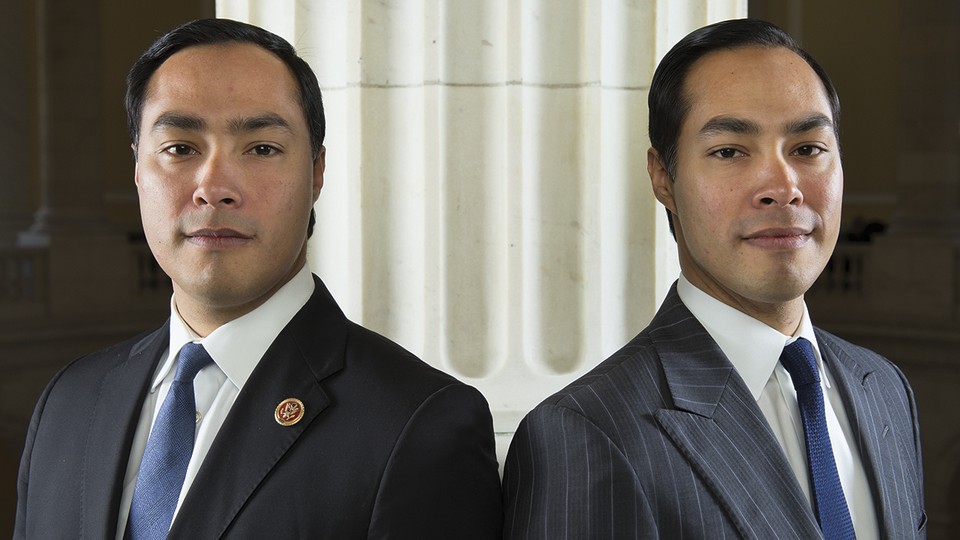

The Power of Two: Inside the Rise of the Castro Brothers

America has never seen a political team quite like the Castro brothers.

On a summer morning in 1999, Joaquin and Julián Castro pulled up in front of a double-wide trailer a few miles outside San Antonio. The twins, back home on break before their final year at Harvard Law School, had come to seek wisdom and advice from Lionel Sosa, a Republican political sage who ran the largest Hispanic advertising agency in America. (He was living in the trailer while his family's new home was being built nearby.) Politicos across the country knew Sosa as the ad man and consultant who'd helped Texas Republicans win substantial chunks of the Hispanic vote, and who'd led outreach efforts for Ronald Reagan's and George H.W. Bush's presidential campaigns. Soon, Sosa would be advising George W. Bush during his White House run.

Sosa didn't know the Castro brothers, but he did know not to expect right-wingers. Their mother, Rosie Castro, had been a fiery community organizer in San Antonio during the Chicano movement of the 1960s and '70s; after an unsuccessful run for city council in 1971, three years before Joaquin and Julián were born, she'd remained a political force in San Antonio, chairing the county chapter of La Raza Unida, a Chicano third party, and running other progressives' political campaigns. The twins had grown up tagging along to rallies, parades, and political functions. As Julián recalled in a college essay later published in an anthology called Writing for Change, political slogans "rang in my ears like war cries": "Viva La Raza!" "Black and Brown United!"

It was Rosie Castro who had reached out to Sosa; the two had met at a forum on the future of Latinos in America. Her boys, she told him, were planning to return to San Antonio and pursue some kind of public service after they graduated. Would Sosa mind speaking with them?

Joaquin and Julián sat down in the trailer, Sosa says, and began to pepper him with questions: Where do you think San Antonio is headed? Who should we know? After a while, Sosa turned the tables and asked them one: What did they see in their futures? The way Sosa remembers it, the brothers broke out into big grins and told him, in unison, "We're going to be mayor of San Antonio."

"We're going to be mayor?" Sosa said. "Which one?"

"One of us will," said one of the brothers.

Sosa, who's now semiretired, can recount little else about the conversation that day, or what counsel he gave the Castros. But their joint reply, he says, stuck with him: "That's the one thing that got seared into my mind. They knew what they wanted in life." And they knew that they wanted to attain it together.

Rosie Castro's Chicano activism inspired her sons, though they took a more centrist path. (Rick Kern/Getty Images for HBO)

I RECENTLY SPENT two months in the Castros' orbit, from just after Election Day to mid-January, interviewing and observing them in Washington and San Antonio, together and separately. They can be salty-tongued, charming, funny, and withering, especially when it comes to other politicians. Former campaign staffers attest to their fiery tendencies—particularly on the other's behalf. "Any mistake on Joaquin's campaign, and you are messing with Julián," says Christian Archer, who's managed races for both brothers. The same goes for Julián's campaigns, when Archer says Joaquin has been "as aggressive as I've ever seen him," demanding fundraising totals or email analytics.

But I also found the brothers exceedingly careful, even for political wunderkinds on the rise, to cloak their candid sides. In almost every conversation we had, they danced back and forth between being on the record and off the record—sometimes from one sentence to the next. By the end of our time together, I half-expected them to begin their lunch orders by asking the waiter, "Can this be on background?"

Maybe their reticence shouldn't be surprising; after all, they've now got a lot to lose. Fifteen years after visiting Sosa, the Castro brothers' political horizons have broadened well beyond San Antonio. Joaquin, after a decade in the Texas House, won a seat in Congress in 2012 and soon became a fixture on Sunday talk shows, a go-to surrogate for President Obama's immigration and economic policies. But the spotlight shines most intensely on Julián, the San Antonio mayor who vaulted into the national consciousness with his keynote address—the first by a Latino—at the 2012 Democratic National Convention. Last year, when Julián left the mayor's job to join Obama's Cabinet as Housing and Urban Development secretary, the move stirred widespread speculation that he was being positioned as a potential 2016 vice presidential pick for likely nominee Hillary Clinton. Barring that, Texas Democrats have long envisioned Julián—or maybe Joaquin?—as the state's first Latino governor. Or as a U.S. senator. Or maybe both.

"The whole idea that they could be governor, senator, vice president, president—it excites people," Rosie Castro told me. "Everybody is waiting for the first Latino governor of Texas. Everybody is waiting for that first Latino president or vice president." And no two Democrats are better placed to realize such expectations than Rosie's sons. The Republican Party, despite its struggles to attract Latino voters, has more Latino politicians with national profiles and prospects—Sens. Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, for starters, along with Govs. Susana Martinez and Brian Sandoval. For Democrats, at least for the time being, such hopes hang mostly on the Castro brothers.

They are, it seems, the chosen ones: whip-smart, telegenic politicians who've arrived in the right political place at the right political time. Their life story has a fairy-tale quality that reporters and mythmakers can't resist: Born on Mexican Independence Day. Raised by a grandmother who immigrated to the United States as an orphan with a fourth-grade education and a mother who agitated, organized, and was twice jailed for civil disobedience in the cause of giving the next generation—her sons, in particular—opportunities she never had. Worked their way up from the barrios to Stanford, then Harvard, then one of the country's most prestigious law firms. Elected to political offices before age 30. Washington darlings at 40. Even if Julián never becomes vice president or president—even if neither brother ever wins a statewide office in Texas—theirs is already so quintessential an American success story that Eva Longoria, best known for her role in Desperate Housewives, has sold ABC on a political and family drama series she's producing based on the Castros. Working title: Pair of Aces.

The brothers understand the power and usefulness of the larger-than-life stories that have grown up around them. But there is at least one that they're eager to shoot down: the "we're going to be mayor" anecdote that Lionel Sosa tells. "That's not true," Julián Castro says flatly. "I was never so arrogant to say that I would someday be mayor. Maybe I said, 'Oh, I'm thinking about running for city council.' " Sure, he says, "I certainly think that's [Sosa's] recollection. But I seriously, seriously doubt that." It's the type of fable, he says, that "people develop in their mind, and it sounds good. But it's the stuff of embellishment."

Then again, Julián may be forgetting something himself. In 1997, two years before the brothers met with Sosa, they had been profiled in a San Antonio newspaper as they headed off to Harvard Law (headline: "Double the Talent, Twice the Ambition"), and Julián had spoken about even higher goals than the one Sosa recalls: "We do not consider the office of governor or [U.S.] senator an impossibility," he told the reporter.

