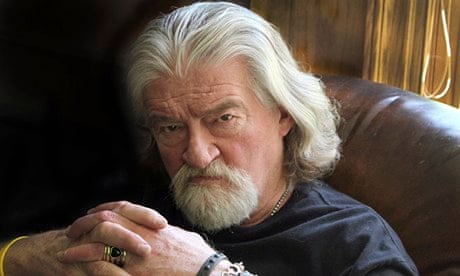

At 68 years old, a survivor of throat cancer, and with only one produced screenplay to his name since 1997, Joe Eszterhas has done the unthinkable: he's become a scriptwriting teacher. Well, not exactly – he's on his way to London to deliver a headlining lecture at the London screenwriters' festival – but anyone who has even the smallest familiarity with his books will know the contempt in which he holds teach-yourself-screenplay-writing gurus such as Robert McKee.

"Wannabe screenwriters sorely lack getting the truth from these so-called scriptwriting teachers," says Eszterhas, his post-cancer voice gravellier than ever. "McKee is the perfect example: he's had one TV movie made, and yet he pontificates on how to write scripts." He also has beef (one that's been going for decades, it seems) with other big-name scriptwriters, accusing them of "falsities"; he doesn't think much of William Goldman's stock anecdote that he pretended to take script notes from Dustin Hoffman, or Ron Bass's stated mission to "serve the director's vision".

"None of this is very inspiring," Eszterhas grates. "I think it's so cynical. It winds up deflating and hurting. I've been writing scripts for 40 years; I've had 17 of them made. Basic Instinct wouldn't have been the movie it was if I hadn't taken Paul Verhoeven and Michael Douglas to the wall. My basic message is: believe in what you do, and put your heart and soul into it, and then be willing to fight for it."

In truth, if we're being as honest as Eszterhas would like us to be, for all his larger-than-life persona and souped-up truth-bearing, he is not what he once was in the industry. His last script to go before the cameras was Children of Glory, in 2006, a Hungarian-language tale of the country's 1956 uprising against the Soviets and the symbolic water polo match the nations played out at the Olympics in the same year. (An unlikely subject, perhaps, but Eszterhas has never been shy of reminding people he was born in a small Hungarian village, before his family emigrated to the US when he was a child.)

Before that, you have to go back to 1997, and two small-scale indies: the largely-approved-of autobiographical Telling Lies in America, about a Hungarian-born teenager in Cleveland (the Ohio city where Eszterhas spent his adolescence) mixed up in a payola racket with a local DJ; and Burn Hollywood Burn, a generally excoriated insider satire about a director's dismal experience on a big-budget action film.

If we're being even more honest, it's fair to say the writer seemed a bit of a dinosaur even then, just a few years after the queasily salacious Basic Instinct became a box-office smash; and a decade on from the early 80s one-two of Flashdance and Jagged Edge, which propelled Eszterhas into the Hollywood stratosphere to begin with.

Still, the fact is that Eszterhas remains a name, a draw, and a force to be reckoned with – even if he resembles a Jake LaMotta on the nightclub circuit rather than a fighting-weight Sugar Ray Robinson. With many more books published than films made in the last decade, Eszterhas can still talk a good game. (For example, the "17 scripts" he says he got made include Basic Instinct 2, for which he got paid but didn't write.) Famously aggressive throughout his star years, Eszterhas chose to take on even the mightiest, as shown in the legendary letter in which he accused the then-all-powerful CAA head Michael Ovitz of blackmail.

Inspiration is his stock-in-trade: he talks about the need to put your "heart and soul" into your work, to be willing to "fight for it, so you can look yourself in the mirror", so that "you know you fought the good fight". And deep down, he is a sensitive artist: "That's the nature of the beast: we are sensitive and we are frightened. Each time we go up on the high wire, you know you can fall off. Not only that, in Hollywood there are people who want to push you off. It all gets complicated."

Improbably, the man behind Sliver and Showgirls now comes off like the repository of decent, old-fashioned values, at least in writing terms. Eszterhas's hero remains Paddy Chayefsky, the combative writer of Marty and Network ("He essentially had the same attitude as me: didn't win 'em all but he fought for 'em all"), and he appears to still be burning with resentment towards the late Ken Russell, who he holds responsible for wrecking Chayefsky's career ("Russell broke his heart, what he did to Altered States").

Eszterhas's commitment to the written screenplay certainly means he's out of step with tentpole-oriented, superhero-obsessed Hollywood, and he acknowledges as such. "The people who run the studios are very different these days." The showbiz type of studio executive, he says, "who trusted their judgment, read something and said, let's do it" died out in the mid-90s – now, he says, the executives are younger, less experienced, less prepared to back themselves. "I happen to think they're all petrified for their jobs." Plus, "surrounded by accountants and businesspeople", studios "analyse everything. Scripts are analysed on the internet before they're even sold." Truly, the age of the maverick is over.

Eszterhas himself puts his creative radio silence down to a "horrendous" divorce (his current wife Naomi was married to a producer pal, Bill MacDonald, who dumped her for Sharon Stone, with whom Eszterhas rather tastelessly boasts repeatedly that he became very intimate some time earlier), assembling a new family, moving back to Cleveland, and getting over the cancer that rendered him unable to speak (and therefore unable to take meetings and script conferences) for two years. "The Showgirls and Jade defeats were papier-mache compared to that brick wall." Jade, for the uninitiated, was his last big Hollywood payday, a sleazy courtroom thriller that scored him a $2.5m fee for the outline. Directed by William Friedkin, it was a commercial disaster, and largely finished Eszterhas off as a major studio player.

But you can't keep someone as bullish as Eszterhas quiet for ever. He unexpectedly popped up in 2009 as Mel Gibson's writing partner on a script about the Maccabean revolt against the Romans in ancient Judea, a project initially seen as Gibson's attempt to rehabilitate himself after his 2006 antisemitic outburst at a traffic policeman.

However, their relationship imploded after Gibson rejected the script and Eszterhas went public with accusations of Gibson's undisguised "hatred of Jews". Eszterhas also released a tape of Gibson raging at him while a house guest.

Typically, he remains proud of the stance he took. "Had I not gone public with Mel, and not revealed any of this to the world, he would have just said, 'Oh, he wrote a terrible script.' And I didn't; I wrote a really good script, and I put my heart and soul into it."

There was an extra "personal" edge, says Eszterhas, as he had been appalled to discover in 1990 his father was a Nazi collaborator and was being investigated for war crimes (by coincidence, as it turned out, a development anticipated by the plot of his 1989 film Music Box). "Mel would have just fucked it over and that would have been the ball game. Because I loved the script … and that he could simply bury me as he tried to do on the Leno show, it was my way of fighting for my writing and my story and my vision.

"Mel truly needs help," he continues. "Something is very wrong. Unless something is done, unless someone intervenes, terrible things are going to happen, either to Mel or the people around him. I felt I had to do something about it. But the upshot is the script is in his drawer. He's probably still abusing people."

You wouldn't want to feel sorry for Eszterhas, and he wouldn't want it anyway, but it's safe to say there would be a groundswell of support if he managed to wrest The Maccabees away from Gibson and stick it to Gibson by getting it off the ground himself. It's not likely, though. "I'm still saddened about it, because I think it's one of the best things I ever wrote and there's no way to get it back." We can but hope.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion