It seems somehow fitting, both as this publication’s resident art critic and as a half-Spaniard, that the first exhibition I’ve been able to visit and write about since COVID-19 lockdowns explores the phenomenon of Americans traveling to Spain: something I’ve been prevented from doing for nearly a year now.

Whether you’re primarily interested in simply looking at beautiful works of art, or if you care to wade into the somewhat unexplored waters of Spain’s influence on American art of the 19th and early 20th centuries, “Americans in Spain: Painting and Travel, 1820-1920,” which opened at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk this past weekend, and will later head to the Milwaukee Art Museum this summer, is a terrific show. The exhibition proved to be an all-too-brief reunion with something that has been denied to me for lo these many months of lockdowns and travel bans, and which I very much need to feel completely myself.

Despite not only the country’s active support of the American Revolution but also the intertwining of Spanish and American history in territories formerly ruled by the Spanish Crown that subsequently became part of the United States, due in part to the relative isolation of the Iberian Peninsula and a comparatively cautious embrace of industrialization, at the beginning of the 19th century Spain was something of a mystery to most Americans.

The European “Grand Tour” many visitors have taken usually bypassed Spain entirely, by beginning in London or Paris, and continuing through France, Germany, the Low Countries, Switzerland, and Italy, where geographic contiguity and a surfeit of guidebooks, transportation options, and tourist accommodations made travel comparatively easier. These practical factors, along with an aversion to garlic and Catholicism, kept all but the most intrepid of early 19th-century American travelers from visiting Spain for pleasure.

With the publication of books about Spain such as Washington Irving’s “Tales of the Alhambra” (1832), however, in which American writers combined fictional narrative and personal travelogue to create a sense of the exotic, American interest in all things Spanish began to increase.

Although a number of these works contained observations based on misperceptions of Spanish history and culture, they nevertheless fired the imaginations not only of American tourists but also of 19th-century American artists. During most of the 19th century, there was a relative dearth of Spanish art in the United States, and for both the budding art student and the accomplished professional, the only way to see works by Spanish Old Masters outside of engravings or early photographs was to cross the Atlantic to visit Spain herself.

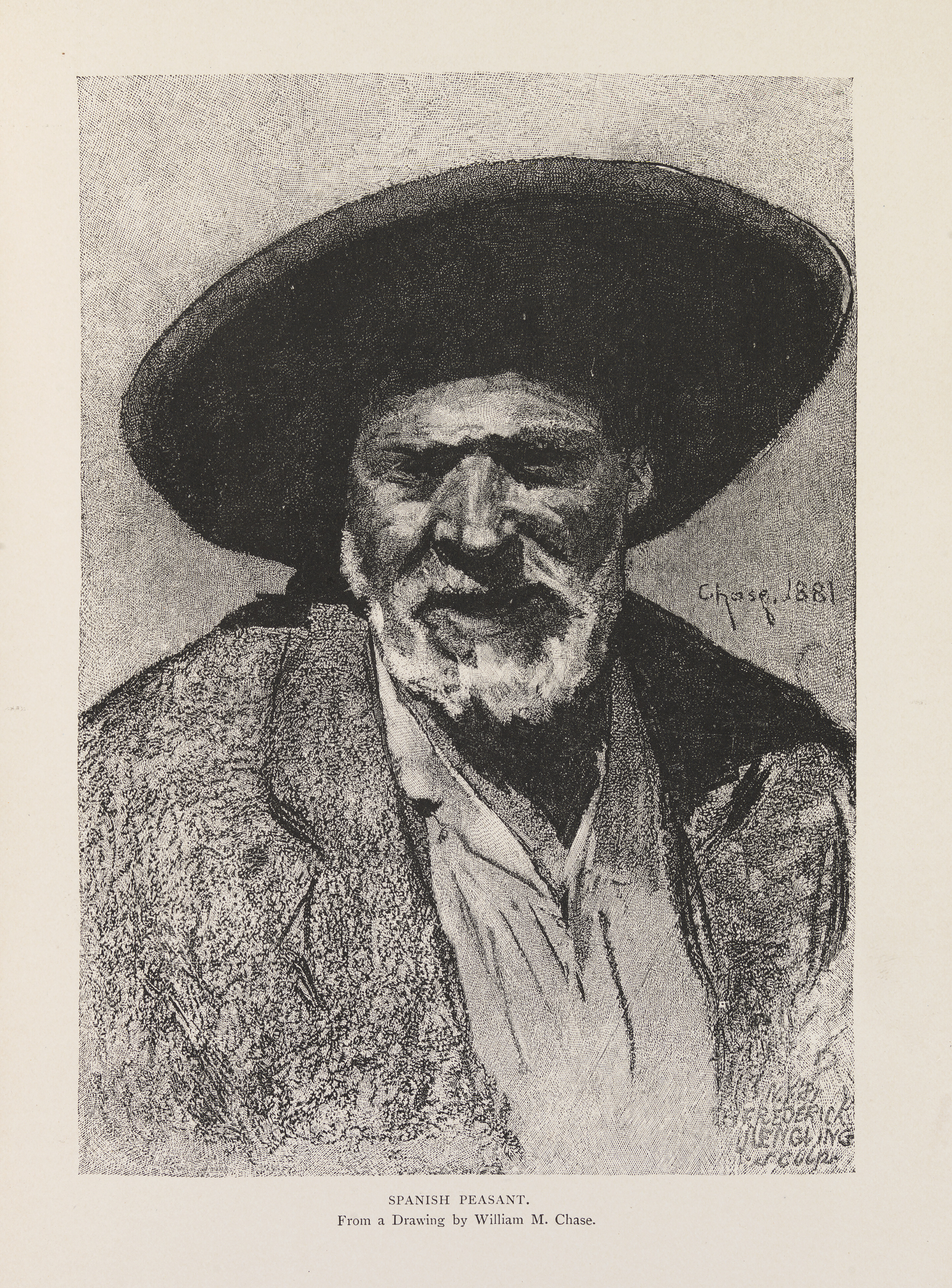

Many of the Americans who painted in Spain during the period covered by this exhibition are extremely important figures in the history of American art indeed, and their work comprises the majority of objects on display: Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), Childe Hassam (1859-1935), Robert Henri (1865-1929), and of course, John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), who has often been referred to as “the American Velázquez” (if you disagree, I don’t care to know you).

Other American artists visited Spain as well, and while some are less well-known today than they were in their time, the show does a good job in balancing both the household names and the less prominent ones so visitors can more fully explore the thematic and stylistic connections between these artists.

The exhibition design aids this. Sections examining specific topics are differentiated from one another by coordinated bright colors on the walls. Plenty of room is provided for multiple groups of visitors to circulate, or for a single visitor to stand back or have a seat on a convenient bench. During my visit, however, the maximum number of visitors in the exhibition space at any one time was capped at 20 people.

The exhibition explores several themes, such as the perception of the “otherness” of Spain as compared to the rest of Europe and the United States at the time, and the American fascination with bullfighting and flamenco music and dance. The importance of studying and copying Old Masters as part of an artist’s education during the 19th century is particularly well-documented in the show, with copies of Spanish Old Master paintings by many important artists, as well as a number of actual Spanish Old Masters from El Greco to Zurbarán for comparison.

The presence of works from a selection of Spanish artists such as Mariano Fortuny (1838-1874), Joaquín Sorolla (1863-1923), and Ignacio Zuloaga (1870-1945) who were contemporaries and in some cases friends of the American artists featured in the show allows the visitor to see how American artists could observe what their peers were doing, but still come up with their own, original interpretations of similar subjects.

For many, perhaps the most startling art in the exhibition will be a group of three works by American Impressionist Mary Cassatt, painted while she was living in Seville. Cassatt is, of course, most famous for her later pastel-colored images of women and children, heavily influenced by the French Impressionists and by Japanese prints.

In this show, however, you will find no hint of either in works such as “After the Bullfight” (1873), depicting a bullfighter in profile lighting a cigarette, or “Spanish Girl Leaning on a Windowsill” (1872), in which a young woman in traditional dress boldly looks out at the viewer.

With these Spanish-themed pictures — dominated by jewel tones, dark backgrounds, and thick impasto — the figures are executed with both a feeling of mass and a deliberate directness, with none of the vaguely pensive demeanors or unusual points of perspective Cassatt explores in her better-known work. Indeed, unless you read the accompanying placards, chances are you wouldn’t even guess they were Cassatt’s work at all.