Today, the Castro brothers take pains to be humble. But they've always had ambition in abundance. Their precipitous rise has been the result of lofty aspirations, careful calculation, ferocious loyalty, and deep political pragmatism—qualities the brothers have long shared and mutually cultivated. "Growing up, I think what's helped my brother and I is, we were so competitive with each other," says Joaquin. "Because we're in the same field, it's allowed us to talk almost daily. Lets you identify strengths and weaknesses in your arguments." Colin Strother, a Texas political consultant who has worked on Joaquin's campaigns, puts it more bluntly. "You see this synergy with Bill and Hillary," he told me. "Steel sharpens steel."

EVEN FOR TWINS, Julián and Joaquin were unusually tight-knit from their earliest days. They played the same sports, studied the same subjects, and, in middle school, even dated girls with almost identical names: Veronica Gonzalez and Veronica Gonzales. They communicated with each other in often-unspoken ways that frequently were beyond the ken of everyone around them.

They never truly grew apart. "It is one of the most intense relationships that two people could share," Archer says. Even after marrying, starting families, and following their different political paths in San Antonio, Austin, and now Washington, they remain incredibly close. (Julián wed Erica Lira, an elementary school teacher, in 2007; they have a 5-year-old daughter and a son who was born in December. Joaquin married Anna Flores, who works for a San Antonio tech company, in 2013; they have a 1-year-old daughter.) "They're not easy people to get to know," says their longtime friend Diego Bernal, who served on the city council when Julián was mayor. As children, they "were the whole world to each other," says their mother, Rosie. It was "hard to penetrate that."

Neither of the brothers is naturally outgoing; they've had to learn to master the glad-handing, baby-kissing, money-asking skills required of politicians. Julián likes to say that in high school he would often talk to two or three people the entire day—and one of them was his brother. "I was not the life of the party," as he puts it. "Still am not." Joaquin was always the slightly more sociable one: He'd make friends, who would, in turn, become Julián's friends as well. "Julián has always been more introspective," Rosie says. "If I had let him, he'd stay home, hang around the house. Joaquin, too, but he also likes an escape, being out in the world."

Spend enough time around them, talk to enough of their friends, and you pick up small differences: Julián speaks more softly, in a slightly deeper voice; Joaquin's face is slightly thicker (though the clue I used, when both brothers were present, was the FitBit that Joaquin wears). But the twins seem to share almost everything else—including the fact that they have perplexing tastes in music. As a teenager, Julián once took a CD of theme songs to TV shows like The Golden Girls and Cheers to a New Year's Eve celebration, and he's been known to jam to Kenny Rogers and Barry Manilow. Joaquin's tastes range from Joan Baez to Taylor Swift, with a particular affinity for bands (Matchbox 20, Counting Crows) from the late '90s, which he once called "a renaissance in music."

In part, the brothers grew inseparable because they helped to raise each other. Rosie was the opposite of a helicopter mom; she was stretched thin, between work and politics and single-mothering, but she was also determined to push "the guys," as she calls them, out into the world. Her immigrant mother, Victoria, made $8 a day as a maid, cook, and babysitter on the north side of San Antonio; and while her mother worked, Rosie's guardian held tight to her as a child, forbidding her to even walk next door to play with the neighbors. (Rosie did sometimes accompany her mother on her three-bus commute to work, however, and recalls spending time picking ticks off the dogs that belonged to one of her mother's employers.) Rosie encouraged Joaquin and Julián to enjoy the kind of freedom she never had as a child; they both still remember, the summer when they were 9, riding the bus downtown by themselves to see The Karate Kid at a sketchy theater no fewer than five times.

Their family wasn't all that far removed from the poverty of Rosie's youth, especially after Rosie and the twins' father, a Chicano activist and math teacher named Jesse Guzman, separated in 1983 (they never married). Joaquin and Julián were 8 when their dad left. They moved with Rosie and their grandmother to a modest house near one of Rosie's cousins. The Castros went without a car for years, and for a while, when the boys were in high school, had to rely on money from friends after Rosie was laid off.

