. He's destroyed at Opens, including five top 20s in his last six starts -- with one of those a near-miss at the Old Course in 2015 when he took that year's slam to the 71st hole of the third event and missed out on a playoff by a single stroke. Putting woes may travel -- he missed a short one on the last hole of his third round last year before falling to Collin Morikawa on Sunday -- but Spieth contains more mysticism than most in a game and on a course that seems to disproportionately (and inexplicably) reward it. Barring a bad-weather draw, he's almost certainly going to contend for what will be the biggest and most historically important event of 2022.

5. Who is he? I spend a lot of time and energy thinking about this question, but it is my job to have an answer. Yet after nine years of covering him, I'm still not sure I know. Surely he's not the guy winning at the Tiger Woodsian clip he won at in 2015. But just as surely he's not the lost boy who couldn't find the clubface in 2019 and 2020. He is impossible to quit but just as impossible at times to believe in. He defies understanding. Players with an historically great singular skill like Rory McIlroy and Collin Morikawa make more sense. When you watch Rory hit drives, you understand his path. When you see Morikawa flush approach shots, his future is within the realm of understanding. The one thing Spieth has been known for, albeit sometimes undeservedly so, has become his greatest liability. He doesn't seem to possess any elite skills at the moment, and on top of that, he is painful to watch in so many different ways. Nothing adds up.

Yet he wins. There is an enticing humanity to his game (and his persona) that tantalizes all who care to enter the ring with him. Like a lumpy fighter with nothing but a nose for survival, he's just trying to make it to the end of the round ... and the week. And he often has. Spieth has won nearly 6% of his 226 PGA Tour events across what is already a hall of fame career. While the last four years have not been as bountiful as the first half decade, hope still dangles out there somewhere in the future. Because like many who have toiled before him, he possess a game that is as dangerous to him as it is to the rest of the field. But like few who have ever done it, his desire to be great is almost peerless. The one constant in his career has been this: though we cannot (and probably will not) ever figure him out, it matters very little because he always seems capable of figuring it out, often when everyone least expects it.