While there are many outstanding pieces in the exhibition, I was most affected by William Merritt Chase’s “The Outskirts of Madrid” (1882), which I’d never seen before. This is a rather bleak picture, despite the blinding sunshine, what with the garbage, crumbling buildings, industrial pollution, and images of the poor living on the fringes of society.

In spite of its arresting power, and the bravery of the artist in tackling an unpleasant subject and in creating an image primarily made up of beige and blue fields, the painting isn’t particularly prominently displayed, so the visitor will need to hunt for it a bit. In the Norfolk incarnation of the show, it’s tucked into a corner opposite two monumental, glamorous images of the celebrated dancer Carmen Dauset Moreno (1868-1910), better known by her professional name, “La Carmencita.” She was painted in New York by both Chase and Sargent in 1890, when she was the toast of Broadway. It would be difficult to think of a more profound contrast between subjects.

As I couldn’t help commenting aloud to an exhibition companion while standing in front of the painting, Chase really “got” Spain in this picture, particularly given that he painted an unflattering, dare one say superficially ugly, image of a Madrid that few tourists ever saw. The urchin grinning uncomfortably at the viewer obviously harkens back to Murillo’s treatment of these types of figures, which is natural enough given the American fascination with Murillo at the time it was painted.

Yet this isn’t simply an evocation of one Spanish Old Master working in a very particular time and context. It carries a much broader understanding on Chase’s part of the sense of vast, empty space that one finds when traveling across much of Spain, and the awkward characters captured on canvas for centuries by artists as diverse as Ribera, Velázquez, and Goya, and later by Zuloaga, Nonell, and the young Picasso.

For all of its “Spanishness,” which is all the more surprising given that the artist was an American, there’s also something deeply, universally spiritual about this picture that, at least to a secular, materialistic society, might seem counterintuitive or even macabre. Humility and poverty are always a surer path to God than self-actualization or achieving influencer status, and the divine is often to be encountered more readily in out-of-the-way places such as deserts, where there are fewer material distractions and comforts. So, while I can’t say this is a Spain that I know personally, I can say this is a Spain that I recognize.

In having that moment of recognition, of course, my take on this work, and indeed, on the entire exhibition, was ultimately a more personal one than I normally allow myself to indulge in when reviewing a show. As of this writing, I’ve missed two trips to Spain, and will almost certainly miss a third in a few months, courtesy of the present pandemic.

Seeing this wealth of art, both American and Spanish, was a joy, both in being able to go to a museum exhibition again, as well as in seeing familiar names, places, and subjects on canvas. At the same time, it also brought painfully home to me what I miss about Spain.

I miss the unexpected sensory stimuli that occur without warning: staccato voices and clacking heels passing by sidewalks paved with tiles; basking in an unexpected patch of bright sun piercing through a dark, tangled maze of streets; the echo of music being played somewhere around the corner by an unseen guitarist. I miss the heady perfume made up of coffee, oranges, tobacco, sewer gas, onions frying in olive oil, diesel fuel, chestnuts smoldering on outdoor braziers, freshly baked bread, the damp mustiness of old churches, and jasmine wafting through an open window.

Most of all, I miss the people. I worry about who will still be there when I’m finally able to go back. Seeing all of the places and faces in this show brought home the reminder that, for now anyway, all of these things are being denied to me and many others. Given his own, intense Hispanophilia, I imagine that William Merritt Chase would be out of his gourd over it.

Still, the exhibition catalog at least provides some visual comfort and contains an excellent, informative overview of some of the issues to consider when reflecting on both the art and the themes in this show. Not all of the essays are of equal value — sometimes a cigar(rera) is just a cigar(rera).

Yet, on the whole, the catalog’s juxtapositions of the many objects in the show alongside others that are not, but are related to them, provide the reader a deeper dive into ideas about how Spain was, and to some extent still is, often perceived by an outsider’s perspective, as well as the often surprising connections between American and Spanish art that arose during an age of dramatically increasing levels of travel and communication.

For those of us longing to go to Spain, while it may not be as good as being there, both this exhibition and the accompanying catalog help us to look forward all the more eagerly to that time when we may finally be able to travel there once again.

COVID permitting, “Americans in Spain: Painting and Travel, 1820-1920” is at the Chrysler Museum of Art now through May 16, 2021, and at the Milwaukee Art Museum from June 11-October 3, 2021.