The boys still saw their father pretty regularly on weekends and took summer fishing trips to Garner State Park. When I spoke to Guzman in December at a west-side Mexican joint called Laguna Jalisco, he talked about his pride in the twins—"I'm very humbled by everything they do"—and recalled one big difference he noticed between them. "Julián had a graceful way of casting his line out there. Have you read A River Runs Through It? Reminds me of that book. Julián brought all his tackle and was very organized. But Joaquin didn't like fishing."

Julián and Joaquin pushed each other to excel. They studied Japanese (Julián) and German (Joaquin) at a language-intensive junior high school in the inner city (a childhood friend describes it as a "maximum-security middle school"). They enrolled in night classes and summer school so they could finish high school a year early. "Part of the reason that we were so looking toward the future, toward success, is because we had grown up of modest means, and we were always worried about falling back," Joaquin says. "You want to be sure—I'm going to be OK, I'm going to be OK."

"It is one of the most intense relationships two people could share," says a top Castro adviser.

The elation that Joaquin and Julián felt upon opening their acceptance letters to Stanford in the spring of 1992 was replaced by sadness and raw nerves on the morning of Sept. 23—even now, Julián recalls the exact date—when they waved good-bye to their parents and a crowd of friends and well-wishers who'd come to see them off at the San Antonio airport. Their father, as Julián tells it, must have purchased "the cheapest ticket on Southwest Airlines he could find"; the flight connected twice, in El Paso and San Diego, before it reached San Francisco. "It was the first time we'd been away from our family," Julián recalled last year in a talk at Notre Dame. "We cried halfway to El Paso on the plane, sitting next to each other."

WHEN LUIS FRAGA gazed out on the roomful of students in his urban politics course, he noticed something that gave him a start: two look-alike brothers seated dead center in his classroom. Before long, Fraga, the only Latino political scientist on Stanford's campus at the time, came to know Joaquin and Julián Castro as two of the savviest students he'd ever taught. "It was immediately apparent to me," Fraga says, "that they had an understanding of politics that was deeper than any other college sophomores I'd come across."

The brothers matriculated in Palo Alto as the first high-tech boom was beginning. Other Stanford students at the time included Peter Thiel, later the iconoclastic founder of PayPal, and David Sacks, who would go on to sell his company, Yammer, for $1.2 billion and own the most expensive house in San Francisco. Silicon Valley's high-rolling economy and entrepreneurial ethos was a far cry from life on the west side of San Antonio, and the brothers felt some culture shock—plus a bit of defensiveness about where they came from. "I had a chip on my shoulder about San Antonio," Julián says. The brothers doubled down on their hometown pride, urging their entrepreneurial classmates to "consider San Antonio" after graduation. But they also learned new ways to think about solving societal problems, Fraga says. "It was an atmosphere of creativity and thinking about technology as a potential source of solutions for all kinds of things. That made a big impression on Julián."

In their junior year, both brothers ran for the student senate on the left-leaning People's Platform—and another mythmaking moment was born. There were 10 seats open, in a multicandidate race. Joaquin and Julián created separate campaign fliers, but posted them in the same strategic spots around campus—bathroom stalls. (Fraga, who became their senior adviser and then a friend, still calls them the "Stall Twins.") On election day, the brothers earned exactly the same number of votes—811—on their way to being the top vote-getters. A front-page story in The Stanford Daily posed the brothers sitting back-to-back in the university's historic Memorial Court. Reading the article, you can practically see them rolling their eyes at the reporter's "What's it like to be a twin?" questions. "We don't particularly subscribe to twins having ESP," Julián is quoted as saying. "We get asked that question millions of times."

Some daylight began to appear between the brothers at Stanford. While they mostly took the same classes, they chose not to room together. The summer before their junior year, they were separated for months when Julián went to Washington as an intern in the Clinton White House. In the fall of their senior year, when Joaquin was hired as a resident assistant in his dormitory, he felt, for the first time, the weight of following in his brother's footsteps. (Julián had been an R.A. the year before.) "I don't think I did as well in the job," Joaquin says, "because I felt like I could [only] get the job because he had done it."

In politics, too, it was becoming clear that Julián—the elder brother by one minute—would go first. By their third year at Harvard Law, Julián had already decided to run for the San Antonio City Council. (Hence the visit to Lionel Sosa, who knew San Antonio politics as well as anyone.) During their final year, the brothers launched the campaign from Cambridge. They called neighborhood-association leaders, wrote letters to local businesspeople, and flew home on weekends whenever they could to meet and greet prospective voters at community gatherings and garage sales. (Joaquin, who doesn't play golf, still owns an ancient Ben Hogan 3-wood he bought at one of the sales for $5.) Just before graduation, their law-school classmates threw Julián his first fundraiser. The following May, three decades after Rosie lost her own campaign at age 23, Julián became the youngest council member in San Antonio history at 26.

It wasn't long before Joaquin followed suit—but on a different track. Both brothers had been hired out of Harvard by the white-shoe law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld (Julián's City Council gig was not a full-time job), but neither had learned to love corporate law, to say the least. Years earlier, local activists had tried unsuccessfully to draft Rosie into challenging a Democratic incumbent in the state House—a longtime pol who, according to Rosie, had developed a do-nothing reputation. Now Joaquin decided to take him on. Though he says he "agonized" over abandoning his six-figure salary, he relished the idea of going to Austin to work on "big-ticket issues" such as higher education and health care. He also wanted to escape his brother's shadow and strike out, at least somewhat, on his own. "He was now on council," Joaquin says, "and I wanted to do something different."

With Rosie and Julián helping to run his campaign, Joaquin dispatched the Democratic incumbent easily, winning the primary with 64 percent of the vote. In the general election, he held off a Republican who'd been generously funded by some of the biggest Anglo donors in the state. The Castro family celebrated another victory, but Joaquin's timing could hardly have been worse; 2002 was also the year when Republicans won their first majority in the Texas House since Reconstruction. "I came in," Joaquin says, "when it all went to shit." So much for pushing "big-ticket" ideas. That would become his brother's forte instead. But not until Julián had experienced, at the tender age of 30, his first major political setback.

In 2012, Joaquin (right) introduced his keynote-speaking brother to the Democratic Convention—and to the country. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)JU-LI-ÃN! Ju-li-án! Ju-li-án!" The chant rose up in the San Antonio City Council's chambers on April 4, 2002. The council was voting that evening on $52 million worth of special tax breaks for the developers of a new golf resort and upscale-housing project called PGA Village. Competing factions had filled the chamber seats, wearing stickers that said "PGA No!" or "PGA Yes!" A few months earlier, Julián had quit his job at Akin Gump. (The firm's lawyers had drafted the developers' contract.) It was the highest-profile issue of his early days in office, and he was hell-bent on making the most of it. Julián seized the spotlight at the hearing, sharply interrogating the developers' representatives over their claims about the project's environmental impact (low, they said) and economic potential for the city (sky high, of course). The "PGA No!" crowd ate it up, but Julián's performance went for naught: Only one of the 10 other council members voted with him to block the deal.

The loss did nothing to dim Julián's enthusiasm for city government. Despite the meager pay—$20 a meeting—he relished the nonpartisan world of council politics. He didn't mind that constituents would call at all hours to complain about barking dogs or their neighbors' unkempt lawns. He was happy to attend your neighborhood-association meeting next Wednesday at 7 p.m. He even lent a patient ear to the cast of gadflies who regularly came to council meetings to air their grievances for the allotted three minutes each. Jaime Castillo, a San Antonio Express-News columnist who would later become Julián's deputy chief of staff, took notice of the polite attention the young council member gave the complainers. His attitude, according to Castillo, was: "These people are here to speak to the body. By God, they're going to get their three minutes, and I'm going to listen."

But Julián couldn't serve on the council forever. At the time, San Antonio had among the strictest term limits in the country; council members couldn't serve more than two two-year stints. (The rules have since been loosened.) In 2004, with the expiration of his second term looming, Julián decided to run for mayor.

Julián Castro was known to San Antonio voters, if he was known at all, for three things: his youth, his family, and his loud opposition to PGA Village. All three would be used against him in what became a bruising campaign—one that would ultimately lead him to dramatically reinvent his political identity.

His chief opponent, a retired appellate judge named Phil Hardberger, was backed by the city's business establishment, which was highly suspicious of the young Castro. After two council members were arrested on bribery charges, Hardberger used it to turn Julián's inexperience against him; the council, he argued, needed a wiser old head to clean up the mess. Hardberger's campaign also managed to drum up the closest thing to a political scandal in the Castro brothers' career—an affair dubbed "Twingate" in the local press. In April 2005, it seems, with the mayoral campaign in full swing, Julián and Joaquin were both scheduled to ride and wave atop the city council barge in the annual River Parade. At the last minute, though, Julián says he decided to attend a neighborhood-association meeting instead. Whatever the reason, Joaquin ended up riding on the barge alone. Hardberger's campaign managed to turn the incident into a story of deception and political cunning, accusing the Castros of pulling a fast one on the denizens of San Antonio by swapping one brother for another in the parade.

Whether or not Twingate doomed him, Julián lost. The defeat hit him hard—the first time in his life that he'd truly tasted failure. "Elections are so determinative in that way," he says. "There is no, 'You wanted an A+ but you got an A,' or 'You wanted 100 percent but you got a 93.' The people either accepted or rejected you." But this rejection would become a major turning point in the story of the Castro brothers.

A few months later, around the time of the brothers' 31st birthdays, Joaquin dropped by Julián's house with a present. This wasn't typical: As close as they are, the Castro brothers are far from expressive. They only occasionally exchange birthday gifts, they've never been big on "I love you's," and Julián told me that he could remember hugging his brother only five or six times in their 40 years. Joaquin's gift was a small volume titled How to Be President. Part spoof, part dummy's-guide-to, the book purported to answer the fundamental questions about life as commander in chief: Where's the bathroom? When do you get to fly on Air Force One? How do you order pizza delivery to the Oval Office?

Joaquin meant it partly as a joke, he says—not a prediction that his brother would actually end up in the White House. At the same time, there was a message in the gift, which Julián says he understood as: "I still think you can do whatever you want."

The brothers, characteristically enough, were already working on that. Not long after the election, Christian Archer, who'd run Hardberger's campaign, spotted the Castros eating lunch at their favorite Mexican restaurant, Rosario's. He hadn't seen them since Julián lost, and he tried to make himself inconspicuous in hopes of avoiding them. They spotted him anyway. "I give them a pleasant wave," Archer recalls, "and Julián jumps up and runs over and grabs me and says, 'Would you mind having lunch with Joaquin and I?' "

The three men sat and talked for two hours. The Castros weren't bitter; they were curious. What did we do wrong? they wanted to know. How did you choose this message, that line of attack? "I came away from that with the utmost respect," Archer says. "That took some real nerve and moxie to say, 'Help us understand this.' "

Julián was convinced he couldn't mount a successful comeback if the business establishment continued to distrust him. For the next four years, when he wasn't working personal-injury cases for the new Law Offices of Julián Castro—Joaquin joined the firm, of course—he worked on changing that image completely. Julián broke bread regularly with business leaders, and, when the time came for his next shot at the mayor's office, he hired Archer and the rest of Hardberger's '05 team to run his campaign. (Because of term limits, Hardberger couldn't run again.) Julián ran as an ally of the real-estate developers and bankers and tech entrepreneurs, and a champion of public-private partnerships as the way to improve the schools and attract new jobs. And he cruised to victory, winning 56 percent of the vote in a five-candidate race. One year later, when The New York Times Magazine profiled Julián as the future Barack Obama—the Latino who'd break America's next racial barrier to the presidency—it dubbed him the "Post-Hispanic Hispanic Politician." Julián bristled a little at the moniker, but even so: mission accomplished.

Mayor Castro governed as he'd campaigned. He opened a public-private college-prep center called Café College, and a similar site for aspiring entrepreneurs. He embraced the use of tax abatements to lure large employers to the city. He led a public-private crusade to revitalize San Antonio's urban core. And when he embarked on his most ambitious effort, a citywide expansion of prekindergarten education called "Pre-K for SA," he persuaded the two biggest CEOs in San Antonio—Charles Butt, founder of the HEB grocery chain, and Joe Robles, head of the U.S. Automobile Association—to spearhead the campaign to pass a $30 million sales-tax increase to get it rolling.

By the time the voters embraced Pre-K for SA in November 2012, the Castro brothers had two feet in Washington. Joaquin had found his ticket out of the sad minority in the Texas House, winning his first congressional election—only to join another new Democratic minority in the U.S. House. Julián had delivered his Democratic Convention keynote that summer, leading to all kinds of buzz and interview requests. Shortly after the election, Obama and senior adviser Valerie Jarrett met with Julián to gauge his interest in joining the Cabinet; they didn't specify which department, but it was clearly Transportation, which didn't appeal to him. He said no, but the idea of taking a post in D.C. had been planted.

THIS PAST SPRING, President Obama and Mayor Castro were featured speakers at the LBJ Presidential Library's 50th anniversary celebration in Austin. Backstage, Julián recalls, the president sidled up to him. "He said, 'I've been meaning to give you a call. Let's talk soon.' Probably a week later, he called, and we had [a] conversation about possibly joining the administration." This time, the offer was to run HUD—a department closer to Julián's heart, given his urban-development efforts in San Antonio. The brothers also understood perfectly well that there was no chance that the mayor of San Antonio would be tapped as vice president. But a young Latino Cabinet member with Clinton-style moderate politics and a ton of great press? Maybe.

It wasn't an automatic call, though. Leaving Texas would take Julián off the path to the governor's office that so many expected him to follow when his fourth two-year term as mayor (that was now the term limit) ended in 2017. The timing had once sounded plausible. Political pundits and optimistic Democrats had long expected favorable demographic trends—a whole lot of young people of color becoming voters, that is—to make statewide elections winnable by then, especially for the right candidate. (And if there were ever a "right" Democratic candidate, most agreed, it was Julián Castro.) But with the much-hyped gubernatorial bid of state Sen. Wendy Davis headed toward a historic rout—she lost by more than 20 percentage points—the revival of Texas Democrats had begun to look like a far more distant prospect.

When Julián asked Rosie what she thought about Obama's HUD offer, she said, "This is the second time he asks you. He's not gonna ask you again. But is this something you want to do?" He wasn't sure. Some advisers thought HUD was a dead-end job. Others pointed out that Julián would be joining the administration during its lame-duck phase—not the optimal time for launching ambitious projects that could boost his national profile. It would be, said Evan Smith, CEO of The Texas Tribune, "like John Stamos joining ER in the 13th season—show's over, man."

When he took the job anyway, it was a sure sign that the Castro brothers had decided that Texas wouldn't be competitive for Democrats anytime soon. It also appeared to be a bet that Julián's presence in Washington, and his new role, would make him more appealing to Hillary Clinton if she became the Democratic nominee.

Still, the brothers know that vice president is a long shot—especially because, they insist, the rumors about their cozy links to Bill and Hillary are patently absurd. Their relationship with the Clintons is friendly, they say, but far from intimate. Julián's only interaction with President Clinton during his White House internship was a photo session. The brothers endorsed Hillary over Obama in 2008—at the behest, they say, of old Clinton pal José Villarreal, a family friend and the partner who'd hired the twins at Akin Gump. Bill Clinton always remembers the Castros' endorsement and thanks them when he sees them, Julián says, but that's only been on "a handful of occasions." The brothers have introduced the former president at fundraisers in California and Texas, Julián notes, and "I've spoken with Hillary Clinton twice"—once at an event at the University of Southern California in 2013, and once at a 2014 benefit for the Bronx Children's Museum, which Justice Sonia Sotomayor invited them to. Last August, Julián dined with Bill Clinton at the couple's home in Washington. "A lot of people try and brag about long, close relationships with the Clintons," Julián says. "We don't have a long, close relationship." But, he adds, "I think we're on the same page about a lot of stuff."

While Julián thinks nationally, his brother's mind keeps drifting back to Texas. In December, Joaquin Castro and I sat at the top of the 750-foot-high Tower of the Americas, gazing out on San Antonio, chatting about the brothers' past and possible futures, Texas politics, and the 2016 presidential race. (Joaquin ranks Mike Huckabee as the most natural politician of the potential GOP field, saying he could "walk away" with the nomination "if he wasn't so odd.") The congressman, fresh off an easy reelection, pointed out some notable spots: the brothers' old neighborhood, the spire at Our Lady of the Lake University on the west side, the place nearby where Woody Harrelson's father killed a federal judge by the name of "Maximum John" Wood Jr. Over soup, salad, and iced tea—both brothers' drink of choice—Joaquin talked enthusiastically about his new project to resuscitate Texas Democrats.

"I'm always thinking about politics," he says. "What is going on here? What's missing here?" In Texas, what's missing is pretty obvious on one level: Democratic voters. Despite the advent of Battleground Texas, a well-funded effort led by former Obama campaign brass designed to register and turn out new voters, Joaquin says there's only one way to view the 2014 election: "We got our ass kicked." The party's situation just keeps growing more dire, he says; between 2008 and 2012, Republicans went from occupying 2,400 local elected offices in Texas to owning 3,400. "We never learned how to come back," he says. "We still haven't figured out the formula in Texas."

Joaquin doesn't want to supplant Battleground Texas, he explains, but to complement it with some well-funded, year-round hardball politics. The Legislature meets every two years for 140 days, and every session Republicans cut more deeply into funding for social services, he says—yet they're never held accountable for it, come election time. "For example, a few years ago they wanted to cut funding for nursing homes," he says. "I mean, that's perfect! You could run that on the radio all day. You need to sear it in people's brains, so the next time they go, 'Hey, I remember—these are the guys who wanted to cut your nursing-home funding!' "

Another key, he argues, is expanding the usual targets for a political party. "What campaigns do is, they target likely voters, consistent voters, right?" he says. "You need an organization that completely flips the script. I don't want to talk to likely voters; I want to talk to people that are completely, or almost completely, disengaged."

His road map for Texas Democrats is still in the early stages, but if he had to put a price tag on it, he'd estimate upwards of $50 million. Joaquin had meetings scheduled in January with potential donors in hopes of getting things rolling. (He would not say who those funders might be.) When I ask how he's planning to run a Democratic-renewal project in Texas while working 12-hour days in Congress, raising his young daughter, and comanaging his brother's political future, he admits that he sometimes thinks fondly about leaving his minority caucus in Congress. "Some of the things I want to do and be involved with in bringing Texas along, it would be easier not to be an elected official," he says. "Specifically, not to be a congressman."

He knows, of course, that nothing would benefit his Texas project like a brother on the national Democratic ticket; that would make raising $50 million a snap. "If he ascends, that helps me too," Joaquin says. It works both ways, of course: If Joaquin makes any notable headway with his Texas project over the next year and a half, the prospect of putting a Texan on the Democratic ballot would make more strategic sense for the party's presidential nominee.

While the brothers still harbor blue-sky ambitions, they're also realists. They know that in the likely event Julián doesn't get the VP nod, their political path forward suddenly vanishes, at least unless Texas someday becomes competitive again. "Sure, I've thought about it," Julián says of having nowhere to go when his HUD appointment expires. "It's very possible. I've thought about going back to Texas and writing, and perhaps practicing law." He's also open, he says, to "sticking around somewhere in the Cabinet" if Clinton, or another Democrat, becomes the next president. "Most days, I'm excited about public service, but there's some days, like in any profession—there's the down days when I think about just going back home and having more freedom, you know? So we'll see what happens. The good thing is, I'm gonna be 42 when that day comes. Still a lot of time left."

But there is also a sense of urgency to the brothers' political plans. When we met for lunch in December at one of his favorite Mexican restaurants in San Antonio, Julián said he felt increasingly optimistic that he made the right move in going to Washington. "Joaquin and I were talking a couple of months ago," he said, "and I told him, 'I feel like the world is coming toward us in a positive way. More now in our lives than it ever will again.' "

Andy Kroll is a Washington-based reporter for Mother Jones.